In Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey, the ethnic origin most often selected by respondents was Canadian, reported by more than 10.5 million people. It was followed by English, French, Scottish, Irish and German.

Canada is often called a land of immigrants. And it is true that all Canadians are either from somewhere else, or the descendants of people from somewhere else. Through 18th-Century British exploration, 19th-Century gold rushes and settlement of the West in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, Canada became a significant immigrant-receiving nation.

Migration of people from one country to settle in another has been central to Canadian history. Canada has, of late, been chastised for the racial and ethnic biases of its immigration history. However, the very idea of nationhood — the concept of an “us” and a “them” — signifies exclusion, so it stands to reason that populating the country would involve including some and excluding others. That exclusions were made on the basis of race and ethnicity is part of the dark side of Canada’s history. As distasteful as the model of exclusion is, the path to inclusion has contributed to Canada’s reputation for multiculturalism.

Economic development has always been tied to Canadian immigration. The fur trade opened the continent to exploration and ultimately impelled immigration to the New World. Although the first migration of people to North America came from Asia 20,000-40,000 years ago, we tend to begin the history of Canadian immigration when Pierre de Monts and Samuel de Champlain established a settlement at Île St.Croix in 1604, and at Port-Royal, Acadia, in 1605.

The first settlers — or immigrants — to Canada were the Acadians. These French settlers established a vibrant colony at Port-Royal, taming the high tides of the Bay of Fundy with dikes to create rich fields of hay to feed their livestock, irrigating crops, establishing alliances with the Mi’kmaq and the Maliseet and trading with English colonists in America. The colony’s administration changed hands several times, but became English after the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-13), when the Treaty of Utrecht ceded Acadia to Britain. The treaty included the forced departure of the Acadians, who showed little inclination to move to the new French colonies, which were less suited to their agricultural system.

British authorities at Port-Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal) interfered with their government’s transfer decree, concerned about upsetting the balance of the area’s population and removing the farmers needed to support the garrison. The English made little attempt to colonize the area, renamed Nova Scotia, until 1749. They required the Acadians to swear an oath of unconditional loyalty; the Acadians would agree only to an oath of neutrality. Britain, determined to make Nova Scotia “truly” British, brought in its own settlers and deported the Acadians. The deportation (1755-62) shipped the population to English colonies along the east coast as far south as Georgia. Many perished from hunger or disease or were lost at sea.

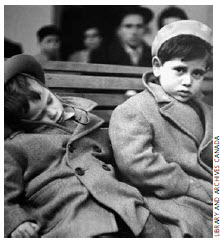

The British Conquest (1759-60) gave Canada to Great Britain and suspended migration from France, but did not impel English immigration. The Empire paid little attention to the Quebec colony but soon had to accept thousands of United Empire Loyalists, British subjects who had settled in the original Thirteen Colonies in the U.S. and were displaced by the American Revolution because of their support for Great Britain. The early Loyalists were Canada’s first political refugees, many of whom migrated to Canada because they feared retribution or did not wish to become American citizens.

The main waves of Loyalist migration came in 1783 and 1784, assisted by imperial authority in the form of Sir Guy Carleton, governor of the Province of Quebec. The military gave the settlers supplies and organized the distribution of land. Most were farmers, not wealthy nor of high social rank, and ethnically mixed. They included White Loyalists with slaves, free Blacks and escaped slaves, and Six Nations Iroquois. The Black Loyalists were 3,000 African-Americans drawn north by the British promise of “freedom and a farm.” It was a promise unfulfilled; the land grant system became corrupt and many received a mere quarter-acre rather than the promised 100 acres for the head of household and an additional 50 for each family member.

Into the mid-19th Century, immigration from England, Scotland and the U.S. slowly began to fill the best arable land. These immigrants generally reflected the heritage and values of the established community. The arrival of Irish settlers, driven from their homeland by the great Irish potato famine, represented Canada’s first significant influx of foreign immigrants (there were already Irish immigrants in Canada). They generally spoke English, but they differed from the majority socially, culturally and religiously.

The “Famine Irish” had been tenant farmers living in poverty and dependence. In Canada, they were not enthusiastic about farming. They provided a mass of cheap labour that helped fuel the economic expansion of the 1850s and 60s, but were viewed as Roman Catholic intruders suspiciously loyal to the Crown. They also tended to migrate to the U.S., a practice that continued into the 20th Century, meaning their impact on Eastern Canada was more significant than in the West.

In the late 19th Century, the Canadian Prairies were opened to settlement, though that settlement first required establishing a market for prairie agricultural products. Wilfrid Laurier’s government implemented large-scale immigration with an aggressive program delivered by Clifford Sifton, minister of the interior. For the first time, Canada sought agricultural settlers from places other than the British Empire, Europe and the U.S. As Sifton declared, “I think that a stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for 10 generations, and a stout wife and a half-dozen children is good quality.”

Sifton’s statement reflected neither government policy nor public sentiment; both were unreceptive to “stalwart peasants in sheepskin coats,” a reference to Ukrainian farmers. The popular idea of “good quality” agricultural immigrants was, in order of preference, British and American, French, Belgian, Dutch, Scandinavian, Swiss, Finnish, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, German, Ukrainian and Polish. The majority of English-speaking Canadians feared that hordes of “strange” peoples would threaten Protestant Canadian society. Others held more tolerant opinions, understanding that immigrants were necessary for building the country, that their children would become integrated into the mainstream of society and that they were here to stay. Nevertheless, welcoming “them” to join “us” created a demand for immigration policies that restricted admission by ethnicity or race.

Populating the “last best West,” the promotional term for the Canadian Prairies, brought Ukrainian immigrants, farmers and labourers from Galicia and Bukovina, fleeing oppressive economic and social conditions in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Seeking meadowland, water, wood and neighbours who spoke their language, they settled in the aspen parkland of the Prairies, from southeastern Manitoba through central Saskatchewan to the Rocky Mountain foothills west of Edmonton, with several Ukrainian block settlements established by 1914.

Among the homesteaders were settlers of German origin, though most came from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires and the Balkan countries, not the German Empire, which had colonized those areas in the 18th Century. German migration to Canada began long before the great western migration; the oldest cohesive German settlement in Canada developed in Nova Scotia between 1750 and 1753 and Germans were among the Loyalist migration. Despite anti-German sentiment during the First World War, in 1918 Canada admitted 1,000 Hutterites and 500-600 Mennonites fleeing American intolerance. All but one of the U.S.’s 18 Hutterite colonies entered Canada on the basis of an 1899 order-in-council that granted them immunity from military service. Following the Second World War, Canada admitted 15,000 Germans as part of its postwar policy of resettling displaced persons from Europe.

Opening the West relied on the development of a transnational railway. Much of the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the West was done by immigrants from South China. Chinese immigrants had begun arriving in Canada in 1858 from San Francisco to prospect for gold in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley. Canada’s first Chinese community was Barkerville, B.C., with others established as the railway extended eastward. Between 1880 and 1885, 15,000 Chinese workers completed the B.C. section of the CPR.

The first Opium War (1839-42) and the T’ai P’ing Rebellion (1850-64) created poverty and political upheaval in China that forced many peasants and workers to seek opportunities elsewhere. From 1885, Chinese migrants had to pay a $50 “head” tax to enter Canada, the only ethnic group taxed for admission. By 1900, responding to public protest, the Liberal government restricted Chinese immigration further by raising the head tax to $100. B.C. politicians demanded it be increased to $500. The federal government appointed a Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration, which concluded that Asians were “unfit for full citizenship … obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state.” In 1903, Parliament raised the head tax to $500. On July 1, 1923 (“Humiliation Day”), the Chinese Immigration Act was replaced by legislation that virtually suspended Chinese immigration. The legislation was repealed in 1947.

Japanese immigrants were treated as poorly as the Chinese. The first known Japanese immigrant was Manzo Nagano, who arrived in B.C. in 1877. In 1907, at Canada’s insistence, Japan limited migration of men to Canada to 400 annually. In 1928, Canada placed further restrictions on the Japanese, limiting immigration to 150 annually. During the Second World War, fears were rampant that the Japanese represented a national threat, particularly after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and forced the surrender of the British garrison at Hong Kong. That imagined fear initiated policies of detention and dispossession and the removal of nearly 21,000 Japanese from their homes; 75 percent were Canadian citizens. They were placed in detention camps across the country and their property sold by the government. In 1945, Japanese Canadians had to choose between deportation to war-torn Japan or dispersal east of the Rockies. Most chose the latter.

Perhaps the most diverse immigrant population in Canada are South Asians, people from, or descended from, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, representing several major languages, multiple religions and hundreds of discrete ethnic groups. The first to reach Canada came to Vancouver in 1903, mainly Sikhs who had heard of Canada from British Indian troops who had traversed Canada in 1902 en route to Edward VII’s coronation. Attracted by high wages, South Asians began immigrating in large numbers. By 1908, they numbered 5,209 men, primarily Sikhs from Punjab, who had left their families to find work in Canada. The B.C. government, seeing a racial threat, imposed restrictions.

In 1908, the Canadian government, yielding to public pressure to stop immigration from India, established an order-in-council that required individuals to reach Canada from India by continuous passage, at a time when no steamship line provided such service, and to be in possession of $200. The conditions were challenged by a group of prospective South Asian immigrants who chartered the freighter Komagata Maru, but were forced back to India by immigration officials. The continuous-journey provision remained law until 1947. Community pressure and Indian government action forced Canada to allow the wives and dependent children of South Asian Canadians to immigrate and by the mid-1920s, the families of the immigrant South Asian men began to arrive.

In 1951, Canada replaced the continuous-passage regulation with an annual immigration quota. As racial and national restrictions were lifted in the 1960s, South Asian migration grew significantly. Canada also began to receive immigrants from Southeast Asia, which includes 11 countries, 10 of which are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN, whose members include Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.) Although groups of Southeast Asians have arrived in Canada for this country’s opportunities and advantages, many have come as refugees, most famously the Boat People of the late 1970s.

By the late 1960s, racial discrimination had been removed from immigration legislation and regulations. Canada proclaimed its Multiculturalism Policy in 1971, the first country to execute such legislative framework. In 1996, “Canadian” was included as an ethnic heritage on the national census. By 2001, the census recorded more than 200 ethnic origins and the population of those of British, French or Canadian ethnic origins had decreased to less than half the population. Migration has increasingly shifted from Europeans to Asians, and Canada has become home to an increasing number of races, religions, languages and cultural traditions.

Much thought has been devoted to Canada’s national identity, and whether or not it has one, in this mélange of immigrant ethnicities. However, the ethnicity of the individual does not replace one’s identity as a Canadian. Rather, the country’s multiple ethnicities define its people.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky is an Alberta writer.