Argentina is the second largest country in South America and one of the greatest food- and wine-producing nations in the world.

Long before European explorers began to arrive, native Indians lived in Argentina. By 1530, Argentina saw its first Spanish settlers. With a strong immigration policy aimed at incorporating Europeans into the fabric of Argentina, the decade between 1880 and 1890 was most significant, bringing in a wave of almost one

million European immigrants, mainly from Italy and Spain. José Ureta, the embassy of Argentina’s chargé d’affaires in Ottawa, notes that “95 percent of Argentines are of European origin, 50 percent claim to have some Italian blood.” With an influx of Italians came the introduction to Argentine cuisine of pizza, a myriad of pasta dishes, coffee, ice cream, lemoncello (a lemon liqueur) and so much more. Immigrants from other European countries (Britain, France, Poland, Switzerland, etc.) as well as Arabs and Jews also settled in Argentina, each bringing a style of cooking and national recipes that have had a marked influence on today’s food culture. One noticeable example is the country’s tradition of tea time, attributed to the British.

From a gastronomic perspective, Argentina could geographically be divided into four main food regions. The Pampas occupies much of the mid-Eastern portion of the country, then there’s the northeast, northwest and Patagonia, which represents the southern half of the country.

In Pampas, although the original diet of nomadic Indian tribes tended to be very basic — roasted meat and not much else — as cities and settled areas were established, a more balanced food culture evolved in terms of styles of cooking (boiled beef and vegetables, stews, sausages, cold cuts) and the use of derivative products (cheese, milk, milk puddings). With the country’s principal seaport and port of entry for immigrants, the greater Buenos Aires area has always been exposed to an ever-expanding wealth of food cultures from other countries, says Mr. Ureta, “all of which have worked their way across our vast country.”

The northwest, which borders on Bolivia, produces cheese, lemons, sugarcane and Argentine marzipan (using wheat flour, not ground almonds), wine and aguardiente (a clear brandy prepared with distilled fruit juices or wine). But this region is best known as the “kingdom of maize” and is regarded as the centre of any Inca influence remaining in Argentine cuisine. In contrast, the Northeast region (specifically the areas of Formosa, Chaco, Corrientes and Misiones, which border on Paraguay) boasts a unique Guarani cuisine (native to Paraguay), based on Farina (a flour or meal made from cereal grains), manioc (also called cassava or yuca), flour and iname (i.e., yam) root. Mr. Ureta enthusiastically notes: “Dishes are entirely local and can only be experienced when in the area.” In the south of this region, yerba mate is not only part of the culture, but vital to the economy, as Argentina is its greatest export in the world. Regarded as the “green tea” of South America, it is refreshing, stimulating and undisputedly the most traditional of Argentina’s drinks.

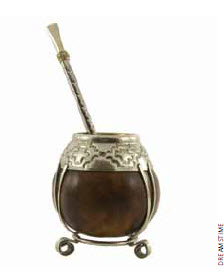

Yerba mate derives its name from a translation of the words “herbs” and “gourd.” Originally, aboriginals chewed the raw leaves of the yerba plant, but in the 17th Century, the Jesuits began to cultivate it for mass consumption and insisted on its use as an infusion, which could be done in various ways. Today, it’s even done by using sachets. However, the traditional preparation is more ceremonial. Argentines place crushed dried yerba leaves and stalks in a dried gourd. They then moisten the leaves with cold water before adding hot (not boiling) water to fill the gourd. A bombilla, a metal straw with a perforated bulb at the end, then filters out the solid particles. Designed for sharing, the gourd is passed from person to person with everyone drinking from the same bombilla, with the hot water replenished as required. A similar tradition takes place in Paraguay but there, it’s called tereke, and is made with cold water, ice, and, at times, a bit of orange zest.

From the fourth region, the vast semi-arid Patagonia, comes some of the world’s finest lamb. Oysters, mussels and the celebrated king crab are harvested from its coastline. In the Andean valleys and foothills, local economies thrive on fruits, mushrooms, trout, game and fine wines.

Today, Argentines enjoy a diet high in protein. Although the consumption of chicken, pork and fish has increased dramatically in recent years, Argentines remain the highest consumers (per capita) of red meat in the world. The grass-fed, free-range beef of Pampas and Patagonia is world famous for its tenderness, flavour, reduced saturated fats, higher healthy omega-3 fatty acids and minimal injections of hormones. Argentina’s internationally renowned barbecue (asados) features prominently in Argentina’s food culture, with strong emphasis on ceremony, long happy hours of socializing, cooking, dining and drinking. Slow grilling over charcoal (never gas) produces tender, juicy results. Barbecued roasts, beef steaks and ribs are particularly popular. Other favourites include grilled chorizo (pork sausages), blood sausages, crisp milanesas (sweetbreads), chitterlings (animal intestines), chicken, lamb and goat. But no Argentine asados would be complete without the indispensable chimichurri, a vinegar-based, peppery sauce made with parsley and other herbs, garlic, oil and vinegar. Salads, potatoes and other vegetables are also on the menu.

One might suggest that much of Argentine cuisine tends to preserve the basic flavour of the original product. Meat is generally grilled or roasted with only salt and pepper. Marinades are simple and light; sautéeing is preferred to deep-frying; with the exception of cumin, herbs (not spices) are used and even those are limited; few dishes are “spicy” hot.

In general, and excluding the foods of ethnic groups, Argentine cuisine is based on a small number of standard dishes — grilled or roasted meats, cold cuts, sausages, empanadas (stuffed bread or pastry), potatoes, corn, flans and dulce de lèche (sugar-thickened and carmelized milk) flavoured desserts.

Argentines typically enjoy a light breakfast of bread or rolls with jam and coffee. Lunch choices vary from something light to a large hot meal (particularly for the more affluent and the farmers), to empanadas for school children. In late afternoon, teatime with sandwiches and cake appeases appetites until dinner, which begins sometime between 9 and 11 p.m.

Enjoy my asados version of grilled beef steak with chimichurri. Buen provecho!

Grilled Steak with Chimichurri

Makes 4 servings

1 1/4 lb (575 g) boneless beef grilling steak (strip loin), 1 1/2 inch (4 cm) thick

2 tbsp (30 mL) olive oil, preferably garlic-infused

To taste, salt and crushed black peppercorns

Chimichurri:

3/4 cup (180 mL) fresh parsley leaves (packed)

1/2 cup (125 mL) fresh cilantro leaves (packed)

1/4 cup (60 mL) chopped fresh chives

1 1/2 tbsp (23 mL) fresh thyme leaves

1 tsp (5 mL) minced fresh garlic

1 tsp (5 mL) red pepper flakes

1 tsp (5 mL) sugar

3/4 tsp (4 mL) ground cumin

1/2 tsp (3 mL) salt

2/3 cup (170 mL) olive oil

2 tbsp (30 mL) red wine vinegar

2 tbsp (30 mL) fresh lemon juice

1. To make the chimichurri, place all chimichurri ingredients in a blender and process until well blended. (Makes 1 cup or 250 mL.)

2. Shortly before grilling, rub steak with olive oil and sprinkle with salt and crushed black peppercorns.

3. Place steak on a preheated barbecue grill over medium to medium-high direct heat. Keeping the hood down as much as possible, grill steak to desired degree of doneness. (Note: For rare, grill steak about 3 minutes per side and if desired, sear edges briefly — just a matter of seconds.)

4. Transfer steak to a cutting board, cover loosely with aluminum foil (shiny side down) and allow meat to rest for 10 minutes.

5. Slice into 1/3 inch (0.8 cm) slices and serve with chimichurri sauce on the side.

Make ahead tip: Chimichurri may be prepared in advance, placed in a well-sealed jar or airtight plastic container and refrigerated for up to 5 days.

Margaret Dickenson wrote the award-winning cookbook, Margaret’s Table — Easy Cooking & Inspiring Entertaining, and she hosts the Rogers TV series, Margaret’s Table (www.margaretstable.ca).