At the UN General Assembly in September, U.S. President Donald Trump projected an “America First” worldview that American sovereignty and national interests were more important than multilateral international institutions and agreements.

Conversely, Chinese President Xi Jinping has been attempting to increase his country’s involvement in international organizations and multilateral pacts.

Last autumn, CNN geopolitics analyst Fareed Zakaria wrote in The Washington Post that “the Trump administration’s most significant and lasting decisions will be about U.S. policy toward China … whether the 21st Century will be marked by conflict or co-operation between the two most prosperous and powerful countries on the planet.” At present, the U.S. has 24 per cent of the global gross domestic product while China is catching up with 15 per cent — and China is expected to bypass the United States in the coming decades.

What does this international conflict versus co-operation mean for Asia? Will Trump’s unpredictable transactional moves result in serious regional upheavals in Asia in 2019? Will areas of tension result in international flashpoints between the U.S. and China, such as their bilateral trade war or the situations in the Korean Peninsula, the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea?

1. How the world views Donald Trump

In the Pew Research Center’s 2018 Global Confidence Poll, in which it asked 26,000 respondents across 25 countries about global leadership, Trump received a lower rating than Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin. Only 27 per cent gave favourable responses about Trump, but Putin got 30 per cent and Xi got 34 per cent. Perhaps not surprisingly, German Chancellor Angela Merkel received 52 per cent favourable responses and French President Emmanuel Macron got 46 per cent.

While 63 per cent of respondents among all countries preferred the U.S. as the world leader — compared to only 19 per cent who preferred China — 70 per cent of respondents across the 25 countries surveyed said they have no confidence in Trump. It seems they echoed the views of the United Nations General Assembly. When Trump gave his anticipated speech to a packed chamber in September, his boasts about his achievements being “better than any previous U.S. administration’s” prompted open laughter.

2. China-United States trade war grows

At a working dinner on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Buenos Aires last

November, Trump and Xi held face-to-face trade issue discussions. Trump agreed to “freeze” for 90 days hiking U.S. tariffs on $250 billion US in Chinese imports from 10 per cent to 25 per cent on January 1. In response, Xi agreed to “freeze” Chinese retaliatory measures as well as to buy an unspecified but “very substantial” amount of American agricultural, energy, industrial and other products. Both leaders agreed that, if no agreement is reached in 90 days on a variety of trade issues, both parties would raise tariffs to 25 per cent. Xi also agreed to designate the drug fentanyl as a “controlled substance” and that sellers would be “subject to China’s maximum penalty under the law.” This synthetic drug has been linked to the current epidemic of opioid-related deaths in the U.S. — and in Canada as well.

Viewing this bilateral trade war with its growing tariff barriers, Indonesian President Joko Widodo recently likened the world economy to feuding dynasties in the HBO series Game of Thrones. He went on to warn of “global economic dystopia.”

While it is difficult to determine the coming steps in the 2019 U.S.-China trade negotiations, it is useful to outline what took place in 2018. At the first round of bilateral trade talks in May, 2018, U.S. negotiators gave Vice-Premier Liu He a detailed list of more than 140 specific demands to “correct” their bilateral trade and to help reduce the growing American trade deficit with China. This included eliminating Chinese market access barriers and major long-term purchases of American energy and agricultural commodities.

But it is uncertain that such steps will reduce Beijing’s large trade surplus in goods with the United States — and it could impact world trade in some commodities. For example, China — the largest buyer of the 2017 U.S. soybean crop — cut its American soybean imports in retaliation for U.S. tariffs and sales dropped by 94 per cent from the previous year. As a result, Chinese importers switched major orders to Brazilian soybeans. So large were the orders, they cut into soybean supplies for the domestic Brazilian market.

In August, Chinese trade negotiators indicated agreement could be reached on one third of the concessions the U.S. demanded and that they would discuss another third of the list. On the remaining third, they declared these were off limits due to national security or sovereignty concerns. Among them were U.S. demands that China’s domestic cloud computing market be opened to foreign companies.

Some American economists have predicted that the U.S.-China trade war will last more than a year. At a recent South China Morning Post China Conference in Kuala Lumpur, keynote speakers felt that the U.S. efforts to isolate China through trade tariffs were bound to fail because of the world’s closely interconnected national economies.

Perhaps surprisingly, prominent Chinese economists reportedly have begun blaming the “China model” for the trade war with the U.S. and its impact on the Chinese economy — including the drop to 6.5 per cent GDP growth. They argue that China’s state capitalism had sparked backlash from Western industrialized countries, especially the Trump White House with its growing tariff barriers to Chinese imports.

3. Détente between China and Japan

In October, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a landmark state visit to China — the first by a Japanese leader in seven years. Commemorating the 40th anniversary of the China-Japan Peace and Friendship Treaty, this marked a major effort to improve co-operation between the second and third biggest economies in the world. Abe and Xi reportedly signed business accords worth $2.6 billion US. The primary reason underpinning this Sino-Japanese détente is the trade war being waged by Trump and the tariffs slapped on Chinese goods.

But Sino-Japanese security relations continue to be confrontational. Abe has pursued a more assertive Japanese foreign policy accompanied by efforts to strengthen the Japanese Self-Defence Force — which China has denounced. At the same time, he has opposed China’s claims to Japan-held islands in the East China Sea and counselled against China’s man-made islands in the South China Sea. Following his Beijing visit, Abe hosted a summit meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The two regional powers are concerned by the rise of China and its increasing military assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region. Yet they are also concerned by the unpredictable, transactional Trump White House that is confrontational to its allies and competitors alike.

4. China’s BRI leads to debt traps

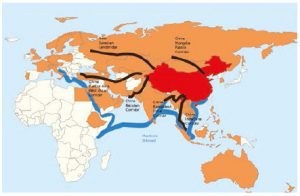

From Central Asia to South Asia; Southeast Asia to Africa; and the Middle East to Central and Western Europe, China under Xi has been provoking the United States by making major investments, offering huge development loans and encouraging Chinese construction companies and financial institutions to pursue megaprojects. Since late 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been exploiting these regions’ need for investment and development — even while leveraging out American influence. This $1-trillion infrastructure investment plan is seen by U.S. defence officials as part of Beijing’s drive to expand its global influence and military power-projection capabilities.

But these megaprojects have led to a number of less-developed countries entering into huge loan obligations and overwhelming debt. This has been the case for at least five countries, including Sri Lanka (loans and port lease), Pakistan (China–Pakistan Economic Corridor project loans), Montenegro (highway loan), the Maldives (bridge and port loan) and Djibouti (port and rail). It has led to these countries being pressured to take on long-term Chinese control leases on ports and basing rights.

Pakistan, which has been China’s landmark BRI infrastructure and trade project, has stirred up considerable controversy. Saddled with its large Chinese loans for megaprojects, the country has seen its foreign currency reserves continue to dwindle to such an extent that newly elected Prime Minister Imran Khan has sought debt relief from Saudi Arabia and an International Monetary Fund bailout. He seems likely to even seek debt relief from China itself to weather Pakistan’s ongoing financial problems.

In Malaysia, its new prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, cancelled four BRI-funded megaprojects, thereby reducing the country’s loan debt by more than US$72 billion. This included BRI loans for the East Coast Rail Line (ECRL), the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail and the Trans-Sabah Gas Pipeline projects. According to Mohamad, these mega infrastructure projects incurred huge debts without considering the government’s ability to repay them, “giving problems to the people.” And, in the case of the ECRL project, the funds had been “borrowed on the condition that a foreign [Chinese] company would be given the contract.

5. Rising concerns about AIIB funding

A number of BRI projects have been funded by loans from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which is based in Beijing. This new multilateral financial institution was founded in December 2015 to fund regional infrastructure development, but some see it as a tool for regional economic integration and a foreign policy instrument for China’s Communist leadership. China holds more than 26 per cent voting rights — compared to just one per cent voting rights for Canada, while 52 other member states have even less — in the AIIB for determining approval for foreign project loans.

Apparently in response to growing criticisms of massive infrastructure financing increasing debt loads of developing countries in an unsustainable way, AIIB president Jin Liqun recently stated that “infrastructure projects funding by the [AIIB] must not add to the receiving country’s debt burden.” He went on to say that the AIIB should “work with the private sector companies in those countries so that our investments would not build up heavy pressure on their debt burden.”

Interestingly, in a sharp reversal of its foreign-aid approach, the Trump administration in October signed into law legislation to underwrite $60 billion US in loans, loan guarantees and insurance to companies prepared to do business in Africa, Asia and the Americas. While at a substantially lower level than China’s $1-trillion US BRI program, it has been seen as an attempt to counter China’s infrastructure investments in those regions.

6. Taiwan Strait: More cyber-attacks

Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is traditionally independence-leaning, but President Tsai Ing-wen has said she wants to maintain the status quo with China. Alternatively, China’s Xi has continued to apply political, economic, diplomatic and military pressure on the island. As he has said previously, the issue of Taiwan being brought under Beijing’s control cannot be postponed indefinitely; and some analysts believe he is determined to do this during his time in office. In addition, there have been more cyber-attacks across the Taiwan Strait.

Currently, Taiwan is braced for an increased onslaught of disruptive cyber-attacks from mainland China — both ahead of the nationwide local-level elections and into 2019, Howard Jyan, director- general of Taiwan’s cyber-security department, told Bloomberg News. He stated that the Taiwanese government endured 360 successful cyber-attacks in 2017 after tens of millions of cross-strait attempts, possibly compromising sensitive and classified data. There are also fears there will be increasing social-media interference as national elections approach in January 2020.

7. Evolving Asian economic integration

In addition to Japan and China attempting to improve their economic relations, several multilateral economic groupings are pursuing free trade and energy relations in the Asian region. Although Trump took the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) by executive order in January 2017, the remaining 11 member countries, led by Japan and Canada, agreed on a replacement trade pact called the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

This trade and regulatory agreement can come into force 60 days after six signature countries pass enacting legislation. Mexico ratified the pact in June 2018, Japan in June, Singapore in September and Canada, New Zealand and Australia in October — with Vietnam and Chile poised to ratify at press time. With the Australian ratification, the CPTPP was to come into force in December, giving momentum to liberalized trade amid global tariff wars. But the implementation of lowered or eliminated tariff barriers in various economic sectors will be phased in over 2019 and later years.

Although it has not been a party to the original agreement or the new CPTPP, the Chinese government has hinted that it might be interested in participating in the agreement in the years ahead — if only as a way to bypass American economic pressure. Meanwhile, a specific clause in the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) provides Washington with a near-veto over any attempt by Canada or Mexico to reach a free-trade deal with a “non-market economy.” The clause is widely thought to refer to trade pacts with China.

And even Trump has publicly voiced the possibility that the United States might reconsider membership in the new CPTPP “on more favourable [America First] terms” — even as he seeks more favourable bilateral trade deals with several CPTPP members in an effort to contain China’s regional ambitions.

The 16-country Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — currently under negotiation — would, if concluded, be the world’s largest free-trade deal. Though negotiations on seven of the 16 chapters of the agreement are complete, the Economic Times of India has suggested that the “heart of the negotiation will only begin next year [2019].” The ASEAN countries and their key partners had been seeking to conclude this region-wide pact by year-end 2018, but little is now expected to be concluded until after mid-2019 as several countries — including Indonesia, the Philippines, India, Japan, Australia and New Zealand — are going for national elections. The RCEP agreement is to maintain the free trade and rules-based multilateral trading system that has underpinned the region’s economic growth. The RCEP group comprises the 10 ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia, Brunei and Laos) plus India, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

In addition, at the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF), in the Russian city of Vladivostok, Russia, Mongolia, China, Japan and South Korea signed a series of hydrocarbon production and supply agreements designed to accelerate development of regional energy supply infrastructure in Northeast Asia. To support this regional development, Mongolian President Khaltmaa Battulga proposed, as part of his country’s “Economic Corridor” strategic policy, that Russia build a natural gas pipeline to China via Mongolia as well as an “Asian Super Grid” to help balance the regional electricity peak load. Reports say Xi and Putin have voiced support for pipelines through Mongolia pending feasibility studies.

8. Possible second Trump-Kim summit

At the East Asia Summit in Singapore last November, U.S. Vice-President Mike Pence said the Trump White House was planning a second summit in 2019 between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un — but no summit date or location had been confirmed.

In June 2018, Trump held an unprecedented summit with Kim in Singapore and signed a vaguely-worded statement on denuclearization for the Korean peninsula. A follow-on summit will again aim to persuade the North Korean regime to abandon its nuclear weapons program.

Despite four visits by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to Pyongyang and the cancellation of the third major joint American-South Korean military exercise, there have been no breakthroughs on the slow-moving denuclearization talks with the North Korean regime. The Americans want an inventory of its nuclear weapons systems and facilities. It has still not given a firm commitment to irreversible steps to its nuclear disarmament or even an inventory of its nuclear weaponry. In addition, it still has its chemical and biological weapons stores — and armed forces with one million personnel.

The North Korean regime has been demanding an easing of the international sanctions and a declaration of the end of the Korean War (which stopped based on truce agreement in 1953). It also wants the U.S. to take “reliable corresponding measures to guarantee the security of the [North Korean] regime” in step-by-step progress on denuclearization.

Following three summit meetings with Kim, South Korean President Moon Jae-in stated in an interview with French newspaper Le Figaro that “this year [2018], I have discussed in depth with Kim for hours. These meetings have convinced me that he has taken the strategic decision to abandon his nuclear weapons.” As a result, North Korea and South Korea have begun reducing security tensions on the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing their territories, including reducing security posts and conducting mine-removal in the DMZ.

North Korea is receiving increasingly warm responses to its communist regime. Mongolia has invited Kim to visit its capital of Ulaanbaatar, which had earlier been offered for the first Trump-Kim summit — and possibly could host the second summit, if and when it takes place. Kim has also been invited for a state visit to Moscow, and surprisingly, there are reports that Kim will send Pope Francis a formal invitation to visit Pyongyang.

In October, Russia, China and North Korea released a joint statement insisting that all issues relating to Korea be solved in a peaceful, political and diplomatic way. This supported the North Korean demand for a “step-by-step” approach, lengthening the process of denuclearization, if it ever occurs. As diplomatic and security dialogue between the two Koreas has reduced tensions, there have been suggestions that China, the United States, Japan and Russia should work to launch a “Northeast Asian Security Forum.”

9. More naval tensions in the Indo-Pacific

In early October 2018, there was a near collision between the U.S. Navy guided-missile destroyer USS Decatur and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy destroyer CNS Lanzhou. The Chinese vessel approached from the rear and then cut across the U.S. naval ship’s bow at a distance of 45 metres. The USS Decatur was conducting one of a series of “freedom of navigation” aerial and sea operations that American ships have done near China’s fortified manmade islands in the South China Sea. China has pursued a massive island-building effort to establish military outposts on reefs and islets in the Spratly Islands, including airstrips and missile launch sites. This is to support its claims over most of the South China Sea — the “Nine-Dash Map” — even though the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in July 2016 disallowed China’s “sovereignty” claim.

In April 2018, Admiral Philip Davidson, the new head of U.S. Pacific Command, told his U.S. Senate confirmation hearing that “China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States.” Also in July and again in October, pairs of U.S. destroyers transited the international waters of the Taiwan Strait “in accordance with international law” – in response the Chinese government protested that such sail pasts were provocative. And there have been reports that Trump administration policymakers in Washington are considering sending an American aircraft carrier through the strait sometime in the future.

In addition, the Australian Navy has also conducted sail-past cruises in the South China Sea and through the Taiwan Strait. Similarly, the British Royal Navy is planning cruises through the South China Sea to “showcase support for its Pacific allies” — possibly even including its new HMS Elizabeth aircraft carrier.

10. China may join a new INF Treaty

In 1987, U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev signed the intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) treaty to eliminate all land-launched missiles and cruise missiles with a range between 500 and 1,000 kilometres. In October 2018, Trump announced that his administration planned to withdraw from the treaty in the coming year. While the arms-control agreement has been highly successful in eliminating an entire class of nuclear weapons, in recent years the U.S. and Russia have each accused the other of treaty violations. Trump has suggested the U.S. will have to develop new land-launched INF weapons unless Russia and China commit to stopping their development process.

It was reported that Trump and Putin would likely meet to discuss the INF Treaty in November — either when they both visited Paris or attended the G20 summit in Buenos Aires later that month — but, in fact, for various reasons, no sit-down meeting took place.

Nevertheless, Trump had earlier extended an invitation to Putin to visit Washington in 2018. But the unprovoked Russian military attack and capture of three Ukrainian naval vessels at the mouth of the Kerch Strait between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov placed any visit by Putin on hold. According to senior Putin aide Yury Ushakov on Rossiya 1 TV channel after the G20 summit, Putin and Trump may meet in June 2019 at the next G20 summit in Japan, but “it’s vital for Moscow and Washington to find a chance to hold these crucial talks earlier.”

The main issue for negotiation will be the end, continuation or adjustment of the treaty’s terms, but a key side issue will be China. At present, China is not a signatory to the INF treaty and, as a result, it is free to develop and deploy intermediate-range missiles from the Chinese mainland. This is one of its primary weapons systems for deterring U.S. naval forces operating in the Western Pacific and South China Sea. The new strategic weapons systems of the PLA Rocket Force — formerly the Second Artillery Corps — have the range and accuracy to attack hardened targets, such as airfields and command and control centres in the Asia-Pacific region. This includes targeting American military bases in Japan and South Korea.

In a recent press conference, Trump insisted that China “should be included in a new [INF] agreement.” But the Chinese foreign ministry countered that “it’s completely wrong to link the U.S. withdrawal from the [INF] treaty to China” This is likely because being a signatory to a future trilateral INF agreement would restrict China’s regional military options.

But the U.S. withdrawal from restrictions on INF weapons systems could begin a new arms race with Russia and China. While an American withdrawal from the treaty would signal a return to nuclear brinkmanship, a trilateral INF treaty between the United States, Russia and China could herald a new era of global nuclear peace and détente. However, it would also be necessary to ensure the compliance of North Korea with its nuclear-capable missiles.

Asia needs to closely monitor Trump

In the U.S. midterm elections, the Democrats gained majority control over the House of Representatives, but the Republicans held on to a slim majority in the Senate. This means international agreements that Trump negotiated or forced upon foreign governments — allies or competitors — still need approval from the Senate when the new Congress begins in January 2019. Any future U.S.-China trade agreement or a renegotiated U.S.-Japan economic agreement or a possible renewed interest by the Trump administration to join in the new CPTPP will require this approval. And this will be in the face of warnings of a potential economic crash as early as 2020, due to Trump’s tariffs and China’s counter-tariff disruptions in world trade, in addition to growing national debt levels in the U.S. and China. But there are no indications that such a future crash would be at the same level as the 2008 global economic crash.

In a recent Nikkei Asian Review article, Minxin Pei wrote that, “if Trumpism [America First] dictates that the U.S. must get better terms than its partners under all circumstances, then fewer allies may sign on, making it harder to isolate China.” In any case, the American allies and competitors in Asia will need to closely monitor Trump’s worldview for his transactional policies, tweets and statements, to keep from being caught off-guard and wrong-footed in 2019 and beyond.

A recent New York Times investigation reported that Trump has continued to use one of his unsecured iPhones to call old friends and outside advisers. American intelligence officials have warned that foreign intelligence agencies, especially Chinese and Russian, could be listening in on his personal conversations.

Dr. Robert D’A. Henderson currently does international assessments and international elections monitoring. Previously, he taught international relations at universities in Canada and overseas.