The embers are hot yet again: In the aftermath of October’s attacks in Canada, some Americans are once again musing aloud about their northern border. Should Americans be concerned? What is the risk of lone wolves — such as Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, who killed Cpl. Nathan Cirillo at the National War Memorial, and Martin Couture-Rouleau, who drove a military vehicle off the road, killing Warrant Officer Patrice Vincent — and sleeper cells lying in wait in Canada, ready to pounce on the United States?

By my count, between 1997 and 2014, there were 16 cases involving 22 Canadians who ended up being convicted for terrorist activities that spanned the Canada-U.S. border. Just about all of the accused are male, and there is not a single lone wolf among them. (For detailed accounts of their deeds, see the sidebar on page 47.)

They fall into five categories:

1. Attempted attacks on the U.S. from Canada by Canadians: Al-Jawary, 1973; Mezer, 1997; Ressam, 1999; Dbouk and Amhaz, 2000.

2. Attacks on the U.S. by a Canadian recruited from the U.S.: Droege, 1981; Thurston and Rubin, 2005.

3. Drawing on support from the U.S. to increase capabilities of Canadians to engage in terrorism in Canada: Rose Brothers, 1970; Daher, 1993; Dirie, 2008.

4. Support for global terrorism from a joint Canada-U.S. base: Ayub, 1981; Al Safadi, 1996; Khalil, 2004; Daher, 2005; Thanigasalam, Sarchandran, Sabaratnam and Mylvaganam, 2006. 5. Support for global terrorism from a U.S. base by Canadians legally residing in the U.S.: Warsame, 2006; Rana, 2011.

There are only three cases of Canadians having been convicted of attempting to cross the border for the purpose of carrying out a Jihadi-inspired terrorist attack in the U.S., all of which predate 9/11: Mezer, Ressam, and Dbouk and Amhaz (Al-Jawary does not fit the Jihadi scope conditions). None of these cases could recur today with measures now in place, which suggests that the measures are

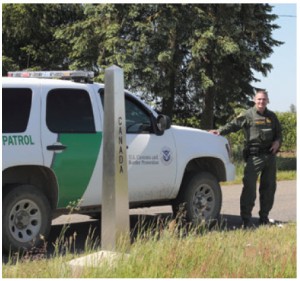

effective against deterring Jihadi-inspired incursions into the U.S. from Canada. That is because the aforementioned Jihadis crossed perfectly legally at ports of entry, some multiple times. The evidence thus suggests that devoting resources to counter-terrorism patrols between ports of entry along the Canada-U.S. border is futile.

Canada happens to border the world’s largest economy and the world’s largest weapons market. No surprise then that the bulk of cases involve individuals who cross into the U.S. to procure money and weapons. That is much the same reason Mexican cartels cross into the U.S. Some politically motivated violent extremists want to carry out attacks in Canada, but mostly they are bent on supporting violent extremist causes abroad.

It tends to be costlier and more difficult to obtain a firearm in Canada than in the United States, the source of the bulk of guns used to commit criminal offences in Canada, including those procured for the terror plots concocted by the “Toronto 18.”

There is thus no reason for Americans to worry about Canada being used as a staging ground for attacks on the U.S. Many Americans still believe the 9/11 attackers had links to Canada, however they did not. Americans should, however, be concerned about Canadians crossing the border to obtain money and weapons to fuel instability elsewhere in the world. Still, that dwarfs the direct supply from Canada and especially the U.S., to other parts of the world.

The U.S. poses a far greater security problem for Canada and the rest of the world, than Canada does to the U.S. Greater co-operation and more resources along the northern border aren’t likely to make either country any safer, but may just make the world a little safer from us. The northern border is not a threat to the U.S., but it is a problem for Canada and the rest of the world. For five years running, the RCMP has apprehended more people attempting to cross illegally from the U.S. into Canada than vice versa — despite Canada deploying disproportionately fewer resources along the border. In other words, people cross illegally between ports of entry, but terrorists are not among them. After all, who would incur the inconvenience and risk of crossing between ports of entry if they can cross legally at ports of entry?

Canada and the U.S. share the longest land border in the world. We also have the world’s closest bilateral security relationship. The U.S. has enough international security problems to worry about; Canada is not one of them.

Until October of this year, Canada had a first-rate batting average in thwarting attacks by homegrown terrorists on our soil: plots were few, people were charged, and, in many cases, convicted.

So, what went wrong this time? Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, who was responsible for the attacks in Ottawa that killed Cpl. Nathan Cirillo, and Martin Couture-Rouleau, who killed Warrant Officer Patrice Vincent with his car during an attack in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., had both shown up on security intelligence radar. Both had prior convictions, both had struggled with mental health issues, and both had known sympathies for politically motivated violent extremism. Triangulated with other indicators, that put them at an increased risk of moving from thought to action.

Evidently, Canadian security services do not have difficulty identifying at-risk persons per se. Why are they not being detained? The current legal framework puts several measures at their disposal, including national security certificates, preventative arrest and investigative hearings. However, absent robust evidence that an individual is looking to move from thought to action, Canadian courts are reluctant to approve of detention, let alone convict.

The federal government appears to be looking at more expansive powers of detention, perhaps by clarifying conditions and criteria for detention. These are currently ill-defined in the criminal code and normally require evidence for detention to be presented to a judge within 24 hours. The government may extend the permissible period for detention to buy police or security intelligence additional time to gather the necessary evidence in the case of national-security investigations. Similar measures already exist in other allied countries. In the U.K., for instance, the period can be up to 28 days.

The government also appears to be looking at criminalising association with or diffusion of discourse that incites politically motivated violent extremism against Canada or Canadians. Similar measures already exist in other areas of law, such as those criminalising the possession of child pornography or threatening someone else with violence.

Ultimately, though, these measures may not make much of a difference if the level of tolerance for the evidence required to detain and possibly convict is not actually lowered. That is more a matter of legal and societal culture than it is of law. In Canada individual freedom, civil liberties and privacy persistently seem to trump individual and public safety. Ergo, the government is proposing to lower some thresholds for warrants, for instance, from reasonable grounds to reasonable suspicion.

Allies such as the U.K., France, Germany and Spain have had to learn to live with terrorism, some for decades. As a result, their courts and their societies have developed greater sensitivity towards the protection of public safety. “He who sacrifices freedom for security deserves neither,” Benjamin Franklin famously said. But what about he who sacrifices security for freedom? Freedom and security are not a zero-sum dichotomy. To the contrary, they are complementary: You cannot enjoy one without the other. However, you also cannot enjoy your freedoms if you are dead.

Unlike Americans, Canadians are not inherently skeptical and mistrusting of their government. Why, then, reduce the Charter to a mechanism to “protect” Canadians from government? In criminal law, we tend to convict after an act has occurred. Anti-terrorism legislation, by contrast, is largely meant to deter individuals from moving from thought to action, and to prevent those who do contemplate action from actually realising their intentions. Canadian courts and Canadian society give the latter short shrift. The evidence that someone is looking to act needs to be overwhelming.

Tell that to the parents of Cpl. Nathan Cirillo; or to the parents of Michael Zehaf-Bibeau and Martin Couture-Rouleau. All would have preferred for the courts to err on the side of caution. So would most of the critics of the government’s proposed legislative changes: If it were they or their child who were harmed, they would be chastising the government for not having done more.

Decades ago, both individuals might have been committed to an asylum. Provincial governments have since gotten out of the business of institutionalisation, in part because it is expensive. Without the measures in place to protect such individuals from themselves on mental health grounds, it can fall to CSIS and the RCMP to take them out of circulation. CSIS, however, appears to have great trouble convincing the courts that some individuals should no longer be roaming freely; and the RCMP’s national security investigations are lengthy, in part because the evidence CSIS produces by-and-large does not withstand scrutiny in a criminal proceeding. With CSIS unable to detain and the RCMP evidently struggling to lay charges with the prospect of obtaining a conviction, are the courts imposing too exacting a standard of evidence?

The current equilibrium needs some rebalancing: If Canadian society and its courts can adapt, perhaps Canada may be able to do without expansive laws of detention, arrest and criminalisation. I value my freedoms; but I value my life and the lives of my compatriots even more.

More expansive powers for law enforcement and security intelligence need to be balanced with robust parliamentary accountability. My preferred model is Belgium’s where two permanent agencies headed by judges — the Comité R (renseignement) and the Comité P (police) — are empowered to audit not only past, but also ongoing investigations in real time and report their findings directly to a select group of security-cleared Members of Parliament.

But in the end, just as with child pornography or those who threaten to harm others, there comes an inflection point beyond which the protection of the collective interest enshrined in constitutional supremacy takes precedent over a denatured conception of individual rights. Michael Zehaf-Bibeau and Martin Couture-Rouleau were outliers; Parliament needs to assert its sovereignty to keep it that way.

Christian Leuprecht is associate dean and associate professor at the Royal Military College of Canada. He is cross-appointed to Queen’s University. His full study, Cross-Border Terror Networks: A Social Network Analysis of the Canada-U.S. Border, can be found in Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 5(2), pp. 155-175.