Like a giant supertanker foundering in stormy seas off a rocky coast, the United Nations requires a strong, firm hand at the tiller, someone who can steer the ship away from the perilous course on which it is now headed.

The new occupant of the White House, Donald Trump, is no fan of the organization, describing it in one of his tweets as “just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time.”

The new Republican-dominated U.S. Congress doesn’t much like the UN either. Some Republicans want to eliminate funding for the organization entirely because they are rankled by the recent UN Security Council vote that condemned Israel for building settlements on the West Bank and in East Jerusalem — a resolution on which the outgoing Obama administration chose to abstain rather than veto.

Those Republicans who don’t want to go that far still want to cut the size of the U.S. contribution or make it voluntary. The U.S. pays almost one quarter of the UN’s total regular budget, which, in

2016-17, amounts to $5.6 billion US. (Canada’s contribution, in contrast, is about three per cent). Any of the reductions being contemplated will have a major impact on the organization’s operations.

Trump has also threatened to withdraw the United States from various UN treaties and conventions, including the recently concluded Paris agreement on climate change. Even if he doesn’t actually formally withdraw the United States from these conventions, there is still a good chance he still may not honor the U.S.’s commitments.

But it is not just the Trump administration threatening the effectiveness and future of the UN. Relations in the Security Council among the five permanent members have been dysfunctional on vital issues of global peace and security for much of this decade. Russia and the western powers, for example, are deadlocked over how to deal with the ongoing crisis in Syria. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have lost their lives in the country’s brutal civil war. Millions more have been displaced. It is the biggest mass exodus of refugees since the Second World War. Syria burns while the UN fiddles.

The UN’s peacekeeping reputation has also taken a hit. UN peacekeepers in Congo and the Central African Republic have been implicated in the widespread sexual abuse and exploitation of minors. UN peacekeepers from Nepal were apparently responsible for a major cholera epidemic in Haiti, which led to the death of many civilians.

Last year, former UN assistant secretary general Anthony Banbury (who was responsible for overseeing the UN’s efforts to deal with the outbreak of Ebola in Africa) published a scathing indictment of the organization in the New York Times. He accused the organization of “colossal mismanagement” and blamed it for shoddy hiring practices, excessive red tape and decisions made on the basis of political expediency. Banbury admitted he was clearly not the first person to point out the UN’s failings, “but too often, these criticisms come from people who think the United Nations is doomed to fail. I come at it from a different angle,” he said, “I believe that, for the world’s sake, we must make the United Nations succeed.”

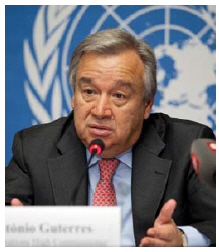

That challenge now falls squarely on the shoulders of the former prime minister of Portugal, Antonio Guterres, who became the ninth secretary general of the United Nations at the beginning of this year, replacing Ban Ki-moon, who had been in the post for 10 years.

Guterres is no stranger to the UN. He served as UN High Commissioner for Refugees from 2005 to 2015 and from all reports did a credible job. The only blemish on his record was a highly critical internal UN audit report about the way the organization managed its finances.

Unlike his predecessor, Guterres is known to be outgoing and a good communicator. In his first address to the members of the Security Council, he talked about the importance of preventing global crises instead of the UN’s usual default mode, which is to “respond” to them. “We must rebalance our approach to peace and security,” he urged. “For the future, we need to do far more to prevent war and sustain peace.”

This is not the first time a UN secretary general has stressed the importance of conflict prevention. It is an all-too-familiar refrain. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who served as secretary general in the early 1990s, urged the same in his much-touted Agenda for Peace. So, too, did Kofi Annan, who tried to develop an institutional “culture of prevention” in the UN. Alas, there has been little in the way of effective conflict prevention and the UN is still very much in firefighting mode on those occasions (increasingly rare) when it decides to act.

One does not have to be a hardened devotee of realpolitik to appreciate the UN’s limitations. Major bodies of the UN and the UN Security Council, which are supposed to stand at the apex of the global security system, are failing to meet the test on the most critical problems of global security. Secretary General Guterres says the challenge now “is to make corresponding changes” to the UN’s “culture, strategy, structure and operations.”

At the top of his list should be reform of the Security Council, which is long overdue. For more than two decades, the open-ended working group on Security Council reform has met to review and discuss different proposals, but there has been only one successful reform of the membership. That was during the height of the Cold War in 1965 when non-permanent membership was increased from six to 10 members. Britain and France, which are both European members and nuclear powers, wield a veto in the council. Some believe that Europe should only have one seat, but if Britain leaves Europe, that argument may be less tenable. It is also highly questionable whether Russia, and indeed China, should be allowed to exercise a veto, especially in light of their recent performance on Syria. Perhaps vetoes should be abandoned in favour of a super-majority plurality.

Japan, Germany, India and Brazil should also become permanent members of the Security Council. These countries are simply too big and too influential to be excluded. Japan and Germany, in particular, are also major contributors to the UN’s operations and budget. There should also be proper representation for those countries that do the heavy lifting in peacekeeping operations and the work of the UN’s specialized agencies.

Guterres will have to be bold and tough if he is going to succeed. What the UN needs is heavy doses of tough love. But that is a tall order and it is also going to have to be directed at the organization’s member states, which are ultimately responsible for many of those very deficiencies and failings that have so enfeebled the UN.

Fen Osler Hampson is co-director of the Global Commission on Internet Governance. He is a distinguished fellow and director of the Global Security & Politics Program at the Centre for International Governance Innovation. He’s also Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University.