From a prison cell in Abu Ghraib to the ambassador’s office in Ottawa, Abdul Kareem Kaab has had a tremendous career path. A civil engineer by trade, he was jailed and tortured for political protesting during his undergraduate studies and then again after he’d finished his schooling, spending two years in Abu Ghraib. After being released and tiring of the harassment involved in Iraq’s “probation” periods under Saddam Hussein, he fled his beloved country for Europe. After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, he returned and has been working as a diplomat since 2009. He arrived in Canada in March and sat down with Diplomat’s editor Jennifer Campbell to speak about his experiences and his aspirations for Iraq.

Diplomat magazine: What is life like in Iraq today?

Abdul Kareem Kaab: Iraqi people are normal Mediterranean people. They are heavily family-oriented people and they spend a lot [of time] enjoying life. We have a huge number of students and we have workers who want to go to their work stations, whether factories, farms or offices. The streets are full of traffic, people. Our restaurants and shopping malls are full of people. Iraqis are very generous, hospitable and brave people.

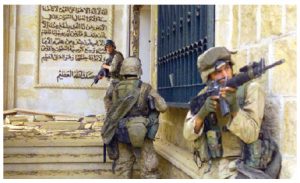

But after the bringing down of the tyrant Saddam and his regime, we had the attack from international terrorism that melded with Ba’ath and Saddamist people — criminal people, very dangerous people — and we got a devilish marriage that nowadays we call DAESH [ISIS in the west.] This [group] is targeting Iraqi civilians. So now, from time to time, you see suicide bombers, car bombs hitting schools, markets and some public buildings — much less now than before 2014, thank God. This has influenced the situation and left its marks on day-to-day life. You see concrete walls and barriers to protect public places, you see checkpoints and you see armed security forces, whether from the army or Iraqi police. This is Iraq.

DM: What does Iraq want from Canada?

AKK: Our diplomatic relations go back five-and-a-half decades. And we have [in Canada], a huge number of Iraqi-Canadians. After 2003, there’s a new chapter with Canada and Iraq sharing the same political views and humanitarian principles and values, such as the belief in democracy, peace and respect for human rights. The fourth factor, after 2014, is that Iraq and Canada have joined the counter-terrorism war to eradicate DAESH in Iraq. Now there are Canadian military personnel and equipment in Iraq and we’re working together. So, [given] this, Iraq expected Canada to have a large, functioning embassy in Baghdad. That means a sufficient number of diplomats and commercial attachés, a visa section, a military attaché and a residing ambassador in Baghdad. [Instead,] we have a military attaché in Baghdad and one diplomat, but there may be as many as seven or eight by the end of this year.

Also, Iraq expected that Canada, as a friend and ally, would provide more aid for Iraq’s displaced people after the occupation by DAESH of our four provinces in 2014. Now that we are liberating the Fallujah region, we have thousands of displaced families who are desperately in need of immediate aid and shelter. Also, because of the very difficult economic situation we are facing, especially after the fall of oil prices and the huge cost of the war, we were expecting Canada to encourage Canadian companies to invest in Iraq by providing guarantees and financing. This would be of great help for sustainable development of Iraq.

DM: It’s kind of a hard sell to Canadian business. It’s very risky, wouldn’t you agree?

AKK: No, many provinces have been very safe since 2014 and we have many international companies from all over the world working there — very big companies, including Shell, Nokia Siemens Networks, Huawei. So it’s not risky. And we haven’t faced any attacks against international investors or companies.

DM: What you’re describing — regular suicide bombings and ISIS attacks — appears to have its roots in the same old Sunni-Shia rivalries. What can the government do about that?

AKK: We must first ask when this started and why. It started after 2003. It wasn’t immediately after. It was when Iraqis decided to have a free, democratic country believing in human rights. That was the start of this. Some mistakes were made by the American administration of Iraq at that time, especially [dissolving] the sovereignty of our army and police forces. That opened the door widely for international terrorism to want to come to Iraq. It was the Ba’ath Saddamist people and, regrettably, they are heavily supported by regional factions. This problem started back then.

Iraqis have real multiculturalism in our blood, so we accept each other and we have lived with each other since our first days on Earth until 2003. This is a continuation of the attack against the Iraqi people by the former regime’s criminals.

Our government has been doing its best to counter this, but, regrettably, because of the mistakes made by the American administration [concerning police and security forces], we don’t have good, functional police or security forces and it’s very difficult to build that when you’re under attack. Having said that, they are doing their best, and what we’re seeing now, in the ongoing battle to liberate Fallujah, [is part of their efforts to address this.] Fallujah, the base of these terrorists, is only 60 kilometres south of Baghdad, so it’s easy for them to send suicide bombers from there. This is one of the reasons to liberate [Fallujah.]

Iraqis are truly multicultural, so we should conclude that Iraqis genetically reject the ideology of these terrorists. The ideology or mindset of these terrorists is not tolerance or acceptance. If someone isn’t from the branch of their beliefs, they call him kafir [infidel] and that means they consider him a non-believer. They give themselves the right to kill him, to possess all his properties — his wife, his children, his farm. This is not the Iraqi way of thinking.

In 2014, after the formation of the PMF [the People’s Mobilization Forces, a state-sponsored umbrella organization made up of 40 militias, most of which are Shia] we became sure that ISIS would be eradicated in Iraq. Now, I’m confident, after the remarkable work we are doing in Fallujah, we will see the fall of ISIS. The question is when. This depends on the second source that nourishes ISIS. First, there’s the ideological side, but the second is the material side — the manpower, financing, arms and ammunitions. These aren’t made by them, they’re imported. There are huge recruitment movements all over the world. There’s a very effective financial network.

DM: It’s interesting how Iraq’s internal factions have altered the way countries have chosen to allign with different sides. Does this concern you?

AKK: A point will come, and I see it now, that DAESH will fall down and the players supporting them, whether regional or international, will get tired. They cannot go on forever.

DM: Was George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq reasonable?

AKK: In 2003, the U.S. troops, as the head of the international coalition, liberated the Iraqi people from the tyrant Saddam and from his criminal, racist, unjust, repressive regime.

DM: That sounds like a yes.

AKK: Since 2003, Iraqis are really enjoying freedom of speech, freedom of religious or political affiliation, beliefs. We have a huge number of newspapers, magazines, TV channels. [Almost] all are [independently owned]; only one belongs to the government. No one can force Iraqis to fight long, absurd wars for nothing anymore. They now have freedom of movement to live where they want in Iraq, and externally. Iraqis’ incomes have multiplied many times, so they have freedom to live and travel. If you go to the Baghdad airport, you’ll see how busy it is — [it’s Iraqis] seeing the world.

After 2003, the unjust sanctions have been lifted, which gives us the freedom to enjoy our fortune and wealth.

One can criticize the American administration at that time, maybe over the huge destruction [of infrastructure] to bring Saddam down, and the dissolving of the army.

DM: But overall, you’d say it was good?

AKK: Yes.

DM: You had a personal experience with Saddam in that you were a prisoner at the notorious Abu Ghraib prison. Can you talk about that?

AKK: Yes. I was a political prisoner. I was one of thousands of Iraqi young people who were opposing, just opposing, Saddam’s way of thinking. I couldn’t accept the injustice I had seen, or the racial discrimination against Iraqis, the oppression of people and worshipping a very bad man. Iraqis were like slaves. We lost almost one million [citizens] in the first Gulf War. I was also involved in projects to help the families of political prisoners.

My first imprisonment was in 1979. I had participated in one protest against Saddam in Baghdad and I was captured and tortured. This is normal practice. They brought me to the highest court — “the revolution court.” For months, my family and friends didn’t know if I was alive or dead. This was my first year in university, so I was maybe 20. That started the new life for me, [one where I was] harassed by police forces [after I was released.] I had to go and register every week — I was on probation. I had to tell them where I was going, what I was doing and how long I was staying. I had no right to a passport.

During the coup of Saddam, in the summer of 1979, he became the tyrant, absolute dictator after he killed 22 leaders of Ba’ath. And he killed the former president and his son. He wanted to make a show so he released some prisoners and killed some others. I was released. I had been in there for months.

I lived with my father and brothers and sisters, but people at the university and in my city were very careful about having relationships with me.

In 1984, after having just finished

university, I was captured again. The accusation was that I was helping the families of political prisoners. I was tortured for months and no one knew where I was. There was no right to a lawyer and no right to contact your family. I was sentenced to 10 years and I spent two years in Abu Ghraib. In 1986, there was a special amnesty issued by Saddam. I and 1,000 others enjoyed this amnesty and it was the same life [with respect to probation.] They took me from the prison to the army and that was my amnesty. They wanted to kill us by making us fight in the Iran-Iraq war [1980-1988]. They sent me to the front lines without any weapons.

After that, I had many problems because of being in prison. My right hip joint was destroyed, so I became an unarmed soldier. I spent three years in the military as an engineer, because I was a civil engineer after university.

DM: You’re very lucky to be sitting here.

AKK: Yes. After the army, I went into civilian life. I had no fixed address, so I could get away from the harassment, but I didn’t always succeed and they caught me many times. After the Iraqi uprising of 1991, I went back to prison for three months and some days [I lived with] 100 people from Baghdad. [Saddam] thought we were dangerous. By 1994, I had three children, so I decided to flee the country and join the diaspora. I went to Arab countries for three years, then to Germany for eight years and got German citizenship. Then I moved to London. After 2003, I went back to Baghdad. In 2009, I joined the foreign ministry. I was at headquarters for one year, then became ambassador to Finland and Estonia for three years, then I returned to Iraq for three years and came [to Canada].

DM: Other than the fact that Iraq is very multicultural, what would you tell westerners that they don’t know about Iraq?

AKK: They should know we have multi-religions, we are not one ethnicity. This means that the brotherhood of mankind, all people, is in our blood. Iraq is more than an oil well. It’s not [merely] a huge market for western and other products. It’s more than that. Iraqis have suffered a lot, for decades. [They suffered under] the tyrant Saddam and his absolute authoritarian regimes for years, then the wars, and under the international sanctions and their huge effects on vulnerable Iraqi people, especially kids. We lost a lot of our people because of that. Then the war to get rid of Saddam and what has happened after that, we feel we’ve been left alone, facing our [lot]. We haven’t [received] tangible enough aid from international players. Having said that, Iraqis remain positive about their future in the international arena. We have forgiven the people who didn’t come to our rescue. [The world] should know the blood and bravery of Iraqis can stop DAESH.

DM: Is a world without ISIS likely any time soon?

AKK: We have to ask where DAESH is now. [They are in] Iraq, Syria, Libya and some other places. Regarding Iraq, our way of thinking genetically rejects DAESH’s way of thinking, so it can’t last there. The question isn’t whether we’ll get rid of them, but when. That depends on the material sources — arms, ammunitions and funding. Syria also has a promising future, especially now that the Syrian army is approaching the capital of DAESH. They are also a cradle of civilization and a multicultural nation.

DM: What are your hopes for a peaceful democracy in Iraq, and if you believe it’s coming, what’s the timeline?

AKK: We lived ages, since 1960, under authoritarian regimes. We didn’t have civil society institutions. Then, immediately, we got real democracy. The transition period, normally, takes time. In Iraq, I think our time will not be long and in the last year, we have real positions in the parliament, huge, peaceful demonstrations in Iraq. No one uses weapons between Iraqi blocs and factions. We have a peaceful transition of power. [Democracy] is there now, but not mature.

There is huge pressure from the people, the religious leaders and politicians to address corruption. One bloc in parliament is really insisting on a radical solution for that. The new prime minister, [Haider al-] Abadi, has pledged to counter corruption and he has done a lot, but there is more to be done.

One of the signs of the good job they’ve done is the professionalism and success of our security forces — army, PMF, police forces — how they’ve dealt with the terrorism. The ISIS people had occupied almost 50 percent of our territories in 2014, now they occupy less than 30 percent. The security forces are much better than before.

DM: Is the Shia community susceptible to the same trap it fell into in 2006, when al-Qaeda in Iraq struck a sacred Shia shrine and ignited a sectarian civil war?

AKK: I don’t think so because they are very controlled now. The PMF, at the beginning, was only Shia and these people [fought for] Iraq. International terrorism reached the gates of Baghdad in 2014. These people [PMF] pledged their souls to defeat terrorism. They are very controlled now and they are doing what the prime minister asks. Their main job is to liberate the Iraqi territory and support the security forces and they are very good fighters.

It isn’t fair to call them militia because they are disciplined and their behaviour is very controlled. Their allegiance is to Iraq. They should be returned to the civilian life after this, though some may join the military forces. These days they’re fighting together with Sunnis and also Turkmen [who are also traditional Sunnis].

DM: How long should the West keep helping and why? When you’re talking to Foreign Minister Stéphane Dion, what is your best pitch for help?

AKK: We are allies, firstly, and we share the same political views. We expect [Canada] to help Iraq through its political, economic and military difficulties. Defeating DAESH is the easiest one. It’s almost finished and I will celebrate the end of DAESH when they liberate Fallujah. Mosul is not that big a deal.

We expect aid for the internally displaced millions. They lost their houses, jobs and farms. They desperately need help. We need our friends to help us to build a functional, diversified economy. We need investment and a push from the government for business to take advantage of the huge opportunities in Iraq. The government just has to start it moving.

It’s not that easy to rebuild a whole country. We are also looking for help from our partners or friends. Helping us to have a unified country is also important.

DM: What is your prediction for the next year?

AKK: We will be liberated from DAESH. I can’t say 100 percent when, but it’s for sure finished. We will concentrate more and more on political issues and how to run the country successfully. Between 2003 and now, it hasn’t been that successful, but we are much more serious now. The government has promised to reduce spending, fight corruption, but there is much more to be done. Next year, [expect] a more unified country, and politically, I think it will be much better.

DM: The Iraq as we know it is an artificial state in a way, created after the First World War. Did the British get it right?

AKK: It was actually the first state in the world. But you’re talking about the current borders. This is a problem for Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran. It has caused problems with neighbours. Water issues, for example, and some border issues. [The British] didn’t do it very well. But I think there’s no way to rethink it now. It’s too dangerous. You open a door, you can’t re-close it. Not just for Iraq and the region, but for the whole world. It’s a reality.