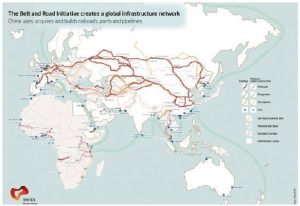

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has several purposes for the emerging superpower: To increase its access to global trade, international development and strategic investment, to up its diplomatic engagement, to isolate Taiwan by buying away the few international friends it has left and to build a constellation of military bases and presence around the world to help Beijing enforce its will on global security.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative has been held out as a modern-day “Chinese Marshall Plan,” spreading economic assistance and technical expertise around the globe to developing economies. Others have been less polite and describe it as thinly disguised imperialism preying on the world’s most desperate and ailing states, where investments in trade and supporting transport hub infrastructure come with strings attached, huge debt and Chinese monopolies. President Xi Jinping’s five-year-old Belt and Road Initiative is reportedly China’s plan for global economic engagement and dominance linking Asia, Africa and Europe. From Southeast Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa, the program includes 71 countries that account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP. Its price tag will likely top US$1 trillion. Chinese firms are engaged in construction work around the world, having secured more than $340 billion in construction contracts along the Belt and Road.

Thus not all is sunshine and lollipops.Chinese investment tends to come at a heavy cost, geared to entrap desperate developing states. Developing economies with massive debt loads that they cannot repay end up having to hand over their best infrastructure — such as dual-use ports, those that can handle civilian commerce and military shipping, and airports — to Chinese monopolies for control and management. Chinese companies and their workers are brought in to construct and develop the sites at the expense of local businesses and workers.

Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Malaysia, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Tajikistan have found themselves heavily indebted to Chinese interests. For instance, in 2011, Beijing wrote off an undisclosed debt owed by Tajikistan in exchange for 1,158 square kilometres of disputed territory.

The Washington Post recently identified an outpost in eastern Tajikistan, near the strategic junction of the Wakhan Corridor, as host to Chinese troops. Sri Lanka was pressured into selling control of its port of Hambantota to a Chinese state-owned company after falling behind on its payments on $1.5 billion to Beijing. Some international security analysts have worried that the expanded Chinese commercial presence around the world will eventually lead to expanded military presence using ports and other transport infrastructure being built for dual-use commercial and military purposes.

People’s Liberation Army (Navy)

There was a time in the not-so-distant past that China’s People’s Liberation Army (Navy) was viewed purely as a coastal defence force, but it is now a “blue water” navy with 300 warships. It is larger than the United States fleet and it sails round the world. Beijing’s 235,000-person navy boasts one aircraft carrier, four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, five hunter-killer nuclear-powered submarines, 61 conventional patrol submarines, 17 destroyers and 54 frigates. At an astounding rate, China commissions between 14 and 18 new warships of various design per year. Today, Chinese warships routinely patrol the South China Sea, East China Sea, Pacific and Indian Oceans, and its anti-piracy action groups have remained in the Red Sea off Yemen since their inception in 2009. Chinese surface ships have travelled to places as far afield as Bulgaria, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Australia, Tanzania, Nigeria, Greece, London, Russia and Lithuania. Transit routes have included the Suez Canal, the Cape of Good Hope, the Bosporus, the Panama Canal, the straits of Magellan, Malacca, and Sunda.

China is routinely operating surface action groups and submarine operations with nuclear and diesel submarines in the Indian Ocean and regularly carrying out joint war games with Russia. Beijing now has one operational aircraft carrier, another undergoing sea trials and one under construction.

China’s ballistic missiles-carrying nuclear submarines have gone on combat patrols for deterrence purposes since 2010. To maintain this relatively new and modern navy around the globe, Beijing is going to need more than a fleet of support ships. It is going to require a constellation of sea and air bases. That’s where the maritime portion of the Belt Road Initiative serves as a cover. China’s new defence white paper, National Defence in a New Era suggests that the protection of China’s global interests is a key strategic objective for the People’s Liberation Army. The white paper contends that “one of the missions of China’s armed forces is to effectively protect the security and legitimate rights and interests of overseas Chinese people, organizations and institutions.” To advance what can only be described as a global strategic agenda, Beijing is developing and deploying “far seas forces,” “overseas logistical facilities,” and capabilities for “diversified military tasks.” The document cites China’s new Logistics Support Base in Djibouti, set up in 2017, as a huge success, confirming the covert military component of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Strategic dual-use sea ports

Clearly, Beijing’s strategy is to develop a global footprint of strategic bases to rival the United States. These bases are a clear attempt to challenge the U.S.’s superpower status and the current international strategic order. China is now the top port operator in the world. By 2015, two thirds of the world’s top 50 container ports had some substantial Chinese investment. According to Lloyd’s List Intelligence, those 50 ports handled 67 per cent of global container volume and if only containers directly handled by Chinese port operators are measured, the level of dominance is 39 per cent of all volumes, almost double the U.S., the second largest nation group .

Chinese commercial shipping fleets are the biggest in the world, with the 5 biggest Chinese carriers controlling 18 per cent of all container shipping handled by the world’s top 20 companies in 2015, higher than any other country. Chinese companies such as China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (COSCO) and China Merchants Port Holdings have acquired shares or signed deals to build terminals at seaports around the world. China has created an entirely state-owned-and-operated global shipping empire with China Merchants and COSCO running 29 ports in 15 countries and 47 terminals in 13 countries. COSCO took over operations at the container port in Piraeus, Greece, in 2008, when the Greek government was near bankruptcy. In 2017, China already had international port holdings with terminals in Greece, Myanmar, Israel, Djibouti, Morocco, Spain, Italy, Belgium, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Brazil, Sri Lanka and Lithuania. China has also made moves to invest in infrastructure and take up ownership of smaller ports, including strategic locations such as Djibouti, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Darwin in Australia, Maday Island in Myanmar and proposed ports on the Atlantic Ocean islands of São Tomé and Príncipe and in Walvis Bay in Namibia.

China’s only overseas base

Currently, China has just one overt overseas military base in Djibouti, but it is widely believed to be planning others, including in Pakistan, as China develops into a superpower. According to the China Daily, the base at Djibouti will reportedly help China ferry aid and peacekeeping personnel to other parts of the African continent, but it will also strengthen joint military exercises and maintain “security of international strategic waterways.” The Pentagon’s annual report on Chinese military power has warned that “China’s advancement of projects such as the ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative (OBOR) will probably drive military overseas basing through a perceived need to provide security for OBOR projects.”

Djibouti is considered China’s first overseas military base and can accommodate almost any ship in the Chinese navy. Satellite imagery and reports show the strategically located logistics base has military infrastructure, including barracks and storage and maintenance units and houses about 10,000 personnel. Djibouti is situated at the Bab-el Mandeb Strait, which separates the Gulf of Aden from the Red Sea and guards the approaches to the Suez Canal through which 40 per cent of Chinese imports have travelled since 2008. China was the seventh country to set up shop in the poor African state in addition to the United States, Japan, France and others. China also made massive investments in Djibouti’s civilian infrastructure projects including a new container port, two new airports and the Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway. Including its new naval base, China currently controls two of the five terminals at the Port of Djibouti.

It seems unlikely that Djibouti will be alone in China’s pursuit of overseas military support hubs. It is believed that the People’s Liberation Army has targeted dual-use ports for military support activities in Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, the Western Pacific, Africa, and even the Americas. According to reports in the Chinese media, Beijing has plans for 18 naval bases that will be established across the Indian Ocean and Africa, including Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Djibouti, Yemen, Oman, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Seychelles and Madagascar. Other potential naval bases reportedly include Chongjin Port, North Korea; Moresby Port, Papua New Guinea; Sihanoukville Port, Cambodia; Koh Lanta Port, Thailand; Sittwe Port, Myanmar; Dhaka Port, Bangladesh; Gwadar Port, Pakistan; Hambantota Port, Sri Lanka; Maldives; Seychelles; Djibouti Port, Djibouti; Lagos Port, Nigeria; Mombasa Port; Kenya; Dar es Salaam Port, Tanzania; and Luanda Port, Angola. In fact, as soon as China took control of large dual-use ports in Sri Lanka, Greece and Djibouti, warship visits by the People’s Liberation Army (Navy) started to become the norm.

The militarization of the South China Sea

Closer to home, China has fortified a bastion of island bases in the contested Spratly Island chain to control the world’s busiest sea lanes in the South China Sea. The South China Sea running north from the Straits of Malacca to the southern tip of Japan is the busiest seaway in the world. The South China Sea is home to a series of maritime border disputes between China and most of its neighbours, including Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Brunei and Malaysia. These sea lanes feed China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and others through which an estimated $5.3 trillion in ship-borne trade transits each year, or one third of the global total of trade. As much as 80 per cent of China’s oil imports arrive through the Strait of Malacca and then sail across the South China Sea to reach China. China has fortified and garrisoned Hughes, Gavin, Fiery Cross, Subi, Mischief, Johnson and Cuarteron reefs with defensive weapons, potentially offensive weapons, air defence sensors, communications, military-capable runways and port facilities to threaten and control South China Sea shipping lanes. This fortified bastion also potentially shelters the Chinese fleet from American intervention in a war over Taiwan while at the same time aiding China in reaching far out in the Pacific to target American warships and bases.

China’s advance on the Pacific

Papua New Guinea has requested that China refinance its debts of $7.95 billion or about 32.8 per cent of its GDP, potentially giving China access to the facilities at Port Moresby. China has also shown interest in the Pacific in terms of a Second World War American base in Asau, Samoa, which has an old runway and a 1960s-era concrete wharf in a well-protected natural harbour. China has also shown an interest in Tonga and servicing its considerable debt of $108 million through China’s Export-Import bank. This would be equivalent to about 25 per cent of GDP in return for concessions. The South Pacific island would make a great base for China’s navy, with its fisheries, seabed minerals and natural resources and it would further isolate Taiwan by taking away the few remaining countries that recognize Taiwan instead of China.

China has also promised to fund the Solomon Islands’ financial needs and required them to break diplomatic relations with Taiwan, which they did very recently. China has even tried to tap U.S. interests in the Marshall and Marianas island chains to sow dissent and weaken Taiwan’s and the United States’ presence in Asia. Sadly, a very recent deal included leasing all 200 hectares of Tulagi Island, a province of the Solomon Islands, as a potential naval anchorage, as well as its surrounding islands, to a Chinese public safety entity. But the provincial government’s lease agreement was overturned by the attorney-general from the central government of Solomon Islands. With a Chinese naval presence in these islands far out into the South Pacific Ocean, China could threaten and put pressure on Australia and New Zealand.

What about the Indian Ocean?

Recently, on the edge of the Indian Ocean region, Cambodia turned down U.S. offers of assistance to upgrade its Ream Naval Base. Cambodia probably did this in favour of an offer from China. Additionally, there are fears that $3.8 billion in Chinese investment in the Dara Sakor resort area that comprises 20 per cent of Cambodia’s coastline, will be turned into a giant Chinese naval and air base facility. The resort will reportedly feature a deep-water port, a large industrial park, resort areas to host tourists, an international airport, power stations, water treatment facilities and a hospital. Recent satellite imagery shows an airport runway in Cambodia’s Koh Kong province with a length similar to those built on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea — it is long enough to support Chinese reconnaissance, fighter and bomber aircraft.

Additionally, Chinese naval forces routinely visit and get support at Sihanoukville Port, Cambodia; Koh Lanta Port, Thailand; Sittwe Port, Myanmar; and Dhaka Port, Bangladesh. These ports give China easy access to the strategic naval chokepoint of the Strait of Malacca. A total of 94,000 ships pass through the straits per year, carrying 24 per cent of the world’s goods, including oil to East Asia. Pakistan’s Arabian super port of Gwadar is strategically located along sea lanes that carry most of China’s oil imports to protect the world’s second largest economy. The port is owned, financed and was built by China and now sees an increase in both Chinese commercial and military shipping.

The Maldives in the Indian Ocean are spread over nearly 1,200 islands, spanning more than 90,000 square kilometres, covering key shipping lanes where China and India are in strategic competition. Beijing lent the government of former Maldives strongman, president Abdulla Yameen, hundreds of millions of dollars for infrastructure projects, such as the new “China-Maldives Friendship Bridge” from the airport to the capital, Malé. Similarly, India had plans to develop facilities in the Seychelles Assumption Island in 2015, to include maritime surveillance and search and rescue, and to renovate an airstrip in the island, upgrade its jetty and construct housing facilities for the Seychelles Coast Guard. India was suddenly sidelined by China, which had similar interests in Assumption Island.

Ambitions in Africa

Chinese entities financed 27 of the 46 sub-Saharan African ports, they operate 75 per cent of these ports, and constructed or reconstructed 90 per cent of them. In addition to Beijing’s naval base and container ports in Djibouti, Chinese naval ships regularly visit Mombasa Port, Kenya; Dar es Salaam Port, Tanzania; and Luanda Port, Angola. China also built a huge $400-million dual-use container terminal in Walvis Bay, Namibia, comprising 40 hectares of land reclaimed from the sea by China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd. in fewer than five years. As previously mentioned, Beijing is also lengthening the main airport’s runway and building a dual-use deep-water port in São Tomé and Príncipe off Africa’s Atlantic Coast. Both are reported to be future People’s Liberation Army (Navy) bases on the Atlantic, where China has never had a military presence before.

Towards the Atlantic Ocean

The United States abandoned its Cold War-era presence at the Portuguese Lajes Air Base in the Azores and, not surprisingly, China has shown an interest in taking over this 3,000-person facility for its own purposes. Further to that goal, China and Portugal, a NATO member state, have agreed to set up a satellite launch space in the port in the Azores and a lab in Portugal to build satellites. To Denmark’s concern, Beijing, in addition to U.S. President Donald Trump, has expressed an interest in Greenland, including proposals to establish a research station and satellite ground station, renovate airports and expand mining. There are reports that China would like to encourage Greenland independence from Denmark as a means of getting a foothold in the Arctic region and access to Arctic oil and minerals. China has also shown an interest in taking on facilities in Iceland, including the United States Air Force base, no matter how unlikely.

The Americas are not immune

Even the United States’ backyard is not immune to Chinese influence and basing rights. China Landbridge, a privatly owned Chinese company based in the Chinese port of Rizhao, bought Panama’s largest port, Panama Colón Container Port (PCCP) at Margarita Island, on the Atlantic entrance of the Panama Canal in May 2016 at a cost of $1.1 billion. PCCP will capitalize on the doubling of the capacity of the canal, which can handle the New Panamax container ships that can transport up to 14,500 25-foot equivalent units. The Panama Canal itself has been under Chinese management by Hutchinson Whampao since 1997 and remains a potential naval chokepoint for ships moving between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. China currently operates ports at either end of the Panama Canal, bridging Atlantic and Pacific and may even convert the old American base in the Canal Zone into a third.

As well, a Hong Kong-based company has a 50-year concession to build a canal through Nicaragua to link the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Dominican Republic has negotiated a US$600-million loan to upgrade power distribution with the China Export-Import Bank, involving the construction of a mega-port and power installations in Manzanillo, on the north coast of the country. China has offered a plan for development of Grenada that includes a deep-water container and cruise ship port and modernizing and lengthening the country’s main airport runway. Beijing has reportedly taken over, or is sharing with the Russians, the former Soviet-era listening post at Lourdes, Cuba, which it uses to spy on the United States. In the aftermath of the recent Hurricane Dorian, China offered to rebuild Bahamas’ container port facility. COSCO is funding improved rail connections between Bolivia and Peru, so mineral production from Bolivia can then be exported to China through Peruvian ports. China’s COSCO purchased a 60-per-cent controlling stake in the Chancay Terminal in the North of Lima for US$225 million. In Chile, China is providing an underwater, fibre-optic network linking the two countries together in the first underwater fibre-optic cable to directly connect Asia with Latin America. As well, in an even more brazen act, the Chinese military has built a space mission control station in Bajada del Agrio, Argentina.

Even Canada, the U.S.’s closest ally and neighbour, is not immune to China’s charm and pressure. Late last year, the Canadian Coast Guard succeeded in positioning four Chinese-built-and-monitored sensors in waters just 300 kilometres off the United States’ Pacific coast on the Endeavour stretch of the Juan de Fuca Ridge as part of Ocean Network Canada (ONC), a grid of marine observatories stretching from the northeast Pacific to the Arctic. The network is monitored by the University of Victoria in British Columbia and the four new sensors are monitored by China’s Sanya Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering (IDSSE), a grouping of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The ONC also has a defence contract to help the Canadian Armed Forces monitor its Arctic waters with the help of an artificial intelligence-based surveillance system. The Strait of Juan de Fuca sits across from the U.S. naval base at Kitsap that has a nuclear submarine shipyard for both ballistic missile and attack submarines and is the only dry dock on the U.S. West Coast capable of accommodating a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier. The sensors are also relatively close to Canada’s Pacific naval anchorage at Esquimalt, on British Columbia’s Vancouver Island. While there is no evidence to suggest the Chinese sensors can be used to track submarines or other warships, suspicions remain. At the very least, the new sensors give China a better understanding of the strategic waterway close to the U. S., and a look into the structure and operation of one of the world’s largest and most advanced underwater observatories.

The plan is multipronged, but clear

Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative is many things: It is a tool for global engagement and the enhancement of trade, it is a program geared to “soft power” diplomacy in showing off China’s financial, economic and technological success. But the Belt and Road Initiative has an imperialist dimension to it, playing on the most desperate of developing countries that require massive amounts of infrastructure and investment and will make any deal to get them, even at the expense of their sovereignty. The hard economic power, potentially coercive in nature, that China can deploy around the world helps it succeed in isolating enemies, such as Taiwan, from its friends, but also such strategic competitors as the United States and India in terms of their plans for military basing rights. As is the case with Djibouti, the Belt and Road Initiative and the Chinese overseas investments and interests that it represents are under the protection of the People’s Liberation Army as laid out in President Xi’s new defence white paper. The Belt and Road Initiative, either through engagement or investment and construction, is a potential intelligence boon to the People’s Republic, particularly in the infrastructure around critical economic, transportation and communications hubs.

To be fair, it depends on what side of the hill you are looking as to what the main advantage or strategic objective of the initiative is, but a clear byproduct is to develop a constellation of military bases around the world to protect Chinese interests and investments. Chinese naval power, at 300 warships and growing, is the most flexible tool for protecting and advancing Chinese interests without leading to a bloody conflict and even the Americas need to be prepared for the visiting naval squadron or surface action group in a dual-use port bought, paid for, constructed and operated by China.

The sequence of events has been clear: first the Belt and Road Initiative and money for infrastructure as either a loan or gift, then the debt trap, followed by the arrival of the Chinese navy. Then the military presence becomes permanent. Looking at potential ports and military bases is like looking at a “chess board” and this article has touched on only a few. There are many options to grab or acquire dual-use port facilities in a world dependent upon maritime trade and not all are value-maximizing, but they are available to an emerging superpower for a price. The People’s Liberation Army (Navy) is a keen student of the naval strategy of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1660-1783), first translated into Chinese in 1954 — particularly of Mahan’s belief in the great decisive sea battle. China has also taken lessons from the great British naval historian and strategist, Sir Julian Corbett, in his Some Principles of Maritime Strategy and understands that what happens on land influences what happens at sea, and knows the value of overseas bases and what they bring to the table if intervention, conquest, and victory are requirements of the day.

Joe Varner is the former director of policy to former defence and justice minister Peter MacKay. He is author of Canada’s Asia-Pacific Security Dilemma and a fellow of the Conference of Defence Associations Institute and Inter-University Seminar on Armed Forces and Society.