Canada is celebrating its 150th birthday this year and on the other side of the world perhaps the most profound such observance right now is the centenary of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Several important new books on the subject are being published. All of them struggle, some more successfully than others, to explain the incredibly complex web of events that made Russia view the west as its enemy and vice versa.

S.A. Smith of Oxford University is certainly one of the most important historians in the crowded field of Russian studies. He holds the unusual distinction — unusual for someone in the west at least — of having been educated at universities in Moscow and Beijing. He has published noted books on each of these countries’ communist revolutions, not to mention a work comparing the two. Some years ago, he wrote an excellent beginners’ guide to the Russian uprisings in the wonderful Oxford University Press series called Very Short Introductions. His new title, Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis, 1890‑1928 (Oxford, $34.95), is like a vast enlargement of the small one, taking into account a great deal of fresh research and thought.

The two dates he uses as bookends in his title are somewhat elastic. Yes, they encompass the period when the Russian Empire fell and the Soviet Union sprang up in its place, but why those two dates in particular? Well, 1890 was probably the apex of czarist economic expansion, industrialization and infrastructure-building (as seen by the fact that the Trans-Siberian Railway was just being built). The year 1928 is more firmly fixed in history. By then, Stalin was already in charge and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had begun collectivization and the first five-year plan was under way.

In a nutshell, what caused the Russian Revolution? Despite the way it was governed, the Russian Empire and its aristocracy in particular were no less sophisticated than the British or the French ones, but were, to say the least, much more resistant to change. Until Russia’s status quo began to crumble, for example, the country still followed the Julian calendar, which lagged behind the Gregorian calendar that other western countries had been using for generations. The Russians were thus 12 days behind everyone else (later, 13): a small but telling point. And, again as compared to the other European imperial powers, Russian society was far more cruel.

The time of troubles redux

Tyrannical czars and emperors, including nonetheless remarkable ones such as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great, enforced a culture of terror that dragged on for century after century. The last Russian dynasty, the Romanovs, of which these two Greats were part, had begun on a promising note with the first Michael bringing an end to what is called the Time of Troubles. But, of course, new and different troubles began to replace the old ones. In Simon Sebag Montefiore’s ironic and euphemistic observation, Russian leaders went along ruling as they always had done, with an “effulgent majesty” that they attributed to God. This delightful phrase is found amid the horrors described in his book, The Romanovs: 1613-1918 (Knopf Canada, $37.50). The rumbling of the masses grew louder and louder. In 1887, Alexander Ulyanov was executed for plotting to assassinate Czar Alexander III. In 1895, Ulyanov’s younger brother, who took the name V.I. Lenin, was sentenced to 13 months in solitary and three years in Siberia.

In 1896, when Lenin was still incarcerated, Nicholas II was crowned, unaware, of course, that he would be the country’s last czar (yet suspecting that he might be the last Romanov one, because his only son was a hemophiliac). For a while, certain events — sometimes important ones — hinted that conditions might be improving. But we can see now that once the tipping point was reached and events began to get out of hand, the decline into chaos was inevitable.

Russians at this time were quite expansionist with respect to the farthest reaches of the empire in the east (consider the Trans-Siberian Railway once again). They controlled Vladivostok, but needed another seaport, one that could operate year round. In 1904, they provoked a war with Japan, hoping to establish a port on the Korean Peninsula (which Japan had recently captured). All the smart money was on Russia, but such bets were folly. Japan opened with a sneak attack on the Russian squadron at Port Arthur. They then carried on into 1905, decimating not only Russia’s navy, but also the czar’s troops on land.

Russians at this time were quite expansionist with respect to the farthest reaches of the empire in the east (consider the Trans-Siberian Railway once again). They controlled Vladivostok, but needed another seaport, one that could operate year round. In 1904, they provoked a war with Japan, hoping to establish a port on the Korean Peninsula (which Japan had recently captured). All the smart money was on Russia, but such bets were folly. Japan opened with a sneak attack on the Russian squadron at Port Arthur. They then carried on into 1905, decimating not only Russia’s navy, but also the czar’s troops on land.

As Nicholas was losing the war, he was losing his authority as well. To bolster his position, he called a conference of regional governors and promised to institute various social reforms. But the changes were never enacted. People were becoming increasingly radicalized. From his exile in Switzerland, Lenin awaited his opportunity to pounce. Before he could do so, however, a mob of angry workers marched on the czar’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. In what became known as Bloody Sunday, Nicholas’s forces massacred hundreds of them, setting off riots and work stoppages nationwide.

In sympathy, the starving crew of the battleship Potemkin, part of the Black Sea fleet, mutinied. Nicholas responded to such disturbances with a promise of civil liberties and a new legislative structure, to be reinforced by a constitution called the Fundamental Laws. In that way, he took the air out of the attempted revolution of 1905, but he wouldn’t survive the vastly bigger one to come.

And briefly…

Will U.S. President Donald Trump actually build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico (or rather extend the sections constructed during the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, and join the new and old bits together to make a single continuous barrier)? He keeps saying he will, but the picture of it in his mind seems to change shape. As of this writing, his latest idea is to construct the barrier out of giant solar panels so as to pay for the construction by selling the energy the project would generate.

Will U.S. President Donald Trump actually build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico (or rather extend the sections constructed during the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, and join the new and old bits together to make a single continuous barrier)? He keeps saying he will, but the picture of it in his mind seems to change shape. As of this writing, his latest idea is to construct the barrier out of giant solar panels so as to pay for the construction by selling the energy the project would generate.

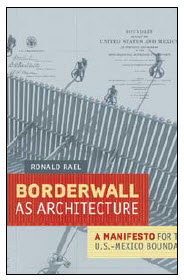

At least some apparent experts have pronounced this scheme unworkable. Then there’s Ronald Rael, a professor of architecture at the University of California at Berkeley who briefly takes the idea seriously in his highly unusual book, Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (University of California Press, $29.95 paper). This is a work that harks back to the days of Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan — especially the latter. Rael tosses out ideas on nearly every page, seemingly for the fun of doing so.

Here are some of his notions: a wall made of mesh so that an American horse and a Mexican one can race each other along its path, or a wall that becomes invisible when the air above is heated to the point at which one sees not the real wall, but merely a mirage. Other thoughts include teeter-totters so that a child in Mexico can see-saw with an American kid on the other side of the divide. But Rael has a serious message as well. He thinks the idea of a wall is farcical and would not limit illegal immigration.

A sober discussion of various present-day border walls can be found in Marcello Di Cintio’s relatively recent book, Walls: Travels Along the Barricades (Goose Lane, $29.95). In the end, I suppose, the sorts of walls discussed in such books either work or fail according to their intentions. The Great Wall of China was built to bar invaders from the north. But China was overrun anyway. By comparison, Hadrian’s Wall, built across the narrowest part of Great Britain in the 1st Century BCE, wasn’t so much an obstacle to kept people out as it was a means of regulating the flow.

An author himself, George Fetherling’s new novel is The Carpenter from Montreal.