As we begin to observe the bicentenary of the War of 1812, it’s hard to miss the importance of a passage on the very first page (the first of 958) in Amanda Foreman’s impressive new book A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War (Random House of Canada, $40). One legacy of that war, she writes, summarizing the political and diplomatic mood of London in the decade before the Civil War, was the fear that the United States would invade Canada (for a third time). The anxiety was partly in response to “a conviction among Americans that they should never stop trying” to do just that. But there was a second factor as well. Forty years had passed but it “was neither forgiven nor forgotten in England that precious ships and men had had to be diverted from the desperate war against Napoleon Bonaparte in order to defend Canada.”

Dr. Foreman, an English-reared resident of New York, educated at Sarah Lawrence College and Oxford, has written a masterful and exciting one-volume history of the Civil War itself, with all its gore and (a popular Civil War concept) glory. Yet she’s done far more than that. She focuses on how old-fashioned diplomacy prevented what could have been a world war of sorts, as the British Empire took up one quarter of the global land mass. The heart of the matter was the familiar possibility that the Northern government would annex Canada, as the U.S. secretary of state, William H. Seward, kept insisting it do. That would have had the effect of bringing Britain into the war as a Southern ally. The cooler head of Abraham Lincoln sought nothing of the kind, famously saying “One war at a time.” The British too had no wish for such an outcome. The situation, however, came to a boiling point several times, thanks to the intrigues of Confederate diplomats in Canada, Britain and France.

In Canada, there were Confederate representatives posted to Halifax, Montreal and Toronto. They were mere “commissioners” because the South wasn’t recognized by any other country and so had no embassies or ambassadors. These Canadian commissioners didn’t work together terribly well (one reason being that they didn’t all report to the same branch of the Confederate government in Richmond). Even individually they were not quite successful, despite having a secret fund of a million dollars in gold: a tremendous amount of money for a government that, throughout the war, had difficulty even keeping its soldiers clothed and shod.

The commissioners’ plans to encourage anti-war sentiment in the North and execute a series of clandestine raids into U.S. territory were generally unworkable, though one venture — a raid on the town of St. Albans, Vermont — was successful enough that it didn’t end in ludicrous failure. The success rate, however, didn’t matter so much as the fact that such events took place at all. By permitting them to proceed, Britain seemed to have assumed an ambiguous if not downright passive attitude to its own neutrality laws. Many British and British colonial subjects living in the Northern states got caught up in various drafts while the towns along the U.S.-Canada border were full of official recruiters, as well as “crimpers” who impressed innocent fellows into service in a kind of low-grade kidnapping. And of course individuals of many other nationalities rushed to America to join the one army or the other.

The United States and Britain came closest to declaring war on each other in the first year of the conflict. In November 1861, an American warship, the San Jacinto, commanded by Charles Wilkes, stopped a British mail packet, the Trent, in international waters off the Bahamas and abducted the Confederate commissioners to London (James M. Mason) and Paris (John Slidell). The pair were taken to Boston and imprisoned. Americans cheered and Britons fumed. Whitehall responded with demands so stern that Prince Albert himself intervened to soften the language, though the terms remained intact: release of the two men and a full explanation for such a blatant violation of international law. The deadline for an answer was seven days. While the British government awaited the response, it quickly made plans for strengthening Canada’s defences. Britain’s minister in Washington, Lord Lyons, privately informed the hawkish William Seward of the reply’s contents but waited until December 23 to deliver it officially. That gave him just enough time to lower the diplomatic temperature. At a cabinet meeting on Boxing Day, the Americans sent a sheepish note deploring Captain Wilkes’ actions and promising release of the two prisoners in January.

The United States and Britain came closest to declaring war on each other in the first year of the conflict. In November 1861, an American warship, the San Jacinto, commanded by Charles Wilkes, stopped a British mail packet, the Trent, in international waters off the Bahamas and abducted the Confederate commissioners to London (James M. Mason) and Paris (John Slidell). The pair were taken to Boston and imprisoned. Americans cheered and Britons fumed. Whitehall responded with demands so stern that Prince Albert himself intervened to soften the language, though the terms remained intact: release of the two men and a full explanation for such a blatant violation of international law. The deadline for an answer was seven days. While the British government awaited the response, it quickly made plans for strengthening Canada’s defences. Britain’s minister in Washington, Lord Lyons, privately informed the hawkish William Seward of the reply’s contents but waited until December 23 to deliver it officially. That gave him just enough time to lower the diplomatic temperature. At a cabinet meeting on Boxing Day, the Americans sent a sheepish note deploring Captain Wilkes’ actions and promising release of the two prisoners in January.

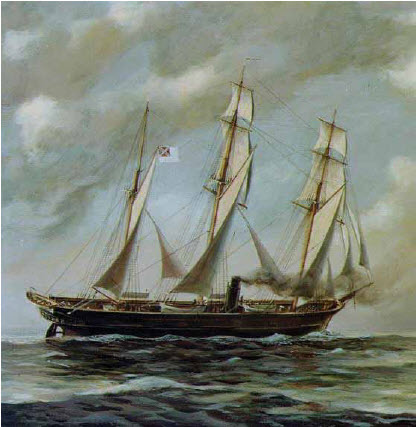

In only two years at sea, the Confederate raider Alabama, powered by both canvas and steam, sailed the Atlantic and Pacific top to bottom, while also going as far afield as South Africa and the Indian Ocean. Its ship’s motto was Aide-toi, et Dieu t’aidera — “Help yourself and God will help you.” Of the total of 158 U.S. ships destroyed by the impoverished Confederate Navy, the Alabama sank 65 of them. Its exploits made it, in Dr. Foreman’s words, “the most famous ship afloat [as the] entire English-speaking world knew her history.” But it would not be afloat much longer. It lost a duel with the USS Kearsarge off France in mid-1864.

In some ways, however, the Alabama was only representative of a much broader effort.

As soon as the war got underway, the United States began blocking Southern ports on the Atlantic (and later New Orleans as well), launching its strategy of trying to starve the Southerners to death. All the South could do was to build ships overseas both to harass U.S. commerce and run the blockade where possible. Remember that Rhett Butler of Gone with the Wind was a blockade-runner by profession. What you won’t learn from the film is that he was probably using a ship built in England or France with financial help from the members of the Royal Exchange in London or cotton brokers in Liverpool. Having no access to Southern ports, Confederate warships like the Alabama, and so many others, were born in Britain or Europe and never saw their home country, for they stalked the world’s shipping lanes, resupplying in whatever neutral ports would have them. Like sharks, they never slept.

So desperate was the Confederate government for ships that it tried to buy some from China. In his new, but posthumously published, book The Alabama, British Neutrality, and the American Civil War (Indiana University Press, US$22.95), the American historian Frank J. Merli calls the coveted Chinese flotilla a “paranaval force, a squadron of some six or eight ships of a class that contemporary terminology might designate coastguard cutters.” Another historian has called it a “mosquito fleet.” In the end, the deal fell through owing to a failure of diplomacy by the various parties.

Canada is where the Anglo-American war, if there were to be one, would have broken out.

Canadians were overwhelmingly against slavery (which John Graves Simcoe had outlawed in Upper Canada in the 1790s). So, too, were Britons not connected to one of the manufacturing cities in the Midlands or to big capital generally. But the English intelligentsia and others, indeed much of the Empire, endorsed the Confederacy, or at least the idea of it. Caught between the lines, so to speak, diplomats had to tread carefully, at least in public. Lord Lyons confided in a letter to Lord Russell, the foreign secretary, that Seward had some plan to tour England on a good-will mission. The British knew it would turn into an ill-will mission instead. Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, joined in, telling Lord Russell that Secretary Seward was “vulgar and ungentlemanlike and the more he is seen here the less he will be liked.” Seward was furious about all the Confederate activity underway in plain sight on Canadian soil, while the governor general of Canada, Lord Monck, struggled to preserve the letter of Britain’s neutrality laws.

For his part, British Prime Minister Palmerston “was not in the least interested in petty recruiting scandals, except as a counterargument to Northern complaints about the Alabama.” His worry, rather, was that the U.S. would take over complete control of the St. Lawrence River and thus keep British vessels from using it. Connected to this in several important ways was the possibility that naval warfare on the Great Lakes, the site of one of most important American victories in the War of 1812, would resume. This, despite the fact that the Rush-Bagot treaty had demilitarized these waters in 1817. For most of the Civil War, the only naval vessel on the Lakes was an American gunboat guarding Confederate prisoners on the southern shore of Lake Erie. But this could change quickly, given the British obligation to defend the Canadas and the South’s extensive (if not always smoothly run) infrastructure at important points along the border. This subject is a highly complex one that a Canadian historian, John Bell, surveys in his new book Rebels on the Great Lakes: Confederate Naval Commando Operations Launched from Canada, 1863—1864 (Dundurn, $27.99 paper). Mr. Bell clearly has infinite patience, an excellent nose for tracking, and a serious but likeable prose style: a combination all too rare.

Once the Civil War sputtered to its end, the U.S. sought recompense from England for allowing construction of the Alabama at an English shipyard (at Birkenhead in Cheshire). It also demanded reparations for all the U.S. merchant shipping lost in attacks by the Alabama and other Confederate raiders, putting the figure at two billion dollars (or, as one especially powerful senator suggested, all of Canada, in lieu of cash). Palmerston reacted angrily but died before the end of 1865. The liberal Gladstone, who became prime minister in 1868, acknowledged the principle involved but thought the dollar amount ridiculous. An international commission was established to consider the matter. The affair dragged on for the remainder of the decade, and beyond.

William Seward, who once proposed to President Lincoln that the U.S. declare war on the whole of Europe as a way of distracting the nation’s mind from the slavery problem, was in an expansionist mood, as usual. Having engineered the American purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867, he now suggested that the British payment take the form of Nova Scotia, the Red River Colony (in what’s now Manitoba) and the land that would come to be British Columbia. To Seward, the last of these was the most important, as it could be merged with Alaska. He died, out of office, in 1872, by which time Hamilton Fish, a new and less combative secretary of state, was in place. The figures appointed to resolve the matter (Sir John A. Macdonald among them) found in the Americans’ favour. In the end, Britain paid $15.5 million, offering an apology but admitting no guilt. The relevant document, the Treaty of Washington, deserves to be better known. Many cite it as one of the first milestones on the road to multilateral and multinational arbitration, the codification of international law, and so on.

Dr. Foreman’s book is full of compelling individuals as well as politics and ideas. For example, some exceptional journalists strut across her pages, most particularly the near-legendary W.H. Russell—“Russell of the Crimea.” It was he who coined the phrase “the thin red line.” He is often said to have invented the profession of war correspondent as well (eroding the tradition by which commissioned officers dashed off occasional despatches even while in the saddle). The Crimean War of 1853-56, in which Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire fought the Russians to settle a bar bet about the Holy Land, was the single greatest influence on the American Civil War — strategically, tactically, even sartorially — but most importantly in the terrible level of carnage that resulted. There is a useful comparison to be made between Dr. Foreman’s work and another new book, The Crimean War in the British Imagination by Stefanie Markovits (Cambridge University Press, US$99).

In the Crimea (where his first-hand reportage caused an unknown Florence Nightingale to take up battlefield nursing), Russell didn’t shy from reporting the true horrors that he saw. He assumed the same tone in America. He preferred a tent full of common soldiers to a seconded front parlour full of generals. As one colleague commented, “He is a good chap to get information, particularly from the youngsters.” So naturally his employer, The Times of London, sent him to America when war broke out there. The newspaper later recalled him, however, on the grounds that he was too sympathetic to the South, or at least not sympathetic enough to the North. Curiously, the same paper had no qualms about Francis Lawley, its reporter who followed the Southern armies and was outrageously blind to their every flaw and misstep. As a reader, I’m delighted to find that Dr. Foreman discusses Edward Dicey, who promoted the Northern armies for the Spectator and wrote what is still an endearing pro-Union memoir, Six Months in the Federal States. It is not to be confused with, but simply contrasted to, Three Months in the Southern States (April, May and June 1863) by Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J.F. Fremantle of the Coldstream Guards. He took leave from the service to travel in all 11 Confederate states, using letters of introduction from one official or another (even Jefferson Davis) to gain an audience with the next general on his list. Studying the Confederate army through the eyes of a professional soldier left him with solid collegial respect for his hosts. His handsomely written book is still in print as a 1991 paperback edition (University of Nebraska Press, US$18.95). Dr. Foreman uses this one, too, to good effect.

To state the matter as simply as possible, then, the most important diplomatic question of the American Civil War was whether to take sides in a divorce (in war as in real life, always a risky proposition). A similar situation, one involving Canada and its numerous allies arose near the end of the First World War and continued on for a time afterwards. In 1917, the year of both the February and October revolutions, Russia deposed the czar (who was executed the following year) and ran through two prime ministers. The country was a shambles of starvation and unrest. When V.I. Lenin came to power, he made good on his promise to withdraw Russia from the alliance of Western powers fighting the Germans and others. Whereupon a civil war erupted between the Bolshevik Red Army and the conservative White Army. Eager for a less unfriendly Russian regime as well as for Russia’s oil (that old story), Canada, Britain and others decided it was a splendid moment to invade Russia from Vladivostok and other points in the Russian Far East where the Whites were strongest. This episode, commonly called the Intervention, is not widely spoken of or taught in today’s Canada, for it proved a singular failure.

Benjamin Isitt examines the mess in close detail in From Victoria to Vladivostok: Canada’s Siberian Expedition, 1917−19 (UBC Press, $29.95 paper). As his title suggests, he pays special attention to one unit that departed from Victoria — but not before staging a small mutiny. Many or most of the men were conscripts. To get some of them onto the transport vessel, officers had to resort to their service revolvers and use their heavy canvas belts as whips. Few of these soldiers who entered through Vladivostok ever proceeded far enough inland to actually reach Siberia, where all the others, coming overland from the north and east, were to join up. Some Canadians, however, did reach Omsk, in the centre of the country. There, in partnership with the British, they were able, for a time, to hold together the White government. It needed propping as it was as wobbly as three-legged table. Its leader, somewhat oddly, was a Czech admiral. Like the Reds, the Whites and their foreign friends were continually battling for control of the Trans-Siberian Railway (ironically, the most significant engineering megaproject of the last few czarist regimes).

Mr. Isitt makes the point that our participation was one more step towards an independent Canadian foreign policy, a matter of great concern and pride, especially given Canada’s role in the late unpleasantness in Europe. The world war had finally come to an end only a few months before the launch of the Intervention, which sputtered on for at least another year. But that’s about the best that can be said of the expeditionary force. Like those of other nationalities, Canadian troops had become entangled in this hopeless effort when they were already sick of war. For many people, the Intervention became a mirrored symbol of the class warfare breaking out at home. Labour unions were major players in fomenting dissent, though radical farm movements and some of the intelligentsia were important as well. The language was often extremist. In their book When the State Trembles: How A.J. Andrews and the Citizens’ Committee Broke the Winnipeg General Strike (University of Toronto Press, $35 paper) Reinhold Kramer and Tom Mitchell quote one union organizer telling a crowd in 1919: “Drafts [that is, conscripts] are being shipped to Vancouver so that they can go across to Russia to massacre the proletariat there. Let us have justice and if not, then blood will be spilled in this country.”

The literature of the Winnipeg General Strike and related events is quite extensive of course, but now, in these times of protests, the subject of labour v. capital in the broader sense is being taken up afresh. Of new books in the field, perhaps the most important (and certainly the best written) is Seeing Reds: The Red Scare of 1918−1920, Canada’s First War on Terror by the Vancouver historian Daniel Francis (Arsenal, $27.95). The last part of the subtitle may sound over the top, but the book isn’t about ideology. Rather, it’s a study of how both sides in a major conflict create propaganda in order to promote paranoia. Were this text in digital form, a reader could indeed do a search-and-replace, substituting the word terrorist for each use of reds, and end up understanding how the strife of one era is so often revisited upon another. Another example, a quite accidental discovery, hit me in 2010 when the University of Toronto Press celebrated the centenary of Canadian Who’s Who by producing a facsimile of the first edition. The personages listed in the 1910 version ($19.95 paper) are exactly those you would expect to find: Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Nellie McClung, and a great many figures in finance and railways. The reprint also includes all the advertisements from the 1910 original. Law firms and insurance companies dominate. But there is also a brazen full-page ad for the Thiel Detective Service, an American-based firm of strike-breakers with offices in Canada’s four largest cities, not to mention the latest trouble spots in Mexico.

George Fetherling’s most recent book is Indochina Now and Then (Dundurn Press).