Editor’s note: James Parker volunteered with Southern African Wildlife College’s (SAWC) ranger division from June to September 2015. During his time at Kruger National Park, he worked with rangers-in-training.

The two white rhinos are grazing in the grass, about 50 metres away. They are not really that hard to track, as they leave a distinctive hoof print or “spoor,” wherever they go. On the “approachability” scale, the rhino is rather passive compared to most other animals in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. As well, and to the benefit of the poachers, it is a full moon — what’s known as a “Poacher’s Moon” — this evening, making it easier to track the animals in the dark.

The three Mozambican poachers are on tenterhooks though, as they know there are several special ranger-insertion teams in the park at any one time, and, like the poachers, these rangers are expert trackers who have dog-tracking and airborne teams to help them. The poachers move slowly and quietly into position, downwind of the rhinoceros. One poacher is armed with a heavy-calibre rifle, another with a saw and third man with a backpack to store the rhinoceros horn.

All of a sudden, and just as the poacher is about to bring up his rifle to the firing position, a horrendous noise splits the night air and a brilliant light shines down on the three poachers from above. A ranger air operations helicopter team has been dispatched to the poachers’ location by members of a ground team who have been tracking them on foot, with the help of a dog team.

The war on rhinoceros

There is a war being fought in South Africa, and many other African countries, that has nothing to do with race or land or politics. It is a tough and dirty war, based solely on greed. It is known as the “poaching war.” For many thousands of years, Asian societies and others have followed the mystical and ancient beliefs that animal parts have magical and health-redeeming properties. A longer life and stronger libido are only two of many effects they believe come from their ingestion. In traditional Chinese medicine, ground rhinoceros horn is the main ingredient in An Gong Niu Huang, which users believe combats gout, rheumatism and various fevers. In powder form, it is dissolved in boiling water and drunk when cool.

Other animal parts remedies include lion-bone wines, pangolin scales and sea turtle oil. In fact, some estimates put the number of animal species being used in this manner worldwide at more than 1,000. Sadly, despite these “cures” being strongly debunked by the scientific community, the demand for these products is as strong as ever.

The result? These products are more valuable than gold. A kilogram of rhino horn, for example, currently sells for at least $65,000, making it more precious than gold at current rates. Whole underground and illegal economies exist to promote and traffic these animal products with alleged healing powers. These illegal activities in South Africa, for example, continue to successfully exist, almost solely due to pervasive corruption at the highest political levels, down to municipal police, the judiciary and private reserve and national park rangers.

Although subsistence poaching is often used as an excuse, it forms only the tiniest percentage of the overall amount. The vast majority of rhinoceros poaching is done to supply the Asian rhinoceros-horn market, with 83 percent of poachers coming from Mozambique, the country that actually shares the boundaries of Kruger National Park and Limpopo National Park with South Africa. In fact, whole villages in Mozambique depend on this illegal activity as their main industry and source of income. There are clear and worn paths crossing over the border, as indicators of how rife this activity is. Only recently have agreements between the two governments been created to allow Kruger Park authorities to pursue Mozambican poachers back into their own country and extradite them.

Until fences are resurrected between the two parks and the South African army’s presence is beefed up along the border, the problem of Mozambican poaching will continue unabated. (A 2002 treaty between South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe created the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. To make it easier for animals to roam across a now-enlarged habitat, some fencing was taken down.)

Human smuggling organizations, drug cartels, village syndicates and rebel soldiers (who lop off horns and tusks and trade them for arms) are the main players involved in rhino-horn poaching and smuggling. Opportunism exists as well, with amateur poachers coming into Kruger National Park during the time of a full moon to try their luck. Professional poachers, meanwhile, track and kill the rhino at any time of day, night or year. It is not hard to pick out a poacher in his village or town. He is the one with the brand new SUV or the fancy home. He can make $20,000 on a single successful hunt.

South Africa is home to an estimated 18,000 white rhinos and between 1,700 and 1,800 black rhinos. The country does not specify how many of those killed last year were white or black. However, black rhinos are so endangered and valuable that a permanent armed watch of rangers is placed on them. The official number of rhinos poached in 2014 in Kruger National Park was approximately 880, but unofficial numbers show that figure as well over 1,000. The fact that even a few rhinos survive these atrocious attacks is due to the hard work of dedicated ranger and veterinary staff, as well as volunteers such as myself. New medical methods to keep injured animals alive are evolving all the time and include grafting elephant skin onto the horrendous wounds left behind after the rhino horn is removed. However, with limited resources for such a huge area — Kruger Park is almost 20,000 square kilometres, making it larger than Israel, Wales or the state of Connecticut — the current war is not being won by the good guys.

Kruger National Park has approximately 500 rangers employed in various capacities. They range from air operations, special tactical teams and covert and overt teams to dog-tracking teams, intelligence operations and regular patrols. As well, the South African Army has units permanently placed in Kruger, who work in conjunction with ranger staff. It is an ongoing war and technological research make up an important part of the anti-poaching tool kit. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), ultralight aircraft, GPS tracking, motion sensors, infrared and forensics are a few examples of technology being successfully brought to bear against the poacher. In some private parks and reserves, outside-the-box thinking has owners trying techniques such as injecting poison into rhino horns. Others have been painting horns with permanent dye. The bottom line, however, is that these methods are time-consuming and inefficient. Further, in most cases, poachers do not care if their products are poisoned or painted.

The war on poachers

The most important component of all the anti-poaching resources is the ranger. In South Africa, most rangers now are being trained at the Southern African Wildlife College’s (SAWC) ranger division, which is located in Kruger National Park. As well, many African countries are sending their personnel to SAWC’s ranger division or asking the division to send personnel to train and select their rangers.

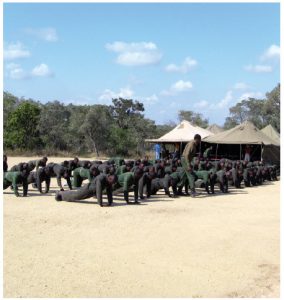

Formerly a private company called “African Ranger Training Services,” owned by Ruben and Marianne de Kock, the business was purchased by and absorbed into SAWC three years ago and is now managed as an academic entity by the de Kocks. Approximately 900 ranger trainees and returning rangers from South Africa’s many national and private parks and reserves are processed through the ranger division every year on a number of different courses. These include basic ranger training, patrol leader, man tracking, advanced tactical training, reaction-force training and special operations. On the basic course, over several months, students learn about forensics, man tracking, small-arms, air operations, conservation, flora and fauna, animal tracking and dog handling. All of this is offered in a paramilitary format and local and South African students do not pay fees or tuition.

As one can see, fighting this war requires extensive resources. And, at this time, despite the manpower and the measures being applied, the war is being lost. Watching and participating in the training, I experienced a sense of urgency in the instruction and the training of the student rangers. They are up at 5:30 a.m. doing physical training (PT) while singing their wonderful African songs, which are, perhaps, slightly less wonderful at that hour when one’s tent is nearby. They are still working at the end of the day, often well into the evening. A normal day in the camp, which is constructed similarly to one in which they would live, will consist of physical training, several periods of lecture-format classroom instruction, real-world training in the bush, including tracking and animal identification, parade-square drill, as well as short periods for meals, which are taken at an outdoor galley. The ranger training camp itself is one-and-a-half kilometres away from the main campus and is thus surrounded by electric wire, as we are in Kruger Park. Almost daily, on trips back and forth between the two campuses, I would see elephants, giraffes, zebras and warthogs grazing and moving about. It was like being on my own safari.

The trainees and returning rangers live in communal tents, eat outside in a traditional, oval-shaped dining area and do their laundry in outdoor tubs. Even some of the showers are outdoors. This style of living prepares the trainees for life on this terrain, where they will spend much of their time serving as qualified rangers in a park. Some patrols, especially when on a chase, can be a month in length. For this tough, dangerous and dirty job, rangers earn approximately $400 a month.

On patrol

His UHF radio crackles at 3 a.m., so the section ranger knows it is something important — and likely not good. A report from patrolling rangers comes over the airwaves to the section ranger telling him of a poacher incursion into their section of the park. He gets dressed and goes to his office, where he radios air operations. He gives the standby aircrew the co-ordinates provided to him by the tracking ranger team and asks that they pick him up on the way. He knows there will be a tracking dog team on board, as well.

Next, he goes to the arms lockup, taking his 7.62-calibre R2 rifle and grabs his “go bag,” which contains freshly charged radio batteries, ammunition, a first-aid kit, snacks and the paperwork necessary for the operation. He goes outside to where the standby ranger team has its quarters and warns them of possible pending action. By the time he has completed his preparation, the helicopter is hovering overhead. It lands on the marked grass pad and the section ranger climbs on board. The pilot, using his night vision goggles, flies only a few hundred feet above the grassland known as the veld. The airborne team reaches the co-ordinates of the awaiting team, where the helicopter lands and quickly picks up the section ranger, the dog and its handler. It lifts off again, staying in touch with the team through UHF radio, and is vectored toward the poachers, approximately two kilometres away.

Tension is high as the ground teams move toward the poachers and the endangered rhinoceros. After only minutes of searching, the pilot spots the three poachers and although they try to escape, he pins them with the aircraft’s powerful spotlight. He directs the ground teams to the poachers, who, this time at least, drop their weapons and raise their hands.

Too often, poachers fight back against the rangers, and these firefights kill rangers and poachers alike. With rangers having only the legal authority to fire back in self-defence, they are at an extreme disadvantage. It is a dangerous occupation for poachers as well, with Reuters news service suggesting approximately 500 Mozambicans have been killed in this fighting since 2005. The ratcheting-up of tensions is due to the incredible value now placed on rhinoceros horn. This is exceptionally sad, as we know the horns are made of the protein called keratin, also found in fingernails and hair, which scientific research has found to be medicinally ineffective.

The week I left, at the end of August, four rhinos were killed and poached and there were 42 park incursions from suspected poachers. This impacts us all. There are humanitarian, moral, financial and ecological implications as a result of poaching. To see a rhino still alive and suffering horrendous pain from having its horn and much of its face removed by poachers is a sight never to be forgotten.

What can Canadians do?

Why should we in Canada and North America be concerned about South Africa’s disappearing rhinoceros? Because they, like all creatures, are part of the biosphere that supports life on Earth. Poaching, overfishing, clear-cutting, strip mining and polluting are all detriments to the biosphere. In other words, our own greed is killing us.

Since 1976, a trade ban on rhino horns under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has been in effect, passed by most countries in the United Nations. However, non-signatory nations still trade horns and some signatory nations continue the illegal trade. “Demand has been steadily increasing in recent decades,” according to the International Business Times, and “the market has exploded to satisfy insatiable demand in parts of Asia, especially in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Japan and China.”

And if one adds elephant ivory to the equation, the United States is the second largest importer of this illegal substance in the world, after China. In September 2015, the two countries agreed to phase out import and manufacture of ivory. The U.S. allows the use of ivory that existed before the global ban in 1989, which is a distinction often difficult to determine. According to a 2014 report quoted in National Geographic, if the ivory trade continues unabated — more than 100,000 African elephants were killed between 2011 and 2014 — some researchers predict that in one or two decades, the African elephant will be extinct in the wild.

A Journal of Ecology study by Joris P. G. M. Cromsigt and Mariska te Beest highlights some of the indirect, yet important, effects the rhino-poaching crisis will have on the African landscape. “Not only is rhino poaching threatening the species’ conservation status,” they write, “but also the potentially key role of this apex consumer for savanna ecosystem dynamics and functioning.” And this is just one species in a specific location. Up to four rhinos daily are being poached in Kruger Park alone or four to eight percent of the population yearly. The impact on the African continent will be horrendous if this treatment of the animals continues unchecked. These statistics don’t take into account lost tourism dollars and impacts on other industries.

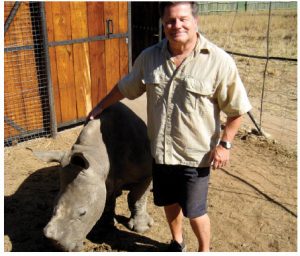

What to do? Volunteers are welcome in many parks, reserves and sanctuaries. For example, I have been volunteering for the Southern African Wildlife College (SAWC), for the past few months and while there, I visited the nearby “Care For Wild Africa,” a wonderful rhinoceros sanctuary. When I visited, it was maxed out, caring for 25 baby and young orphan rhinoceros. Students from Britain and Australia were on site to help Petronel Nieuwoudt run the sanctuary.

If you cannot find yourself heading to Africa to help, there are many charities, although one should be cautious and circumspect in choosing which to support. “Rhino Man” is one I can personally endorse as I met founder Matt Lindenberg at SAWC. The money raised by this group goes directly to the education and training of rangers at SAWC. Even stating your support of anti-poaching by signing petitions on social media can help the cause. Discussion forums, talking with friends, taking part in rallies and not purchasing items from countries that allow the use of rhino horns and elephant tusks are several ways one can help.

James Parker is a retired member of the Canadian Forces. He served in Sudan and Afghanistan. The focus of his second book, titled I Am Ranger, is on the anti-poaching war in Kruger National Park in South Africa. He lives in Victoria, B.C.