I have a framed poster on my wall at home that illustrates 14 different types of small explosive devices. The same poster is found in nearly every elementary schoolroom in Laos (and Cambodia, too) where it’s intended to teach the little ones to refrain from, for instance, playing with landmines. My copy hangs above the kitchen table to remind me how lucky I am to live in a place where peace is the norm. The poster is also, in its way, a small memento of what started out as Operation Momentum, but became an enormously destructive land and air war that was kept a secret from the people who were paying for it. This event is the subject of A Great Place to Have a War (Simon & Schuster Canada, $37). Its author is Joshua Kurlantzick, whose previous book, about the strange disappearance of the presumed American spy Jim Thompson was reviewed enthusiastically in these pages a while ago.

I have a framed poster on my wall at home that illustrates 14 different types of small explosive devices. The same poster is found in nearly every elementary schoolroom in Laos (and Cambodia, too) where it’s intended to teach the little ones to refrain from, for instance, playing with landmines. My copy hangs above the kitchen table to remind me how lucky I am to live in a place where peace is the norm. The poster is also, in its way, a small memento of what started out as Operation Momentum, but became an enormously destructive land and air war that was kept a secret from the people who were paying for it. This event is the subject of A Great Place to Have a War (Simon & Schuster Canada, $37). Its author is Joshua Kurlantzick, whose previous book, about the strange disappearance of the presumed American spy Jim Thompson was reviewed enthusiastically in these pages a while ago.

Operation Momentum and the massive bombings that followed were at once a prelude and a sidebar to the Vietnam War. The original idea was to recruit the Hmong tribespeople of the Laotian highlands to fight the communist Pathet Lao and their allies, the North Vietnamese. Unlike the later American invasion of Cambodia, another sub-war of the larger conflict, it was conducted in the dark so far as the media were concerned and even today, 50 or 60 years later, continues to fascinate and horrify.

Kurlantzick focuses on four characters. There is William Sullivan, the U.S. ambassador to Laos in the early 1960s, who worked hard to turn a minor war into a major one; William Lair, a lone-wolf anti-bureaucratic field operative who ran the war show on the ground and in the air; and Tony Poe, an alcoholic misfit who by 1965 had had 20 years’ experience in firefights, “had never held a job that did not involve fighting” and — nice understatement — “found himself ill-suited for civilian life.” (Poe collected the severed ears of his enemies as trophies of war — bags full of them.) The fourth figure, Vang Pao, was the charismatic and paranoid military leader of the Hmong who exploited the Americans and was exploited by them in turn as he repeatedly led his bizarre ragtag army into battle.

The story began in the 1950s. President Dwight Eisenhower, though hardly a proponent of European colonialism, supported the French in their losing fight to keep Indochina because he feared the Pathet Lao and other communist groups were angling for control throughout Southeast Asia, which the Americans saw as a palisade of wobbly dominoes. Such anxiety led him to place enormous emphasis on the strategic importance of the little landlocked monarchy of Laos, one of the world’s poorest nations, where the average income was $75 US a year. Amazingly, the joint chiefs of staff and the Eisenhower cabinet “even discussed launching tactical nuclear weapons if the political situation in Laos continued to deteriorate.”

In his last days in office, early in 1961, Eisenhower approved the CIA’s plan to arm and train the Hmong in the northern part of the country. His successor, John F. Kennedy, continued such support for the rest of his short life, but on nothing like a scale later endorsed by Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. In the Eisenhower and Kennedy days, the people who plan wars were fairly certain that one was required in Laos even more than in, say, neighbouring Vietnam. Later, the two conflicts merged.

The h is silent

The Hmong are found throughout Southeast Asia as far west as Myanmar. There are three million of them in China and perhaps half a million in Vietnam. They all share a common language, but are separated from one another in other ways, both cultural and political. Many Vietnamese Hmong sided with the communists, in contrast to most of those in Laos, who are subsistence farmers and hill people who prefer elevations above 800 metres and distrust the lowland Laotian majority — and almost everyone else. The CIA started off small, selecting a thousand Hmong men to train and equip with obsolete small arms, paying them through a third party. Vang Pao, who had fought the Japanese and the French, would now become a leading anti-communist proxy of the Americans, battling both the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese.

By 1970, Vang’s army had grown to 30,000. In the course of the 1960s, the number of military and civilian contractors hired by the CIA (mercenaries, most of them) had increased by 2,000 per cent. Now it is estimated that in the same period, the agency annually spent what today would be $3.1 billion US on the failed campaign. Kurlantzick calls the effort “a transformational experience [given that until then] the CIA had never mounted a significant paramilitary operation” on such a scale and in such secrecy. “In fact, no spy agency anywhere in the world had [done so]. The Laos war would prove the dividing line for the CIA; afterward, its leadership would see paramilitary operations as an essential part of the agency’s mission, and many other U.S. policy-makers would come to accept that the CIA was as much a part of waging war as the traditional branches of the armed forces.” For people such as those Kurlantzick profiles at length, the system had the key advantages of tight secrecy, loose oversight and almost unlimited funding.

Vang, who may or may not have been an important figure in the heroin trade as well, had his base at Long Cheng in the north, close to both the eastern and western borders. One might almost say it became a kind of boom town. The Americans were constantly urging the Hmong to engage in big battles and act less like guerrillas. Such tactics resulted in massacres of Hmong soldiers and civilians alike. The most hideous battle was in 1968 at a place named Nam Bac. Vang had repeated the mistake that the French forces had made when they were overrun by the Vietnamese communists at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. He fortified a low-lying plain surrounded by mountains, which allowed the enemy to repeatedly destroy the airstrip that was the only means of getting in and out. The defenders exhausted their supplies and were killed or captured.

The most striking feature of the secret war (that is, other than its secrecy) was the American bombing campaign on the portion of Laos through which ran the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the route used by the North Vietnamese to supply their forces fighting in the south.

The trail cut through the Plain of Jars, an area of northern Laos in Xieng Khouang province, dotted with ancient sandstone burial urns dating back as far as 2,500 years: the work of a civilization now lost to us. This famous “mortuary landscape,” a world-class archeological site spread across an area of 1,300 square kilometres, was subjected to American carpet bombing: hundreds of sorties daily, day after day, adding up to 580,000 flights over 10 years and the dropping of 1,800 kilograms of ordnance for each man, woman and child. B-52s let loose 113-kilogram and 226-kilogram bombs (the sizes ran up to 1,360 kilograms); one aircraft could drop 907,000 kilograms worth in a night without ever being seen, following up with napalm and chemicals designed to destroy vegetation and put an end to agriculture. Cluster bombs were the ones most feared by the Hmong, who returned to their homelands once the North Vietnamese were gone. These devices were full of ”bomblets.” One B-52 Stratofortress could saturate 2.6 square kilometres with 7.5 million steel pellets. Some contend that the amount of explosives dropped on this region — based on mere tonnage, rather than results — far surpassed the total dropped on Dresden and other German cities in the Second World War.

The final chapter

I’ve been to the Plain of Jars. It is a spooky place, a high plateau, somewhat flinty and with the reddish mud that always seems to recur in Vietnam War memoirs. In the distance are sharp-sided mountains all around. One has to hire a local guide and very carefully follow in his footsteps — literally, for he knows where the baseball-sized explosives are likely to be found. Hmong hunters sometimes pry open the explosives in search of gunpowder to use for hunting (though a few men still carry crossbows). High up in the hills and certainly in Phonsavan, the only real town nearby, one sees many amputees, young as well as old.

The end of the story is suitably bizarre. The Americans, dutifully, felt an obligation to let many of the Hmong, those who worked for them against the communists, come to the United States after the war. These new immigrants included the wily old warrior Vang Pao. His resettlement was not without incident, for he was arrested for using the U.S. as a place from which to plot a coup against the Pathet Lao (who are still in charge). The majority of the American Hmong congregated in two spots — Fresno, California, and Minneapolis-St Paul, Minnesota. The latter’s climate must have taken some getting used to. Vang lived in both places at various times. He died in 2011.

I’ve been expecting you, Mister Bond

I’ve been expecting you, Mister Bond

No one would write a book attempting to explain the whole of Canada by focusing solely on the city of Ottawa. Certainly no one would concentrate exclusively on the city of Canberra to define Australia. The same rule applies to Turkey. Ankara is the hub of government, but Istanbul has always been the centre of politics, religion, culture, trade — and trouble. The Emperor Constantine named it in his own honour in 330 AD, and during its long run as Constantinople, it was invaded every so often by Arabs, Russians, Crusaders and others — in, for example, the years 717, 813, 860, 913, 924, 941, 1203, 1261, 1394, 1402 and 1453. The last of these was the most important, for it made the city the capital of the Ottoman Empire, ruled by an endless succession of despots, sultans, generals and the like.

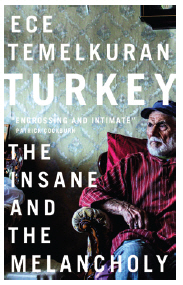

In the present republican era, which dates back to 1923–24, Turkey has had as many coups and attempted coups as Thailand. The most recent failed takeover, last year, has resulted in fierce retaliation and repression by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AKP, or Justice and Development Party. Policies in place now mean that “the Kurds could not speak Kurdish, the left could not speak of ideology, women could not fight for their rights, workers could not resist, and much more.” So writes Ece Temelkuran, a prominent Turkish novelist and (until she was recently fired from her newspaper) journalist, in her new book, Turkey: The Insane and the Melancholy (Zed Books, $25 paper). It’s no wonder that many new titles about Turkey are appearing at the moment, given the country’s accelerated turn away from the West amid general fears of even worse authoritarianism. Some western writers follow the almost traditional route and use Istanbul to examine the entire state and its culture. Recent examples are Istanbul: Tales of Three Cities by Bettany Hughes (Hachette Canada, $24) and Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads by Thomas Madden (PenguinRandom Canada, $30). Others are understandably more polemical — for example, Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey by the novelist Kaya Genç (I.B. Tauris, $30). But Temelkuran’s work stands alone for being, well, unusual.

She is one of those courageous reporters, exemplified by Mohamed Fahmy from Egypt, who accept great risks in writing about the atrocities they have seen at first hand — have, in fact, lived through. Temelkuran is certainly one of these who rises up to speak freely, but her book, at least in this translation from the Turkish, stands out for being eccentric, angry, gossipy, off-the-cuff, more talkative than expository, and just generally cobbled together, though, of course, this is not to deny the importance of its message.

Another of the new breed of brave and even death-defying journalists is Mikhail Zygar, who was the editor-in-chief of Russia’s only privately owned television network, but who (again, like Temelkuran) was forced out of his position. The reason for his departure was the popularity, not to say the mere existence, of his book, All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin, which has now been translated into English (Hachette Canada, $36.50).

During the Cold War (perhaps we should now call it Cold War One) many American foreign policy soothsayers in government, in think-tanks and in universities were referred to as Kremlinologists. These days, a far more precise term is cropping up: Putinologists. In the 17th-Century, Louis XIV, the Sun King, famously said, “L’état, c’est moi.” Many western outsiders, as well as dissidents and other disillusioned people inside the country, can imagine Putin making the same statement in Russian. But Zygar goes beyond that image and emerges with a surprising conclusion.

Putin is certainly in the strongman tradition of autocratic governance, but, in Zygar’s analysis, not nearly so powerful as we routinely imagine. Rather, he is a “hurt and introverted outcast” who must keep lining the pockets of a selected few (as well as his own) and could not retain power without not only the oligarchs he creates, but also the senior bureaucracy all around him and the regional governors. Plucked from relative obscurity by Boris Yeltsin, he actively tolerated the West (but didn’t engage it the way Dmitry Medvedev — his chosen successor, but actually just his political placeholder — did before the two men turned on each other). At the moment, he’s throwing every irritant he has at the West — Edward Snowden, the U.S. hacking allegations, and, of course, his reckless and brutal adventurism in Ukraine, Crimea and Syria. Although such events first raised his standing domestically, they, and other factors, now are having the opposite effect. Many Russians hate the corruption of Putin’s regime, but he responds to their challenges with more arrests and imprisonment.

Putin is certainly in the strongman tradition of autocratic governance, but, in Zygar’s analysis, not nearly so powerful as we routinely imagine. Rather, he is a “hurt and introverted outcast” who must keep lining the pockets of a selected few (as well as his own) and could not retain power without not only the oligarchs he creates, but also the senior bureaucracy all around him and the regional governors. Plucked from relative obscurity by Boris Yeltsin, he actively tolerated the West (but didn’t engage it the way Dmitry Medvedev — his chosen successor, but actually just his political placeholder — did before the two men turned on each other). At the moment, he’s throwing every irritant he has at the West — Edward Snowden, the U.S. hacking allegations, and, of course, his reckless and brutal adventurism in Ukraine, Crimea and Syria. Although such events first raised his standing domestically, they, and other factors, now are having the opposite effect. Many Russians hate the corruption of Putin’s regime, but he responds to their challenges with more arrests and imprisonment.

Yet apparently not enough to silence the ominous grumbling brought on by the U.S.’s economic sanctions and other aspects of economic decline leading to what we’re told is a steady current of widespread (and possibly mass) unrest.

Zygar has apparently done what no one else has done. He’s interviewed a hundred of the people closest to Putin.

And finally…

Bob Shacochis is a much-praised American political novelist, known especially for The Woman Who Lost Her Soul. But he began his career as the highest kind of literary travel writer — a long-form travel essayist and master of non-fiction prose. He has now collected the cream of his past work in that field as Kingdoms in the Air: Dispatches from the Far Away (Publishers Group West, $38.50). He girdles the globe, as people used to say, and the most ambitious and evocative piece deals with Nepal. Another takes the reader to Mount Ararat in Turkey. It invites a fascinating comparison to a new Canadian book on the same topic: Full Moon over Noah’s Ark: An Odyssey to Mount Ararat and Beyond by prominent Vancouver travel author Rick Antonson (Skyhorse $24.99).

George Fetherling is a novelist and cultural commentator. His novel The Carpenter from Montreal will appear this autumn.