“America’s retreat from the world is no longer abstract — it has delivered Syria… to Moscow and Iran’s mullahs, probably for generations. The strategic defeat is only exceeded by the moral defeat.” — National Post, Oct. 5, 2015

The world is changing quickly and not in our favour. The strategic balance has been moving steadily away from the liberal democratic West, where we believed it was firmly and permanently planted since the end of the Cold War. We have become soft in an age in which hardness rules.

Shifts in the balance of power are natural occurrences. But the current dramatic erosion of western power has been accelerated by a striking lack of leadership and moral courage.

Western leadership adrift

The United States became the unquestioned leader of the Free World after the Second World War. In the post-war period, the NATO Alliance owed its success to the political leadership and the military strength of the United States. American armed force stood between an often belligerent Soviet Union and the militarily feeble democracies of Western Europe.

But things have changed. The demise of the Soviet Union, the eastward march of new democratic states and the steady enlargement of NATO and the European Union created a sense of comfort and complacency in Europe and its trans-Atlantic allies. Europeans felt secure and in little need of traditional military forces. Defence budgets were cut and armies reduced. At the same time, the American people had become tired of shouldering the West’s defence burden.

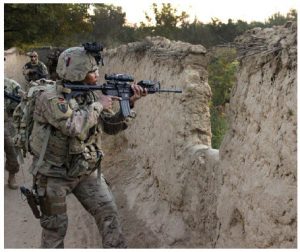

The U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are widely regarded in the West as failures. Complacency was complemented by a sense that we cannot influence events in far distant places, nor should we. This further eroded the ambition and the will of the Americans to lead, and of their closest allies to follow.

The return of hard power: China and Russia

The Obama administration was elected in 2008 by an electorate weary of the burden of international leadership. President Barack Obama promised the United States and the world a new era of reasonableness and compromise with even the most extreme and unreasonable adversaries. So great was the hope and the expectation that the president, hardly into his first term, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009.

But diplomacy without a strong underpinning of military power does not work in a world of rising strategic rivalry. China’s growing economic and military power, coupled with its sense of historical humiliation, much like Russia’s, has led to a new and aggressive approach to its neighbours and a determination to end the ”hegemony” of the United States.

But China is probably a longer-term threat, a vast ocean away.

Much nearer to home, the clear and present danger is a resurgent and aggressive Russia. Years of high oil and gas prices, combined with a steady stream of western technology and investment, have created a huge reserve of cash that has fuelled a renewed sense of power and prestige.

The rise of Putin

The great changes of the early 1990s, following the demise of the Soviet Union, brought a host of political, moral and economic benefits to nearly all the nations of Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Except for Russia. Russia lost its empire, and with it, much of its national pride.

Some members of the Russian elite welcomed the prospect of a new and prosperous future as a Western-style democracy. But the great majority of politicians and military and security leaders, as well as many ordinary Russians, were left with a deep resentment over their new status as a third-rate power. This was compounded by what many Russians saw as the condescending attitude of a victorious West, determined to push its ideas and its alliances further and further east.

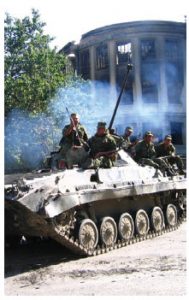

In the year 2000, Vladimir Putin became president of Russia. Almost overnight he swept away the “modernizers” and moved quickly to bring power back to the centre. He crushed the more independent-minded republic governors and those newly rich oligarchs who dared to oppose him. He also brutally ended the rebellion in Chechnya.

Many ordinary Russians, fed by government-dominated media and encouraged by a resurrected nationalist state church, enthusiastically supported Putin’s strong leadership. A young and dynamic leader was, at last, bringing an end to years of deprivation, humiliation and drift.

In the meantime, the United States and Europe were preoccupied elsewhere. Russia had almost disappeared from the international strategic calculus. The war on terror and asymmetric warfare, first in Iraq, and then in Afghanistan, were the order of the day. Russian annexation of parts of Georgia in the summer of 2008 shook this mood of detachment, but only temporarily.

During this period, Russia’s new oil and gas wealth was increasingly funnelled into rebuilding its demoralized military. New and more efficient units were being created and a massive investment in modern armaments was under way that was largely ignored by western politicians, the mainstream media and the public.

Syria: an unlikely battleground

Obama and his inner circle clung tenaciously to the belief that “unreasonable” leaders could be coaxed into sensible compromise in the cause of a peaceful and harmonious world. The violent and depressing results of the Arab Spring and the outbreak of civil war in Syria should have shattered that illusion.

Despite President Bashar al-Assad’s ongoing slaughter of thousands of his own citizens, the United States and its European allies were loath to arm and train opposition forces. The chaos in Libya following the overthrow of President Moammar Gadhafi and the fear of becoming entangled in another Middle East war, especially with an opponent backed by Iran and Russia, was enough to deter Obama from active intervention on the side of the “moderate” rebels, when it might have counted most.

The Obama administration tried to camouflage its lack of resolve in Syria by a proclamation of “red lines,” which could only be crossed by Assad at the peril of direct U.S. and allied military intervention. The clearest red line of all was a prohibition on the use of chemical weapons against opposition forces.

On Aug. 21, 2013, a sarin gas attack by the Syrian government on the Damascus suburb of Ghouta killed hundreds of innocent people. The world waited for a strong U.S. response. U.S. aircraft were ready to destroy Assad’s military infrastructure. But days of prevarication and indecision followed. In the face of veiled Russian and Iranian threats and loud domestic and international opposition, Obama and the tireless Secretary of State John Kerry agreed to a Russian proposal that Assad dismantle his aging chemical weapons stockpile; in return the U.S. called off military strikes.

The sense of disbelief and disappointment amongst the U.S.’s Arab allies, and many others around the world, was palpable.

At a stroke, Obama signalled that he was not prepared to use his overwhelming military might, even in the face of open aggression against friends and allies. It was a clear signal to Putin that his Georgian adventure could be repeated with little risk of a firm U.S. response.

The action soon moves closer to home

The hesitant U.S. and European reaction to the Russian annexation of Crimea and its thinly disguised military intervention in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 proved that Putin was right. He was pushing against an open door.

Deprived of strong U.S. leadership, German and French leaders pleaded with Putin for an agreement that clearly implied an acceptance of the new status quo, including the annexation of Crimea.

It was abundantly clear that Putin was not impressed by strong NATO declarations, token military exercises, puny and fragile sanctions and “non-lethal” support to the Ukrainian army. As a result, there is almost no chance that the Ukrainian government will ever regain real sovereignty over the eastern part of its country, let alone Crimea. The Minsk agreements between the Europeans and the Russians bear a striking resemblance to Munich 1938.

The next disaster: the Islamic State

The rise of the Islamic State, first in Iraq and then in Syria, filled a vacuum created by the premature withdrawal of American forces from Iraq. U.S.-trained-and-equipped Iraqi troops crumbled in the face of a small but determined enemy.

Ironically, this situation was seized upon as an opportunity for Obama to regain credibility after his failure to deter and then to react to Russian aggression in Europe. Bombing what seemed to be a ragtag force with no aircraft and no effective air defence was a relatively risk-free operation designed to show the world that the U.S. and its allies, including Canada, were no pushovers.

Unfortunately, Putin arrived, unexpected, in Syria, too. Having been surprised and outmanoeuvred by the Islamic State, the United States and its allies were again caught off guard by Russia’s latest strategic chess move.

Although the end result of Russian intervention in Syria is far from decided, at a stroke, Putin secured Russia’s only Mediterranean naval base, rescued a murderous ally and established for itself a decisive role in the region in alliance with Syria, Iran, Hezbollah and with Iraq, a supposedly close U.S. ally.

The U.S., along with its regional partners Turkey, Israel, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, scrambled to reach an accommodation with Russia in Syria. And Iran, soon to be relieved of the burden of international sanctions negotiated away by the ever-hopeful Kerry, has openly joined the ground war.

Canada’s opportunity

Despite a strong economy, vast natural resources and a high opinion of our own international importance, Canada has played an almost unnoticed role in these events. Like our European friends, we waited for an American lead. But that lead has largely gone. And countries such as Britain, Germany and France are not prepared, and probably not able, to step into the breach.

The Conservative government’s condemnations of Putin, Assad and the Islamic State provided short-lived hope that Canada might set an example to the West by announcing a strengthening of our armed forces due to the growing threat. Instead, we talked the talk without walking the walk. And, we continued to cut defence spending and military readiness.

It is a standing joke that despite our strong rhetoric, Canada spends only one percent of its GDP on defence, half the very modest NATO goal of two percent, which itself is probably far from enough in this new strategic environment.

During the autumn election campaign, defence issues and the deteriorating world security situation were hardly mentioned. Certainly no political party was prepared to propose an increase in defence spending, even if its members believed it was necessary, which they probably didn’t.

Symbolic of our lack of long-term strategic vision and political courage was the Harper government’s reluctance, amidst the howls of opposition, to move forward on the F-35 program. The F-35, despite its teething troubles, will be the West’s only aircraft that can defeat Russian and Chinese fifth-generation stealth fighters.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised that the new Liberal government will not buy the F-35, despite saying earlier that he favoured a “fair and open competition.” Trudeau has also announced that Canada will end its small, but symbolically important, contribution to the air campaign in Iraq and Syria. The intention, announced in the Liberal government’s first speech from the throne, to create a “leaner” military was a pretty clear indication that defence spending will be further reduced, in order to fund higher priority election promises. These are not encouraging signs of a far-sighted and robust foreign and defence policy.

Of course, Canada cannot play a leadership role in confronting the growing danger to the West. But our government could set an example that even the Americans might notice. First, however, we need to be open and honest with the Canadian people about the dangers of the deteriorating international security situation and the reasons we need to substantially strengthen our armed forces.

Reversing the slide

It may not be too late to reverse the West’s decline. Our massive economic strength, mobilized behind a strong military buildup, would soon outpace the Russians and, as it did at the end of the Cold War, probably wreck their already fragile economy. It would also serve as a salutary notice to the Chinese.

At the end of the day, events will almost certainly force the United States, Canada and the West to dramatically strengthen their defence capabilities. NATO’s recent Exercise Trident Juncture, its largest sea, land and air manoeuvres in a decade, is a good start. But restoring deep and credible military capability in a fast-moving world can be a painfully slow process and events will certainly occur more quickly than we can react. For that reason, the time to start is now.

Western nations have the technological, industrial and the economic capacity to deter or defeat Putin and his friends. But we need clear-eyed and determined leaders to mobilize public opinion and to reverse our dangerous decline before it’s too late.

If we don’t move quickly, we risk losing many of the benefits we’ve gained since the time of the Cold War. More ominously, as demonstrated by the recent downing of a Russian aircraft on the Syrian border, we could be caught, dangerously unprepared, for a real shooting war with a resurgent and self-confident enemy.

Richard Cohen is president of RSC Strategic Connections and a senior associate with Hill+Knowlton Strategies. He was a senior adviser to defence minister Peter MacKay and he was a career soldier in the Canadian and British armed forces.