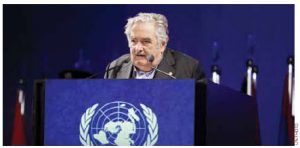

Last month, the lower house of Uruguay’s bicameral parliament voted to legalize the cultivation, distribution and sale of marijuana by adults in the country. The bill is almost certain to pass through the Senate and be signed into law by President Jose Mujica in coming weeks.

If the bill passes, Uruguay will have the most progressive marijuana legislation of any country in the world. Even in Amsterdam, where small quantities of the drug are openly sold and consumed in the city’s famous coffeehouses, marijuana remains technically illegal. In fact, an array of countries around the globe, from Portugal to Mexico to Colombia, have decriminalized possession of small quantities of marijuana, but in all of these cases, commercial cultivation and sale of the drug remain felony offences. This means that all of the profits from one of the biggest cash crops in the world go straight to organized crime.

Uruguay’s plan addresses this issue by putting cultivation and distribution under government control. The set price will be slightly lower than the current illicit street price, which will certainly lure most of the country’s 120,000 marijuana users away from the violent illegal market.

Uruguay’s plan, while unique in its ambition, reflects the rapidly evolving views of drug policy throughout Latin America. Shortly after his November 2011 election, Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina called for an open dialogue about the “decriminalization of the production, the transit and, of course, the consumption” of all drugs. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has said he would welcome legalization, and former Mexican president Felipe Calderón has called for “market alternatives” to prohibition.

In Canada, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau has sparked a debate about the legalization of marijuana, after which Prime Minister Stephen Harper left the door open to exploring new enforcement options for possession, such as fines.

These leaders, like an increasing percentage of Canadians and Americans, have come to the realization that drug prohibition has failed and society must devise a smarter, more effective and less destructive approach to the issue of drug abuse.

I came to that conclusion following a 13-year career with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, which included five years working in embassies and consulates in Latin America. Every year, the U.S. government spends more than $26 billion waging the drug war and arrests nearly one million people for drug-related crimes, yet drugs remain available in every community in the country and addiction rates are unchanged. Meanwhile, more than 60,000 Mexicans have been murdered in drug trade-related violence since 2006.

The United States holds a unique and destructive role in the global drug trade. It is the world’s largest consumer country, the largest importer of illegal drugs, the industry’s financier and a leading arms supplier to Mexican cartels. In short, it imports drugs and exports violence. It also exports bad policy. Despite growing calls for reform throughout Latin America and shifting public opinion at home, the U.S. government remains steadfast in its demonstrably unsuccessful prohibitionist strategy.

Worse, it refuses to join the growing hemispheric debate about drug war alternatives. This “big stick” approach is an affront to its southern neighbours and reflects a shocking callousness to the drug war’s ravages in their countries.

The greatest diplomatic challenge facing the United States in the coming century will be how to advance national interests in an increasingly multi-polar world. The country’s ability to compel other nations’ compliance with U.S. wishes, simply because it’s stronger and richer, will diminish as the influence of Brazil, China and other powers grows. This is not only a challenge, but an opportunity. The U.S. may well find that a more diverse marketplace of ideas will engender bold new solutions to shared problems.

Uruguay’s pending legalization of marijuana is one such solution. While not a panacea, the regulated legalization of marijuana will necessarily take money out of the hands of violent criminal gangs and focus law enforcement resources on violent crimes. If the U.S. is serious about reducing the violence, death and destruction the drug war creates, it would do well to follow Uruguay’s lead.

Former DEA senior intelligence research specialist Sean Dunagan is a speaker for Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a group of police officers, judges, prosecutors, federal officials and other law enforcement officials who oppose the war on drugs.