In January 2014, I was appointed as the representative for the United Nations refugee agency to Yemen. In this capacity, I was to lead and co-ordinate the protection and assistance services for hundreds of thousands of refugees, asylum-seekers, new arrivals and internally displaced Yemenis.

Two months later, I was asked to assume the functions of the humanitarian co-ordinator for Yemen, in addition to those as UNHCR representative. As the senior-most United Nations official in the country, I was expected to lead and co-ordinate all humanitarian work conducted by UN agencies and international and national NGOs. Little did I know that one year later, Yemen would be plunged into a humanitarian crisis of unprecedented volume and severity.

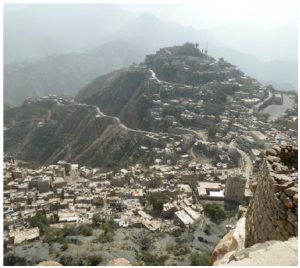

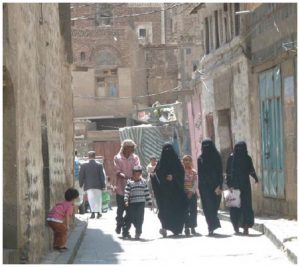

I had always wanted to serve in Yemen. I had heard so many stories of the exotic country, which, in ancient times, was called Arabia Felix. It is marked by a long history, landscapes ranging from mountains to deserts, along with a long coastal strip, unique architecture and, above all, a tribal population that keeps up traditions. I was also interested in seeing how Yemen was dealing with the aftermath of its own version of the Arab Spring in 2011, and how I could now contribute to the transition, one I hoped would lead the country on a path towards inclusive democracy and strengthened rule of law. I also hoped it would modernize the administration and respect for the human rights of all, notably women, youth and a large marginalized segment of the population.

I arrived in Yemen full of enthusiasm and optimism, but soon conflict pushed the country into chaos, mayhem and destruction. My tasks would turn out to be very different from what I had imagined before I arrived.

A country in transition

My first public appearance in Yemen was to attend the closing ceremony of the National Dialogue Conference, which was attended by hundreds of representatives of the political, social and tribal groups in country. These groups had deliberated for a year about the new political landscape and social fabric for the country under the supervision of Jamal Benomar, special adviser to the UN secretary general. The ceremony was a solemn event, bringing together the president, the government, dozens of tribal sheikhs, politicians, female and youth activists, foreign diplomats and donor representatives. I was honoured to be part of it, as it was obvious that history was being written that day.

At least we thought so. Soon after, however, it became clear that the hundreds of recommendations of the conference would not be easily implemented. Moreover, one month after its conclusion, and while the country was preparing for a new constitution and presidential and parliamentary elections, transitional President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi announced that Yemen, in future, would be divided into six regions that would form a new federal state. By not allowing much discussion, the president had hoped that any simmering dissenting forces could be silenced. This proved to be a miscalculation. Demonstrations broke out in the north and the south. While those in the south remained peaceful, those in the north quickly turned violent.

The rise of the al-Houthi

In fact, the al-Houthi minority in the north took up arms to support its wish for more autonomy, investment and development, as the northern region had been neglected for decades during the previous long rule of Ali Abdulah Saleh (1978–2011). The al-Houthi had unsuccessfully waged six rounds of war against the army of the former president between 2004 and 2010, and now they took up arms again. While they had started as a revivalist youth movement representing a religious Shi’ite Muslim minority in a majority Sunni country, the al-Houthi had quickly transformed their struggle into an armed uprising, initially to enforce self-governance and an equal share in the country’s scarce revenues, but soon it became clear that the al-Houthi also had territorial aspirations.

During the first six months of my double-hat assignment, it became clear that the fragile transition period was in serious trouble. The al-Houthi fighters made advances towards the central provinces, ably co-opting the support of tribes that had hitherto been their enemies and, in July, they managed to conquer the important regional city of Amran, which had been known as a stronghold of the Islah party, the Yemeni version of the Muslim Brotherhood and a staunch opponent of the al-Houthi.

I travelled to Amran days after its fall to the al-Houthi to determine the emerging humanitarian needs after the bloody conquest, and to broker sustained, safe access for humanitarian workers and aid supplies. I negotiated for two hours with Abu Ali al-Hakim, the top militia leader of the movement, who was dressed in fatigues. None of us would see him again as he has been fully immersed in the armed struggle ever since.

The summer brought demonstrations in the capital Sanaa, orchestrated by the al-Houthi against the government’s decision to abolish subsidies on fuel and essential commodities and against rampant corruption. The situation was tense, but none of us believed the al-Houthi would capture the capital as the group had no cadre to administer the country.

We were proven wrong, however. On Sept. 21, 2014, the al-Houthi took the capital after two days of localized fighting against militant Islah groups. Ali Mohsen, the commander who had led the army loyal to Hadi subsequently had to flee, as he was known for his Islah membership. I remember vividly chairing a meeting of the humanitarian team while explosions and shelling happened just one kilometre away. It was no reason to suspend the meeting; on the contrary, we urgently needed to put a contingency plan into action and ensure aid reached the parts of the capital under siege.

Once Sanaa was taken by the al-Houthi and the members of the transition government and senior officials supporting them had left their positions, it became increasingly clear that behind the al-Houthi’s successful takeover of Sanaa was former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who, as part of the deal to oust him from power in 2011, had been allowed to stay in the country. Many segments of the army, security forces and administration had remained loyal to the former president and it was those segments that would allow the al-Houthi to exert their power.

From then on, change came quickly. While the secretary general’s special adviser managed to broker a truce and a political settlement, the al-Houthi refused to implement its provisions. Though they had agreed to do so, they didn’t withdraw their militia from the capital, didn’t allow the transitional government to return to power, and didn’t transform their movement into a political party that ultimately could help form a coalition government of national unity.

A technocrat government was formed in November 2014, but it couldn’t govern because in January 2015, the al-Houthis arrested Hadi and the prime minister, and suspended parliament, the constitutional court and all other state institutions. The diplomatic community left the country in February and we humanitarians were the only international presence left (with the exception of a few diplomats from Russia, Iran, Syria and Iraq).

In March 2015, two Sanaa mosques visited mainly, but not solely, by al-Houthi supporters were hit by heavy bomb attacks that caused more than 100 casualties and provoked the al-Houthi into a general mobilization and a rapid military descent to the south. Within a week, they had captured the port city of Aden, the second biggest city in the country and its economic capital. On the way, they had taken Taiz, Yemen’s third-biggest city, and its cultural capital, known for its intellectual activity, and for having been the city from which the uprising against then-president Saleh began in 2011.

Hadi, who had been able to escape from house arrest in to Aden, had to subsequently flee to neighbouring Saudi Arabia, together with members of his government. Ever since, he has been governing in exile.

The regionalization of the conflict

Then came the bombing. None of us had foreseen that Saudi Arabia and a coalition of 10 Arabic states would directly involve themselves in the conflict, adding a regional dimension to it. Yet, in the early hours of March 26, 2015, the coalition started an airstrike campaign to remove the al-Houthi from power and reinstate the legitimate and internationally recognized Hadi government. None of us had foreseen that by the end of 2016, 20 months into the conflict, the situation would be mainly one of status quo with the al-Houthi still firmly in power in the north and central part of the country. Increasingly, the conflict evolved into one in which the Saudis not only wished to reinstate the legitimate Hadi government, but also wanted to reduce the influence of its regional rival, Iran, the avowed supporter of the al-Houthi, though the extent of this support remains somewhat unclear.

Aden and the five southern governorates were liberated from al-Houthi power in July 2015, mainly with the support of the United Arab Emirates. The goal was to reinstate the Hadi government in the south. Yet the volatile security situation, mainly caused by the presence of the jihadist extremist terror groups al-Qaeda and ISIS, has so far prevented Hadi’s reinstatement on a permanent basis.

Ever since the escalation of the conflict, the international community, under the auspices of the UN, has sought a negotiated settlement between the warring parties. A number of efforts, accompanied by ceasefires or humanitarian pauses, have so far failed to bring an agreement on a political solution.

I assisted in some of the peace talks, as a resource person for humanitarian confidence-building measures, and learned that peace and a settlement remain within reach. Yet for this to happen, the parties must demonstrate a minimum level of political will and readiness to compromise. The longer the conflict persists, the more difficult a solution is to reach. Twenty months into what started as an internal conflict, the dynamics have changed and the conflict is increasingly about regional hegemony, securing the oil trade along the Red Sea and fighting terrorist and jihadi groups. The Yemeni people are the victims of a conflict that counts no winners.

Leading the humanitarian response

Shortly after the start of the airstrikes campaign, the situation became extremely volatile, with the risk of a complete breakdown of law and order. There was also talk of an armed invasion over land. The humanitarian community decided to leave, except for a core team that would stay in the country to co-ordinate the emergency response. I was in charge of this operation and after the departure of more than 100 UN and NGO staff, including the special adviser and his team, as well as remaining embassy personnel, we stayed behind with 10 international humanitarians.

Unfortunately, after a few days, it became imperative that we also evacuate as our safety and security could no longer be guaranteed. A plane took us to Addis Ababa and then to Amman, where each UN agency and international NGO established a Yemen backup office. I remember the emotions of guilt and frustration when we had to leave our Yemeni colleagues behind.

The exile was bitter, but of relatively short duration. The humanitarian crisis caused by the conflict had rapidly deepened and it was decided that, provided the necessary staff safety and security measures were put in place, the humanitarian community should return to the country to address the exponentially increased needs. After six weeks, I returned, leading a small core team of 10 staff. A UN air shuttle to and from Djibouti was set up and today still serves the humanitarian community. Initially, we stayed in the basement of one of our offices in the capital, which had turned into a ghost town, littered with garbage and waste and marked by shelling and airstrikes. We then moved into a heavily fortified hotel where we would live while witnessing the nightly airstrikes. During the day, we would move in armoured vehicles to our offices. While we were happy to be back, the severe restrictions on our freedom of movement and the extremely volatile security conditions required high levels of resilience. We had to leave our private accommodation; I missed my house and garden, as well as the escorted visit to the supermarket, which used to be the highlight of each weekend.

Yet at least we were back in the country and I could assume the leadership of a significant operation. The escalation of the conflict had resulted in a humanitarian emergency of unprecedented scale and volume.

Prior to the escalation, Yemen already had a humanitarian crisis, with more than 15 million of the 27 million Yemenis in need of some form of external aid. Following the escalation, this number rose to 18.8 million people in need — 70 per cent of the population. These needs stem from years of poverty, under-development, environmental decline, intermittent conflict and weak rule of law and governance. Now we must add devastating conflict to that list. Of those in need, more than 10 million are in acute need today, urgently requiring immediate life-saving assistance.

A protracted humanitarian crisis

Between 2012 and 2015, real gross domestic product per capita fell by just under 50 per cent, from $590 US to $326 US per capita, and by almost 35 per cent in 2015 alone. Inflation has risen by 30 per cent. The conflict has led to wilful destruction of infrastructure worth an estimated $19 billion US, the equivalent of half Yemen’s GPD in 2013. The poverty rate has doubled to 62 per cent. Parties to the conflict have targeted key infrastructure such as ports, markets, roads, bridges and factories with airstrikes, shelling and other attacks.

Yemen is dependent on imports for more than 90 per cent of its staple food and its energy supply is also mainly dependent on imported fuel. However, restrictions on imports as a result of an arms embargo imposed by the UN Security Council, coupled with the destruction of port infrastructure, have resulted in a severe reduction in the supply of food, fuel and medicines.

The current conflict, the severe economic decline and the regularly imposed restrictions on imports and transport contribute to serious shortages and price increases in basic commodities. Millions of Yemeni struggle to make ends meet these days. Purchasing power has fallen substantially as livelihood opportunities are diminishing. The relocation of the Central Bank of Yemen from Sanaa to Aden has contributed to a liquidity crisis. Civil servants and their families — a third of the population — are no longer receiving salaries and letters of credit for vital imports are no longer issued to traders. The Central Bank foreign exchange reserves have dropped from $4.7 billion in late 2014 to less than $1 billion in September 2016.

The already threadbare basic services have suffered further from the current conflict and a considerable number have collapsed. As of October 2016, only 45 per cent of the country’s health facilities remained functional. An estimated 14.8 million Yemenis have no access to basic health care. The conflict has resulted in the destruction of or damage to at least 274 health facilities. Functioning health facilities reported more than 44,000 casualties, including more than 7,000 deaths since the escalation of the conflict. An average of 75 people are killed or injured each day. These are conservative figures as health facilities have diminished reporting capacity.

The conflict has resulted in a 10-fold increase in the number of internally displaced within a year. As of October 2016, nearly 2.2 million people remained displaced, of which more than half are in just three of the 21 governorates. Three out of four displaced persons are living with host families or in rented accommodation; the remainder are in “collective centres” or in the open. More than one million displaced have provisionally returned to their areas of origin during the last few months, with three out of four returning to Sanaa, Aden and Taiz. These returns, however, remain precarious and some people have been uprooted again as conflicts flare up.

An estimated 14 million Yemenis, more than half of the population, have limited access to food, and half of these do not know where their next meal will come from. The country has seen a drastic decline in agricultural production, which normally employs half of the population, as a result of conflict, insecurity and lack of seeds, fertilizers, transport and markets. The fishery sector has seen a 50-per-cent decline as a result of the conflict. Two cyclones also had a devastating effect in south Yemen in late 2015.

An estimated eight million Yemeni have lost their livelihoods or are living in communities being deprived of minimal basic services. Approximately two million children are out of school and 1,600 schools are currently not in use, either because they have been damaged, are being occupied by armed militia, are hosting internally displaced people, or there are no longer any teachers or learning equipment available. Malnutrition is another problem as 3.3 million children and pregnant or lactating mothers are acutely malnourished, with more than 460,000 children severely malnourished, a 63-per-cent increase since late 2015.

More than 14 million Yemeni do not have access to safe drinking water and sanitation, and this is particularly a problem for the internally displaced and their host communities. A total of 4.5 million Yemeni are in need of emergency shelter and essential household items, including the internally displaced and their hosts. Beyond the material needs, Yemeni are lacking essential protection of their safety, dignity or basic rights. Women are victims of sexual violence, children risk being recruited or married off early; marginalized people suffer discrimination in accessing essential aid. These vulnerable Yemeni are in need of psycho-social, legal and other counselling services.

Forced displacement

The conflict in Yemen has resulted in the flight of more than 90,000 Yemenis,

Somalis, Ethiopians and others to countries in the Horn of Africa. Several tens of thousands of Yemenis are thought to have sought refuge in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. As it is not in the tradition of Yemeni to seek refuge abroad, but rather to find shelter and safety in the villages in the countryside, these numbers are without precedent.

Notwithstanding the conflict, Yemen remains host to more than 260,000 refugees from neighbouring countries, essentially Somali (250,000), many of whom have sought refuge since the collapse of their country in 1991. Other refugee populations include Ethiopians, Eritreans, Syrians, Iraqis and Palestinians. Yemen is the only country in the Arab Peninsula that is signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol. It is also a transit country for economic migrants, and 2016 saw a staggering 100,000 Ethiopian migrants, but also Somali refugees, arriving on its shores.

With partners, UNHCR co-ordinates a large number of protection services for refugees and asylum seekers in the country. With the exception of 20,000 Somali refugees who are hosted in the Kharaz camps in the southern governorate of Lahj, all refugees live in Sanaa, Aden and Taiz where it is somewhat easier to earn a living, though the conflict has also caused significant impoverishment of the refugee population.

UNHCR registers asylum-seekers and refugees and provides them with documentation that should protect them from arbitrary arrest and expulsion. However, 2016 saw a rise in arrests and detentions and subsequent expulsions of mainly Ethiopian refugees, but also Somalis by the al-Houthi de facto authorities, who argue that the refugees would otherwise have joined the militia serving President Hadi.

UNHCR and its partners provide the refugees with psycho-social support, cash assistance for the most in need, support for vulnerable children and survivors of sexual violence, as well as access to health care. Refugee and asylum-seeker children have access to public education at all levels.

Life in the cities is difficult for refugees, who complain of frequent harassment and insecurity, coupled with loss of income as work opportunities in the informal sector have become scarce. The refugee area of Basateen, near the southern city of Aden, was hard hit by heavy fighting during the three-month occupation by the al-Houthi in 2015. This resulted in the self-imposed flight to Somalia of thousands of Somali refugees. Many of these, however, returned to Yemen when the al-Houthi were driven out of the southern governorates.

Life in the refugee camp in Kharaz has been better, as, with few exceptions, the food, medicine, water and energy supplies have not been interrupted. UNHCR and its partners have been able to provide services to the camp-based refugees throughout the conflict. Refugees in both camp and urban settings have organized themselves in committees with elected leaders to provide support and arrange awareness sessions in mental health, family planning, female genital mutilation and other harmful practices. The level of self-management and organization of the refugees in Yemen is high and the UNHCR conducts monthly meetings with leaders to address and respond to problems with documentation, employment opportunities, education or delays in the refugee status determination process.

As UNHCR representative, I oversaw the many projects of the vast refugee operations in Sanaa, Aden and Kharaz camp. With my legal and protection staff, I regularly intervened in cases of arrest and detention. Sometimes refugees in despair staged demonstrations in front of the UNHCR offices in the false hope of obtaining assistance or resettlement to third countries. To peacefully solve such refugee protests required skilful mediation and negotiation. Once, we negotiated the release of a group of more than 200 Eritreans who had been detained upon arrival in Yemen and whose refugee status was subsequently confirmed.

As thousands of Ethiopians and, to a lesser extent Somalis, keep arriving on Yemeni shores, notwithstanding the current conflict and destruction, UNHCR and partners continue to provide them with initial reception such as clothing, food and medical support before they are referred to UNHCR offices in case they wish to seek asylum, or take to the road by themselves in search of work in Saudi Arabia or the Gulf States. UNHCR and its partners are uniquely placed to collect and analyze the data and trends of mixed migratory flows towards and through Yemen. Nowadays, however, the authorities arrest considerable numbers of new arrivals and put them back on boats to Ethiopia. UNHCR and partners are planning an information campaign in Ethiopia and Somalia to dissuade people from going to Yemen where they can expect arrest by authorities and interception and exploitation by traffickers and smugglers.

Being a humanitarian in Yemen

As UNHCR representative, but also primarily as humanitarian co-ordinator, I travelled within Yemen to reach and help the displaced, refugees and the new arrivals. Some areas in the midst of conflict, however, were difficult to reach. Travel took weeks of negotiations with the rebels, but also the coalition in Riyadh as numerous checkpoints had to be passed and local militia had to provide safe passage. Much of this travel was dangerous. I recall checkpoints where illiterate militiamen couldn’t understand our written authorizations and weren’t familiar with humanitarian aid convoys. It required negotiations with the parties to the conflict, the government in exile and the Saudi authorities to ensure the neutral and impartial nature of our humanitarian aid effort would be respected. We also made sure humanitarian partners locally, selected by the United Nations for their expertise, experience and adherence to humanitarian principles, were allowed to do their work. This often proved challenging as authorities frequently prevented local partners from moving around and running their operations.

Negotiating humanitarian access, ensuring the safety of humanitarian personnel and aid and mobilizing sufficient resources from the international community have been, and are, among our major challenges. The destruction of roads and bridges was, and is, another impediment. During my assignment, I saw large-scale destruction in Aden, Taiz and Sa’ada. I saw corpses in the street, children starving and adults severely wounded as a result of the conflict. I narrowly escaped disaster when I was delayed on my way to an area where an airstrike hit at the same time I was supposed to be there. I sweated at checkpoints where illiterate militia had killed those who passed before me, including other humanitarian aid workers. I crossed frontlines with the warring parties within shooting range.

These experiences have left a mark on me, but I was most impressed by the resilience of the Yemeni people and the refugees the country is hosting. I saw the immense gratitude on their faces when long-awaited aid finally arrived. I have been deeply moved by the mutual support and inner strength of my own colleagues when one of them lost a husband, brother or son in the conflict, or, as happened to one of our drivers, 10 members of his family as a result of one airstrike.

Those of us who have served and lived in Yemen know that this experience leaves a lasting impression. Yemen, Felix Arabia, is the most exotic country I have ever called home, and today, it is also among the most severely damaged and destroyed. I have seen human nature at its darkest, but I’ve also seen the bravery and courage of the Yemeni people. I have shared moments of utter despair and utmost relief. The daily bombing still resonates, the destruction and human misery haunt me every day. Yet if I could, I would return to Yemen today, to support the humanitarian response and the search for peace and stability.

Johannes van der Klaauw is UNHCR’s representative in Canada. The views expressed in this article are his and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations.