Concentrated feeding animal operations — more commonly referred to as factory farms — first began to appear around the 1920s. Industrialization was speeding up everything from transportation to communication, while, at the same time, medical discoveries such as insulin and penicillin were dramatically improving the quality of human and animal health. Farmers realized they could raise animals indoors in small spaces with little or no sunlight as long as they fed livestock Vitamin D and antibiotics. In addition, long-distance transportation enabled shipping of animals to larger, more centralized slaughter operations.

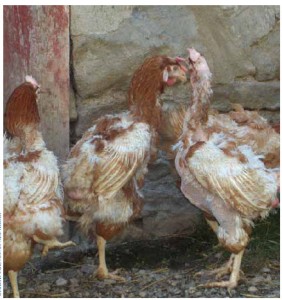

It wasn’t until after the Second World War, however, that factory farms became more widespread. By the 1980s, they had become commonplace, and with them the confines of battery cages for laying hens, gestation crates for breeding pigs, feedlots for beef cattle and tethered stalls for dairy cows.

Today, about 95 percent of the animals raised for food live in these kinds of conditions, under manufacturing ideals applied effectively to furniture and car parts, but less so to cows and pigs. While efforts are under way in various countries, most notably the European Union, to improve conditions, the seemingly insatiable global appetite for meat is calling into question not only our eating habits, but our ability to sustain them in a humane way. According to the Washington, D.C.-based Worldwatch Institute, meat production globally has tripled over the last four decades and increased 20 percent in the last 10 years, with emerging middle classes in countries such as China helping to drive this demand. In Canada alone, looking at pork as an example (it is the world’s most consumed meat), figures from the Canadian Pork Council show that the number of pigs raised in Canada nearly doubled between 1984 and 2012.

Canada, similar to the EU, is working to phase out what could loosely be termed extreme factory farming. Countries such as China, meanwhile, are embracing it. This is farming that controls every aspect of the animal’s life, denying it most of its natural behaviour and, in many cases, altering it physically, usually without pain relief.

Egg-laying hens, for instance, have up to a third of their beaks cut off — “trimmed” — to minimize the cannibalism that results from pecking in battery cages.

Pigs have their tails docked, leaving only an ultra-sensitive stub, to prevent tail-sucking of pen mates that may cause infection.

Piglets’ teeth are clipped to minimize injury to their mothers’ teats. Normally the nursing sow would get up and walk away — exercise for both the sow and piglets. Confined on her side in a farrowing crate, she can’t move.

Male piglets are castrated, without anesthetic, to prevent “boar taint,” an odour and flavour that can make pork unmarketable.

Dehorning beef cows, tusk-trimming boars and tail-docking dairy cows are also procedures that have evolved into more or less routine practices, as have confining the animals and feeding them additives to accelerate growth and combat unsanitary living conditions.

Factory farming also has spawned systemic mass disposal of animals and waste that is both a welfare and environmental concern. Many male chicks in egg hatcheries are ground up alive and used as fertilizer. Bull calves on dairy farms, considered an industry byproduct, are taken from their mothers and sold as veal. Piglets that don’t meet aggressive growth timelines are euthanized by “pounding against concrete,” where the animal is held by its back legs and pounded against concrete flooring. High concentrations of urine and fecal waste in these facilities cause respiratory problems, both for workers and animals, and leech into water systems, killing aquatic life.

The EU is taking a leadership position in improving these systems. It has banned battery cages for egg-laying hens and greatly reduced the allowable time sows can spend in stalls. Its ban on castration of pigs takes effect in 2018. Several individual EU member states — Sweden and Norway, for example — have imposed bans on practices such as beak trimming. There are also provisions for the use of straw or similar substrate for pigs, an often-overlooked issue in Canada, but important considering pigs’ strong nest-building instincts. Research from scientists on Canada’s National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) shows that, among other things, straw reduces “stereotypies” — neurotic, repetitive behaviour including tail-biting.

Admittedly, there are problems in the EU with compliance with the regulations, as well as concerns regarding producer competitiveness. Farmers in countries that are complying with the ban — Britain, for instance — are understandably upset about pork imported from non-compliant countries. Bottom line: Better animal welfare usually costs money, which drives up production costs. Here in Canada, the Canadian Pork Council estimates that conversion of two-by-seven-foot sow stalls to open housing will average $500 per pig, though this estimate is disputed as inflated.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise, then, that compliance is promising to be an issue in Canada, too. In the NFACC’s newly updated code of practice for pigs, confinement of sows in stalls has been reduced from four months (the sow’s entire pregnancy) to five weeks. (As an aside, this is in addition to the three weeks she will spend in a farrowing crate, a different cage where she is moved to give birth and nurse her piglets.) The EU has similar allowances for sow stalls: they are permitted for four weeks after insemination and one week before farrowing.

Canada’s new sow-stall requirements, one of several contentious areas in the new pig code, will begin taking effect in 2014. However, given that it’s voluntary, some pork associations are considering non-support of the code and, instead, creating their own.

Edana Brown is a director of the Canadian Coalition for Farm Animals.