No matter where in the world disasters strike, the survival of animals can mean the difference between recovery and despair. More than one billion people depend directly on animals for food, jobs, income, transport, social status, cultural identification and financial security.

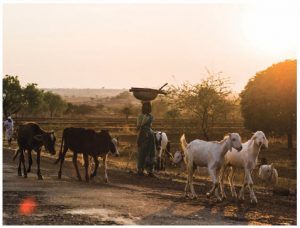

For 70 percent of the world’s poorest people — those most vulnerable to the devastating effects of disasters — livestock are essential for their livelihoods and food security. From the donkeys that carry their water, firewood and most valuable goods to market to the cattle that draw the plows and produce food for the family’s subsistence and income, the survival, health and welfare of these animals is critical. Yet despite their importance, animals are often neglected in disaster planning and response work, due to insufficient knowledge and skills, unassigned responsibility and a lack of funding and policy integration.

Helping animals helps people

The lives of animals and people experiencing disasters are inextricably linked. Many people refuse to flee without their animals; or they risk returning to dangerous disaster zones in order to care for them. The loss of animals in disasters can result in their owners and the local community suffering from malnutrition, food insecurity, debt and dependency on further aid.

The importance of animals and their welfare to the success of humanitarian and development work globally cannot be overstated. Animals are a significant part of the diet in the world’s hungriest nations

and a rich source of micronutrients — particularly important to pregnant and breastfeeding women and those who are immuno-compromised. In the most impoverished countries, as much as 80 percent of people’s cash income is dependent on livestock. And since good animal welfare practices improve the animals’ survival, health, productivity and resilience, they are important for eradicating poverty and hunger.

World Animal Protection

World Animal Protection (formerly known as World Society for the Protection of Animals or WSPA) has been saving animals involved in disasters for 50 years. We are the only non-governmental organisation with full-time trained staff in key locations around the world that can provide an immediate emergency response for animals at a moment’s notice.

This means we have experts on the ground who understand the local context and can build long-term relationships with the community, government and veterinarians so they are better prepared to help animals when the next disaster strikes. Our track record with national governments, the United Nations and humanitarian organisations enables us to work more strategically and effectively to find the best possible solutions for people and animals alike.

Our organisation is there for the full disaster cycle (preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation). We deliver expert emergency response and world-leading risk reduction and preparedness planning and training. By integrating animals into government-led disaster response networks, we aim to protect more animals and the people who depend on them well into the future.

Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013

More than six million animals died when Super Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines last year. We sent our disaster experts from around the world to the poorest and worst-hit areas on the islands of Panay, Leyte and Cebu. Here, local people depend on poultry, pigs and cattle for their livelihoods and food security. Buffalo are also critically important for plowing the land and harvesting the rice fields. Many animals died during the typhoon and food was running out for the survivors. As the district veterinary offices were either completely wiped out or severely disrupted, the community and government welcomed our help.

We partnered with the Philippines’ Bureau of Animal Industries, Department of Agriculture and the University of Aklan to plan the most effective emergency response. Veterinary treatment, emergency feed and mineral supplements saved the lives of more than 17,000 animals. Addressing the immediate needs of the animals is just one part of the disaster cycle. When our short-term response ended, our experts stayed to assist our Philippines-based partners in preparing for future disasters.

As an illustration of the devastation, take Jeniffer Inamarga’s situation. The typhoon destroyed her farm and livelihood. Six hundred of her chickens drowned when the coop was blown into a pond and the pigs died when their shelter was destroyed.

“We thought the world had forgotten about us,” said Ms Inamarga. “We have nothing without our animals.”

We worked with Ms Inamarga and her community to build a model disaster-resistant farm where her chicken coop once stood. With a detachable roof and underground shelters, the new farm is more resilient to disasters. Unlike most farms where the animals are kept in intensive confinement on hard floors, the newly introduced pigs and chickens are free to move and behave naturally on a compostable deep litter floor.

We are monitoring the farm to ensure it is economically viable and that it adequately protects the animals. If the model is successful and replicated, it may prevent the loss of tens of thousands of animals and protect their owners’ livelihoods when the next inevitable disaster strikes.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization recognises that the “loss of livestock not only represents a loss of income for families, but also family savings and investment over many years.” In the Philippines, the loss of a few pigs could mean the loss of your child’s schooling for a year or not being able to get essential hospital treatment.

Improving local veterinary capacity

Our lead veterinarian, Dr. Juan Carlos Murillo, taught veterinary students in the Philippines as he treated sick and injured animals affected by the disaster. When this emergency response work ended, the training continued on mountain bikes. With many roads damaged by the typhoon, alternative modes of travel were needed. We equipped them with light and versatile veterinary kits, each containing enough medicine to treat 100 cattle or 300 pigs. When the inevitable typhoons strike again, more trained veterinarians will be ready and able to get to hard-to-reach areas and take care of the animals.

Recovery in Haiti: Earthquake in 2010

When Haiti was hit by the most powerful earthquake in 200 years, an estimated 3.5 million people were affected and more than one million farm animals and pets died or were injured and abandoned.

World Animal Protection helped create and lead a coalition of organisations to provide immediate relief to more than 50,000 animals in some of the most affected communities. By creating mobile veterinary clinics, we were able to reach the more remote areas and by having local veterinarians run the program, we were building local capacity to respond to future disasters.

The coalition helped rebuild the national veterinary laboratory, which was damaged by the disaster and is critically important for the assessment and surveillance of infections and zoonotic diseases such as anthrax and rabies. The refurbished laboratory has triple the capacity to carry out diagnostic tests to prevent the deaths of tens of thousands of animals and protect more than 500,000 people from infections and diseases.

When power is unreliable or out during a disaster, it can have a significant impact on the success of our work. Important life-saving vaccines would be rendered ineffective if they aren’t stored or transported at the appropriate temperature. To mitigate this risk, we developed 12 solar cold chain units with 100 smaller portable cooler boxes that can be brought to remote locations. [A cold chain is a system of uninterrupted refrigerated storage and delivery units.]

Myanmar: Cyclone Nargis in 2008

The cyclone killed more than 50 percent of the country’s livestock and surviving animals suffered severe injuries, trauma and the after-effects of near drowning. Water contamination and a lack of vet facilities increased the risk of diseases spreading and infecting animals and people.

An estimated 52 percent of arable land in developing countries (28 percent of the world’s arable land) is farmed with the help of 250 million draught animals. Draught power is crucial in Myanmar — a country with only 1,000 tractors. Without cattle and buffalo to draw the plows, local farmers would be unable to plant deep-water rice for the imminent monsoon season.

Our disaster response team immediately prioritised the welfare of the surviving draught animals to help avert a second disaster in the form of severe food shortages and loss of income. We provided concentrated feed and vitamin supplements, treated the animals’ injuries and vaccinated them against seasonal diseases.

The success of this intervention convinced the government of the need to address humanitarian and animal welfare concerns in an integrated disaster plan.

Mitigation in Mexico

Two years of drought (2010-2012) and three successive failed farming seasons had a devastating impact on the people living in the State of Chihuahua who depend on livestock for their food and livelihoods.

Thousands of animals died of exhaustion and starvation as pastures dried up and what grass remained was a longer distance to reach and quickly became overgrazed. This drought affected 70 percent of the animals in regions surrounding Aldama, Ojinaga and San Francisco de Borja.

There was not enough feed for the animals that survived the drought, so many families were forced to sell them at a poor price, losing their main source of income and savings and undermining resilience.

With the help of local groups, we planted indigenous cacti as an emergency food source and built wells and a bore hole to provide water for the animals and to irrigate cactus plots.

Inspired by the sand dams we have seen in Northern Kenya, we advised on the construction of retention ponds to collect rainwater runoff. These simple solutions saved the lives of 2,500 animals and helped ensure long-term food and economic security for 220 families who will be more resilient when the next unfortunate drought occurs. With the University of Coahuila now delivering community training in animal and environmental management in disasters, more people are developing humane and sustainable solutions.

India’s drought (2013) and flooding (2012)

India is prone to natural disasters and whether drought, flooding, avalanches, cyclones or dust storms, the typical result is massive losses to people and the animals they depend on.

Agriculture is important to the economic growth of many nations — particularly India, the world’s largest dairy producer and third largest egg producer.

In Maharashtra, India’s second most populous state, 64 percent of the population makes its living from livestock and agriculture. When the worst drought in 40 years devastated the region, hundreds of thousands of people and animals were at risk of food and water shortages and increasing poverty.

The state government, recognising the importance of cattle and buffalo for food and livelihoods, set up 400 emergency camps to provide the surviving animals with food and water. However, with no place to wallow and no shelter from the hot sun, many animals remained at risk. Since sugar cane was the only food available, they were unable to get the essential minerals they needed to regain strength.

We worked with the government to provide mineral blocks and netting to shade the animals. It may seem like a simple measure, but it sustained the health, welfare and productivity of 9,000 cattle and buffalo. We encouraged the government to adopt this approach in all of the camps across the state to save the lives of 400,000 cattle and the people in the 12,000 villages that depend on them for food and income.

Protecting livestock in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster provides high economic returns as it directly assists the livelihoods and existing productive assets of local people. For example, Economists at Large estimated that our short-term response to flooding in Assam, India, supported $96 worth of livestock production for every dollar spent.

More than 1,000 farm animals drowned and nearly two million were affected by flooding in the seven most severely hit districts of northeastern India in 2012. With much of the grazing land submerged, we quickly deployed a team to provide emergency feed and veterinary care to more than 56,000 animals. This, in turn, helped to protect the livelihoods and food security of more than 4,000 households in Dhemaji. The name of this district means “playground of the floods,” signifying the likelihood of another disaster striking and emphasising the importance of emergency preparedness and risk-reduction planning.

The importance of animals

From the Haitian children who waited in line to take their animals to our mobile vet clinic, to the Pakistani families who used the tents provided to them by aid agencies to house their animals instead of themselves, it is clear that animals matter immensely to some of the most vulnerable people on the planet.

A community’s ability to resist and recover from disasters is closely linked to its animals’ wellbeing. When crops are damaged from a disaster, the community’s cows can still provide milk and the chickens can keep producing eggs that can be consumed year-round, in addition to much-needed manure to restore the crops. Ensuring the animals’ welfare is a good hedge against food scarcity and unpredictability.

When animals are included in emergency planning, policy and response, it not only reduces human and animal suffering, it also facilitates recovery and the achievement of longer-term sustainable development goals. This, in turn, will increase the effectiveness of humanitarian aid.

World Animal Protection has worked with the governments of Australia, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Dubai and Mexico to integrate animal welfare in disaster planning.

Melissa Matlow is the Canadian legislative and public affairs manager for World Animal Protection. Visit worldanimalprotection.ca to find out more.