Sustaining sub-Saharan Africa’s current welcome prosperity, especially an average annual GDP growth of five percent, will demand enhanced or better political leadership, improvements in prevailing methods of governance, a canny embrace of Chinese mercantilism and the ability to cope successfully with or effectively manage the many serious problems — demographics, energy shortfalls, paucities of educational opportunity, scarcity of water and new and old diseases — that threaten to halt or marginalize the continent’s progress.

The future of the 49 very distinct countries of sub-Saharan Africa is at a critical inflection point. If China itself, on the back of North American and European consumer purchases and domestic demand, continues to grow annually at nearly eight percent a year, African countries will be able to continue very profitably to export their petroleum, natural gas and base minerals across the high seas to Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong and Chengdu. As long as China wants more and more of Africa’s natural resources, Africa’s people (and especially its elites) will benefit and their living standards will eke upwards. But Africa must also learn to manage China.

China and Africa

Global commodity prices, which are fuelling Africa’s GDP growth averages, are driven largely by Chinese demand. Propelled by the same impulses, offshore and onshore, Africa is being explored and, over time, exploited. Countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, Ghana and Chad have recently joined the known energy exporters of Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea and the Sudan, but this important momentum depends on China’s relentless appetite.

So does the infrastructural boom that is now benefiting Africa. China is building roads, railways, schools, hospitals, party headquarters, stadiums, and almost anything else the African leaders with whom China co-operates want. It is also building dams for hydropower in dozens of countries despite the fervent protestations of environmentalists. As former British prime minister Tony Blair has said: “if a country in Africa wants something done, such as building a road, they go to the [Western] donor community and it ends up…[mired] in months of bureaucracy. If you tell the Chinese you want a road, the next day someone is out there with a shovel.” By 2013, Chinese operatives controlled about 40 percent of the sub-Saharan African construction market.

Not all Chinese projects turn out well; there are many shoddy examples that have had to be re-done or abandoned. The Chinese have also been slow to employ Africans, even as manual labourers, preferring Chinese workers imported from home. China has also been reluctant to transfer technology along with a completed edifice or transportation improvement. Mining management and supervision of road building are all controlled by Chinese; Africans are not allowed to handle the wheels of real power. The Chinese attitude almost everywhere seems to focus on getting a job done, even if they need to use sharp elbows along the way.

These and similar attitudes have not endeared China to African workers. African consumers sometimes complain about cheap goods that fall apart. And African traders, like the chicken sellers in Lusaka’s central market, moan that Chinese traders get up earlier and import less expensive chickens from China, thus gaining unfair advantage in the battle for consumer attention.

China naturally curries favour with those who rule, and does so bilaterally rather than through multilateral African consortia. That means that it ends up working hand in glove with petroleum-controlling autocrats, such as those in Angola or the Sudan, or with a tyrant such as President Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, who controls diamonds, ferrochrome, platinum and more. China has also supplied weapons and ammunition that predators such as those in the Sudan have used to attack civilians in the Blue Nile, South Kordofan and Darfur districts of the Sudan. It is alleged to have assisted Mugabe in rigging the last election in Zimbabwe and shoring up the merciless regime in Equatorial Guinea.

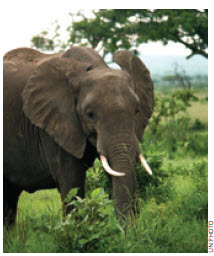

Chinese nationals, but not necessarily the Chinese government, are also responsible for fuelling a great spike in the poaching of elephants for their tusks and rhinoceroses for their horns since 2007. Fully 70 percent of global demand for these illicit products is Chinese and Chinese entrepreneurs and syndicates are known to employ African gangs to do their bidding against the continent’s dwindling herds of elephants and rhinoceroses.

The demographic challenge

Africa is exploding. Half of all those born in the world from now until 2050 will be Africans. Sub-Saharan Africa is growing in population faster than any other part of the world, despite the heavy presence of HIV/AIDS, malaria, antibiotic resistant tuberculosis, diarrhea and many other ailments, drunk drivers and high rates of infant and maternal mortality. Add to this result the intensifying civil conflicts in the Central African Republic, the Congo, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan and the Sudan.

African fertility exceeds that of every other section of the globe. African families are larger, with more dependent children. Family median age is younger. At mid-century, Africa is predicted to have by far the globe’s youngest population, with more than half of all African countries filled by the new youth bulge.

If the increase in the population of the planet follows the extrapolations of the UN Population Division, in 2100 there will be 4.6 billion Asians and 3.7 billion Africans, an enormous increase of Africans.

Nigeria, today with 162 million — Africa’s largest country and the seventh largest nation in the world — will swell in 2100 to 730 million and become the third largest polity in the world after India and China. The United States at 478 million will follow. Fifth in this new order will be Tanzania, a mere 45 million now but forecast by the UN to include 316 million people in 2100. Pakistan and Indonesia will be next and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, now holding 66 million and many killing fields, will increase in 2100 to 212 million and become the globe’s eighth largest entity. Little Malawi is expected to grow from 13 million to 130 million and Kenya from 40 million to 160 million.

Lagos and Kinshasa will soon be larger (and more congested) than Cairo. Canada’s entire population could soon fit into just these two cities. A congested place like Rwanda will have 987 persons per square kilometre, up from 403 today; it will soon be more crowded than Japan, on average. Overall, Africa’s population will shortly become more than 50 percent urbanized and, before long, 75 percent of its people will live in cities.

The central question facing Africa and its leaders is whether this population explosion will become a demographic dividend, as it did in Southeast Asia in the 1980s, or whether it will produce a demographic disaster of a cataclysmic nature. Will Africa’s political leaders and governance structures respond well to these new population pressures? Will Africa be able to feed itself? Will there be enough water, a robust enough infrastructure, sufficient electrical power, and much else, to meet the needs of these new numbers of city dwellers? Already Lagos and Kinshasa are very difficult to manage and supply. And will governments be able to keep their city residents secure and safe?

Governance and leadership

The answers to all of these questions, and to taking the best advantage of Chinese resource appetites, depends on the extent to which the countries of sub-Saharan Africa can strengthen the way they perform as governments and improve the way their political masters lead.

As Tony Blair has said, “The biggest obstacle to Africa’s development is governance.” Only by delivering to citizens the key political goods (collectively governance) of security and safety, rule of law and transparency, political participation, economic development and human development (education and health), can the nations of Africa catch up with Asia, attract investment, cope with severe demographic challenges, educate their multitudes and provide the peace and stability their increasingly middle-class populations desperately demand.

Today, only a handful of governments uplift their peoples by providing good governance. Instead, the majority, such as the misnamed Democratic Republic of Congo, enrich their elites, prey on their own citizens, ignore the delivery of health and educational services and allow inflation and corruption to increase exponentially.

Contemporary sub-Saharan Africa has three kinds of governments: a clearly well-performing set of a dozen or so, a middle group of about two dozen that are trying to climb up the governance rankings and a desperately ill-governed rabble of another dozen or more that do very little to meet the aspirations of their people. At the top are Mauritius, Cape Verde, Botswana, the Seychelles, South Africa, Namibia,Ghana, Lesotho, Tanzania, São Tomé and Principe, Zambia and Benin. These are mostly literate places that adhere to the rule of law, hold regular elections, are growing economically and offer relatively high standards of medical care. They are secure and, except for South Africa, comparatively safe countries. A few of them, primarily the top four, are remarkably free of corruption.

The special ingredient in each of these well-governed sub-Saharan African states has been visionary, responsible leadership. It has invigorated and ensured high-quality governance and created a political culture — a value system — that has enabled strong political institutions to be implanted, to grow and to flourish. That combination of committed leadership, democratic political cultures and solid institutions has provided the foundation and strengthened good governance. It has, in turn, led to exemplary economic performance, rising standards of living (in the cases of Botswana and Mauritius over four decades) and large degrees of citizen satisfaction.

Some of the middle-ranking countries in the list are catching up with the top performers precisely because they are better led than ever before. Liberia has jumped a number of places in the rankings, as have Malawi and Rwanda. And better leadership accounts for Tanzania and Zambia’s arrival in the charmed top-governance performance circle.

To transform the worst of the worst — the Sudans, Chads, Central African Republics, Zimbabwes, and even Nigerias — of Africa into countries that deliver reasonable attributes of governance (and therefore improved livelihoods) to their citizens, these countries need leaders who devote themselves to national needs rather than to clan, lineage or personal enrichment. Only when such responsible and effective rulers are recruited or vaulted to power by a newly emboldened middle class will those spaces where lamentable governance and internecine conflict are the norm begin to deliver key political goods to their peoples. Making such transitions happen is a task mostly for Africans themselves, but the United Nations, the African Union, and like-minded donors can nudge and assist by strengthening leadership capacity and building or rebuilding structures of good governance.

Sometimes, too, as in Mali and Somalia, outside intervention is required to save a democracy from succumbing to terror, or to prevent unusually high levels of human suffering caused by bad leadership and the absence of good governance. But those instances will continue to be exceptional. Africa must continue to nurture its own better leaders and to pay ever closer attention to improving governance.

Robert I. Rotberg is Fulbright Research Professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University and a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation.