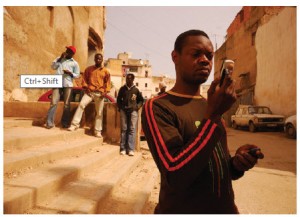

Africa’s latest renaissance is propelled in substantial part by the remarkable indigenous technological transformation of a hand-held computerized gadget — the mundane mobile telephone — into a powerful instrument for human advancement.

Africa pioneered gathering and transmitting merchandizing and market information. More recently, it invented and popularized banking and financial transmission by mobile device. Now people all over the continent receive medical reminders and diagnostic updates through the same medium. In many instances, too, the humble mobile phone is being used to preserve and strengthen democracy. The use of this technology for human advancement is much more innovative in Africa than anywhere else.

Since texting is cheaper than talking, Africans initially used mobile phones to gather information quickly and systematically by a few thumb movements instead of by travelling laboriously and randomly on foot, and then only learning about individual markets. A farmer could obtain the best returns for his agricultural produce or his animals if he knew the current prices for wheat, maize, bananas, millet, cassava, tef, cattle, or goats in near as well as far markets. Texting made that possible. Farmers would not need to travel to those markets until prices were right, and they would always know in which markets to sell their farm products. Productivity and efficiency could thereby be enhanced.

Mobiles for banking

Subsequently, especially in Kenya, where the first breakthroughs occurred, Africans began using their mobile phones to deposit and withdraw savings from special banking accounts. Now they pay bills and receive their wages. They borrow money; they donate to charity through their phones. They pay taxes, too. They invest their savings, trade shares on stock exchanges and transfer large sums locally and internationally to relatives. Sending remittances in that manner avoids large fees. In a part of the globe where very few had standard bank accounts or means of shifting sums to kin or providers, the texting function of mobile phones has now made it much easier for people everywhere, even those living in remote villages, to enter the monetary universe.

Thanks to their numeric keypads, it is easy to see how mobile phones have become financial instruments as well as information accumulators. But what is equally transformative for sub-Saharan Africa, where the dissemination of ideas and knowledge has traditionally been slow and limited, is that the text message capacity of mobile phones has made it possible for governments and officialdom generally to be much more interactive than ever before, producing a more enlightened and responsive citizenry.

A tool of democracy

Even the deaf can now communicate — by text. Likewise, citizens have been able to complain, to exercise their civil rights and — using mobile phone photographic capabilities — to document their reports of official error.

In urban KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa), for example, one angry petitioner used text messages and attached videos finally to persuade a lagging municipality that sewage outflows were inundating his house and small plot. The evidence was irrefutable and a hitherto unresponsive set of bureaucrats acted. In other cases, governments replaced missing street lights and road signs, thanks to proof from mobile phone photographs.

Now people can get licences and permits of all kinds more easily, as well. No longer are bureaucrats behind imposing grilles able to interpret regulations arbitrarily; empowered citizens learn their rights by text and proceed to exercise them, if necessary by documenting abuses.

Africans may soon embrace a startup information-gathering and transmission method from India. There, an enterprising radio reporter and producer realized that large populations lacking literacy and access to reliable sources of national and local information would benefit from receiving news on their mobile phones, by text. His new service supplies the millions in India’s Chhattisgarh State, currently embattled by a Maoist rebellion. Africans will doubtless emulate his innovation,

region by region or country by country.

Reaching out medically

There is a burgeoning medical dimension to the embrace of mobile telephone technology, especially significant in a part of the world that suffers routinely from rampant diseases and a shortage of medical personnel. For instance, whereas Europe boasts 3.6 physicians per 1,000 people, poor places, such as Malawi, count 0.02 physicians per 1,000 and even South Africa’s numbers are no better than 0.77 per 1,000. Thus, whereas North Americans can rapidly run down to an emergency room or a trauma centre, Africans who are ill, or who are carrying a seemingly comatose baby, must trudge miles on foot to a barely staffed clinic.

For those reasons, outgoing and incoming text messaging abilities are a godsend. Women in Ghana regularly receive lactation advice through text messages. Tuberculosis patients are monitored and reminded to take their medicines via text messaging. A flashing light on a smart phone can remind someone to keep an appointment. Rwanda has distributed free mobile phones to thousands of community health workers so they can keep track of pregnant women, send emergency alerts, call ambulances and offer updates on emerging health concerns. In Uganda, “Text to Change,” enables very similar capabilities.

Even more dramatically, in Nigeria, mHealth, a mobile telephone-based application developed by a Nigerian research company, played a very significant role in preventing the spread of Ebola after it was first discovered in Lagos and Port Harcourt. Use of the mHealth app reduced reporting times from 12 hours to six hours, and then almost to zero hours. As Nigerian health workers attempted to trace individuals who had had contact with a person who had arrived from Liberia, they entered tracing details into their phones and transmitted the data derived from nearly 19,000 visits.

UNICEF has launched RapidPro, a free, open-source platform. In Liberia, it helps trace cases of Ebola, reports on new cases, circulates messages about care and prevention and shares training information. It has effectively bolstered co-ordination between the Liberian ministry of health and outreach health workers.

Similarly, in Zambia, U-Report, another UNICEF tool, employs text messages to link patients to the resources of the local national HIV-AIDS council. Since 2012, more than 50,000 young people have, by such anonymous means, been referred to counselling services. Voluntary testing among those who use the U-Report tool has reached 40 percent, nearly double the national average.

M-Pedigree, in Rwanda, Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana, is a drug-monitoring system that permits consumers and health workers to send a text code to a central hotline quickly to verify whether about-to-be-purchased medicine is genuine or counterfeit.

Smart phones are also capable of acting as sensors and diagnostic assistants. Health-care workers are harnessing the computing power of such phones to take blood pressures, monitor blood sugar levels, hear heartbeats, and even (using photography) to peer down throats, look into ears and examine body lesions from afar. No matter how remote the patient, he or she can thus tap into ready-made medical support systems; such do-it-yourself medicine is uploaded to smart phones and sent on to health providers in a distant city.

There are new ways of obtaining almost instantaneous verification of suspicions of malaria. One method uses a slide smeared with blood that is put under a special attachment for mobile phones. A British innovator has designed a mobile-phone- powered surface acoustic wave device to diagnose malaria remotely. Another ingenious researcher in Africa has demonstrated how an otoscope can be fitted to a mobile telephone so that the ears of babies can be investigated and the results read in a distant clinic. In some places, stethoscopes and smart phones have been paired to listen to and assess heart conditions.

Tackling corruption

Text-messaging brings about social change. In some countries, mobile phone reporting by text message has alerted civil society organizations to bribe-taking in real time, rather than days later. Mobile phone photographs have also been available to document the extent of peculation and other corrupt behaviour. Incidents of bribery have been transmitted to the authorities in such a manner that they could not be denied and action could not be avoided. This is not to suggest that corruption can be cured via mobile telephonic surveillance; rather, the existence of corruption can at least be made more visible and middle-class countervailing forces aroused. (In Africa, the growing middle-class is connected to the global village and aware nowadays of how Africa needs to catch up to Asia and Latin America, especially with regard to curbing corruption.)

A number of recent election results (Senegal, Ghana, Kenya and Zimbabwe, among others) have been monitored by various local civil society organizations for accuracy by “quick counts” transmitted to central aggregating stations in capital cities or externally, for fear of local interference. More and more, NGOs are verifying the validity of election returns in this manner, with mobile phones providing the medium and presenting results in real time. Doing so makes it harder for illicit regimes to rig votes or otherwise interfere with outcomes.

Boundless potential

Nothing is so powerful a force for positive change in sub-Saharan Africa as the embrace of mobile phone technology and mobile phones as primary sources of information and human interaction. Fortunately, at least two-thirds of sub-Saharan Africa’s nearly one billion people use mobile phones daily. About the same proportion of persons in sub-Saharan Africa have ready access to mobile coverage — to a signal (even if 2G rather than 3 or 4G).

Originally, the adoption of mobile phones occurred because traditional landlines were few, expensive and hard to access in Africa. But once the potential of mobile telephony was appreciated, it quickly became the medium of choice for all communicators. It had the enormous advantage of requiring few fixed installations; only cell towers were necessary instead of costly copper wires strung from pole to pole and exposed to the natural elements and theft.

A second revolution was the bright decision by early mobile telephone entrepreneurs in Africa to discard traditional billing systems, replacing them with an insertable SIM (subscriber identity module) card that individuals could buy at shops across the continent. With SIM cards available in almost any reasonable amount, even poor Africans were able to buy air time without large investments. The companies were able to avoid costly and worrying accounting systems, and so the new medium proliferated.

The mobile phone is now sufficiently powerful and inexpensive, and coverage across most sub-Saharan African countries sufficiently extensive, that Africans are able to benefit from a means of communication and a mode of sharing that had largely passed the continent by. Every day, mobile phones are used even more creatively than the day before. As “smart” phones become more available and less expensive, so this spread of technology will continue, almost superseding the need for heavy broadband widths. Personal computers are more efficient, but more cumbersome and more expensive to purchase.

Entering the global village

For Africa, what is accessible through the mobile phone truly, for the first time, makes the global village a meaningful concept. Africans understand each other, and the vagaries of the world, in ways not possible before the arrival of mobile phones. These phones also give Africans the means to do more on a daily basis than ever before. Their household productivity has soared, as has their ability to demand more services from hitherto unresponsive governments or local bureaucracies.

Using the letters on the keys, Nigerien teachers have used mobile phones to teach reading and drill basic arithmetical skills. Children as well as adults therefore learn through the mobile telephone. In these and in so many other ways, the mobile telephone has transformed the lives of all Africans for the better. But these transformative endeavours are early signs of what is to come through the full use by more and more Africans of mobile phones. As they harness the capacity for change presented by these devices, what Africans hold in their hands makes their lives better and more enriching.

Robert I. Rotberg is fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center; senior fellow, Centre for International Governance Innovation; fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences; president emeritus, World Peace Foundation; and founding director of Harvard’s Kennedy School program on intrastate conflict.