A version of this speech was delivered as the keynote address at the Canadian Committee for World Press Freedom luncheon in Ottawa on May 2.

It was 1903 and Pennsylvania governor Samuel Pennypacker had had enough. After a year of being depicted as a parrot by the cartoonist Charles Nelan of the North American, [a daily newspaper in Philadelphia], the governor wanted the satirical drawings stopped. The reason for Pennypacker’s frustration was that the cartoonist was using this visual metaphor to portray him as a mouthpiece for special interests. The governor did not take kindly to that and had an anti-cartoon bill introduced into the state legislature in order to silence his detractor. The bill proposed a ban on “any cartoon or caricature or picture portraying, describing or representing any person, either by distortion, innuendo or otherwise, in the form or likeness of beast, bird, fish, insect, or other [non-]human animal, thereby tending to expose such a person to public hatred, contempt or ridicule.” Pennypacker’s attempt to silence his critic backfired, though, when another cartoonist proceeded to draw the governor as a tree, a beer mug and a turnip.

A more contemporary example happened just a few months ago. Newly elected President Donald Trump invited a group of cable news anchors and executives to Trump Tower, ostensibly to open up a dialogue between the administration and the media, whose relationship at this point had become contentious. Instead, it was reported that Trump spent most of the time complaining about how he was being treated in the press and even brought up how displeased he was with one news organization that kept using a photograph which prominently showed his double chins. My colleague Signe Wilkinson of the Philadelphia Daily News wasted no time sketching and tweeting a drawing showing Trump with about 10 chins.

All cartoonists have used mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, inanimate objects, you name it, because visual metaphors are part of our language. It is the editorial cartoonist’s job — through satire and ridicule, humour and pointed caricatures — to criticize badly behaving leaders and governments. It is our purpose to hold politicians and powerful institutions accountable to the people they are supposed to serve.

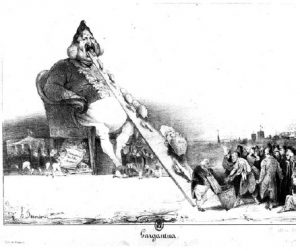

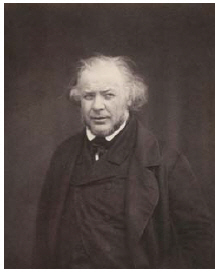

Cartoonists have been targeted throughout history by humourless politicians and heads of state. From Honoré Daumier being imprisoned for drawing the French king as Gargantua (he also drew him as a pear) to Ali Ferzat’s hands being broken over his critical cartoons of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, cartoonists are jailed and physically attacked because, through their satire, they threaten those who are abusing their power. Even in countries with traditions of free expression, as we’ve experienced in Denmark and France, cartoonists have been threatened and killed by Islamic fundamentalists who decide that violence is a justified response to perceived offences to their religious beliefs.

Why do cartoons cause such a visceral response? Because cartoons are universal, every human being responds to these seemingly simple drawings. They transcend language and class. Everyone, from the highly educated to the illiterate, can relate and see themselves in cartoons. Editorial cartoons can be subtle, cutting and usually humourous, but they also can be visually disturbing, depending on the subject matter. And if an editorial cartoon is good, it has a strong point of view that makes the reader think and challenges preconceived notions.

A recent example of cartoonists being targeted for their work is Atena Farghadani from Iran. She was first arrested in August 2014 for a critical cartoon depicting a group of Iranian lawmakers as various animals. This drawing was her response to an anti-contraception bill in the parliament that would have set Iranian women’s reproductive health back decades. During her imprisonment, Farghadani was beaten and interrogated for nine hours at a time and was also forced to undergo a “virginity and pregnancy test” because she had been seen shaking hands with her lawyer. These tests are in reality sexual abuse — and are employed specifically against women to intimidate and silence them, as they were used in Egypt during the Arab Spring. After Farghadani was released, she posted a YouTube video documenting her treatment and was again arrested in January 2015. She was given a prison sentence of 12 years and nine months for insulting the supreme leader, the Iranian president and members of parliament, among other charges. After a worldwide effort by cartooning and human rights organizations, she was finally released in May 2016.

The cartoonist Zunar has been harassed and arrested several times during the last few years for his critical cartoons calling out the corruption of the Malaysian government. His offices have been raided, his artwork and books confiscated and his exhibitions attacked by government supporters. Zunar has been banned from travelling outside of Malaysia and is currently fighting numerous sedition charges and facing a possible 43 years in prison.

Five months ago, journalists from the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet, including its cartoonist, Musa Kart, were detained as part of an overall crackdown on dissent by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Kart has been a vocal critic of government corruption and targeted Erdogan, first as prime minister and then as president, for many years in his cartoons. The Turkish president has a history of not tolerating criticism and ridicule, once arresting a 16-year-old who Erdogan said had insulted him after the boy blogged about government corruption. Another time, Erdogan requested that German Chancellor Angela Merkel prosecute a comedian who ridiculed him in a satirical televised sketch. Kart is still in jail today and charged with “helping an armed terrorist organization.” His trial date has been set for July 24.

Another Iranian cartoonist is being held by the Australian government in a refugee detention camp at Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. He goes by the name “Eaten Fish” and has been held for three and a half years, suffering from mental illness and sexual abuse while detained in terrible conditions on the island facility. Even in this horrible situation, the young Iranian cartoonist is creating drawings illustrating the human rights abuses he and his fellow detainees are enduring. Cartoonists from around the world — especially Australian cartoonists — continue drawing cartoons criticizing the actions of their government and supporting Eaten Fish.

I used to tell my colleagues from around the world that American cartoonists never had to worry about being imprisoned for our cartoons because we have the First Amendment as our protection. But I’m not so sure anymore. We haven’t experienced Trump’s Republican-controlled Congress introducing any bills that ban caricatures of him as a bird, fish or vegetable, but Trump has more than once complained about the press attacking him and how unfair his coverage has been. Trump is as thin-skinned as Erdogan when it comes to being made fun of, as we’ve seen in his Twitter feed after Saturday Night Live. He has tweeted that the “FAKE NEWS media … is the enemy of the American people” — and of course his definition of “fake news” means anyone criticizing him or not portraying him in a favourable light. That’s a significant choice of words and dangerous to the role of a free press in a democracy. White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus said in a recent interview that libel laws are “something that we’ve looked at.” I find it very unsettling that a president of the United States doesn’t seem to understand the First Amendment and thinks the role of a free press is the same as his personal PR firm.

February will be the 30th anniversary of the Supreme Court of the United States’ decision in the Hustler v. Falwell case. The case was about a parody advertisement in Hustler magazine that targeted Jerry Falwell, a politically active Christian fundamentalist minister during the 1980s and ’90s. It was a pivotal case for American editorial cartoonists because it dealt with the First Amendment’s speech protection and whether it extends to satire when it includes offensive statements about public figures resulting in, as Falwell’s attorney described it, “emotional distress.” This case, although not specifically about cartoons, had ramifications for editorial cartoonists since we use satire and caricature in our political commentary. The court ruled unanimously that the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech bars allowing public figures to recover damages against those who comment on their actions. As then-chief justice William H. Rehnquist wrote in the opinion of the court, “Were we to hold otherwise, there can be little doubt that political cartoonists and satirists would be subjected to damages awards without any showing that their work falsely defamed its subject.” He went on to write, “Despite their sometimes caustic nature, from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate.”

I’ve always felt in the United States that an editorial cartoonist is the bastard child of journalism. This is because most editors see us only as comic relief, less than the serious, legitimate opinion writer. In reality, the only difference is that we use images and satire to express a point of view. And specifically because of the visual language we use, cartoonists will always be first in the line of fire when controversial subjects are being debated and free speech is threatened. Editorial cartoonists are a barometer for all of our free-speech rights; a silenced cartoonist is an indicator of an unhealthy environment for freedom of expression in any society. If we want to protect free speech and the free press, we must vigourously protect the editorial cartoonist.

Ann Telnaes in a cartoonist syndicated with Cartoonists and Writers Syndicate/New York Times Syndicate. She was the winner of the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 2001.