As it happened, Ronald C. Rosbottom, a professor of French culture at Amherst College in New England, was in Paris on Jan. 7, 2015, the day of the terrorist attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo. A bit of bad luck, one might say, but perhaps a bit of good luck as well, for Rosbottom is the author of When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940–1944 (Hachette Canada, $31), a social and political history of the city’s takeover by the Nazis. There are, of course, a number of fine books on this subject. Rosbottom’s distinguishes itself by relying not only on memoirs and official documents, but also on the pop culture of that time and place, including movies, songs, drawings, posters and the like. If satirical publications such as Charlie Hebdo had existed in Paris 76 years ago, Rosbottom would be putting them to good use now.

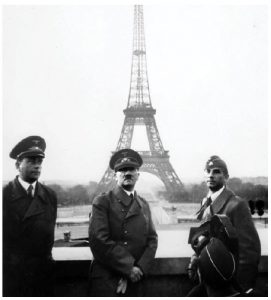

We all should remember the broad outlines of what happened in June 1940. Having already overrun territories elsewhere in Europe, the Germans pointed their claws westward, with the ultimate goal of vanquishing Britain and then attacking North America. They easily broke through the Maginot Line, the series of fixed fortifications that the French had erected as though the Great War and the Spanish Civil War had taught them nothing about air power. To put the matter concisely, the Nazis essentially just rolled into Paris (strolled, one might almost say), seemingly acting as much like flâneurs as conquérants. No shots were fired, and many Parisians welcomed the Nazis with cheers and huzzahs (while others joined the underground Resistance movement). Hitler himself arrived in Paris, a place whose cityscape even he had always admired. He had his picture taken with the Eiffel Tower, the way people do. He also visited Napoleon’s tomb — of course.

For the first two years or so of the Occupation, daily life in Paris went along more smoothly than anyone had a right to expect. The city was full of soldiers, of course. Most of them made up the new garrison of 20,000, but others used Paris in somewhat the way American troops used Bangkok and Hong Kong during the Vietnam War: as a respite from combat, in this case combat with the Russians on the Eastern Front. They were issued booklets showing how to navigate the Métro and how to deal with the locals (who, for their part, had pamphlets with tips for avoiding difficulties with the Germans). This odd period of mutual unease, which Rosbottom calls “the Minuet,” began to unravel seriously in September 1941 when food rationing was instituted. From that point onwards, the situation quickly turned very dark indeed.

Not all of France was held by the Nazis, at least not officially or all at once. Their Occupied Zone took up nearly all of northern France and the entire Atlantic coast from Spain to Belgium. Southern France was the Free Zone, also known as Vichy France after the city that served as the seat of the Nazis’ puppet government. Vichy was formed in 1942 (and shared the map with a chunk of the country taken over by the Italian fascists). By that time, the persecution of Jews had worsened by calculated increments. Jewish businesses had to display yellow signs reading Entreprise Juive. Then Jews were forbidden to own or even manage businesses, to study in universities, to practise law, medicine and the other professions or to own a radio or a bicycle. Their bank accounts and safe deposit boxes were confiscated, and then the truly terrible part got under way.

Not all of France was held by the Nazis, at least not officially or all at once. Their Occupied Zone took up nearly all of northern France and the entire Atlantic coast from Spain to Belgium. Southern France was the Free Zone, also known as Vichy France after the city that served as the seat of the Nazis’ puppet government. Vichy was formed in 1942 (and shared the map with a chunk of the country taken over by the Italian fascists). By that time, the persecution of Jews had worsened by calculated increments. Jewish businesses had to display yellow signs reading Entreprise Juive. Then Jews were forbidden to own or even manage businesses, to study in universities, to practise law, medicine and the other professions or to own a radio or a bicycle. Their bank accounts and safe deposit boxes were confiscated, and then the truly terrible part got under way.

Deportation of Jews begins

Working with Vichy police and militias, the Nazis began deporting Jews en masse in a series of rafles or roundups. At the end of June 1942, Adolf Eichmann arrived in Paris to commence “the final solution.” In August 1944, the Russians and the western Allies, including Canadians, of course, fought their way into Paris from opposite directions and les années noires came to an end — in fact, but certainly not in memory. Not even remotely.

Rosbottom introduces himself to the reader by saying he does not “claim the mantle of historian but rather of storyteller and guide.” This is fair enough, but overly modest. He does a fine job on his primary task of re-creating the rhythms of Parisian life during the 50 months of German rule. To do so, he must also write about the French underground guerrilla movement that rose up in the city and throughout the nation, driving the Nazis mad with bombings, sabotage, assassinations, booby-traps and other such activities. He must likewise deal with the Free French government-in-exile that Gen. Charles de Gaulle, the future French president, ran from London. All these are highly controversial topics in France to this day.

The bitterness and rancour took hold the moment the Nazis were driven out. A few days after his triumphal return, de Gaulle, who led his own forces in the Normandy invasion, addressed a huge crowd of Parisians from the city hall steps. He said: “Paris liberated! Liberated by its own efforts, liberated by its people with the help of the armies of France, with the help of all of France.” To put it mildly, he withheld praise for the Americans, the Russians and the others who did the heavy work, and minimized the contribution of — indeed the very makeup of — the underground resistants.

The bitterness and rancour took hold the moment the Nazis were driven out. A few days after his triumphal return, de Gaulle, who led his own forces in the Normandy invasion, addressed a huge crowd of Parisians from the city hall steps. He said: “Paris liberated! Liberated by its own efforts, liberated by its people with the help of the armies of France, with the help of all of France.” To put it mildly, he withheld praise for the Americans, the Russians and the others who did the heavy work, and minimized the contribution of — indeed the very makeup of — the underground resistants.

When the Nazis got serious about their occupation, they encouraged people to give them the names of fellow citizens who were invisibly assimilated Jews or anyone who was thought to be undermining German authority. Citizens spread lethal gossip and squealed on one another, often for purely personal motives. The Nazis gathered large numbers of suspects who would never be heard from again. In the Southern Zone, such people were dealt with by the Vichy police (who, in a 1942 purge called Le Grand Rafle, rounded up Jews as young as two years old).

The nation had been humiliated when the French army was overrun so easily. (Just before the war’s end, there were still 1.5 million French PoWs being held in camps in Germany.) When France was free again, the search was on for civilians who had taken the easy road and helped the Germans in various ways, large and small. De Gaulle called them “a handful of scoundrels,” but that was hardly what they were. Some of the totals are almost unbelievable. By the autumn of 1943, 85,000 French women had children fathered by German soldiers. Even women not accused of such collaboration horizontale, but only of mild fraternization, had their heads shaved by angry mobs who then paraded them through the streets. (They were the lucky ones.) Male collaborators of various sorts were frequently just shot in the head by veterans of the resistance.

Underground tales

Almost at once, people who felt at least sheepish and more likely totally humiliated by the way they’d been dominated began to create a glorious folklore around the brave Resistance veterans. Every so often as the years rolled on, someone would challenge the accepted version of almost-universal French bravery, and the wound would be reopened again, as happened in the 1970s, for example, with the French film, The Sorrow and the Pity. In recent years, many francophone authors (such as François Boulet or Philippe Bourrin), as well as anglophone ones (Ian Ousby or Robert Gildea), have written fresh revisionist books on the subject. Gildea, an Oxford professor, has written more than one, in fact. His latest is Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance (Harvard University Press, US$35).

Gildea’s argument, in brief, is that just as Charles de Gaulle downplayed the number of Nazi collaborationists, so too did he distort the size, composition and workings of the resistance movement, which was also called the Maquis (after a tough Mediterranean shrub). De Gaulle’s retrospective version was that the movement included a significant percentage of the population when, in fact, Gildea writes, the most widespread civilian response to the occupation was an attitude of attentisme (“wait-and-see”). In de Gaulle’s mind, or vision, very nearly all resistants were French nationals — and male. Forty thousand young French men — 80 percent of them under the age of 20 — did take part, but worked and fought beside economic migrants and Jewish refugees from much of Europe, British behind-the-lines experts from the Special Operations Executive and, most of all, hardened veterans of the Spanish Civil War, a highly cosmopolitan bunch indeed, including communists, liberals, unaligned anti-fascists and, of course, just plain adventurers. One would look hard to find stories of greater bravery than some of those in Gildea’s books.

Fighters in the Shadows is full of documents, including rosters of many who served and came to sad ends at the hands of the Nazis. A great number of the brave and noble ones — to judge from Gildea’s narrative, a disproportionate percentage — were women, many of whose tales will make you weep. De Gaulle did his best to ignore their sacrifices. Only three years ago were two of these resistantes permitted to be buried in the Panthéon, the traditional final resting place of France’s greatest heroes. One of them was Geneviève de Gaulle. One wonders to what extent her late uncle would have approved.

Why is the above so important? With the terrorist attack on Paris on Nov. 13, 2015, still ringing in our ears, the top-selling, most controversial and serious new book in France is Soumission, by one of the country’s most famous and important literary figures, the novelist and poet Michel Houellebecq. The image on the front is the fated issue of Charlie Hebdo. Houellebecq’s English-language publisher wasted no time in confirming that his company would push ahead with plans for publishing an English translation by Lorin Stein. It is available as you read this (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $32). The book is set in a France under Islamist rule. It is fiction. Let’s keep it that way.

The search for intelligent intelligence

I’ve always been wary of books written “with” someone besides the purported author. An example is The Great War of Our Time: The CIA’s Fight Against Terrorism from Al Qa’ida to ISIS by Michael Morell (Hachette Canada, $31). Morell is now a consultant and network television explainer. Prior to that, he was variously acting director or deputy director of the CIA, following Leon Panetta, who departed to be secretary of defence, and David Petraeus, who left in a sex scandal. The book is written “with” Bill Harlow, a former CIA public relations executive. So what we get here are snippets of Morell’s autobiography, complete with school graduation pictures, and a not ill-informed defence of the agency’s workings. Morell believes “more can and should be shared with the American people about what the agency does every day” because popular culture creates distorted impressions. He calls one of these pop-cult stereotypes the Jack Ryan myth (that the agency is invincible). Others are the Get Smart myth (that the agency is incompetent) and the Jason Bourne myth (that it is a rogue operation with its own extra-governmental agenda). All of these, Morell naturally says, are false.

Afghanistan adieu

One thing Morell’s book does do is to boldly imply, and yet in a between-the-lines sort of way as though the notion weren’t obvious, that we’re stuck not in a series of disconnected wars, but a single continuous one against an enemy with numerous names and many theatres of operation. Each new episode in the sequence takes control of our attention, allowing us to almost forget the previous ones. One of the virtues of Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan to a More Dangerous World by the British journalist Christina Lamb (HarperCollins Canada, $39.99) is that it vividly recounts and analyses the opening salvo of the allied invasion of Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks and tracks the consequences through the next 13 years, getting to know nearly everyone — Afghan, American and British — of any importance. In doing so, the author genuinely comes to love the people and the culture in ways that few male correspondents seem to have done. She reminds one of Gloria Emerson of the New York Times, who had such a relationship with Vietnam, publishing a wonderful book about it called Winners and Losers, and then committing suicide in 2004 when Parkinson’s disease prevented her from writing more.

Lamb quotes a famous remark by Harold Macmillan, the British prime minister (1957–63): “Rule number one in politics is never invade Afghanistan.” This statement arose from the crushing British defeats there in the 19th Century, but the Russians failed to heed the advice in the 20th. Lamb’s experience reporting the late stages of the Soviet fiasco in the 1980s prepared her to cover the American and allied invasion that began a month after the Twin Towers were destroyed. Her observations about the leaders of the western military and, to a lesser extent, the Afghan bureaucracy, are caustic, but never smart-alecky — just bizarre. The British defence minister of the day confessed he couldn’t locate Afghanistan on a map. Afghanistan’s energy minister was dubbed the “minister of darkness” because there were often long stretches without electric power. The U.S. spent more than $3 million for patrol boats to police the coastline of a country that is landlocked. And so on. “How on Earth,” she asks, looking back, “had the might of NATO, 48 countries with satellites in the skies, 140,000 troops dropping missiles the price of a Porsche, not managed to defeat a group of ragtag religious students led by a one-eyed mullah his own colleagues described as ‘dumb in the mouth’?” Not that she hated the westerners. Rather, she had come to love the Afghans and their culture.

Rethinking wars — again

An American academic, Dominic Tierney, whose résumé includes Oxford, the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard and the Foreign Policy Research Institute, takes a bold view of American strategy (and to some extent diplomacy) in The Right Way to Lose a War: America in an Age of Unwinnable Conflicts (Hachette Canada, $31). His thesis is this: Given that future wars are likely to be unconventional, dirty, low-down and regional or even local, and thus not susceptible to the long-held U.S. military patterns and procedures, it might be time to rethink — once more — participation in other people’s civil wars and regional conflicts.

With the exception of the Gulf War of 1991, the U.S. hasn’t had a clear victory for 70 years. It has seen, however, several somewhat productive stalemates, as in Korea. The subtitle of Tierney’s previous book, How We Fight: Crusades, Quagmires, and the American Way of War sums up his viewpoint neatly. To avoid being sucked into quagmires, Washington should open with a big surge, and once having made the point, negotiate a workable agreement that falls short of either outright victory or outright defeat, and then go away (though of course the other possible exit strategy — wise when possible — is never to leave home in the first place).

And briefly…

One of the subplots in Spectre, the most recent James Bond film, has to do with the idea of merging MI5, the British domestic intelligence service, with the international one, MI6. This struck me as odd until I read John Le Carré: The Biography by Adam Sisman (Knopf Canada, $36). For it turns out that Le Carré (real name: David Cornwell), the author of such thrillers as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, belonged to both agencies (though not at the same time). Then, there are spies we’ve never heard of who keep suddenly turning up from the past. The Ingenious Mr. Pyke by Henry Hemming (Publishers Group Canada, $33.99) concerns a brilliant inventor and financier who came up with the notion of a combined U.S.-Canadian special forces group in the Second World War, but turned out to be a highly placed Soviet agent. The Baroness Moura Budberg was a famous Russian author (and other things) in the Bolshevik period. Her own bizarre story is told by Deborah McDonald and Jeremy Dronfield in A Very Dangerous Woman: The Lives, Loves and Lies of Russian’s Most Seductive Spy (Publishers Group Canada, $29.99).

George Fetherling is a novelist and cultural commentator.