In June 2014, headlines marked the day: The global population of forced migrants had surpassed the 50 million mark for the first time since the Second World War.

In June 2014, headlines marked the day: The global population of forced migrants had surpassed the 50 million mark for the first time since the Second World War.

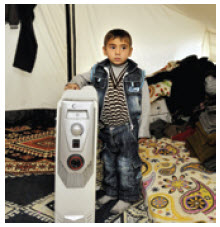

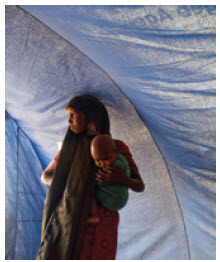

The war in Syria, along with conflicts in the Central African Republic, Ukraine and South Sudan were all major contributors to the meteoric rise of six million forcibly displaced people (which includes refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced persons) to the global refugee population since 2012. More than half of these individuals are children. International agencies such as the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), along with partnering NGOs, have been pushed to the breaking point of their ability to provide for even the most basic needs of these populations.

Nevertheless, there remains a great deal of misunderstanding of the crises that have led to the current global situation, as well as what is being done to mitigate the problem. Most observers in the West wrongly assume that Western countries are taking in the bulk of refugee claimants worldwide, while, in reality, more than 86 percent of refugees globally are hosted in the developing world. The burden of providing for the majority of the world’s refugees is unfairly placed on states neighbouring those in conflict, and the assistance provided by the international community is nearly negligible in terms of alleviating many of the worst cases.

The statistics are startling. The plight of forced migrants is not improving, despite increased international awareness. According to recent data, we now know that approximately every four seconds someone is forced to leave his or her home.

The average wait time for a refugee to be resettled is 20 years. In addition, nearly two thirds of the world’s refugees are in indeterminate exile. These statistics have only been getting worse; not only is the number of people stuck in prolonged refugee situations increasing, but the length of time they are there is becoming ever more unbearable.

Most protracted refugee situations stem from insecurity and violence. State fragility is of key concern here, with countries stuck in the “fragility” or “conflict” trap being the primary source of such refugees. It is estimated that this year, more than half of the world’s population living on less than US $1.25 per day will be living in fragile states. In addition, while global poverty is declining sharply, poverty levels have stagnated or even increased in fragile states. This means it is harder for these countries to escape the conflict trap, pushing ever more individuals and their families into unstable situations, within and beyond the borders of these countries.

With the above in mind, this article provides a snapshot of the Top 10 refugee-hosting countries, accounting for more than 56 percent of refugees hosted globally. Notably, the Middle East — in particular those countries close to the volatile situation in Syria — accounts for the most significant rise in asylum-seekers, refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). As can be seen in the country profiles below, the four-year civil war in Syria has resulted in an unimaginable flow of people out of the country (an estimated 2.5 million), placing strains on its neighbours through resource competition, economic uncertainty and lack of basic services.

To be sure, the situation in each country is unique, with different push-and-pull factors at work. At the same time, a number of common drivers of forced migration often interact, overlap and amplify one another. These include civil war and other forms of intra-state conflict, climate change, food insecurity, population growth, urbanisation, water scarcity, natural disasters and more. Each country’s situation is described in terms of the hosting nation’s characteristics as well as the sources of the refugee and asylum-seeker influx. It is also critical to remember that internally displaced persons make up an ever-increasing share of forced migrants globally, and often these populations are the hardest to reach to provide assistance, due to the political sensitivities associated with state sovereignty and intervention.

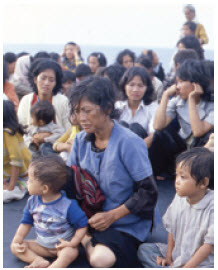

This article aims to shed light on the overarching causes of refugee flows and bring awareness to the extremely difficult situations faced by states in the global south. Policy responses that take into account all of these issues must be carefully crafted with local and regional contexts in mind. While the UNHCR, the IOM (International Organization for Migration), the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and other multinational organisations are working tirelessly to try to alleviate some of the most pressing crises, the fact remains that the developed world is largely ignorant of the scale of forced migration tragedies around the world. While the statistics presented above are staggering, it is critical for policymakers and lay-people alike to see the human face of the suffering occurring in unprecedented numbers. Only then will policies that direct much-needed resources to conflict-prone regions be able to make a lasting difference and provide durable solutions for those most affected by such tragedies.

1. Pakistan

Pakistan is home to the largest number of refugees in the world and has held this distinction for 22 of the last 35 years. Currently, approximately 1.6 million Afghan refugees are living in Pakistan. About 40 percent live in refugee villages and the remaining 60 percent in urban and rural host communities. Voluntary repatriation of Afghans who wish to return to their home country has improved the situation marginally. However, with the international security forces (the U.S.-led coalition) pulling out and the violence and political instability associated with hotly contested elections in 2014, the security of the country remains very fragile. Many Afghan refugees living in Pakistan are waiting to see what will happen within their home country before uprooting and returning, while a much larger proportion will most likely stay in Pakistan indefinitely. The large number of refugees has stretched resources and inflamed ethnic tensions, especially in the border regions of the country.

Why Pakistan has become host to the largest refugee population in the world is no mystery. Since the 1979 Soviet invasion, neighbouring Afghanistan has been subject to a great deal of political instability and conflict. The subsequent 2001 U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan resulted in a huge number of refugees fleeing nearly all regions of the country. Thus the “global war on terror” has resulted in the single largest refugee crisis of the past two decades.

2. Iran

The second-largest refugee population lives in Iran, which neighbours two war-torn countries — Afghanistan and Iraq. Even though hundreds of thousands of refugees have returned voluntarily to their home countries, the population in Iran is still massive. It has become home to approximately 900,000 refugees, with about 95 percent coming from Afghanistan and the remainder from Iraq. About 97 percent of refugees live in urban or semi-urban areas. The Iranian government has been generous in allowing refugees into the country and, for the most part, provides freedom of movement. Access to education, medical services, literacy classes and the labour market are all granted to refugees, a very important aspect of any reasonable response to a refugee crisis.

Unfortunately, inflation in Iran has led to increasingly difficult living situations that disproportionately affect refugees. Food prices along, with other essential goods, such as fuel, health and education costs, have all risen steadily over the past few years, with unemployment rising and wages remaining stagnant. Western sanctions on Iran — related to the country’s nuclear ambitions — are partly to blame for the slowdown in the Iranian economy. It is an unfortunate situation because the results of the sanctions affect the poorest and most marginalised populations much more than the government and business elites who control foreign and domestic policy decisions.

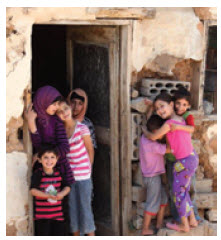

3. Lebanon

Lebanon has climbed up the list of refugee-receiving countries extremely quickly since the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011. More than 700,000 refugees from Syria were registered in Lebanon in 2013, indicating that the crisis is far from over. Estimates by the interior minister of Lebanon indicate that there may be upwards of 1.4 million Syrian refugees in the country. Add this to 200,000 temporary workers and you see that nearly a third of the country’s resident population is displaced.

The Lebanese economy has also taken a major hit due to the shock effects of the Syrian crisis next door, with rising debt levels having an adverse impact on the overall economic situation. As in Iran, inflation and costs of basic necessities are skyrocketing. Growth figures from the World Bank estimate a rate of 0.9 percent for 2013, far below the 9.2-percent rate from 2007-2012. Social tensions between native Lebanese and displaced Syrians are also becoming a major problem in border regions, with clashes occurring over dire employment prospects and jobs being taken by non-nationals, mainly in lower income-earning professions where competition has become fierce. Lebanon is not party to the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees, which means there is little legal protection for these vulnerable populations.

It is clear that the conflict in Syria has been nothing short of devastating for that country, as well as its neighbours. Since 2011, the death toll in Syria is estimated to be close to 200,000. Millions more have fled the country in search of safety. This conflict has created an incredibly unstable situation in which violence is not

confined within the borders of Syria, but has spread to such countries as Lebanon and Jordan. Further complicating this situation is the role of the militant wing of Hezbollah, which is based in Lebanon and has been observed providing troops and support to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government forces and exacerbating the war.

4. Jordan

The fourth-largest refugee population resides in Jordan, which registered nearly 700,000 Syrian refugees in 2013, only slightly behind Lebanon. Jordan is also home to at least 55,000 Iraqi refugees. There is a continual influx of Syrian asylum-seekers and despite generous resettlement policies, much of the existing infrastructure is being pushed to its limits. As in Lebanon, the global financial crisis has damaged Jordan’s economic stability, leaving key government services such as health care, education and basic infrastructure development to face significant difficulties in service delivery.

Jordan is also not a party to the 1951 refugee convention, so all UNHCR activities are codified in a memorandum of understanding signed in 1998. This agreement allows for refugees and asylum seekers to be afforded some, but not all, of the same protections offered under the 1951 convention, and therefore it is a critical tool in protection efforts. There are several camps set up for refugees, for example the Zaatari Camp, which houses 120,000

individuals. However, the majority of refugees are spread out across the country and live in urban or semi-urban areas, as they do in countries such as Iran and Lebanon.

Again, we see that the Syrian crisis has resulted in the increase in asylum-seekers and refugees in this fragile region. The sheer level of human suffering and uncertainty about the future cannot be overstated. This type of crisis illustrates how political factors can easily get in the way of managing conflict and its consequences. The stalemate at the UN Security Council has meant the war has continued unabated, without a solution in sight. All the while, international and domestic aid agencies and NGOs struggle to fulfil the most basic human needs of unprecedented numbers of people fleeing violence and persecution in their struggle to survive.

5. Turkey

The severity of the Syria crisis extends to Turkey, another country hard-hit by the civil war. The Turkish government estimates it has received more than 1.5 million refugees since the war started. An estimated 70 percent live in Turkish cities and the remainder are located in 21 camps across 10 provinces.

The Turkish government has enacted a law on foreigners and international protection that sets guidelines that fall in line with international standards for the protection of asylum-seekers and refugees. In addition, 2014 saw the establishment of a directorate general for migration management, a positive development for improving the standards of refugees and asylum-seekers in Turkey. UNHCR and Turkey work closely together to deliver essential services such as education and health care, along with legal and physical protection. As one of the more developed countries on our list, Turkey has had moderate success in managing the refugee crisis created by the war in Syria. However, if the flood of refugees continues at the current rate, it will quickly reach its limits.

Moreover, numbers of asylum-seekers in Turkey from countries besides Syria have also increased in recent years; top countries of origin include Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Somalia. UNHCR estimates 50,000 individuals have applied for asylum in the past two years, and the agency plays an active role in helping with status determination, registration and durable solutions, among other activities.

6. Kenya

Turning from the Middle East to East Africa, we see Kenya playing host to the sixth-largest refugee population on the planet. Kenya hosted close to 535,000 refugees in 2013, which represented a drop of about 30,000 people over the year. This decrease was mainly due to improvements and verifications in the record-keeping system that tracks registered individuals and voluntary repatriations. A new agreement between Kenya and Somalia, the Kenya Security Partnership Project, operating in the Dadaab area, aims to allow for movement of refugees back to Somalia.

On the other hand, asylum-seekers have been arriving in record numbers at Kakuma Camp. Basic services, infrastructure and protection needs are all areas of concern as more refugees arrive there. While the government of Kenya has been generally accommodating, after the 2013 terror attack by Al-Shabaab on the Westgate Shopping Mall in Nairobi, it has aimed to balance its security concerns with its humanitarian efforts, and, in doing so, has increased security in and around major refugee camps, especially those near Somalia.

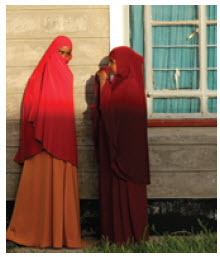

The primary populations of concern in Kenya are, from largest to smallest: Somalian, South Sudanese and Ethiopian. In South-Central Somalia, people are being driven from their homes in search of reliable food sources (escaping famine) as well as general safety, as the region remains extremely fragile and essentially lawless. Somalia has consistently been identified as the most fragile country in the world over the past two decades, and is often considered the archetype of a “failed state,” with no central government able to control the use of force within its borders or provide basic public services.

South Sudanese asylum-seekers and refugees have fled conflict and insecurity, with the 2010 referendum and subsequent split of Sudan producing ongoing violence, rather than the stabilising effect for which some analysts and policy-makers had hoped. Finally, Ethiopian migrants typically flee human rights abuses and low-level conflict in the border regions of that country.

7. Chad

Chad has had a steady increase in the number of refugees and asylum-seekers over the last 12 years. This is especially difficult due to the underdevelopment of the country. Chad ranked 184th on the Human Development Index and remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Political violence and corruption are major problems, and government capacity for even the most basic service delivery to its population is extremely poor. The majority of inhabitants live as subsistence herders and farmers, and government revenues come primarily from natural resources — crude oil in particular. These factors combine to severely limit the Chadian government’s ability to accommodate refugees.

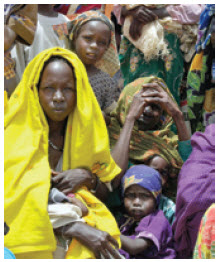

Ethnic violence and warfare in Central African Republic (CAR) in 2013 led to a major refugee emergency that spilled over into Chadian territory. More than 10,000 refugees and asylum-seekers arrived in the country. Luckily, Chad has an open-door policy towards refugees, as fleeing there was one of the only escapes for populations affected by the CAR violence. In addition, violence in Sudan, namely in West Darfur, drove a further 30,000 refugees into Chad in 2013. These influxes meant there were about 350,000 Sudanese and 740,000 CAR refugees residing in at least 17 different camps along the border regions. The government and UNHCR also opened a new camp to accommodate CAR refugees displaced by violence. Nigerian refugees also have a presence.

Politically, Chad is stable, however from the conflict research, we know that states neighbouring conflict zones are much more likely to erupt in violence themselves. UNHCR is working closely with the Chadian government to ensure protection exists for the most vulnerable refugee populations.

8. Ethiopia

Ethiopia, the second most populous country in Africa, is bordered by a number of fragile states. Its large area and unstable neighbouring nations mean there are numerous sources of asylum-seekers and refugees actively entering the country. In 2013, approximately 55,000 individuals arrived and this trend is expected to continue as several of the conflicts are ongoing.

The country is now home to the eighth-largest refugee population in the world at nearly 434,000 people. Most refugees are living in camps scattered throughout the country, again mainly found in the border areas, as would be expected. The government of Ethiopia has offered up significant pieces of land for the development of refugee camps and continues to make new land available for building new camps as more people arrive in need of protection. Police protection is also provided by the government, indicative of the needed balance between security concerns and humanitarian protection. Finally, there are some local integration campaigns through which the government and UNHCR will provide tuition funding for students to attend universities, a progressive policy choice not seen in many other countries.

Most refugees in Ethiopia arrive from Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan. Instability, oppression and famine are the three main drivers of asylum-seekers in this region, as was seen in the other African nations examined. The UNHCR works to promote activities that will allow them to make a living so communities can sustain themselves until durable solutions (mainly resettlement) are available.

9. China

China is a unique case for the ninth-largest refugee population in the world. The country is host to an estimated 301,000 refugees, the majority of whom arrived in the late 1970s and early 1980s after the fall of Saigon and increasing repression and discrimination towards ethnic Chinese (Hoa) people in Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge takeover in Cambodia near the same period also pushed a large number of refugees into China by land, air and sea. A number also fled Laos. This migration movement in Southeast Asia was termed the “Indochina Refugee Crisis” and, overall, an estimated three million people looked for refuge in China and other Southeast Asian countries. Many of the refugees were resettled in third countries such as the U.S. and Canada, while significant numbers stayed in China.

The current refugee situation in China is very stable, with most of the resettled being granted permanent status as residents. One development that has been catching international attention, however, has been the high number of North Koreans seeking asylum in China. China does not recognise North Koreans as legitimate refugees, arguing instead that they are fleeing poverty and, therefore, are considered economic migrants. Concurrently, the amount of international attention has prodded Chinese leaders to look towards the asylum policies of other countries and laws to regulate such activities are currently in the works. The politically sensitive nature of the matter means that it may take some time and clever manoeuvring to come up with a solution that is acceptable to all stakeholders.

10 U.S.

Notably, the only “Western” country to appear in the Top 10 — indicative of where the global refugee-hosting burden lies — the U.S. is currently host to approximately 264,000 refugees.

The U.S. is the highest donor to UNHCR and thus carries weight when it comes to policymaking within the organisation. While the resettlement program is well-funded and active around the world, the number of refugees who are eventually resettled to a developed third country is a drop in the bucket compared to the total numbers. The December 2013 UNHCR Global Trends report states that least developed countries (LDCs) host 2.8 million, or 24 percent, of the world’s refugees, and overall, the developing world hosts 10.1 million refugees, while the developed world only hosts 14 percent. And, according to the UNHCR’s latest figures, the proportion of those hosted by LDCs is growing. Given the much higher capacity and capability developed nations such as the United States have to integrate newly arrived immigrants and refugees, this proportion could easily be much higher without having any net negative effect.

That said, immigrants and refugees are arriving at the shores of developed nations illegally. In fact, one of the major challenges Western countries face is in weighing which people are legitimate refugee claimants who have stayed “in queue” and followed proper procedures and which are illegal migrants who bypass official pathways to enter countries and stay without proper documentation. Their presence makes it more difficult for those fleeing persecution to be heard.

Nevertheless, economics still tell the story: If one examines GDP (purchasing power parity), developed countries fall off the chart if GDP is taken into account: The 40 countries with the highest number of refugees per GDP in 2013 are in the developing world. A country such as Canada, that needs to sustain population growth in order to continue developing economically, could also shoulder a much greater proportion of the burden, with positive outcomes for the host nation and the refugees who have settled here.

Joe Landry is a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council’s Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada graduate scholar at Carleton University’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.