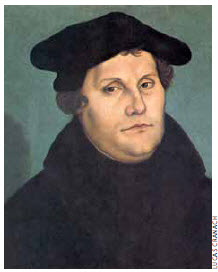

Martin Luther and Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian fruit vendor who set himself ablaze, may not seem to have much in common, but they both dropped a spark into much accumulated dry kindling and timber. That set off blazes that led to sectarian violence, revolution, additional repression and war.

Martin Luther’s nailing of his 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on Oct. 31, 1517, is usually thought to mark the beginning of the Reformation; Bouazizi’s self-immolation on Dec. 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, led to the Arab Spring, which may become the Arab Reformation — and that is not necessarily a good thing.

Following 9/11, it became fashionable, among many westerners and Muslims such as Salman Rushdie, to call for an Islamic Reformation. The idea was that the Reformation gave birth to European tolerance, free thought and religious liberty.

But few of these commentators understood the cost or how the Reformation supposedly led to these outcomes. The Reformation was a bloody, massacre-filled, intolerant affair and now, five centuries later, something similar is being played out in the Arab world. A better understanding of the similarities along with lifting the rose-coloured view of our own past can help provide lessons that may spare the Arab world some of the horrors perpetrated in Europe.

The Reformation: Anything but genteel

Though varying in details and proportions, the tinder and wood for the Reformation and the Arab Spring are largely the same — sectarian and ethnic divisions; holier-than-thou religious conviction that permits, even demands, killing your opponents; a dissatisfaction with the existing power structure; repression and an underlay of political and power conflicts. While there are many differences between the two, the bloodshed flows from the similarities: a more-or-less common culture uncomfortable with its structures, questioning its basis and rife with internal divisions.

In both cases, the proponents of change want(ed) literally to “re-form” their world. Luther provided a religious spark, Bouazizi, an economic, political one. But in both cases, the conflagration quickly spread across the spectrum.

Internal conflict arose with the many different visions of the “re-formed” world: In Europe, Catholic versus Protestant; Calvinistic, Lutheran, Puritan, often against each other, as well against Catholicism; in the modern Arab world, Sunni versus Shia versus secular; in both, a bewildering number of border, political and dynastic disputes; state power versus religious power versus individual rights — to name but a few fault lines.

The “what if?” scenarios

In the present conflagration, many imagine “what ifs” leading to a sunny world: What if the secularists had won in the Egyptian presidential election, as they nearly did; what if Mohammed Morsi had pitched a broad tent; what if the West had intervened early in Syria?

The “what ifs” are fraught with hazard. Had the Egyptian secularists won, they would have inherited a horrid economy. They might have fared better economically than Morsi, but no one would have known of his incompetence, and the secularists would have suffered mightily in public opinion for the lousy situation, powering the Muslim Brotherhood and further divisions. For Morsi to have pitched a broad tent against the obvious inclinations of the Brotherhood, he needed Nelson Mandela status, but Mandelas are rare and Mandela built his inspirational power over decades — no such Mandela existed, or probably could exist, in Egypt. The West did intervene early in Libya, yet Libya is descending into chaos and extremists are gaining strength, intimidating the opposition and beginning to take control of territory.

Such “better worlds” are unknowable and are pure speculation; it might well be that the horrors and dangers would simply have assumed other forms. This is because many countries in the Arab world have yet to experience the deep fatigue that resulted from Reformation-era conflicts.

Thus, we will argue that the key policy lesson from this is that the West can do little to resolve the deep divisions in the Arab world; the flames of conflict will have to burn themselves out. However, taking this lesson, we will argue that focusing on economic issues can mitigate divisions and pave the way for stable democracy.

The Reformation and war

The Reformation period was as bloody as anything yet seen in the Arab world — 25 to 40 percent of the population of northern Germany was killed by war, internal violence or disease, which flourishes in times of violence. The massacre at Mérindol brings to mind the horrors of Syria. Francis I of France ordered the attack to punish the Waldensians, a Protestant sect, in the Northern Italian Alps. Virtually the entire population of Mérindol and the inhabitants of about 25 nearby villages were slaughtered.

So how did the Reformation become known for introducing tolerance? Europeans simply burned themselves out after a century-plus of religious war. Catholic armies marched up and down Europe killing Protestants; Protestant armies marched up and down Europe killing Catholics and, for that matter, other Protestants.

After 130 years of horror, even the slow learners of Europe began to understand that no side had the power to defeat or kill all the others — though for each side this would have been the preferred course of action — so they had better figure out how to, at least, tolerate one another. This resulted in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, which introduced some limited ideas of religious tolerance.

The treaty involved great accomplishments by many people in advancing innovative ways of thinking by those who made the way for a new kind of peace. And, to be fair, such ideas began to arise fairly early in response to the bloodshed. Although Pope Paul III gave Imperial honours to the local grandee who raised the troops responsible for the Mérindol massacre; many in Europe were revolted.

One other factor must be noted, albeit briefly. As Luther was hammering his nails in northern Europe, in southern Europe, the Renaissance, which would change the perception of the human condition, had begun — and 130 years later, Renaissance thought fed into the ideas of tolerance in the Treaty of Westphalia. Even here, similarities are found: Much new Arab thought is bubbling beneath the surface, all too often suppressed by violence, just as the powers-that-were attempted to suppress early Renaissance thought. But, still, despite noble thought background to the Treaty of Westphalia, it was mainly blood exhaustion that led to the Peace.

Lessons from Western history

What are the lessons from this? The first is just attitudinal. Many in the West seem to believe that if only Arabs acted sensibly, like us, and were full of tolerance, like us, and had a nice intellectual Reformation, like us, then all their silly conflicts would disappear in rousing choruses of Kumbaya and John Lennon’s Imagine. This attitude adjustment creates a more realistic view of the Arab Spring and the very long sorting-out period that will follow.

Exhortations for tolerance, freedom and democracy from the rest of the world are only occasionally useful. They help at the margin and make it clear which side we are on — something that will be remembered if the Arab Spring produces a semblance of democracy and greater freedom. Still, people in the region will have to learn the lesson themselves, as did people in Europe, though much blood is likely to flow before that happens.

Is the Arab Spring akin to 1848?

We also need to be prepared for the up, downs and disappointments. Marx thought the revolutions of 1848 would bring Communist Utopia, but they were quickly defeated. Many compare 1848, “the Spring of Nations,” with the Arab Spring; but the Arab Spring, like the Reformation, contains a much broader, deeper and more existential range of issues. The immediate fires will not be as quickly extinguished as they were in 1848. But there is one hopeful lesson: The 1848 revolutions were crushed, but, within decades, a period of liberalization followed. This is a generational problem and opportunity. Young Arabs, brought up in an era of global communication, may be able to make their mark in 20 or so years just as the children of 1848 were.

A key for tolerance: Free markets

Arabs also have one great opportunity not available in the Reformation — the possibility of a reformed economy, and this is an area in which the West might be able to make a difference. This was not an option for the pre-industrial Reformation, ending more than 100 years before Adam Smith’s breakthrough understanding of the power of free markets.

Nations where democracy and freedom are imposed, but which lack institutions of tolerance, trust and self-expression, typically end up worse off. Democracy and freedom only flourish where these institutions exist. Free markets have generated the highest levels of prosperity in human history, and thus through prosperity promote the values institutions required for democratic evolution.

Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, two key figures in the World Values Survey, recently wrote in Foreign Affairs, “a massive body of evidence suggests … economic development does tend to bring important, roughly predictable, changes in society, culture and politics.… [H]igh levels of economic development tend to make people more tolerant and more trusting, bringing more emphasis on self-expression and participation in decision making.” In other words, commercial virtues and tolerance are mutually

supportive.

But, prosperity isn’t the full story — if it were, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait would be leaders in tolerance and democracy.

How prosperity is created is important. Free markets are based on economic freedom at the individual level — the ability of individuals to make their own economic choices. Economic freedom transforms the dynamics of any society that lacked it. When people make their own economic choices, they gain only when they produce products or services desired in free exchange — in other words, by making people better off. Those in other ethnic or sectarian groups become customers, suppliers and clients. Over time, this builds tolerance and a common sense of citizenship.

Crony capitalism is not the free market

Open markets matter because when governments — or government friends under crony capitalism — control the economy, the economy grows slowly or not at all. Individuals and groups battle one another for wealth and privilege. People gain by cultivating connections, suppressing the opportunities of others and making them worse off.

All too often, the individual gains, not as an individual, but as a member of a rent-seeking group, whether economic, ethnic or religious. Groups stand against groups, as is all too evident in much of the world. Without economic freedom, the biggest gains accrue to those who cut a bigger slice of the existing, limited pie for themselves to the disadvantage of others. That only exacerbates existing tensions.

With economic freedom, people who increase the size of the pie for everyone achieve the biggest gains. This is a key reason why empirical studies show that economic freedom promotes tolerance, democracy and other freedoms directly and indirectly through economic development.

But this is a hard sell in the Arab world. At a conference in Tunis last year, one of us was asked by a charming, well-educated economics professor at a local university why Tunisia should turn to “neo-liberalism” when it had been tried and failed there.

Neo-liberalism has become a pejorative for free markets, and Tunisia has tried nothing of the sort. For instance, U.S. Nobel Laureate economist Douglass North has called the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index the “best available” index of free markets. In 2010, just before the Arab Spring really got going, Tunisia rated 96th of the 141 jurisdictions rated — thus, no “neo-liberal” free market existed there.

The Arab world’s economy: often crony capitalism, not free markets

Many of the Arab dictators created klepto-crony capitalist states while telling their people that they were undertaking free-market reforms. Instead, they handed state assets to friends, relatives and allies who made money by suppressing free markets and gaining monopolists’ profits.

Given this mistaken notion of free markets, little support exists in the Arab world today for the concept. Additionally problematic, the Islamists’ priority is not economic, especially not liberalization, as they likely prefer state control of the economy since it increases a regime’s power over the economy and, thus, people’s lives. Many secularists in the Arab world tend to be leftist. For example, in Tunisia, leftist secularists have suffered assassination while left-wing unions have rallied to their cause.

Also problematic, the shadow of “pan-Arab socialism” hangs over the region. Economies are heavily controlled by the state, para-state organizations, like the military, and government cronies, with bloated public sectors. According to the World Bank, between 1980 and 2010, MENA (Middle East and Northern Africa) was the region with the world’s weakest growth at about 0.5 percent annually, half the rate of sub-Saharan Africa and one-ninth the rate of Asia. With low prosperity and weak economic freedom associated with low tolerance, no wonder the Arab Spring is bloody and likely to continue to be bloody.

Limited government and limited Western aims

The West cannot force factions in the Arab world to not hate or kill one another (imagine a Turkish force invading Reformation Europe to keep Christian factions apart). We mostly cannot impose democracy or bomb people into peace (both mostly oxymoronic concepts, though possible in rare cases.).

However, given the success of free-market economies, nations that are advanced economically may be able to help by combatting the mistaken identity of crony capitalism for free markets and by encouraging reform. That includes dismantling crony capitalist networks and monopolies, removing trade barriers, reducing state control of the economy, massively downsizing the civil service, eliminating market-distorting subsidies and creating a broad tax base that does not favour the powerful and rich. Such reforms will produce resistance; they extinguish privileges for those who expect them. The road is difficult, but affluent nations can help with economic support, and such reforms will alleviate other even deeper problems by changing societal dynamics.

Mark Twain (among others) has been credited with saying “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” The Arab Spring is not a repetition of the Reformation, but there are plenty of rhymes. They point to the lengthy timeframe and the understanding that we will have very little effect on the immediate dynamics, but that we can help promote change in the nature of the dynamics themselves by promoting freer and more open economies.

Fred McMahon is Michael Walker Chair of Economic Freedom Research with the Fraser Institute; Mark Milke is a senior fellow with the Fraser Institute.