For as long as humans have existed, there have been tribes. Indeed, it is our ability to co-operate as members of discrete groups that has allowed for the resounding success of the species as a whole. Yet, in the modern, interconnected and globalized world, tribalism — which, at its base level, represents a separation of “us” versus “them”— has the ability to bind us closer together and drive us further apart, depending on how the phenomenon manifests itself.

The rise of the internet has, for example, allowed individuals from every corner of the globe to connect over shared interests, yet the expansion of Western culture has also resulted in a backlash in some traditional communities that feel their way of life and cultural values are being threatened. This paradox exemplifies the trouble with tribalism — it acts as a positive way in which humans build empathy with others and a flashpoint for conflicts new and old.

Determining what exactly constitutes a tribe is a difficult proposition. In the past, tribes were based on kinship and family traditions. Currently, ethnic groups and religious identities can be considered the strongest forms of tribalism. They are the ones that drive cohesion and conflict.

It is critical to recognize that there are no set rules on what exactly makes a society “tribal,” given the great diversity within and between tribes, yet they have common characteristics. Tribes are necessary to secure resources, such as access to land for farming or grazing activities. Competition over resources leads communities to work together, creating mutually beneficial arrangements and loyalty to one another. But tribes are complex social systems and they don’t remain static for long; allegiances can change quickly with shocks from within the community or those imposed from outside. At the same time, politics, religion, family life and community engagement are all closely intertwined. Reputation is extremely important, as is the concept of honour.

Tribalism alive and well

To be sure, in fragile and failed states, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (to name but a few prominent examples), tribalism in the more traditional sense is alive and well. This occurs when there is no central authority and the state lacks the capability and the will to enforce the rule of law within its borders, so individuals take charge of their own security by turning to those closest to them. Tribes are the only de facto social organizations in these societies and hence are very attractive to individuals.

Moreover, one of the biggest concerns stemming from the entrenchment of tribalism in the Middle East is the fact that members of Islamist extremist groups usually come from societies with strong tribal traditions. Recruitment of young men with little to no future prospects, who have also been raised in tribal societies, has proven to be easy. Many Taliban recruits in Pakistan, for example, are Afghan refugees with little education and no employment opportunities. Often they have been cut off from their tribe by forced displacement or various other reasons; joining an extremist group then represents a new start.

One prominent example of how tribalism can lead to international conflict and insecurity is currently playing out in Yemen. The Houthi tribe developed in the early 1990s as a small religious movement preaching peace in the north of the country. Over time, it has grown into a full-fledged insurgency, recently taking over the capital city, Sanaa, in the south and forcing the government from power. The movement capitalized on widespread discontent due to rising fuel prices and unemployment.

The stunning rise to power of this small, but organized tribal movement has in turn led to a proxy war between Shia and Sunni countries in the region — namely Iran, which supports the Houthis, and Saudi Arabia, which supports the ousted government. Saudi Arabia has been conducting airstrikes and providing funding to forces loyal to the Yemeni government. There is currently a call for a ceasefire and power-sharing talks, however the conflict shows little sign of abating any time soon. Now a massive humanitarian catastrophe has been created, illustrating how tribalism can have severe and far-reaching consequences.

Tribalism as political system

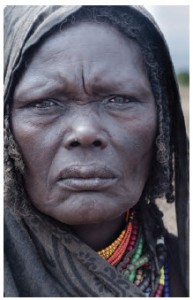

On the other hand, tribalism can also lead to co-operation, even when there has been conflict in the past. Generally speaking, there are three main ways that this can occur. In the first, tribal elites and politicians develop patronage networks. In these cases, common in sub-Saharan Africa, politicians typically originate from one of the main regional tribes. These leaders then build connections with other tribal leaders across the country, promising to provide access to key resources in exchange for political support. Leaders in countries such as Kenya, Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire have successfully managed to build stable regimes through such arrangements. They form the main economic and social mechanisms in many African countries, because the formal institutions are too weak to perform the same functions as would be expected in the industrialized world.

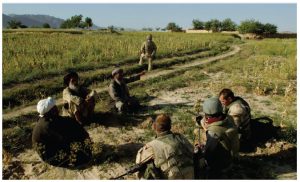

The second way in which tribalism can be harnessed is if there is unity against an outside enemy, often out of necessity. Such events have unfolded in Afghanistan multiple times over recent decades. Tribes in Afghanistan have overcome their ancient rivalries to fight against an external threat, whether it be the British, the Soviets, or, more recently, the American-led coalition forces. Having a foreign threat allows leaders of tribes to look past their previous conflicts and fight “for the greater good.”

This pattern is interesting because Afghanistan does not operate as a state in the traditional sense. Huge swaths of territory are left uncontrolled by any government forces. Cultural experts embedded with U.S. troops famously showed maps of the country to tribal leaders, with the leaders having no idea what the map was supposed to represent. To them, their tribal lands are all that matters and hastily drawn up borders have little to no bearing on their day-to-day life or personal identities.

The third way in which traditionally tribal societies can be wooed into working together is by emphasizing their commonalities in a positive way. Tanzania is one of the best examples of such co-operation. With the same population as Canada (35 million), residing in an area slightly smaller than the province of Ontario, Tanzania boasts staggering diversity. There are more than 125 ethno-linguistic groups throughout the country, yet conflicts between these groups are incredibly rare, and overall, they live in harmony. In addition, large populations of Christians and Muslims live side by side without problems. On the whole, people tend to identify as “Tanzanian” first and as part of their tribe second.

This shift was achieved after independence because the country’s first president, Julius Nyerere, emphasized and promoted use of the national language of Swahili and created a strong national identity based on the ideas of unity and freedom. Hence, while individuals still rely on their tribal linkages for their day-to-day life and politics, it is not seen as a flashpoint for conflict. Rather, they identify neighbours of different tribes as fellow countrymen. Overall, this has led to Tanzania representing an ideal state in sub-Saharan Africa when it comes to ethnic peace and societal cohesion. While the country has a long way to go in terms of economic development, many lessons can be learned from this unique form of co-operation.

A fine balance

Tribalism is alive and well even in today’s modern world. As societies continue to globalize and become more interconnected, balancing tribal instincts will become more difficult. The Aga Khan may have put this best: “[T]he great problem of humankind in a global age will be to balance and reconcile the two impulses of which I have spoken: the quest for distinctive identity and the search for global coherence … I believe that the co-existence of these two surging impulses … will be a central challenge for educational leaders in the years ahead.” This quote illustrates the fact that humans will have to find a way to identify with the groups closest to us while still building empathy for others who do not fit into those groups.

By improving our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the tribalistic impulse, we can better harness these drives for positive development. Simultaneously, it is vital to understand how tribalism operates to prevent its negative aspects, such as terrorism and civil conflict, from erupting and creating chaos.

Joe Landry is a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council’s (SSHRC) Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar and PhD candidate at Carleton University’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs. He is currently managing editor of the Canadian Foreign Policy Journal.