The history of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada begins much earlier than any other group living here — and is far more complex. When European settlers arrived in what would become Canada in the early 16th Century, the number of aboriginal people ranged from an estimated low of 350,000 to as high as two million. By Confederation, more than 350 years later, the aboriginal population had not grown, as might be expected, but had shrunk dramatically. In 1867, there were between 100,000 and 125,000 First Nations people here, along with about 10,000 Métis in Manitoba and 2,000 Inuit across the Arctic.

The reasons for their decline are tied to such factors as war, illness and starvation, arising directly from European settlement and habits. As The Canadian Encyclopedia notes: “The aboriginal population … continued to decline until the early 20th Century.” Even after that trend reversed, other problems continued, including discrimination, ignorance or misunderstanding of aboriginal cultures, and government laws and policies that often had disastrous effects.

Those challenges and hardships cannot be forgotten and National Aboriginal History Month is an opportune time to remember them. Yet, it is also important to be aware of the achievements of Aboriginal Peoples and the manner in which they have enriched the lives of all Canadians.

At our organization, Historica Canada, we highlight the triumphs and tragedies involving Aboriginal Peoples in Canada through programs such as Aboriginal Arts & Stories, The Canadian Encyclopedia and our Heritage Minutes. Any list of events in either category is certain to be incomplete, but the process is ongoing. Here are some stories on which we’re working: One new Heritage Minute, released on June 21 (National Aboriginal Day), chronicles a tragic story arising from the long-standing forced enrolment of aboriginal youth in residential schools.

A second new Minute released in June depicts a treaty negotiation through the eyes of aboriginal people, who saw the process in much different terms than their counterparts across the table.

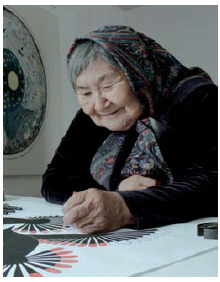

A third new Minute, for release this fall, tells the story of Kenojuak Ashevak, the world-renowned artist who was at the forefront of the global popularization of Inuit art.

Some other past minutes tell stories of aboriginal traditions and defining events. They include: Aboriginal achievements during the War of 1812 (many while in alliance with the British), particularly at the Battle of Queenston Heights; the heroic life and troubled death of Tommy Prince, one of Canada’s most decorated military figures; the hanging of the still-controversial Métis leader, Louis Riel, in 1885; and a Minute devoted to the significance of the Inukshuk, the Inuit symbol that serves as a statement in the wilderness to declare, as one character says, “now the people will know we were here.”

Those efforts barely even scratch the surface of Aboriginal Peoples’ history in Canada.

At the same time, it’s worth noting the wide range of peoples that the term “Aboriginal” encompasses. As of 2010, the most recent year for which statistics are available, the term included: 617 First Nations communities and more than 50 nations, eight Métis settlements and 53 Inuit communities. Collectively, that includes more than 60 languages. In the 2011 National Household Survey, the most recent, more than 1.8 million people declared aboriginal ancestry.

All of this goes to show that Aboriginal Peoples in Canada are distinct and diverse, with many different cultures, traditions and lifestyles. Their diversity gives them something in common with other Canadians, in a country increasingly defined by that quality. Yet, at the same time, they are increasingly proud of being distinct. And, more than ever, they are determined to stay that way.

Anthony Wilson-Smith is president and CEO of Historica Canada.