The political crisis that led to the downfall of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych stemmed from Ukraine’s inability to make a permanent transition to a stable democracy since it became independent in 1991. To understand this difficulty, we must examine three factors: Ukraine’s history, the role of the EU and the influence of Russia.

The transition from authoritarianism to democracy is difficult. As the history of most Central and Southern European countries in the 20th Century illustrates, many countries that try democracy for the first time fall back at least once into dictatorship.

The Burden of Ukrainian History

Compared with the countries in Central Europe that achieved independence about the same time, for several reasons, Ukraine has been hampered in achieving a stable democracy:

• Ukraine was only obliquely affected by the gradual evolution of Western Europe from authoritarianism to pluralism;

• It had no tradition of the separation of powers nor the rule of law;

• Ukraine had no previous experience as an independent state, to give it a sense of national identity and cohesion;

• It also lacked much of the apparatus of a state;

• It had never experienced democracy;

• It had no knowledge of a market economy.

Two other factors have influenced Ukraine’s democratic prospects — the EU and Russia. Unlike the states of Central Europe and the Balkans, Ukraine did not, after the fall of communism, receive an offer of EU membership and Ukraine has, at times, faced severe pressure from Russia seeking to block Ukraine’s move towards democracy and the West, and to force it into Russia’s economy and security organizations.

The role of the EU

The EU’s relationship with Ukraine has been one of missed opportunities. Successive Ukrainian governments have sought membership in the EU. In the opinion of many observers, an earlier offer of EU membership could have totally changed the political landscape in Ukraine by producing a consensus among all major parties in favour of democracy.

In 2004, the EU did introduce the European Neighbourhood Policy for the EU’s eastern and southern neighbours such as Ukraine. This policy was, however, intended to spread democracy and free markets without offering membership. The policy was proposed to the democratic government that emerged from the Orange Revolution, that of Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. The Ukrainians were not enthused by the idea because there was no membership offer and the amount of assistance proposed was inadequate.

The EU, having missed the boat with Yushchenko, a democrat, then offered in 2010 a more generous association and free-trade agreement to his successor, the thuggish Viktor Yanukovych. The proposed association agreement hinted at eventual EU membership, but still was stingy in its offer of financial assistance.

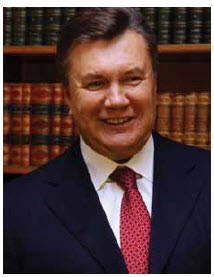

The policies of Yanukovych

In reaction to the incompetence of Yushchenko and Tymoshenko, Ukraine followed the past pattern of many other European states by, in the 2010 presidential elections, choosing the dictatorial Yanukovych. President Yanukovych pursued two major goals — to enrich himself and his family through corruption and to remain in power through repression.

Nevertheless, Yanukovych accepted the EU’s offer of an association agreement, and the EU’s conditions of political and economic reform.

Yanukovych believed the EU’s conditions were not serious and furthermore, expected that the IMF would relax its requirement for economic reforms in return for a loan of $14.3 billion. He therefore continued his policy of repression and ignored economic reform. He did away with the rule of law. He threw his chief rival, Tymoshenko, and others of her party, in jail. He hobbled the media, harassed the opposition, fixed elections and neutralized parliament.

In consequence, since the EU maintained its conditions, Yanukovych announced on Nov. 21, 2013 that Ukraine would not sign the association agreement.

However, Ukraine’s refusal to comply with the IMF’s terms left the country in imminent danger of a currency collapse and sovereign default. If the money could not come from the West, Russia was the alternative. To understand the significance of this shift, we must turn to Russian policy towards Ukraine since its independence.

Russian policy towards Ukraine

Relations between successor states to a vanished empire often remain unsettled for a long period after the breakup. What makes the Russian-Ukrainian relationship especially difficult are three factors.

The current Russian leadership apparently refuses to accept the reality of Ukrainian independence. Putin has repeatedly described the Russians and Ukrainians as one people. He has also stated that Ukraine’s independence in 1991 was a mistake.

Moscow regarded the coloured revolutions that, from 2003 to 2005, shook Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and especially Ukraine as the result of Western plots. Moreover, the revolutions raised the spectre of a democratic revolution in Russia.

Following the admission of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to NATO and the EU in 2004, Moscow also considered the attempt by repeated Ukrainian governments to join NATO and the EU, was the result of a Western attempt to weaken Russia. Putin reportedly told Bush at the NATO Bucharest Summit in 2008 that Ukraine was “not a real nation,” that much of its territory had been “given away.” He warned Bush that if NATO put Ukraine on the path to membership, Russia might instigate the partition of Ukraine.

When it appeared likely last August that the Ukraine would sign the EU Association Agreement, Russia temporarily blocked the import of all Ukrainian goods. In September, Putin’s point man on Ukraine, Sergey Glazyev, stated that Ukraine could expect worse if it went ahead with the EU Agreement. Glazyev also stated that if Ukraine signed the association agreement, Russia could possibly intervene if pro-Russian regions of the country appealed to Moscow.

In turning to Russia, instead of the IMF on 17 December, Yanukovych received the promise of the 15 billion Euros he sought in order to avoid bankruptcy. In return, however, he had to surrender a substantial part of Ukrainian sovereignty. In particular, vast sectors of the Ukrainian economy were to come under joint control. Ukrainian customs regulations were to be aligned with those of Russia’s Customs Union. Trade agreements with anyone else would require Russian approval.

Bringing Ukraine back into Russia’s orbit through Ukrainian membership in Russia’s planned Eurasiasn Economic Union (to replace the existing Customs Union next year) and the Common Security Treaty Organization would be highly advantageous to Russia. It would in Russia’s estimation, make a success of the two organizations. It would also give Russia control of Ukraine’s international economic policy and its defence policy.

Prospects for Stable Democracy after Yanukovych

What began as a simple demonstration on the Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square in Kyiv, by students against the refusal of President Yanukovych to sign the EU Association Agreement, grew and multiplied with each attempt at suppression until demonstrations were occurring in most of Western and Central Ukraine. The Maidan demonstration survived, at the cost of 88 lives, the final brutal assaults ending in February by the security forces. Then, Yanukovych’s parliamentary supporters turned against him, and his security guards deserted him, leading to his flight from Kyiv on Feb. 21.

The overthrow of Yanukovych is an event comparable to the Orange Revolution of 2004. If the new government is allowed to survive, it gives Ukraine a second chance to accomplish what the victors of that revolution failed to do — namely, establish a stable democracy.

The first steps of the new government have unfortunately been exploited by Putin to justify efforts to destabilize, or break up Ukraine. The flight of Yanukovych without having signed into law the elements of the compromise agreed to with the opposition, forced parliament, so as to allow the government to proceed, to pass a series of decrees, notably relieving the president of his powers, and choosing an interim president and prime minister. The High Administrative Court has rejected a challenge to the legality of parliament’s actions.

Nevertheless, Putin has maintained his position that the new Ukrainian government is illegitimate. He has refused to deal with it and he refuses to recognize the early presidential elections on 25 May. Instead he has announced his support for the return to power of President Yanukovych for the purpose of making Ukraine into a federation with the states enjoying responsibility for foreign policy, an arrangement that would give Russia de facto control of certain parts of the country.

Certain initiatives of the new constellation of forces have especially aroused the opposition if not the fear of the people in Yanukovych’s heartland — South-Eastern Ukraine — since they seemed to confirm Russian propaganda that the new government was the result of an anti-Russian neo-Nazi coup:

Prime Minister Yatseniuk’s coalition cabinet apparently included only one minister from Eastern Ukraine;

Although the government is, in the main, centrist, out of eighteen ministers, it has three from the rightist party, Svoboda;

The Ukrainian parliament cancelled a law passed under President Yanukovych allowing Russian to be used as an official language in areas with a large Russian-speaking population. The new law was, however, vetoed by interim President Turchynov.

Parliament’s abrogation of the language law nevertheless provided the excuse for President Putin to equip himself with the legislative authority to invade Ukraine in support of supposedly oppressed Russian speakers.

In view of Russia’s repeated warnings that it might promote the secession of parts of Ukraine if Ukraine decided to align itself with the West, the Russian takeover of Crimea should have come as no surprise.

The annexation of Crimea may prelude further Russian attempts at annexation and destabilization. In his March speech on the occasion of the annexation of Crimea, Putin implied that those in the Russian-speaking South-East of Ukraine should also join Russia. He declared Russia’s guarantee of Ukraine’s further stability and territorial integrity depended on Ukraine ensuring that the rights and interests of Russian speakers were fully respected. To stir up trouble, Russia has repeatedly sent agitators over the border into the cities in the Russian-speaking areas. In late March, the White House warned Russian troops may be massing for an invasion of Ukraine.

President Putin has a strong motive to destabilize Ukraine further. Ukraine’s signing the EU’s association agreement in March, if allowed to stand, would end Russia’s hope of bringing Ukraine into Russia’s customs union. On the same day, Russia imposed a total boycott on Ukrainian goods.

If Ukraine’s second attempt at democracy is to succeed, therefore, an extraordinary amount of Western economic and political support will be needed. In the face of the Russian trade boycott on Ukrainian exports, the economic support that the West has so far promised Ukraine, may be insufficient. And in view of the danger of Russia attacking the Ukrainian mainland, the West is right to threaten substantially increased sanctions in such a case.

The burden we would bear would be considerable, should Russia try again to annex parts of Ukraine. Then we could be faced with a general Russian war with Ukraine, the mass movement of refugees and a shift in the balance of power in Europe.

For the long run, we have to recognize that Ukraine can only be secure if its independence is accepted by Russia. Henry Kissinger has suggested a neutral status for Ukraine similar to that of Finland during the Cold War.

• Ukraine would have the right to choose freely its economic and political associations;

• Ukraine would not join NATO;

• Ukraine should be free to create any government compatible with the expressed will of its people;

• Russia would recognize Ukraine’s sovereignty over Crimea in return for increased Crimean autonomy and a renewed guarantee of Russia’s naval base.

For the Russians to accept Ukraine‘s neutrality, it should be embedded in a wider East-West rapprochement. The EU might actively pursue Catherine Ashton’s declared willingness to negotiate a common economic space with Russia’s Customs Union in return for a guarantee by Russia of the right of countries such as Ukraine to remain outside of the union. In addition, the EU might amend the association agreement so as to allow Ukraine to have free trade with the EU and Russia’s Customs Union.

Derek Fraser is an associate fellow at the Centre for Global Studies and adjunct professor for political science at the University of Victoria. He was posted to Ukraine as ambassador from 1998 – 2001.