Imagine that your family has lived on the same land for generations. Over time, others arrive, take residence and establish a government whose rules now apply to you. But they do not include you in consultations — in fact, they specifically exclude you.

This was the situation facing Aboriginal Peoples in Canada for much of the period following Confederation in 1867. Although many First Nations people had the right to vote, it required renouncing their aboriginal status under a process known as “enfranchisement.” In 1885, under legislation brought forward by prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald, “Status Indians” — as they were known — who met existing requirements were given the right to vote. Yet Macdonald’s intent to extend the vote to all Aboriginal Peoples met with strong opposition. One result was that Aboriginal Peoples in areas involved in a recent Métis-First Nations rebellion were specifically excluded. In any event, that legislation did not last long: in 1898, seven years after Macdonald’s death in office, it was repealed.

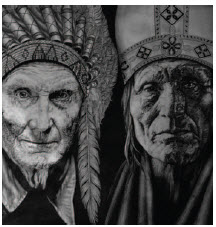

Why the reluctance to give Aboriginal Peoples the vote? Outright prejudice coupled with misguided, often paternalistic logic. The language used in the debate over the 1885 legislation was blunt and insulting — First Nations people were described as “low,” “filthy,” “barbarians” and “ignorant.”

Ultimately, it took participation in the First World War to give some Status Indians the vote, although it took until 1924 to fully enfranchise those veterans. In 1934, the Dominion Franchise Act explicitly disqualified First Nations people living on reserves as well as Inuit from voting, with the exception of war veterans.

In 1950, Inuit were given the right to vote; although many lived so far from voting stations that the change had little practical application. In 1958, prime minister John Diefenbaker, an advocate of Aboriginal Peoples’ right to vote, appointed the first First Nations member of the Senate, James Gladstone, or Akay-na-muka. In 1960, Diefenbaker’s government extended the vote unconditionally to Aboriginal Peoples; and eight years later, Len Marchand of B.C. became the first “Status Indian” elected as an MP. Still, because of bickering over the classification of women based on whether they married a “Status Indian” or “Non-Status” male, it was not until 1985 that the act was amended to remove prolonged elements of discrimination against First Nations women.

Today, while many challenges remain, new occasions exist for Aboriginal Peoples in Canada to reflect on their past, including frustrations and achievements. Historica Canada holds an annual Aboriginal Arts & Stories contest, inviting aboriginal youth to explore the stories of their peoples. Since 2005, more than 2,500 youth have submitted visual art and writing for consideration by our jury of aboriginal artists and writers. Among this year’s winners is Shaelyn Johnston, who placed first in the senior writing category for Anishinaabemowin, a story that addresses the issue of language loss and tells of one woman’s vow to pass on the Ojibwe language to her daughter.

Other occasions include the month of June — declared National Aboriginal History Month in 2009 — and June 21 declared National Aboriginal Day in 1996. In recent years, there is progress to celebrate: in the 2011 federal election, a record seven MPs of First Nations, Inuit or Métis origin were elected to the same House of Commons that once spurned their people.

Anthony Wilson-Smith is president of Historica Canada.