Pull on a wetsuit and snorkel gear and step into a fast-running river. Float effortlessly for kilometres in your buoyant lifejacket down the current, while 20,000 salmon are swimming under you in the opposite direction.

It is a thrill ride at five kilometres an hour down the swift-moving Campbell River on Vancouver Island’s east coast. You’re looking at the swirling mass of pink salmon beneath you while dodging boulders that come up fast.

How does one end up here? Chelsea’s Mike Beedell, adventurer-environmentalist-photographer and Diplomat Magazine contributor, was looking for a few people for his annual “Orcas & Otters Explorer” outing. The August trip includes beach explorations and sea-kayaking followed by a week on a yacht and in kayaks, looking at sea otters, humpback whales, orcas (killer whales), dolphins, sea lions and gorgeous jellyfish and sea vegetation.

The fascinating natural world aside, the trip has unknowns: What if the fish are so thick you can’t move? How cold is the water? What about living on a yacht for the first time, with a bunch of strangers, for a week? Or being seasick?

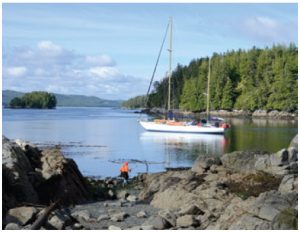

The yacht, the Ocean Light II, turns out to be a quick education in comfortable, but close sleeping quarters (two bunk beds per cabin) with a spacious dining room and deck. The 71-foot ocean ketch has 14 Atlantic crossings to her credit. The interior, rich in mahogany and Douglas fir, has a huge table for meals and computer work and easily seats the 10 guests.

Everyone gathers there for yacht-owner Jenn Broom’s home-cooked meals and diet-busting mid-afternoon baking. Since 1991, she has served as chief cook, first mate and guide.

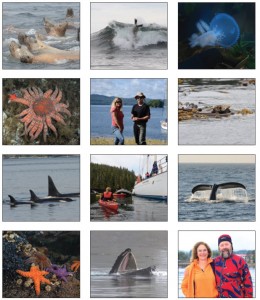

The enthusiastic sea lion welcoming committee swims up to visitors in Ocean Light II’s Zodiac; a surfing sea lion gets flipped out of the wave; hooded nudibranch; sunflower sea star; Jenn Broom, owner, and Chris Tulloch, skipper of Ocean Light II; sea otter wrapped in kelp (a good way to sleep); orcas fishing in formation; sea kayaking before breakfast; a humpback whale fluke during a hunting dive; sea stars; hunting humpback scooping up small fish before using the bristle-like baleen that line its mouth as a sieve; Donna Jacobs, Diplomat publisher and Mike Beedell, wildlife guide and contributing Diplomat photographer.

Close encounters

The yacht is skippered by Chris Tulloch, long a guide in B.C. waters and an expert in animal and plant identification. For years, he ran a research ship in Alaska that did humpback and orca identification. Ocean Light’s other skipper is Tom Ellison, a well-known environmentalist who once raised $2.5 million of $3 million needed to allow the Raincoast Conservation Foundation to buy up hunting tenures formerly used for grizzly bear trophy hunting. The funds came from a few of the yacht’s guests, who were inspired by their experience.

Both men have an uncanny ability to find, and often attract, dolphins, orcas and bears whose trust they’ve gained through many encounters. The creatures often get wonderfully close to the yacht or its sturdy silver Zodiac.

Also, the six kayaks aboard allow a slow mosey along the coastline rich in purple, dark red and bright orange sea stars (starfish). Some have only four legs, while others have as many as 20. Or you can try to follow a pulsating peach-coloured or tiny opalescent jellyfish.

The dining room turns into a post-dinner animated seminar where all the day’s species spottings, whether from water or walks, are listed on huge easel paper. And it’s where Skipper Tulloch pulls out maps to trace the day’s travels and tomorrow’s route.

We begin the 10-day excursion on Quadra Island, with Mike Beedell, at the simple and comfortable Taku Resort, 150 kilometres up the east coast of Vancouver Island and a ferry ride from Campbell River.

He familiarises us with “one of the most beautiful pursuits”: seakayaking (solo or double). “You’re self-propelled, your backside is below the ocean waterline so you’re feeling the pulse of the sea. You learn about currents, about waves. You don’t have to be very strong and can quickly get some sense of speed.”

We do feel the currents and learn to divide labours (front person steers with her feet) as we paddle with and against currents.

Fear of ferries

Never before did a B.C. ferry seem so threatening as when Mr. Beedell warned us to stop gazing around and race to safety because the Heriot Bay Ferry can’t stop or avoid us in the narrow channel. The huge ferry moves astonishingly quickly.

As we sit in our little red and yellow sea slippers on the open strait, the ferry looks like a white monster and we really do have to paddle fast to be well away from it and its turbulent wake.

It isn’t true danger, of course. Mr. Beedell knows all about the real thing. In 1976, he was at university and for a summer job, Trailhead in Ottawa hired him as a river guide on the Arctic Coppermine River north of Yellowknife. He bought a camera for the trip. While watching tens of thousands of caribou, white wolves hunting them, barren ground grizzlies and muskoxen, he met a gyrfalcon.

“I happened to be sitting on a cliff edge and the gyrfalcon landed with a ptarmigan (a rotund bird), in its talons, three to four metres away, dined and then cleaned the blood off his feathers. He got down from his noble falcon look and nestled down like a chicken and went to sleep.” Parks Canada bought his photos and gave him an assignment. He was hooked.

(Adventure runs in the family: His father, John Beedell, a former Olympic canoeist in the 1960 Rome Olympics, was an outdoor educator and biology teacher who taught at Ashbury College in Ottawa for decades and his mother, Ann, has been an active outdoorswoman.)

For death defiance, what could surpass Mr. Beedell’s and fellow Canadian, Jeff MacInnis’ record-making 4,000-kilometre trip — they were the first to sail through the Northwest Passage on wind-power in their catamaran. The 100-day journey (over the three summers of 1986-88) took them from Inuvik in the Northwest Territories to Pond Inlet on Baffin Island on a National Geographic Magazine assignment.

Just one entry in Beedell’s journal: “If we went over in these seas we could not get the boat back up. For a moment, I envisioned our flipping over, the sickening feeling of terror, the frigid ocean engulfing us. Then the quick, deadly numbing of our bodies and the absolute desperation before being swallowed up in the maw of an Arctic sea.”

Our own tame trip was incident-free, though being in a kayak and finding yourself quite close to a hunting humpback pumps plenty of adrenalin. Mr. Beedell quickly tells us how to hold onto our kayak in case the whale surfaces beside us. We are especially attentive after he tells us of a photograph he saw in which a humpback lifted a kayaker on its back and set it down neatly without ever tipping the little craft. “Humpies” are known as the most people-friendly whales.

The rest of the trip is aboard the Ocean Light II yacht, sailing the Johnston Strait for a week with Chris Tulloch and Jenn Broom, where every day produced surprises. They plan it that way. Ms Broom puts her work simply: “It’s joyful. There are so many experiences: sea otters mating, an orca in full breach, a blue whale, groups of up to 1,000 Pacific white-sided dolphins” along with bears, mink and seals that feed on migrating salmon and on halibut. She is concerned about disease and pollution from the salmon farms near B.C.’s salmon rivers that endanger wild salmon, and about Enbridge tankers and the B.C. government’s grizzly bear trophy hunt.

Life aboard a yacht is cosy in the cabins and convivial on deck and at the dining room table.

Surfin’ sea lions

Probably everyone’s biggest and most delightful surprise was that sea lions surf — really surf. They line up to play — to surf a wave that breaks over the only small reef in sight. They tread water until it’s their turn to be flipped out of the wave, though occasionally they triumph and ride the wave down and a cheer goes up from the Zodiac.

For a comedy show, nothing compares to the sea lions. Dozens of them are sleeping and sunbathing on large rock outcroppings near shore. The moment we approach, these non-surfers heave themselves into the ocean to swim out to the Zodiac as a hilarious, snorting welcoming committee.

They circle the craft and come right up to us as we lean over the side to see them. They come in droves with their huge brown eyes, long whiskers and greeting growls, all the while performing acrobatics around and under the inflatable.

For sheer exuberance, there is nothing like a leaping escort from Pacific white-sided dolphins, who race alongside in the V-shaped wave the yacht creates, turning on their backs and sides to have a good look at us.

And for awe, nothing can compare with being close to hunting humpback whales. The best sightings (aside from a friendly radio alert from fellow tour boats) begin with a gathering of shrieking sea birds.

They are drawn by fish, probably herrings, that gather in huge “bait balls” that churn the water into roiling silver flashes. Small diving birds, storm petrels, alert nearby humpback whales and before long, one or two arrive and perform one of the animal kingdom’s most astonishing hunting techniques.

Blowing bubble nets

This enormous whale — an adult measures 14-plus metres — turns in a tight circle, perhaps 50 metres down, producing bubbles of varying sizes from its blowhole. When the near-perfect circle is complete, the bubble net has entrapped thousands of fish. The humpback dives deep and comes crashing up right in the middle of the net, lower jaw (mandible) greatly dislocated forward, mouth agape to scoop up the fish. In shallow water, the whale feeds, its huge back forming a hump as it rises above the water between dives.

Dozens of orcas cruise the Robson Bight Ecological Reserve, where boat traffic is forbidden — one of the best places in the world to study orcas. Outside the reserve, for the first time in decades of guiding, Mr. Tulloch and Ms Broom see orcas using one of the well-known “rubbing beaches” where these members of the dolphin family flip onto their back and scratch and scrape clean and dislodge parasites on the smooth rocks. They also co-operate in driving prey fish to shore for easier hunting.

Sometimes we cruise by, listening to wolves howling or seeing black bears leisurely turning over shellfish on shore, in search of a meal.

There is more than the natural world to see. Alert Bay, with its huge historic and modern totem poles and 150-year-old heritage buildings, is the home of the Kwakwaka’wakw people, and where the U’mista Cultural Centre and museum is famed for its collection of ceremonial clothing and objects of art.

Nearby Telegraph Cove is ranked among the Top-10 best Canadian towns to visit by travel writers. The old boardwalk community offers accommodations and two marinas and its shops and restaurants support a brisk business serving tourists who use it as a launching place for wildlife viewing, sports fishing and boating. It has an extraordinary boardwalk, Whale Interpretive Centre with huge marine mammal skeletons, interactive and historical displays.

Researching orcas’ survival

In a sober evening at the centre, three scientists discussed the plight of orcas, especially the endangered southern population that swims between Vancouver, Victoria and Seattle and the threatened resident northern population in Canadian waters. They also express concern over the collapse of populations of western salmon, which is attributed variously to overfishing, diseases and sea lice infestations spread from unhealthy, unnaturally crowded farmed Atlantic salmon placed in Pacific salmon migration routes to natal rivers, from logging on salmon rivers and from sport fishing.

The scientists, Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard, Vancouver Aquarium’s senior marine mammal scientist, working with Drs. John Durban and Holly Fearnbach of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), among others, unveiled a new way to assess orcas’ health and keep track of individuals.

They use a $35,000 specially designed six-sided drone, a hexacopter, to photograph orcas without disturbing them. The precise laser measurements that the camera records from each individual photographed provides a good assessment of health and population numbers. The scientists made a disturbing, but useful discovery: Orcas can be starving, but still keep their rounded body shape. They take on water that masks thinness, but it cannot camouflage a “peanut head,” caused by the loss of fat between the blowhole and the back of their skull. That shape predicts imminent death for an orca.

Ocean Light II trips

Ocean Light II Adventures offers nearly three dozen B.C. coast trips, from May through mid-October (www. oceanlight2.bc.ca). They range from three days to a week. One trip, called Grizzlies of the Khutzeymateen, covers territory open to only two licensed outfitters and provides exploration of the grizzly sanctuary to 200 people a year. On the boat trips to the Khutzeymateen, Mr. Tulloch says the bears “end up ignoring us. They just act like bears and we’re quite close to them in the Zodiac. We see lots of fighting and mating. For me what is really remarkable is when they go to sleep right beside us or nurse their young beside us.”

The Ocean Light II makes frequent trips in the Great Bear Rainforest — famous for the white “Spirit Bear” variant of black bears, wolves and salmon. Another trip concentrates on orca-watching and exploration of Gwaii Haanas (Queen Charlotte Islands) aboard the yacht. And for kayakers, there is mothership-based sea-kayaking along the Gwaii Haanas to see salmon, sea lions, whales and porpoises and to explore tidal and coastline flora and fauna as well as outings to cultural attractions of the Haida people, who have inhabited the islands for 10,000 years.

Donna Jacobs is publisher of Diplomat magazine.