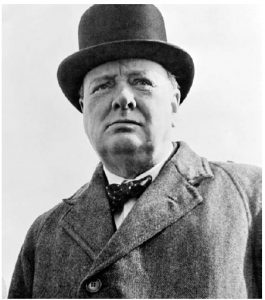

In 1929, Winston Churchill, who was then the chancellor of the exchequer in Stanley Baldwin’s government, was making a tour of Canada and the U.S. In a speech in Vancouver on Sept. 23, he said, “We see Canada growing in every way — education, civilization, numbers and wealth.” That was the day prices on U.S. and Canadian stock markets reached their absolute pinnacle. Barely a month later, on Black Thursday, Oct. 24, the New York Stock Exchange collapsed like a cheap card table, sending concussions around the world.

As luck would have it, Churchill was on Wall Street that day, watching from the visitors’ gallery high above the trading floor, and was quickly hustled out of the building. When, a short time later, he was struck by a New York taxi while crossing the street, he cabled a newspaper editor in London offering to “produce [a] literary gem about 2,400 words” describing the accident in exchange for some quick cash. Churchill, the minister responsible for Britain’s financial affairs, the man who, by returning Britain to the gold standard, probably helped to create the atmosphere in which the great crash inevitably came about, needed money — quickly. He almost always did, throughout most of his long life.

The at times almost unbelievable story of Churchill’s stunning financial incompetence is the subject of No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money (Picador, US$32). David Lough, a London private banker with a historian’s skills, is able to tell it now because although Churchill was almost psychologically incapable of saving money, he did save everything else, including bills, receipts, bank statements, tax records, cancelled cheques and all other financial papers, which his descendants have now agreed to open up to researchers. What the documents reveal is routinely astounding. For example, Lough writes that a few days after the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg and were poised to take France as well, Churchill, the brand-new prime minister, “had to confront another unpleasant truth closer to home: he was running out of money to pay his household bills and his tax or the interest on his large overdraft, which was due at the end of the month.”

So he did what he had done two years earlier. He asked his parliamentary private secretary, Brendan Bracken, to clean up the mess — discreetly, of course. Bracken called once again on Sir Henry Strakosch, a mining magnate, banker and co-owner of The Economist who, apparently asking nothing in return, wrote a cheque for what today would be £250,000, payable to Bracken, who then endorsed it over to Churchill. That makes the question of a $90,000 cheque in our recent Mike Duffy scandal seem like a trifling affair. But this sort of thing was a thread throughout Churchill’s career. He had expensive tastes in everything from real estate to wine to silk underwear and was an inveterate gambler at race tracks, casinos — and brokerage houses. In 1922, he frittered away the equivalent of £90,000 at the gaming tables in Monte Carlo and Biarritz. His losses in the great stock crash that he saw taking place in 1929 “would have exceeded £8.9 million in today’s money.” He said, “It excited me so much to play — [I was like a] foolish moth.”

The insolvency gene

Maybe Churchill’s money problems began at his birth. As ill luck would have it, his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was the second son and so didn’t inherit Blenheim, the palace and grounds that Queen Anne had bestowed on the Churchills’ ancestor, John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, in 1704. By late Victorian times, the estate had been whittled down considerably, helped by the fact that Winston’s father was himself a spendthrift. So too, in a lesser way, was his mother, who said that, at 13, her son was spending enough for a normal family of six or seven. “You do go through it in the most rapid manner […] and the more you have the more you want to spend” — as he later did on polo ponies and race horses, for example. So he joined the army.

In that period, it was not unheard of for young officers to moonlight as foreign correspondents. Churchill found he could write easily, and voluminously, and so began to sell — first to Fleet Street editors and later to book publishers — the stories of his military adventures in Cuba, the India-Afghanistan border, the Sudan and South Africa. A book about the last-named place, From London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, brought him the modern equivalent of £400,000 and enough fame to let him enter politics. That was another field of endeavour in which he enjoyed taking chances — as when, during the Great War, he orchestrated the disastrous Gallipoli campaign against the Turks, which resulted in a slaughter for which Australians have never forgiven his ghost.

By the time that war began, he was already an oenophile who spent what would now be £100,000 a year on wine and spirits (plus a great deal on cigars, a habit he had picked up in Cuba). In 1930, for example, he had to write three books and more than 40 articles just to keep up.

Lough shows us the actual ledger pages. Churchill was aware of his excesses and scrawls the warning “No more champagne” on one sheet. On another, he scribbles “Cigars must be reduced to four a day” (not for health reasons, but for budgetary ones). Yet he couldn’t stop himself — nor, one supposes, did he really wish to. As he climbed the political ladder step by step, he was descending into ever greater debt, and would routinely delay payments to tradesmen — shirtmakers and watchmakers, to take two examples — for years, even decades. He “avoided tax with great success,” Lough writes, and to keep from drowning, borrowed more and more and wrote more and more. Eventually, his numerous books, and sometimes the sale of film rights to them for movies that never got made, eventually left him rich indeed, as in the case of his wartime memoirs, which he produced using enormous piles of secretly borrowed government documents and the help of ghostwriters when necessary.

But the process of enrichment took many years, during which he was forced to turn his hand to whatever he could — the freelancer’s dilemma — such as doing a bit of lobbying on behalf of the petroleum interests and, at one point, agreeing to write a booklet to accompany a jigsaw puzzle about great battles of the world. Financially, his darkest days were his years in the political wilderness leading up to the Second World War and then the war itself and its immediate aftermath. The irony here is that the saviour of his nation couldn’t seem to save himself. In 1938, 1940 and 1946, he again had to seek wealthy admirers to keep from actually going bankrupt.

But the process of enrichment took many years, during which he was forced to turn his hand to whatever he could — the freelancer’s dilemma — such as doing a bit of lobbying on behalf of the petroleum interests and, at one point, agreeing to write a booklet to accompany a jigsaw puzzle about great battles of the world. Financially, his darkest days were his years in the political wilderness leading up to the Second World War and then the war itself and its immediate aftermath. The irony here is that the saviour of his nation couldn’t seem to save himself. In 1938, 1940 and 1946, he again had to seek wealthy admirers to keep from actually going bankrupt.

No More Champagne is a cautionary tale certainly. But it’s also an absolutely riveting book about economics. And how often do you find one of those?

Spending more time with the family

Political memoirs concerning the nine years of the Harper government haven’t begun to surface yet, but if one listens closely one can hear pens (and heads) scratching. Instead, for the time being, we have one from the other camp and an earlier time: The Call of the World (UBC Press, $39.95) by former Liberal cabinet minister Bill Graham, who rode high in the Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin governments, particularly as foreign affairs minister from 2002 to 2004 and then, until 2006, as defence minister. The American journal Publishers Weekly, which is always the first to review new books (anonymously), tore into this one as bland, cautious, long-winded and pompous: a work that “never lives up to its lofty title.” That hasn’t been my impression of it.

Graham seems to me quite straightforward, mostly sincere and sometimes even candid. As even Publishers Weekly had to admit, he isn’t above admitting to a big mistake: “I regret that I — and the Chrétien, Martin, and Harper governments — were not more aggressive in pushing to get Omar Khadr,” a Canadian citizen, freed from the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

True, Graham doesn’t come off as a room-filling personality. Rather, he paints himself as a successful lawyer who entered politics relatively early and worked hard at it, winning all but one of his five contests in the riding of Toronto Centre (formerly called Toronto-Rosedale). His primary focus became “diplomacy, always trying to reduce the heat and increase the light,” and it can’t be denied that he held the foreign affairs portfolio at a dangerously interesting time.

Living with the elephant

Considered as a narrative — a story full of turns and twists — the most intriguing part concerns Chrétien’s refusal to join in the American invasion of Iraq, which is, of course, widely acknowledged as the source of much of the world’s strife and terror today. Graham had a solid working relationship with Colin Powell, his U.S. opposite number, who was duped by the George W. Bush administration into telling the United Nations that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. He quotes Powell as saying later: “Bill, you have no idea. I threw out boxes and boxes of stuff they tried to get me to say. I was briefed by our intelligence people with mountains of crap.”

The U.S. ambassador in Ottawa sent Graham an order, not a request, straight from the Oval Office, to be relayed to Chrétien personally: “The prime minister of Canada needs to say something nice about the president of the United States, in public, soon.” Chrétien replied that Canada would not join the war without a UN resolution. That was in March 2003. By the end of the year, Chrétien was out as PM, destroyed by the sponsorship scandal. Graham had somewhat less regard for the new leader, Paul Martin, but displays a great deal less than that, shall we say, for Jack Layton, the NDP leader who brought down Martin’s minority government in February 2006 (whereupon Graham did a turn as his party’s interim leader).

The Call of the World includes a good deal of interesting information about the nuts and bolts of electoral politics in this country and how they are changing. The author’s old riding includes Rosedale, yes, but also cheap and even slummy highrise housing whose residents are often difficult to reach, or don’t speak English, or are connected to their iPods and iPhones to the extent of being disconnected from, and uninterested in, the world and its news. Another interesting portion of the book describes an incident during the 1997 election in which an LGBTQ newspaper was considering outing candidate Graham as gay. “This had been a concern of mine since deciding to enter politics in 1984, but my family [including one son who covered the Iraq war as a correspondent] and I had always endorsed the idea that the state had no place in the bedrooms of the nation.” He says little else about the matter. Which, for a book published in this year of grace 2016, seems unnecessarily secretive and coy.

Diplomatic manoeuvres

Here’s something not often encountered any longer: an example of bipartisan co-operation in the United States. Robert D. Blackwill was an adviser to George W. Bush and Jennifer M. Harris was an adviser to Barack Obama. True, both are now members of the Council on Foreign Relations, yet even so it seems striking that they should have collaborated on War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (Harvard University Press, US$29.95) — the title of course a play on Carl von Clausewitz’s aphorism that “war is the continuation of politics by other means.” Their thesis is that the American government must do more strategic investing in other nations it fears are becoming suspiciously stronger. China and Brazil, for example, “have lending portfolios that outstrip the World Bank’s. More than half of global development aid comes from the EU and its member states, but depends upon fulfilment criteria.” Even Canada, they point out, has “actively sent aid and development-minded investment dollars into countries identified as having resources of interest to Canadian firms, including Mongolia, Peru, Bolivia, Ghana and even the conflict-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo; it smacks of corporate welfare for some critics, of crass commercialism for others. But they [that is, we, not the Mongolians or the Congolese] are taking Canadian standards with them.” The quotation is from one of the authors’ 20 “policy prescriptions.”

Cold War Games: Propaganda, the Olympics, and U.S. Foreign Policy by Toby C. Rider (University of Illinois Press, US$24.95 paperback) is a particularly fascinating piece of diplomatic history. By mining obscure archives and gaining access to previously classified documents, Rider is able to show how, beginning in the late 1940s, the U.S. manipulated the governing body of the Olympics by, for example, rigging the selection of host cities and trying to shift the games’ focus away from pure athleticism and toward anti-communist agitation, even to the point of recruiting Eastern Bloc exiles to help weaken Soviet influence.

Of course to be fair, one must say that Moscow had its own countervailing goals and schemes. We don’t need to be reminded that such tactics were simply part of the tenor of the times. For example, both sides used musicians and composers as evangelists of their respective ideologies. At one point, even chess masters were put to work this way. An oblique reminder of the tone of those days is Garry Kasparov’s new book, Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped (Publishers Group Canada, $33.99). Kasparov was the top-ranked chess player in the world when he retired in 2005 to play a rather more dangerous game as leader of an anti-Putin and pro-democracy movement. He is now an exile in New York. His book is, to say the least, a forceful statement, full of fury, sorrow and sound reporting.

Finally, a fine book not about diplomacy or even politics, but about racism of a kind. In 1871, Henry Morton Stanley, the journalist and explorer (more the former than the latter) was sent to Africa to find Dr. David Livingstone, who wasn’t actually lost. A few years later, near Lake Victoria, Stanley stumbled upon a group of Africans who seemed to him to have white skin and European features. He, and much of the world, took this as proof of the Hamitic Hypothesis, the crackpot idea that Ham, the son of Noah, in the Bible, settled in Africa and propagated. This hokum about “a white tribe” then spread to other continents, as in, for instance, Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s assertion that he had discovered “blond Eskimos” in the Arctic. Michael F. Robinson may have got the idea for his new book, The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent (Oxford University Press, US$29.95), while researching his previous one, The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture, a work with much to say to Canadian readers. In any event, The White Tribe is a strong rebuke (more are needed) to the foundations of some of the racist thinking in society today.

I’m sorry, but I can’t drop the subject without pointing out that Livingstone died in 1875 and that, when Stanley passed on in 1904, the headline in one of the U.S.’s leading newspapers read “Stanley finds Livingstone — again.”

George Fetherling is a novelist, cultural commentator and chair of the Writers Union of Canada.