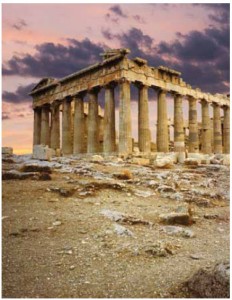

As I write this, Greece remains the poor boy of the European Union and democracy teeters drunkenly in various places around the world. These facts draw me to remember the Parthenon in Athens — these plus Joan Breton Connelly’s new book, The Parthenon Enigma: A New Understanding of the World’s Most Iconic Building and the People Who Made It (Random House of Canada, $40). When architects and architectural historians speak of the Greek Revival style (picture the British Museum, say, or the New York Stock Exchange building), it is ultimately, or largely, the Parthenon, with its stunning proportionality and dignity, that is being paid tribute. Without doubt, the Parthenon, sitting atop the Acropolis in Athens, is one of the world’s most famous and most influential structures.

It was built in the middle of the 5th Century BCE by the Greek leader Pericles. Leader as much as ruler perhaps, because the essence of the Greeks’ democracy was that although a certain number of officials were elected to office, the majority were chosen by lottery (an idea that lingers in our own still-breathing version of democracy only in the way juries are selected).

When the Enlightenment was in full bloom and the study of ancient Hellenic culture mushroomed, everyone seemed to understand why the great temple was constructed: to honour Athena, the ancient goddess of war, justice and civilisation itself. Running round the whole circumference of the building, shaded by protruding cornices, was a bas-relief frieze that appeared to depict the Panathenaic festival, celebrated every four years to commemorate Athena’s birth. The narrative sculptures ran 160 metres, like a giant marble storyboard, showing a parade of warriors, maidens, musicians, animals and so on.

As the centuries rolled on, this interpretation remained in force, though the building itself underwent many abuses and the stone narrative lost some of its continuity. At one point, the Parthenon became a Christian church; at another, a mosque. In the 17th Century, the Turks used it to store gunpowder and the Venetians bombarded it with cannon fire. Travellers engaging in the Grand Tour carried off bits as souvenirs.

Then came Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin. Between 1799 and 1803, when he was British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, he bankrupted himself buying large portions of the frieze, which he later had to sell at a loss to the British Museum, where, controversially, they remain. Other portions are in curatorial custody in Paris and Rome, but the Elgin Marbles in London, 75 metres of them, are the most important, partly because they include the section from the east side of the Parthenon over the main entrance. The scene was long thought to show (in fact, still is thought by most scholars to show) two adult figures, male and female, handing out robes to young celebrants. This is where Dr. Connelly comes in.

She is a classical archeologist and a MacArthur Fellow who teaches at New York University. In publishing The Parthenon Enigma, she has upset the unanimity of that judgment. To put the matter very briefly, The Parthenon Enigma argues that the purpose of the Parthenon was not simply to brag about democracy by showing the Panathenaic procession and thus depicting a part of Athenian daily life at the time. As she said to me over the phone when I called to interview her for Diplomat, “No Greek temple” — the Parthenon used to be merely the centrepiece of a large congregation of temples on the Acropolis — “shows anything taking place in what was the present moment.” Rather, she believes that the male figure is King Erechtheus of legend and the female one is his queen, the priestess Praxithea, and that they are giving their children shrouds rather than robes. For the legend tells of how the Delphic Oracle told Erechtheus that one of his three daughters must be sacrificed to prevent the city from being overrun by enemies (whereupon, the tale continues, the two other sisters took their own lives in a show of solidarity). In Dr. Connelly’s interpretation, this piece of the frieze was intended to honour the spirit of sacrifice that was another essential part of the larger abstraction of Greek democracy. “The public needed protection,” she explained, “and one had to give to the civic good” even if that meant sacrificing one’s life for the safety of the city-state. Not even kings, queens and princesses were exempt.

She is a classical archeologist and a MacArthur Fellow who teaches at New York University. In publishing The Parthenon Enigma, she has upset the unanimity of that judgment. To put the matter very briefly, The Parthenon Enigma argues that the purpose of the Parthenon was not simply to brag about democracy by showing the Panathenaic procession and thus depicting a part of Athenian daily life at the time. As she said to me over the phone when I called to interview her for Diplomat, “No Greek temple” — the Parthenon used to be merely the centrepiece of a large congregation of temples on the Acropolis — “shows anything taking place in what was the present moment.” Rather, she believes that the male figure is King Erechtheus of legend and the female one is his queen, the priestess Praxithea, and that they are giving their children shrouds rather than robes. For the legend tells of how the Delphic Oracle told Erechtheus that one of his three daughters must be sacrificed to prevent the city from being overrun by enemies (whereupon, the tale continues, the two other sisters took their own lives in a show of solidarity). In Dr. Connelly’s interpretation, this piece of the frieze was intended to honour the spirit of sacrifice that was another essential part of the larger abstraction of Greek democracy. “The public needed protection,” she explained, “and one had to give to the civic good” even if that meant sacrificing one’s life for the safety of the city-state. Not even kings, queens and princesses were exempt.

Her theory came about only after a long gestation. “Starting in the 1960s,” she went on, “the study of ancient Greek religion was burgeoning, but it was viewed more as politics than as actual religion.” It was during this decade that she learned of a certain mummy dating to the era when Egypt was under the rule of Greeks (Alexander the Great, Ptolemy and so on). The mummy had been in the Oxford University collection for generations. When unwrapped, it was found to contain a fragment of manuscript by the playwright Euripides, who was writing very close to the time when the Parthenon was built. Specialists in Paris were able to separate the manuscript intact from the cloth to which it had become affixed. This fragment, 125 lines, was part of an otherwise unknown text dealing with a Greek priestess who had three daughters whose lives she sacrificed to save her culture from invasion and ruin. No coincidence, says Dr. Connelly.

Her theory came about only after a long gestation. “Starting in the 1960s,” she went on, “the study of ancient Greek religion was burgeoning, but it was viewed more as politics than as actual religion.” It was during this decade that she learned of a certain mummy dating to the era when Egypt was under the rule of Greeks (Alexander the Great, Ptolemy and so on). The mummy had been in the Oxford University collection for generations. When unwrapped, it was found to contain a fragment of manuscript by the playwright Euripides, who was writing very close to the time when the Parthenon was built. Specialists in Paris were able to separate the manuscript intact from the cloth to which it had become affixed. This fragment, 125 lines, was part of an otherwise unknown text dealing with a Greek priestess who had three daughters whose lives she sacrificed to save her culture from invasion and ruin. No coincidence, says Dr. Connelly.

“Today, the idea of the ultimate sacrifice is something we associate with military life, not necessarily with civilian life, at least not in the same way or to the same degree,” she told me. But this piece of manuscript was something different. In ancient cultures generally, there was little if any distinction between mythology and history, if indeed they were not downright inseparable. But Dr. Connelly thought she detected a true story in this little scrap of Euripides’ work. All the more so, in fact, because Euripides, though he dealt with gods and mythical figures as did the other ancient dramatists, portrayed them in a much more realistic way, as though he were using his characters to describe the life around him.

There’s some potential irony here because it’s possible that this key piece of the frieze could well have vanished through war or neglect if not for Lord Elgin, whose acquisitiveness a great many people, Greeks most of all, consider hideous kleptomania and downright cultural imperialism. Dr. Connelly says that he can’t fairly “be judged by the behavioural standards of our own time, though reading Lady Elgin’s letters on the subject—‘I took three heads today’—is an appalling experience.” Dr. Connelly, of course, favours the marbles’ return to Greece so that what she considers the greatest surviving work of art from the ancient world can be reconstituted.

There’s some potential irony here because it’s possible that this key piece of the frieze could well have vanished through war or neglect if not for Lord Elgin, whose acquisitiveness a great many people, Greeks most of all, consider hideous kleptomania and downright cultural imperialism. Dr. Connelly says that he can’t fairly “be judged by the behavioural standards of our own time, though reading Lady Elgin’s letters on the subject—‘I took three heads today’—is an appalling experience.” Dr. Connelly, of course, favours the marbles’ return to Greece so that what she considers the greatest surviving work of art from the ancient world can be reconstituted.

The story of the Elgin Marbles and the British vogue for gobbling up ancient Hellenic art and bric-a-brac is told in another new work, Delphi, A History of the Center of the Ancient World (Princeton University Press, US$29.95) by Michael Scott, a classical archeologist widely known through his television documentaries. As for Dr. Connelly, she first went public with her conclusion about the frieze in a paper published in the American Journal of Archeology in 1996. “The article was highly controversial,” she explained. “It had its followers, but few people in the field changed their minds. Elder scholars in particular found my work hard to embrace.” She continued to pursue her idea through a number of avenues. One result was her book, Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece (Princeton, US$39.95). It argues that priestesses in particular, and women generally, played an even greater role in Athens and the other Greek city-states than has been supposed, especially in religious matters, and certainly were never second-class Athenian citizens (except, of course, in the sense that they didn’t vote).

As for The Parthenon Enigma, an exceptionally elegant piece of prose, it deals with far more than just the enigma of the title. Dr. Connelly discusses everything from the geology of the Acropolis itself to how, by exuberant degrees, the Parthenon became such a universally recognised landmark — the logo of a civilisation, one might almost say. Today it is held together by titanium rods, which replaced the steel reinforcements installed in the 1920s and 1930s. A bit ragged round the collar and cuffs, to be sure, but a magnificent thing in and of itself. I’ve seen it only once. I was rushing through Athens, which was on fire at the time and full of troops and protesters, and I glanced up to see the great building illuminated with a warm yellow glow, as though flaunting its permanence and mocking the human affairs getting out of control down below.

A Canadian footnote. As governor general of what was then (1848–49) the Province of Canada, James Bruce, the eighth Lord Elgin, son of the dastardly collector, was a key figure in bringing about responsible government. But his decision to compensate francophones for losses incurred in the Rebellions of 1837–38 caused an anglophone mob to attack Parliament in Montreal and burn it to the ground. He later became high commissioner to China where he considered destroying the Forbidden City, but settled for stripping the art treasures from the Old Summer Palace and then setting the vast complex on fire.

VERY BRIEFLY, OTHER NEW BOOKS

What a surprise to find in Ali A. Allawi’s book, Faisal I of Iraq (Yale University Press, US$40) that the co-founder of the Iraqi state was just as cunning, wise and charming as he was portrayed to have been by Alec Guinness in Sir David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia. With help from Gertrude Bell, Winston Churchill, T.E. Lawrence and others, Faisal (1885–1933) was only the second person to free a Middle Eastern country from European colonialism (both British and French) — Egypt having become a republic previously. He was a nation-builder in every sense and a great proponent of Jews and Arabs living together peacefully. The author is an exiled Iraqi cabinet minister. By contrast, Zaid Al-Ali, a constitutional lawyer, shows, as though we needed reminding, what became of the dream in The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy (Yale, US$35).

Robert D. Kaplan’s works on geopolitics have been mentioned in these pages several times. His new book, Asia’s Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific (Random House of Canada, $31), coolly analyses the growing entanglement of a waxing China and a waning United States, not to mention the added uncertainties that Taiwan, Japan and the two Koreas have regarding the superpowers and one another. Mr. Kaplan does so with his characteristic thoughtfulness and readability, though, to my ears at least, there is always the thwrap-thwrap sound of black helicopters in the background. He sat on the Pentagon’s defence policy board, works for a private global intelligence firm and is a senior fellow at one of those American think-tanks that are so much scarier than Canada’s own more economically focused ones. (See Thomas Medvetz’s Think Tanks in America — University of Chicago Press, US$25 paper — the most thorough, detailed and up-to-date survey of this nebulous world of so-called policy institutes.)

The sour relationship between Japan and China in particular concerns much more than arguments over small disputed islands. China has never forgotten or forgiven the Japanese invasion of the 1930s, which began with the grabbing of Manchuria, then called Manchukuo. Glorify the Empire: Japanese Avant-Garde Propaganda in Manchukuo by Annika A. Culver (UBC Press, $32.95 paper) tells how Japan tried to make itself seem attractive to those it overpowered by using graphics that emphasized how modern and contemporary Japanese society was. Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan’s Sex Slaves by Peipei Qiu and others (UBC Press, $32.95 paper) includes often gruesome first-hand accounts of how the Japanese army forced Chinese women to become prostitutes — a subject still being argued about loudly in both countries today.

All readers of the Economist will have noticed the unsigned political column titled “Bagehot” — most of them, one imagines, without catching the reference. The feature is named in honour of Walter Bagehot (1826–77), the long-serving editor of the paper (the Economist, though a weekly magazine, always refers to itself as a newspaper, which it hasn’t actually been for generations). He stamped his prose and everything else with his own zesty brand of 19th Century liberalism, suspicious of both intractable conservatives and radical reformers. His Collected Works embraced 15 volumes but he never wrote an autobiography or even a memoir. Now comes Frank Prochaska, an American historian cross-appointed to Yale and Oxford, who has written The Memoirs of Walter Bagehot (Yale, US$35), mimicking the real Bagehot’s prose almost to perfection and synthesising what the living Bagehot probably would have said.

Churchill’s First War by Con Coughlin (Raincoast Books, $31) refers to the incursion in Afghanistan during which the British failed to become the second western outsiders to conquer the place (Alexander the Great having at least partly secured some of it for a while). Some people believe that Sir Winston’s first published book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898), was also the finest of his published works, having been composed before victory and old age made his prose rotund. His history of the Second World War in six fat volumes, not to mention the various supplementary works related to it, isn’t much read any longer by the general public, though no one denies that such big wars should be examined at length. Three quite sizable volumes have been enough for the latest Second World War narrative history, the one by Rick Atkinson, late of the Washington Post.

Reviewers of Mr. Atkinson’s first and second instalments, An Army at Dawn and The Day of Battle, published in 2002 and 2007, respectively, often praised his graceful writing style. Now comes the concluding part, The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944–1945. Naturally enough, this one covers D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge and the Liberation of Paris. Writing about the last of these events, he mentions a bizarre little scene involving a pair of American soldiers (one imagines them as being like Willie and Joe, the characters in Bill Mauldin’s cartoons — three-day beards and all). The two GIs approached Ernest Hemingway, who was covering the Allied advance for a New York magazine and had personally liberated the bar of the Ritz. They asked him to ghost-write love letters to their girlfriends back home in the States. And Hemingway agreed. Mr. Atkinson doesn’t quote the letters, but one can easily imagine what they must have been like: “Madge, my love for you is like a river. Strong and fast and true. It is deep. It comes down from the mountains and runs through the countryside. It is fast.” Good grief.

An expanded 20th-anniversary edition of George Fetherling’s memoir Travels by Night has been published by Quattro Books.