Canada’s immigration policy has often been praised as a model of how immigration programs should be managed. For many years, there was reason for this praise, but in the early part of the current decade, changes in the policy have led the federal government to lose control over the program. A brief history of how the policy has evolved since the end of the Second World War will illustrate where the policy went wrong.

From the end of the Second World War until 1962, Canada’s immigration policy was based on the practice of selecting immigrants, with few exceptions, from Britain, Europe or the United States. It was, in effect, a “white-only” policy. The policy was formulated following a speech in Canada’s House of Commons in May 1947, by prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. The prime minister declared categorically that Canada was “perfectly within her rights in selecting the persons whom we regard as desirable future citizens.”

He went on to say: “There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that the people of Canada do not wish as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population … The government, therefore, has no thought of making any change in immigration regulations which would have consequences of the kind … The essential thing is that immigrants be selected with care and their numbers be adjusted to the absorptive capacity of the country. This will clearly vary from year to year in response to economic conditions.”

The prime minister’s statement formed the basis of the Immigration Act of 1952, which provided legislative authority to operate an openly discriminatory policy of selecting immigrants from traditional source countries. The policy lasted for the following 10 years and, during this period it was extremely difficult for non-white immigrants to enter Canada.

Increasing criticism of the policy, and the August 1960 passage of prime minister John Diefenbaker’s Bill of Rights led to a change in immigration regulations, permitting individuals from any country to apply to immigrate to Canada if they met the applicable selection criteria (meaning they possessed the education, skills and training considered adequate to become established in the Canadian labour force.) However, the regulations permitting a wider degree of relatives to be sponsored from Britain, Europe or the United States than from other countries remained unchanged and the locations of Canadian visa offices were almost exclusively in those three areas. In reality, therefore, discrimination was still evident in Canada’s immigration program.

In 1966, the government introduced major changes in immigration by creating the Department of Manpower and Immigration, which joined the National Employment Service and the Immigration Service. This structural change followed a government White Paper recommending that immigration focus on the objective of enhancing the Canadian labour force by selecting skilled and professional migrants with occupations needed in Canada. The family-class category should be restricted to a narrow range of dependent relatives: spouses, minor children and aged parents and grandparents.

In 1967, the government passed new regulations incorporating the recommendations of the White Paper and eliminating the final vestiges of racial discrimination in its immigration policy by allowing family-class immigrants to be sponsored regardless of their country of origin. The regulations also introduced the “point system” for selecting immigrants destined to the labour force.

The selection system consisted of nine factors of assessment considered to be useful in helping the interviewing officer decide if the applicant could become satisfactorily established in Canada. Financial help would only be available in emergency situations.

The nine factors were each allocated a specific number of points: education (20 points); personal qualities (15 points); occupational demand (15 points); occupational skill (10 points); age (10 points); arranged employment (10 points); designated occupations in chronic short supply (10 points); language (10 points); relative in Canada willing to help (5 points); area demand for employment in applicants destination (5 points). The arranged employment and designated occupation factors were worth 10 points, but only one of them could be considered.

An applicant needed to obtain 50 points out of 100 to qualify. However, the new regulations also gave the interviewing officer the discretion to refuse or accept an applicant regardless of the points achieved. This discretionary power to override the points was thought essential because the judgment of experienced visa officers was considered more important than an arithmetic model. Furthermore, discretion added a necessary flexibility to the system. (Over time, statistics showed that positive discretion was used far more often than was negative discretion.)

Canadians had no idea of just how revolutionary the 1967 regulations were. The new policy opened the immigration door to the world and in a short period, as new visa offices were opened in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, the composition of the immigration movement was radically transformed. As economic conditions in postwar Europe improved, fewer people there were interested in migrating and soon Canada became a favourite destination for people from the rest of the world. Between 1971 and 1981, approximately 52 percent of the immigrants admitted were from Asia, Africa, South America or the Caribbean.

The 1967 regulations were not enacted by an act of Parliament. There was no debate by members of the House of Commons; no press releases were issued and the media did not report on this historic development. The regulations were passed by an order-in-council, meaning that the regulatory changes were authorized by the cabinet, and quietly published in the Canada Gazette following a short statement by the minister of Manpower and Immigration in the House. It is difficult not to conclude that the government of the day did not wish to have this major immigration policy change brought to the attention of Canadians, nor did it want to see the subject debated in Parliament.

A further reason the dramatic change in immigration policy did not become an issue of public attention or controversy was because the new global policy was working. The immigrants, from whatever source country, were successful. They were finding jobs, making a contribution and were not a burden on the public purse.

The key to the success of the new global policy rested on two factors. Firstly, shortly after the new regulations were passed, it was discovered that the system lacked a mechanism to manage and control numbers. In the knowledge there would always be many more thousands of applicants who could meet the selection criteria than could be accepted, it was essential the system have the means of regulating and restricting annual numbers. This was done by raising the pass mark or by allotting zero points for the occupational demand factor, which then meant automatic refusal despite the overall marks received. In this way, annual numbers could be adjusted and controlled in accordance with employment conditions.

In fact, the annual immigration flow after 1967 until the 1990s remained relatively low; only exceeding 200,000 once during that period (1974). The second factor of success was that the immigrants were carefully selected and counselled to ensure that those issued visas were able to find employment quickly and become successfully established. The point system of selection of immigrants destined to the labour force, coupled by a restricted family reunion program, was working.

What went wrong?

In 1976, a new immigration act was introduced to finally replace the outdated 1952 legislation that had lasted for almost a quarter of a century. The new act, contrary to what was done in the past, followed extensive public discussion and debate across Canada and in Parliament. The discussion was centred on a government Green Paper that outlined many of the crucial issues related to immigration policy and its impact on the future demographic composition of the country.

For the first time, the Green Paper raised the issue of immigration and the environment by stating: “To many Canadians living in a modern industrialized and increasingly urbanized society, the benefits of high rates of population growth appear dubious on several grounds. Canada, like most advanced nations, counts the costs of more people in terms of congested metropolitan areas, housing shortages, pressure on arable land, damage to the environment — in short, the familiar catalogue of problems with which the most prosperous and sophisticated societies are currently endeavouring to cope.”

Determined that immigration policy must be the subject of concern and debate by all Canadians, the government established a special joint committee of the Senate and House of Commons to provide input to the legislation. The committee travelled across Canada for 35 weeks holding public meetings and recording the opinions of groups and individuals. It concluded its hearings by recommending that Canada should continue to accept immigrants in moderate numbers, and put forward 64 additional recommendations, the majority of which were accepted by the government.

The 1976 Act retained the basic selection system and definition of the family class, but gave a broader role for the provinces in the selection of immigrants and provided for the federal government to enter into formal immigration agreements with the provinces. For the first time, the act also required the government to table in Parliament its proposed level of immigration for the coming year. In many respects, the 1976 Immigration Act could be seen as a model piece of progressive legislation that brought a framework of legislative authority and transparency to what previously had been done quietly behind doors and by regulatory change alone.

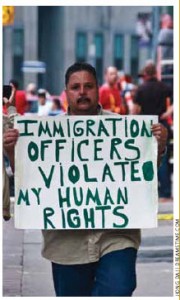

However, over time, the advances made in the 1970s were set back by a series of developments that have gradually replaced an immigration policy that had worked for the benefit of Canada and the newcomers. The primary reason the system has broken down is because all of our political parties have come to regard the importance of immigration in purely political terms. Immigrants are seen as potential voters for the party and each party advocates for increased levels of immigration. They are aided in this by a number of special interest groups and by most of the media. Numbers are seen as the most important factor and the name of the game is to increase the flow, regardless of economic conditions.

This radical shift in policy occurred in 1990 when the Progressive Conservative government decided to raise the annual immigration level to 250,000 despite evidence Canada was heading into an economic downturn. The minister responsible, Barbara McDougall, argued that higher levels would help the party to build stronger ties with ethnic communities. The economic forebodings expressed by finance minister Michael Wilson, were overruled. This decision marked a turning point in how immigration levels were to be managed in the years ahead, not only by the Conservatives, but also by the Liberals. The New Democratic Party promised even higher levels should it form the government.

When the Liberals replaced the Progressive Conservatives in the 1993 election, they continued the policy of mass numbers and in 2001 introduced a new immigration bill which, as the then-minister Elinor Caplan declared, was designed to say “yes” more often to immigrants and refugees. The new legislation came into effect in 2002 and proved to be a disaster.

Almost immediately, a backlog of successful applicants began to build up in embassies abroad. Either by design or accident, the new act stipulated that anyone who met the newly designed selection criteria “shall” be accepted. In addition, the new selection criteria heavily weighted the points allotted for years of education and dropped the “occupational demand” factor, thus removing from the system any mechanism for regulating numbers. The act also broadened the family class to include parents and grandparents of any age and incorporated this definition into the act itself rather than in the regulations. Soon there was a backlog of 600,000 applicants waiting for their visas, later to grow to more than a million.

Included in the backlog were thousands of young Asians who, because of their years of education, were able to meet the criteria for selection. On the other hand, many highly skilled workers needed in Canada were unable to qualify because they did not score high on the formal education factor. More seriously, since employers were not able to get the workers they needed as immigrants — because the workers were waiting for months in the backlog or didn’t qualify — they began to bring them to Canada as temporary foreign workers.

This gave rise to another serious problem. For years, Canada had avoided making the grave mistake made earlier by many European countries in the 1960s and 1970s of bringing in thousands of temporary workers to fill short-term labour needs. Few of those who came had any intention of leaving when their term of employment ended and today have formed a troubling underclass in many of Europe’s major cities.

Temporary workers do not have to meet the federal selection criteria. Many of them are unskilled, have little educational or language qualifications and are willing to work for less pay than Canadians. Their numbers are high — almost one-and-a-half million have entered since 2008. While it can be assumed many may now have left, there is no way of knowing this. Canada does not have any exit control system and there is no procedure for following up or controlling the movements of temporary workers. Although steps are under way to better control this program, it may be too late. Certainly the numbers here now will not easily be removed.

Although immigration has been a shared responsibility between the federal and provincial governments, only recently have the provinces, with the exception of Quebec, signed formal immigration agreements. Quebec’s Quiet Revolution led to the desire of that province to gain control of immigration selection in the realization that demography was critical to the province’s nationalist aspirations. The first two agreements signed in 1971 and 1975 did not give Quebec the power to select its own immigrants, but in 1978, the Cullen-Couture Agreement did.

The financial terms of the agreement were generous to an extreme in Quebec’s favour. To compensate for the costs of reception and settlement services, Quebec was guaranteed a base sum of $90 million annually, but that sum could escalate according to a complicated formula related to an increase in total federal expenditures (excluding debt services) and the proportion of immigrants entering Quebec in relation to its proportion of the total Canadian population and any increase in the number of non-francophone immigrants entering the province.

Furthermore, as icing on the cake, the yearly amount paid to Quebec cannot be less than $90 million even if the numbers of immigrants to that province diminish or overall federal spending decreases. It was such a good deal that Quebec insisted the wording be incorporated into the 1990 Meech Lake Accord. When that accord was rejected, the agreement was quickly reformulated as the Canada-Quebec Accord at Quebec’s insistence and signed in 1991.

As was to be expected, when the other provinces discovered the sweetheart deal given to Quebec, they, too, entered into the game and now all have signed agreements with the federal government (none has won as generous a deal as Quebec). These agreements are extremely costly and they essentially take the selection of many immigrants out of the hands of the federal government.

Quite apart from the immigrants selected by the provinces, it is evident that the federal government has lost control of the immigration program and is, in fact, responsible for a small part of the annual movement of people to Canada. If we look at the 257,515 immigrants who arrived in 2012, we find that only 38,577 of them were in the skilled-worker category — roughly 15 percent of the total. The remainder were largely the 52,700 spouses and children who accompanied the workers; 64,901 family members chosen by their relatives in Canada; 23,652 nominated by the provinces; 23,000 refugees; roughly 9,000 live-in caregivers; and 8,863 humanitarian cases. So we have more than 182,000 immigrants not selected because they are able to help our labour force or develop our economy. Yet the government continues to tell Canadians we need more than 250,000 immigrants a year.

Studies have shown the immigrants arriving since the 1990s are not doing well and many are living below the poverty line. One 2011 study, by economists Herbert Grubel and Patrick Grady, entitled Immigration and the Welfare State, concluded that the value of services and benefits received by the immigrants who arrived between 1987 and 2004 exceeded the taxes paid by them by between $16.3 and $23.6 billion in one fiscal year (2006). This study received very little coverage by the Canadian media.

Sadly, our immigration program has been transformed into a mass visa factory. The pressure of getting numbers has meant that the vast majority of immigrants are not even seen or interviewed by visa officers before arrival. The selection is now being done by reviewing paper qualifications only. The implications of this, from a security point of view alone, are staggering, but it helps explain, as well, why many of our immigrants are not doing well.

To be fair, former immigration minister Jason Kenney deserves high praise for a number of reforms he introduced, including eliminating the backlog, modernizing the dysfunctional asylum system and beginning to exercise better control over the temporary foreign-worker program. However, it is the policy of admitting 250,000 or more immigrants each year, without regard to labour force realities, that needs attention.

In his first press conference after being appointed minister in 2008, Kenney said the immigration system was broken and that it was his job to fix it. Let us hope his successor, Chris Alexander, will carry on the good work and get the federal government back in the immigration business.

After all, immigration is not just about numbers. For the past 25 years, Canada has been accepting newcomers at close to one percent of our population each year. This is a very high number. The U.S., by contrast, accepts about 0.4 percent. Most of our immigrants have been settling in the two urban areas of Toronto and Vancouver. And as Ontario’s environment commissioner warned in his year 2000 report, any prospect of Ontario absorbing an additional 4.4 million to six million immigrants in the next 25 years, as it is planning to do, is, from an environmental perspective, “simply not sustainable.”

One of the most serious problems involving public policy issues in Canada is the seeming inability of our politicians to recognize when policies that served the nation well in the past have, over time, become obsolete. This is clearly the case with immigration. Sadly, the old myths live on and our politicians and most of the media cling to the idea that Canada must rely on mass immigration to progress. This idea is a conviction without evidence and a vote of non-confidence in our ability to educate and train our own young people to meet our labour force needs and the economic challenges of a new century.

James Bissett is a former Canadian ambassador and was executive director of the Canadian Immigration Service from 1985 to 1990. He is on the board of directors of the Centre for Immigration Policy Reform.