In September 2015, leaders from around the world gathered in New York City for the UN General Assembly and adopted the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Seventeen goals were agreed upon as part of the new framework, which lasts until 2030, including a goal on achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls. It’s a good thing, as much remains to be done on this pressing issue.

Although progress has been made toward gender equality over the past few decades, women and girls still face multiple barriers throughout their lifetimes. Deep-rooted social norms affect all aspects of society, resulting in visible and invisible forms of unequal power relations between men and women, as well as girls and boys. Gender roles based on stereotypical traits and ideas of what it means to be a man or a woman influence people’s attitudes and behaviour. This, in turn, leads to certain groups being valued less, and discriminated against, simply because of their sex, age, sexual orientation, race, disability, ability, location or religion.

Social norms and practices that favour patriarchy have resulted in generations of global gender inequality and discrimination against women and girls. This article will highlight just some of the challenges and barriers experienced by thousands of women and girls every day. Analyzing gender inequality from a life-cycle approach will highlight examples of unequal power relations and discrimination experienced by females at various stages of their lives. Clear examples from around the world offer insights into the approaches being used to tackle these important issues.

Women and girls are not homogenous groups of individuals. As such, examples of gender inequality vary throughout societies and countries, and are experienced differently by different groups. This does not change the fact, however, that millions of women and girls are being held back from achieving their full potential simply because of their sex or where they were born.

The world’s ‘missing’ girls

“I felt we could keep it only if it was a male and kill it if it was a female child. I just strangled it soon after it was born. I would kill it and bury it. Since we were not having any male children, I killed eight girl children.” — A woman living in India

In many countries, girls are discriminated against even before they are born. The prevailing tendency toward son preference has resulted in “gendercide,” in which the UN estimates that as many as 200 million girls are “missing” around the world.

Examining the sex ratio at birth (SRB) is one way of measuring the prevalence and breadth of son preference within countries. While the worldwide SRB average is biologically skewed in favour of males — approximately 105 males are born for every 100 females — it is largely due to males experiencing higher rates of mortality at all ages after birth in comparison to women.

Several countries have a skewed sex ratio at birth that far exceeds the worldwide average. According to the UNDP (United Nation’s Development Program), this trend is most evident in Asia, especially in China (where 116 males are born for every 100 females, nationally), India (111 males), Vietnam (110 males), and Eastern Europe, including Azerbaijan (115 males), Armenia (114 males) and Georgia (111 males). SRB ratios also vary significantly within countries, as there are likely higher rates of son preference in rural areas, and SRB becomes even more severe when the birth order increases and more children are born into the family. In countries that exhibit high levels of son preference, the SRB is often inconsistent with the worldwide average, and always unfavourable toward females.

Families who engage in female infanticide and preconceived sex-specific abortions in favour of boys do so often because of the patriarchal desire for male heirs, the devaluing of girls across all levels of society and the financial burden that girls will bring to their parents. As one young man in Serbia stated: “The firstborn must be male. After that it’s all the same.” Deep-rooted social norms perpetuate the notion that having a girl will result in a lower return on investment to the household and family, unlike boys, who can carry on the family name, provide physical labour to their rural households, contribute economically to the family’s well-being and support their parents in old age. Government policies also influence a country’s SRB by forcing families to limit the number of children they have, such as was previously the case with China’s one-child policy.

A distorted SRB caused by son preference has huge implications for society, including the perpetuation of gender inequality, the devaluation of girls and harmful intergenerational cycles of gender injustice. As one 15-year-old girl from South Africa asserts, “They all think that girls are supposed to be their doormat. I think boys must be taught to look at girls as people.” The practice [of killing girl fetuses and babies] is changing’ demographic compositions, leading to bride kidnapping and trafficking, forced and early child marriage and disgruntled bachelors. A skewed SRB impacts economic and social development and has long-term implications for countries.

South Korea’s new policy

Some countries have tried to regulate their SRB and eliminate the practice of son prevalence by rewriting policy, raising awareness and changing deep-rooted attitudes and harmful practices. A multi-sectoral approach is required to change harmful social norms that perpetuate son preference. For instance, the South Korean government implemented several strategies to tackle son preference and skewed SRB rates, including revoking its one-child policy and establishing a ministry of gender equality. It further launched an awareness-raising campaign called Love Your Daughter to promote gender equality and the value of girls within society. These efforts have helped to regulate South Korea’s SRB over the years, and the country now has a more balanced national rate of 107 boys for every 100 girls.

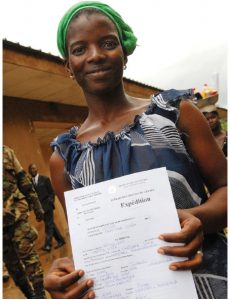

Registration: A birth right

“Who am I? Where did I come from? What’s my nationality? All I know is that my name is Murni, but I don’t have proof for that.” — A child in Indonesia

Birth registration is a universal right that all girls and boys have, as outlined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Having a birth certificate is required for almost every aspect of life, and opens endless doors of opportunity for children. A birth certificate is required for a child to register and attend school, it can help prevent early and forced child marriage by proving a girl’s age, it entitles a child to health benefits and it provides other social and economic opportunities. It is a powerful tool for achieving equity and gender equality.

Despite the importance of officially registering a newborn, UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) estimates that roughly 290 million children — 45 percent of all children under the age of five worldwide — do not have a birth certificate. While girls and boys are both at risk of not having proof of birth registration, boys overall are more likely than girls to have a birth certificate. Families with limited knowledge of, or access to, birth registration services, are less likely to register their children. Poverty and corruption can further impede a child from obtaining a birth certificate.

During a recent visit to Senegal, I had the good fortune of speaking with families living in the slums of Dakar. When asked why the dozen or so children living in the house were not in school, the community leader replied by saying that it was because only a few of the children had birth certificates, which are required for school enrolment. Those without certificates, nearly all of the girls in the house, were unable to go to school and were forced to stay at home and support the family with household duties. Despite birth registration being free and a universal right in Senegal and other countries, the family that I spoke with explained that corrupt officials seeking bribes, combined with household poverty, have prohibited them from formally registering their children.

Progress in Brazil

Brazil has taken great steps to increase national birth registration rates, from 64 percent in 2000 to 93 percent in 2011. In 1997, legal reforms guaranteed the right to free birth registration for all citizens. In 2002, birth registration was integrated into the health systems, and the ministry of health began providing a financial incentive to all maternity hospitals with an advanced birth registration post on their premises to allow for new parents to register their baby’s birth before returning home. In 2003, awareness-raising campaigns helped to promote birth registration, including the First National Birth Registration Mobilization Day, which led to a permanent national movement. In 2007, civil registration services in hospitals moved online, sending information instantly and directly to a national database system. The government is still working to achieve universal birth registration in Brazil, especially in the northern states, however the country has made great progress in one decade.

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation

“[My Grandma] caught hold of me and gripped my upper body… Two other women held my legs apart. The man, who was probably an itinerant traditional circumciser from the blacksmith clan, picked up a pair of scissors… Then the scissors went down between my legs and the man cut off my inner labia and clitoris. I heard it, like a butcher snipping the fat off a piece of meat. A piercing pain shot up between my legs, indescribable, and I howled. Then came the sewing: the long, blunt needle clumsily pushed into my bleeding outer labia, my loud and anguished protests…”

— Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a former refugee from Somalia, activist, politician and author of Infidel.

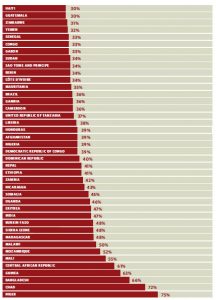

Torture. Child abuse. Gender-based violence. These are all words used to describe the practice of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). According to UNICEF, girls as young as five years old are victims of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the practice as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” In several countries, UNICEF calculates that more than 90 percent of women and girls have undergone FGM/C: 98 percent in Somalia, 96 percent in Guinea, 93 percent in Djibouti and 91 percent in Egypt. The procedure is often done in a girl’s home or somewhere in her community, rather than at a hospital or clinic with skilled health practitioners. For instance, UNICEF data reveal that in Yemen, 97 percent of girls who underwent FGM/C had the procedure done at home, and three-quarters of these girls were cut using a blade or razor.

Why are girls around the world experiencing unnecessary mutilation and cutting? Social conventions, traditional practices, family pressure — often from the mothers — and religious requirements are all explanations for why FGM/C continues to flourish in many countries, especially in Africa and the Middle East. Parents believe they are protecting their daughters and preparing them for marriage, as often times, girls are not seen as worthy of marriage if they have not been cut or sewn for their future husbands. According to Human Rights Watch, in Tanzania, a girl who has not undergone FGM/C “may be socially ostracized and referred to as ‘rubbish’ or ‘useless.‘”

Millions of girls and young women are at risk of being cut every year; many die from infection or bleeding, while others suffer permanent damage, such as infertility or difficulties with childbirth. The practice also takes place in Europe and North America among diaspora populations. In 2013, UNHCR calculated that more than 25,000 women and girls from FGM/C-practising countries sought asylum in Europe, mostly settling in Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, France, the U.K. and Belgium, among other countries.

Senegal’s story

In Senegal, civil society organizations have been working with communities to develop community-led social change initiatives to tackle harmful practices, including FGM/C. Through this process, communities develop their own solutions, based on new knowledge and skills acquired to collectively address a challenge in the community. Abandoning FGM/C was not the original intention of the organizations leading these initiatives. However, after learning about the harm brought by this practice, community members decided they were obliged to abandon them. As FGM/C is often performed in relation to preparing girls for marriage, if one community decides to abandon the practice, other groups with whom the community intermarries must also abandon it. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and UNICEF estimate that more than 4,500 communities in Senegal and neighbouring countries, including Burkina Faso, the Gambia, Guinea and Somalia, have abandoned the traditional practice of FGM/C.

Accessing education

“There are still biased attitudes towards girls’ education and some parents still believe that girls’ education has no value, and they cannot succeed even when educated.” A father in Ethiopia

Every child has the right to an education, yet according to Plan International, there are 75 million school-aged girls around the world not in school. One of the main explanations is that many families are stricken by poverty and cannot afford to pay school fees. While primary education is, or should be, free in the majority of countries, there are unforeseen costs that parents are unable to cover, including entrance fees, uniforms and exam fees. If there are financial limitations, families are more likely to pull their daughters out of school to perform household chores and caregiving responsibilities for young and old family members. If forced to choose, many families will choose their son’s education over their daughter’s. “Girls’ education was not a priority for most people. Most people married off their young girls to escape from high levels of poverty,” said Ayesha, a 14-year-old girl from South Sudan.

Some girls also suffer from sexual and physical abuse from students or teachers, forcing them to drop out for safety purposes, or in some cases because they have become pregnant and are banned from attending school. Child marriage also forces girls out of school, as once they become a wife, they are no longer seen as a child, and must perform the duties of a wife. A head teacher at a secondary school in Tanzania asserted that “when we find a pregnant pupil in school, we call a school board meeting where we agree to expel the pupil.”

Inadequate sanitation facilities and same-sex school latrines can also result in girls being victimized and harassed by boys, either physically or sexually. Such conditions can also force girls to drop out of school once they begin menstruating. Further explanations for the high number of out-of-school children include the proximity of their home to school. In remote areas, some students must walk for hours each way in order to access the school. Poor quality education puts further limitations on a child’s ability to learn, including the quality of teachers, teacher-student ratios, and gender discrimination in textbooks that perpetuate harmful gender norms and roles.

The 75 million school-aged girls out of school will be unable to acquire the skills and knowledge they need to protect themselves, they will have limited employment opportunities in the future, and they will be more vulnerable to child marriage, early pregnancy and other harmful practices. Education is often a tipping point in young people’s lives, helping to launch them into new, exciting and prosperous futures. As one young girl from Zambia states, “Without education I would be nowhere… education gave me confidence and made me a more responsible person.”

Nigeria’s positive steps

In Northern Nigeria, UNICEF’s Girls’

Education Project mobilizes religious leaders to advocate for girls’ education. Religious leaders inform community members that it is a religious duty to educate all children as outlined in the Koran and other religious texts, and they ask community members: “How can a society ensure there are sufficient female doctors and teachers to service the needs of its women if its daughters do not go to school?” Involving religious leaders has enhanced support from other community members in favour of girls’ education, and has been successful in changing harmful social norms that impede girls’ opportunities.

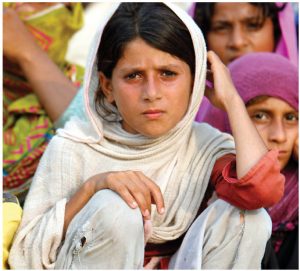

Forced child matrimony

Forced child matrimony

“When I was young, about seven or eight years old, my mother said I could not go to school because I had to go with her to the rice fields. One day I got a notebook and went to the school anyway. My mother came and dragged me from the classroom and took me back to the fields. Then one night when I was 14, a man came into my bed. I asked him who he was and he said he was going to be my husband. My mother had agreed I would marry him.” — 17-year-old girl from Laos

One in three girls in the developing world will be married by her 18th birthday, according to UNFPA; one in nine girls by her 15th birthday. Despite child marriage being illegal by international human rights law, and many national laws governing countries, child marriage continues to take place around the world on a vast scale. Weak legislation, such as the lowering of the legal age to marry below 18 years (international law’s standard), or making the legal age to marry lower for girls than boys, is one factor that can lead to child marriage. Astonishingly, UN data reveal that there are 43 countries and territories with a lower legal age of marriage for girls than boys, with the majority below the global norm of 18. Although as one child bride from Bangladesh points out: “What if there is [a] law? We do not see the laws working. [Until] now I have not seen the police arrest anyone because of child marriage. So, people are not scared of the law.”

Poverty is another factor that leads to child marriage: according to the UNFPA, girls from the poorest 20 percent of households are more than three times more likely to marry before they are 18 than girls from wealthy households. Parents are eager to marry off their daughters before the dowry price becomes too high, or as girls become older. Girls living in rural areas are twice as likely to be married by the age of 18 than girls living in urban centres. Lastly, UNFPA confirms that girls out of school or with no education are three times more likely to marry before 18 than those with a secondary education or higher.

While boys can also be victims of child marriage, the practice most often affects girls, and can have devastating consequences on their health and well-being. In addition to violating human rights law and global UN conventions, child marriage forces girls out of school and contributes to large dropout rates. As one child bride in Tanzania states: “I did not go to school as my father saw it as no use to take a girl to school, so after FGM, I was married off. My father had taken dowry, thus forcing me to get married at the age of 12 years.” A women’s focus group in Pakistan claimed: “In our community, we don’t allow a girl to continue her education when she is married because of her responsibilities. She doesn’t have any spare time to continue her education. Her in-laws and home should be her priority.”

Most significantly, child marriage leads to early pregnancy and health risks for girls. Every year, UNFPA data reveal that more than 13 million girls aged 15-19 in developing countries give birth while married. At the same time, complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of mortality for girls aged 15 to 19 in developing countries. Other health risk factors for young mothers include obstetric fistula, a damaging childbirth injury that leaves mothers unable to control their urine and/or fecal matter, causing pain, infections and social stigma that can ostracize women from communities.

Bangladesh’s child marriage-free zones

Child Marriage Free-Zones are being established across Bangladesh to tackle child marriage. Local governments, facilitated by Plan International Bangladesh and other NGOs, have made formal declarations for 22 out of the 35 zones throughout the country to be free of child marriage. This child-centred community development program is focusing on strengthening institutional mechanisms, investing in national- and local-level advocacy, building the capacity of girls and boys to say no to child marriage, raising awareness within the community and promoting partnership between community-based organizations and youth to work together.

School-related violence

“Our teachers should be there to teach us and not to touch us.” — 15-year-old girl from Uganda

Globally, between 500 million and 1.5 billion children experience violence every year, with many of these incidents taking place within schools. The WHO further estimates that 150 million girls and 73 million boys have experienced sexual violence worldwide.

These acts of violence can be described as “school-related gender-based violence” (SRGBV). Plan International defines SRGBV as “acts of sexual, physical or psychological violence inflicted on children in and around schools because of stereotypes and roles or norms attributed to or expected of them because of their sex or gendered identity. It also refers to the differences between girls’ and boys’ experience of and vulnerabilities to violence.” While girls and boys are victims of SRGBV, they experience different types of violence at different levels. For instance, boys are more likely to be victims of physical abuse or corporal punishment in school, while girls are more likely to be victims of sexual abuse.

Weak institutional frameworks, inadequate child protection mechanisms, as well as poor governance and monitoring are explanations for the prevalence of such violence. Unequal power relations and exploitation of children by teachers can also explain SRGBV. For instance, sex for grades is quite common, whereby male teachers exploit female students and coerce them into having sexual relations with them for grades or in order to waive school fees. As one 15-year-old girl raped by her teacher in Zambia explains: “I have been very much disturbed; emotionally disturbed and very much stressed. I am trying very hard to forget how it happened, but I am failing. I can’t just forget it; it’s like it’s just about to happen again, like it’s just happened. I remember every detail.”

Gender inequality, combined with other intersectional elements of discrimination, further perpetuates such violence. For instance, girls and boys of a certain sexual orientation, religion, race or disability might be at greater risk of SRGBV. With the increase in the use of technology, SRGBV is also occurring virtually, with more children and youth becoming victims of cyber-bullying. As a 17-year-old boy in Brazil claims: “You cannot go home from the internet … It is like being haunted.” Youth have also taken their own lives as a way of escaping cyber-bullying and the psychological violence that they endure.

Gender inequality, combined with other intersectional elements of discrimination, further perpetuates such violence. For instance, girls and boys of a certain sexual orientation, religion, race or disability might be at greater risk of SRGBV. With the increase in the use of technology, SRGBV is also occurring virtually, with more children and youth becoming victims of cyber-bullying. As a 17-year-old boy in Brazil claims: “You cannot go home from the internet … It is like being haunted.” Youth have also taken their own lives as a way of escaping cyber-bullying and the psychological violence that they endure.

The implications of SRGBV are vast, including increased dropout rates, lower academic achievement, reduced economic opportunities, increased health risks, suicide and intergenerational cycles of violence. Physical, psychological, and sexual violence are extremely harmful to the well-being of children, causing both short- and long-term implications. As one primary school student in Togo explains: “If the teacher hits me, everything immediately goes from my head. Even if I had lots of ideas before, the moment he hits me, I lose everything — I can’t think.” In addition, a 12-year-old girl from Spain asserts: “If they hit me, I learn to hit.”

Promoting safe schools in Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia

Tackling SRGBV requires multi-level approaches. One example is Plan International’s Promoting Equality and Safety in Schools (PEASS) program, which addresses SRGBV in Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia. The program, which works with governments, communities and individuals, aims to promote gender equality and non-violence in curricula and teaching practice; engage youth, communities and teachers in creating solutions together; advocate for policies that prevent SRGBV and protect girls in schools; and strengthen links between schools, homes and services. The program will increase the capacity of 2,500 teachers. It will work directly with nearly 150,000 adolescent girls and boys and advocate for five government ministries and 280 schools to recognize and endorse the Gender Responsive School model.

Another example is UNICEF’s Child-Friendly Schools (CFS) model that is being rolled out in multiple countries. UNICEF defines the CFS model as follows: “Schools should operate in the best interests of the child. Educational environments must be safe, healthy and protective, endowed with trained teachers, adequate resources and appropriate physical, emotional and social conditions for learning. Within them, children’s rights must be protected and their voices must be heard. Learning environments must be a haven for children to learn and grow, with innate respect for their identities and varied needs. The CFS model promotes inclusiveness, gender-sensitivity, tolerance, dignity and personal empowerment.”

Safe cities for females

Safe cities for females

“No one cares about us.” —Adolescent girl living in Cairo

In December 2012, a 23-year-old woman was gang-raped and murdered on a bus in Delhi, India. Incidents like this happen regularly in urban centres, yet there are few programs addressing the problem, and there is limited research on how to make cities safer, especially for adolescent girls. For instance, many urban safety and crime prevention initiatives target young men, and many women’s safety initiatives focus only on adult women — often in the domestic sphere.

For the first time in history, there are more people living in cities than in rural areas. UN-HABITAT estimates that each month, five million people are added to the cities of the developing world, and by 2030, approximately 1.5 billion girls will live in urban areas. Girls in cities contend with the duality of increased risks and increased opportunities. On the one hand, girls face sexual harassment, exploitation and insecurity as they navigate the urban environment, while, on the other hand, they are more likely to be educated and politically active and less likely to be married at an early age.

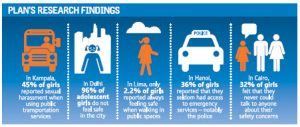

Research conducted by Plan International and partners revealed that adolescent girls seldom feel safe in cities. They experience physical and sexual violence and are often excluded from decision-making processes that impact their safety.

In Delhi, India, 96 percent of adolescent girls involved in the study said they do not feel safe in the city. These girls asserted: “The absence of lights in parks and other public places is a big problem. We feel unsafe while going to school as we have to leave early and [have] no company of other girls. At that hour, the roads are empty.”

Only two percent of adolescent girls in Lima, Peru, reported always feeling safe when walking in public spaces. “In public spaces and in the street, the city is very dangerous,” said an adolescent girl from Lima. “There are gangs, robberies, assaults; you can be kidnapped, followed, sexually harassed [and] raped. Walking in the streets is dangerous, especially in desolate areas; it is more dangerous at night when there is low light.”

In Kampala, Uganda, 45 percent of adolescent girls reported sexual harassment when using public transportation in the city. One young girl stated: “You tell a bodaboda driver to take you to Kawempe and he takes you somewhere else and he rapes you.”

More than one-third of adolescent girls in Hanoi, Vietnam, reported seldom having access to emergency services — notably the police. An adolescent girl from Hanoi said: “The roads are dark and large. If we call for help, no one can help us.”

In Cairo, Egypt, one-third of adolescent girls felt they could never talk to anyone about their safety concerns in the city. One girl said: “I want to give my opinion to make changes in the future.”

Explanations for these alarming figures include poor urban infrastructure, inadequate policies and limited city services. Gender inequality as well as harmful social norms and practices result in girls not being seen as valuable members of society or as equal citizens. Levels of physical and sexual violence against girls are seen as “normal,” meaning that girls rarely speak out about such injustices and when they do, their voices are ignored.

Adolescent girls’ safety program in Delhi, Cairo, Hanoi, Kampala and Lima

The innovative and ground-breaking Because I am a Girl Urban Program was developed by Plan International, Women in Cities International and UN-HABITAT. It aims to build safe, accountable and inclusive cities with, and for, adolescent girls (ages 13-18). The program is being carried out in five cities around the world: Delhi, Cairo, Hanoi, Kampala and Lima. The three outcomes of the program for girls include an increase in their safety and access to public spaces, an increase in their active and meaningful participation in urban development and governance and an increase in their autonomous mobility in the city.

The program works across three levels of change to create sustainable solutions for girls, including working with governments and institutions to make laws and policies gender-sensitive, child-friendly and inclusive; working with families and communities to create a supportive social environment that promotes children’s rights and the participation of all girls and boys; and working with girls and boys to be active citizens and agents of change by building capacities, strengthening assets and creating opportunities for meaningful participation. The program is working directly with 15,000 adolescent girls, 9,000 government stakeholders and transportation staff and 750,000 community members to make cities safer and more inclusive for girls and communities as a whole.

Intimate partner violence

“The reality is many of us have been sexually and/or physically abused as children or as adults, as were our mothers and grandmothers — in some ways the abuse has become normalized, pervasive and constant.” — First Nations woman living in Winnipeg

Globally, according to the WHO, one in three women will experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner, or sexual violence from a non-partner in their lifetime. While men are also victims of intimate partner violence, the level of violence against women is far higher and often more severe.

Women often have less decision-making power within and outside the household due to unequal power relations between women and men, girls and boys. Women have limited ability to control household resources or decisions, and the men are often perceived to have the upper hand, largely as a result of earning more income for the household. Substance abuse and violent tendencies can also explain such high levels of domestic violence. A shift in power between household members can also lead to disruptions and an increase in violence. In addition, limited knowledge about what constitutes violence can lead to further violence. As one woman in Burkina Faso claims: “We don’t know our rights. We don’t know laws very well. Not beating your wife — is that in the laws?”

Victims of domestic violence suffer from physical and psychological trauma. Some cases even result in death. Based on research by the WHO, more than one third of all murders of women are committed by intimate partners. Victims are also more vulnerable to health issues. For instance, the WHO states that women who have been physically or sexually abused by their partners are 16 percent more likely to have a baby below healthy weight, more than twice as likely to have an abortion, twice as likely to experience depression and, in some areas, 1.5 times more likely to acquire HIV.

According to Statistics Canada, every five days, on average, a female is killed by her intimate partner in Canada. Certain groups of women are more vulnerable. For instance, young women are two to three times more likely than older women to report having experienced intimate-partner violence over the past year, and they are 10 times more likely than young men to experience dating violence. Women with disabilities are more likely to have experienced spousal violence. In addition, aboriginal women are three times more likely than non-aboriginal women to report being a victim of a violent crime in Canada, and they are four times more likely to be murdered.

India’s Bell Bajao! Campaign

The Ring the Bell campaign, launched in India in 2008 (known locally as Bell Bajao!), encourages men and boys to take a stand against domestic violence. The campaign developed a series of award-winning public service announcement videos showing men and boys taking a stand and ringing a neighbour’s doorbell to interrupt domestic violence. Inspired by true stories, these short videos went viral and have been viewed by more than 130 million people. The Ring the Bell campaign is now a global initiative calling on one million men to take concrete action to end violence against women.

Economic empowerment

Economic empowerment

“[Women] are discriminated against in salary even though they both do the same work; for example, at the local plastics factory, a woman gets 900 NIS ($247) a month and a man gets 1,800 NIS ($495).” — A young woman living in the West Bank and Gaza

There are several barriers that women face in achieving economic empowerment, including limitations in accessing safe employment opportunities, as well as barriers once they join the workforce.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), nearly half of the world’s employed populations are working in conditions with limited access to decent work, with women constituting the majority of this workforce. This is most prevalent in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where women are more likely than men to work in the informal sector, and nearly half of the world’s working women are employed in low-paid and undervalued jobs.

Women are often employed in the informal sector due to limitations in accessing formal employment. Housekeeping and caregiving duties often limit a woman’s time to seek outside work. World Bank research reveals that women devote one to three hours more than men to housework, two to 10 times the amount of time a day to caregiving and one to four hours less to involvement in market activities. Unpaid household and caregiving work is undervalued and often not measured in monetary terms.

In 1995, the UNDP calculated the monetary value of the unpaid working industry, together with the underpayment of women’s work, which equated to US $16 trillion. US $11 trillion of this was the “non-monetized, invisible contribution of women.” According to a more recent study by UN Women, if women’s wages were raised to the same level as men’s, the GDP would be nine percent higher in the U.S., and 13 percent higher in the EU.

In 1995, the UNDP calculated the monetary value of the unpaid working industry, together with the underpayment of women’s work, which equated to US $16 trillion. US $11 trillion of this was the “non-monetized, invisible contribution of women.” According to a more recent study by UN Women, if women’s wages were raised to the same level as men’s, the GDP would be nine percent higher in the U.S., and 13 percent higher in the EU.

Further challenges occur once women are employed in either the formal or informal sectors. The gender wage gap exists globally. Based on research conducted by the ILO in 83 developing and developed countries, it was found that women are paid 10-30 percent less than their male colleagues. Statistics Canada data from 2011 outline that the gender wage gap in Ontario is 26 percent, meaning that for every dollar a male employee earns, a female employee earns 74 cents. In addition, women are also less likely to hold leadership and senior management positions in organizations or act as board members.

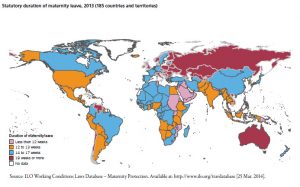

A further impediment to women’s economic empowerment is inadequate parental leave, as well as affordable and accessible daycare. The ILO estimates the majority of female workers around the world — approximately 830 million women — don’t have adequate maternity protection. More than three-quarters of those workers are in Africa and Asia.

In some countries, national legislation provides excellent parental leave, including in Scandinavian countries such as Finland, Norway and Denmark. In other countries, including the U.S. and throughout the Middle East, paid parental leave is either not mandated by the government, or, if it exists at all, is extremely limited. Without equal and inclusive parental leave policies that promote equal opportunities for mothers and fathers, including for parents who adopt children and same-sex couples, women’s opportunities will be stifled and the gender gap in the labour force will persist.

A further barrier to women’s economic empowerment can be found in inadequate and discriminatory land rights, inheritance, marriage and divorce laws. According to the World Bank, in 16 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, more than half of female widows do not inherit any assets from their spouses; in 14 of these countries, assets were inherited by the husband’s children and family members. As one young woman in Afghanistan claims: “When you die, your property is distributed by your relatives, and does not go to your wife or daughter. If you have a son, all property will belong to the son.”

Iceland’s parental leave

In 2000, Iceland dramatically changed its parental leave scheme, extending the total leave period to nine months. Three months are allocated to the mother and three months to the father. This is non-transferable. The remaining three months can be divided between the parents as needed, and full-time working parents receive 80 percent of their former salary during parental leave. The policy has been extremely successful, with 90 percent of fathers using their parental leave and taking, on average, 101 days, with women using 181 days on average.

India’s trade union for self-employed females

In terms of enhancing women’s economic empowerment in the informal sector, the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in India provides a good example. Established in 1972, SEWA is the country’s largest trade union, consisting of poor and self-employed female workers in the informal sector throughout the country. In 2013, SEWA’s membership exceeded 1.9 million women. SEWA improves women’s working conditions, incomes and social security through initiatives on micro-finance via the SEWA Bank, capacity building and training and its policy work on labour issues, including lobbying for health insurance, maternity benefits and pensions. SEWA members have reported an increase in earnings and savings, improved working conditions, as well as enhanced self-esteem, empowerment and improved bargaining power within and outside of their households.

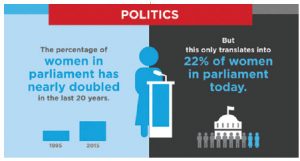

Political participation

Political participation

“I believe that women’s participation is fundamental to democracy and essential to the achievement of sustainable development and peace… Countries with more women in parliament tend to have more equitable laws and social programs and budgets that benefit women and children and families.” — Michelle Bachelet, Chilean politician and former executive director of UN Women

Political participation and the representation of women in government are important in ensuring that women’s and girls’ rights and interests are being properly addressed. Yet, women around the world have limited access to political participation. Globally, only 22 percent of all national parliamentarians are female, and UN Women data reveal that only 11 heads of state and 13 heads of government are female. The minimum international benchmark for women’s political participation is at least 30-percent representation, although dozens of countries fall short of this goal.

Stereotypical gender roles tend to pigeonhole women as being responsible for managing the household, with men seen as being responsible for aspects outside of its walls. This arrangement is different across various countries, though for the most part, women’s household duties limit their opportunities for getting involved in politics. Women either feel unqualified or fundamentally outside of their realm.

Opportunities must be created to promote women’s involvement and participation in decision-making processes across all levels of government. The number of female candidates must be increased to ensure a balanced representation, and women should be present in all political fields, not just those aligned with women’s interests or stereotypically female-related. Support must also be provided to women in terms of training and mentorship to ensure that the quality of their candidacy is top-notch. This is not to say that men cannot be champions of gender equality and equal laws for all citizens. Many are. Yet, with women’s political representation dramatically lagging behind that of men, governments must promote equal opportunity for men and women to be involved in politics and to be active and valued citizens in their countries.

Rwanda stands out

Rwanda is an exception, and has the highest number of female parliamentarians in the world: Nearly 64 percent of seats in the lower house and 38 percent of seats in the upper house are occupied by women. This can largely be attributed to strong institutional mechanisms, a strong women’s rights movement, changes in gender roles after the 1994 genocide and the commitment of the Rwandan ruling party to gender parity and women’s issues.

In terms of strong institutional frameworks, the new constitution, which was developed and adopted in the early 2000s, toward the end of the post-genocide transitional period, incorporates a quota system granting women a minimum of 30 percent of positions in all decision-making entities. In addition, grassroots administrative units, known as women’s councils, were developed for women only and represent women’s concerns.

Rwanda also has a strong women’s rights movement that has paved the way for a shift in gender roles and norms throughout society. The Rwandan genocide, which led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, also changed the demographic makeup of the country, resulting in women and girls making up 70 percent of the population immediately after the genocide. Women were forced to take on roles of household heads, wage earners and community leaders and started assuming non-traditional roles in society and acquiring new skills.

Toward gender equality

Though widespread discrimination against girls and women continues to exist at unacceptable rates, this need not be a reality. It is possible to stop this vicious cycle of inequality and work together to tackle its root causes, thereby changing harmful social norms and practices and shifting unequal power relations between women and men, girls and boys. We need to shatter the glass ceiling that limits women and girls from thriving in their societies, and must equal the playing field to ensure that all girls and boys, women and men, have the same opportunities to flourish. We need to start listening to what this 19-year-old girl from India is truthfully telling us: “When you go to school and do well, the world forgets what you cannot do and starts seeing what you can [do].”

Alana Livesey is a gender equality specialist and is currently the program manager for Plan International’s Because I am a Girl Urban Program.

- SDGs (2015). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics

- It’s a Girl Documentary Film – Official Trailer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISme5-9orR0

- The Economist (2010). Gendercide: The War On Baby Girls. http://www.economist.com/node/15606229

- UN (2007). International Women’s Day. Take Action to End Impunity for Violence Against Women and Girls. http://www.un.org/events/women/iwd/2007/factsfigures.shtml

- Sen first coined the phrase ‘missing women an girls’. Source: A. Sen, (1990). “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing”, The New York Review of Books, Vol. 37, No. 20.

- UNDP (2010). Human Development Report 2010, The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development (New York: United Nations).

- Coale, A.J. (1991). “Excess Female Mortality and the Balance of the Sexes in the Population: An Estimate of the Number of ‘Missing Females’”, Population and Development Review, Vol. 17, No. 3.

- UNDP (2014). Human Development Report 2014. Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience. (New York: UNDP).

- X. Wen, (1993) “Effect of Son Preference and Population Policy on Sex Ratios at Birth in Two Provinces of China”, Journal of Biosocial Science, Vol. 25.

- World Bank (2012). World Development Report 2012. Gender Equality and Development (Washington: World Bank).

- Human Rights Watch (2001). Scared at School: Sexual Violence against Girls in South-African Schools. (New York: Human Rights Watch). http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/03/01/scared-school

- For more, see: Hudson, Valerie M. and Andrea M. Den Boer (2004).

- Song, J. (2009) “Rising Sex Ratio at Birth in China: Responses and Effects of Social Policies”, Paper for the 26th International Population Conference at Marrakech, Morocco, 2 October; WHO, UN Women, UNICEF, UNFPA, and OHCHR (2011). Preventing Gender-Biased Sex Selection: An Interagency Statement (Geneva: WHO Press).

- Plan International (2009). Count Every Child. The Right to Birth Registration (Woking: Plan International).

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), Article 7.

- UNICEF (2014). Birth Registration. http://www.unicef.org/protection/57929_58010.html

- UNICEF (2013). Every Child’s Birth Right. Inequities and trends in birth registration (New York: UNICEF).

- Ali, Ayaan Hirsi (2007). Infidel (New York: Free Press).

- UNICEF (2013). Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Statistical Overview and Exploration of the Dynamics of Change (New York: UNICEF).

- WHO (2008), Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation: An Interagency Statement (Geneva: WHO).

- Human Rights Watch (2014) Child Marriage: Tanzania (New York: HRW).

- UNHCR (2014). Too Much Pain. Female Genital Mutilation and Asylum in the European Union. A Statistical Update. March 2014. http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5316e6db4.pdf

- UNFPA and UNICEF (2009). The End is in Sight. Moving Toward the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (New York: UNFPA and UNICEF).

- Plan International (2012). Because I am a Girl, Africa Report, Progress and Obstacles to Girls’ Education in Africa (Woking: Plan International).

- Plan International (2012). Because I am a girl. The State of the World’s Girls 2012. Learning for Life (Woking: Plan International).

- Human Rights Watch (2014) Child Marriage: Tanzania (New York: HRW).

- Plan International (2012). Because I am a girl. The State of the World’s Girls 2012. Learning for Life (Woking: Plan International).

- Akunga, Alice and Ian Attfield (2010),“Northern Nigeria: Approaches to Enrolling Girls in School and Providing a Meaningful Education to Empower Change”. Presented at UNGEI’s Engendering Empowerment: Education and Equality. Dhaka, Senegal, 17-20 May 2010.

- UNFPA (2012). Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage (New York: UNFPA).

- Child marriage is prohibited as outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (1978), the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989), and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990).

- UN Data (2013). Legal Age for Marriage http://data.un.org/DocumentData.aspx?id=336

- Plan International Asia (2013). Child Marriage Initiative: Summary of Research in Bangladesh, India and Nepal Bangkok: Plan Asia Regional Office).

- According to UNFPA data, more than half (54%) of girls

in the poorest 20 percent of households are child brides, compared to only 16% of girls in the richest 20%of households. Source: UNFPA (2012). Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage (New York: UNFPA). - FORWARD (2011). Voices of Tarime Girls: Views on Child Marriage, Health and Rights (London: FORWARD).

- Plan Finland and Åbo Akademi University (2011). Stealing Innocence: Child Marriage and Gender Inequality in Pakistan (Helsinki: Plan Finland).

- Based on UNFPA data that each year, nearly 16 million adolescent girls aged 15-19 years old give birth; about 95% of these births occur in low- and middle-income countries. Ninety percent of these adolescent mothers in developing countries are married. Source: UNFPA (2012).

- Human Rights Watch (2013). Child Marriage: South Sudan. (New York: HRW).

- Plan International Bangladesh (2013). Report on Child Marriage Free Unions http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/reports-and-publications/child-marriage-free-zones/ . See also the Wedding Busters: Stopping Child Marriage in Bangladesh video http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/meet-the-wedding-busters-stopping-child-marriage-in-bangladesh/

- Plan International (2010). Because I am a Girl. The State of the World’s Girls 2010: Digital and Urban Frontiers: Girls in Changing Landscapes (Woking: Plan International).

- UNICEF (2009). Child Protection from Violence, Exploitation, and Abuse. http://www.unicef.org/media/media_45451.html

- Plan estimates that at least 246 million boys and girls suffer from school-related violence every year. Plan’s estimate is based on the following calculation: the 2006 UN Study on Violence against Children reported that 20-65% of schoolchildren are affected by verbal bullying—the most prevalent form of violence in schools. Based on UNESCO’s 2011 Global Education Digest report, 1.23 billion children are in primary or secondary school on any given day, and Plan estimates that 20% of the global student population is 246 million children. Therefore, Plan estimates that at least 246 million boys and girls suffer from SRGBV every year. Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2011). Global Education Digest 2011: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World (Montreal: UNESCO Institute of Statistics).

- World Health Organization (2002). World Report on Violence and Health (Geneva: WHO); United Nations Secretary General(2006). Report of the Independent Expert for the United Nations Study on Violence Against Children (New York: United Nations).

- Plan International (2013). A Girl’s Right to Learn Without Fear. Working to End Gender-Based Violence in Schools (Woking: Plan International).

- Plan International (2008). Learn Without Fear: The Global Campaign to End Violence in Schools (Woking: Plan International).

- Plan International (2012). Learn Without Fear: The Global Campaign to Stop Violence in Schools, Third Progress Report (Woking: Plan International).

- Plan International, UNICEF, Save the Children Sweden, and ActionAid (2010). Too Often in Silence: A Report on School-Based Violence in West and Central Africa (Dakar: UNICEF, Plan West Africa Regional Office, Save the Children; Johannesburg: ActionAid). http://www.unicef.org/wcaro/VAC_Report_english.pdf

- Plan International (2013). A Girl’s Right to Learn Without Fear. Working to End Gender-Based Violence in Schools (Woking: Plan International).

- Plan International Asia and ICWR (2015). Are Schools Safe and Equal Places for Girls and Boys in Asia? Research Findings on School-Related Gender-Based Violence. Summary Report (Bangkok: Plan International Asia Regional Office).

- UNICEF (2010). Child-Friendly Schools. http://www.unicef.org/education/index_focus_schools.html

- Plan International, Women in Cities International, and UN-HABITAT (2013). Adolescent Girls’ Views on Safety in Cities. Findings from the Because I am a Girl Urban Programme Study in Cairo, Delhi, Hanoi, Kampala, and Lima (Woking: Plan International; Montréal, Women in Cities International; New York, UN-HABITAT). https://plan-international.org/adolescent-girls’-views-safety-cities

- UN-HABITAT (2008), State of the World Cities Report 2008-2009. (Nairobi: UN-HABITAT).

- Plan International, Women in Cities International, and UN-HABITAT (2013). Adolescent Girls’ Views on Safety in Cities. Findings from the Because I am a Girl Urban Programme Study in Cairo, Delhi, Hanoi, Kampala, and Lima (Woking: Plan International; Montréal, Women in Cities International; New York, UN-HABITAT). https://plan-international.org/adolescent-girls’-views-safety-cities; Plan International, Women in Cities International, and UN-HABITAT (2014-5). Because I am a Girl Urban Programme: Global Baseline Analysis Report. Baseline Findings from Delhi, Hanoi, Kampala, and Cairo (Woking: Plan International; Montréal, Women in Cities International; New York, UN-HABITAT).

- Macleans (2015) ‘It Could Have Been Me’. Thirteen Remarkable Women Share Their Own Stories http://site.macleans.ca/longform/almost-missing/

- WHO, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and South African Medical Research Council (2013). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence (Geneva: WHO).

- In 2011, there were 89 intimidate partner homicides in Canada, 76 were female victims. Source: Samuel Perreault (2011). Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2012001/article/11738-eng.pdf

- Statistics Canada (2008). Police-Reported Dating Violence in Canada.

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2010002/article/11242-eng.htm

- Statistics Canada (2009). Violent Victimization of Aboriginal Women in the Canadian Provinces. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2011001/article/11439-eng.htm

- Bell Bajao! (2012). http://www.bellbajao.org/home/about/. Here are the links to some of the Ring the Bell videos:

- India: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1h_UaPJlhY; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qAYDmZ19nG4; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9t3BPv8tBP4

- China: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abkj99Zx8Kg; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVN0-RSj-fE

- ILO (2015). World Employment Social Outlook. Trends 2015. (Geneva: ILO).

- ILO (2012), Global Employment Trends for Women (Geneva: ILO) http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_195447.pdf

- UNDP (1995). Human Development Report 1995. (Oxford: UNDP and Oxford University Press).

- UN Women (2013) In Brief: Economic Empowerment of Women. http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2013/12/un%20women_ee-thematic-brief_us-web%20pdf.ashx

- UN Women and ILO (2012). Policy Brief. Decent Work and Women’s Economic Empowerment: Good Policy and Practice. (New York: UN Women).

- Ontario Government. Pay Equity Commission. (2014). Gender Wage Gap http://www.payequity.gov.on.ca/en/about/pubs/genderwage/wagegap.php

- ILO (2014) Maternity and Paternity at Work. Law and Practice Across the World (Geneva: ILO).

- Centre for Gender Equality in Iceland (2012). Information on Gender Equality Issues in Iceland. https://www.althingi.is/pdf/wip/Gender_Equality_in_Iceland_2012.pdf

- SEWA (2009). About Us http://www.sewa.org/About_Us.asp

- SEWA (2013). SEWA 2013: Annual Report http://www.sewa.org/pdf/Sewa_Annual_Report.pdf

- UN Women (2011) Women’s Political Participation http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2011/10/women-s-political-participation

- Women in National Parliaments (2015). http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm

- UN Women (2015) Facts and Figures. Leadership and Political Participation. http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures

- Women in National Parliaments (2015) http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm

- Powley, Elizabeth (2005). “Rwanda:

Women Hold Up Half the Parliament” in Women in Parliament: Beyond Numbers edited by Julia Ballington and Azza Karam. (Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). http://www.idea.int/publications/wip2/upload/Rwanda.pdf - Plan International (2009). Because I am a Girl. The State of the World’s Girls 2009: Girls in the Global Economy (Woking: Plan International)