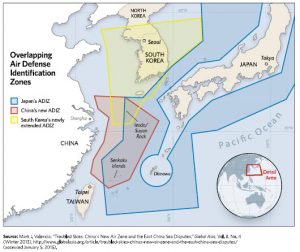

In December 2015, China and South Korea established a telephone hotline between their national defence ministries. Mainland China and South Korea share a maritime border in the Yellow Sea as well as bordering Air Defence Identification Zones. While there are some maritime and fisheries issues between them, the two countries enjoy generally peaceful relations. According to the South Korean defence ministry, it expects to “proactively capitalize on the hotline to improve mutual understanding and trust and to reinforce high strategic communications.”

Yet, in January 2017, when China dispatched a training flight of 10 Xian H-6 strategic bombers that flew through the South Korean-designated Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ), the South Korean military reportedly found that the bilateral hotline was not initially functioning. There was a subsequent response on the Chinese end of the hotline more than 15 minutes later — a long period of flying time for a jet bomber formation.

While no reason for the slow response was given by the Chinese side, the incident points out the limitation of depending on hotlines for confidence-building. If one side does not pick up the confidential phone call or answer the secure fax, there is unlikely to be inter-state trust.

More recently, confidential bilateral hotline discussions took place over several months after Chinese complaints about the U.S.-supplied THAAD missile shield system being deployed in South Korea in the face of further North Korean missile tests. Chung Eui-yong, the head of the National Security Office at South Korea’s presidential office and Yang Jiechi, senior diplomat and councillor for foreign affairs in the State Council in Beijing, reportedly narrowed their differences gradually to enable the two sides to issue a joint statement of understanding on national sovereignty.

North Korea also borders the Yellow Sea and regularly disputes the West Sea Maritime Boundary between its waters and those of South Korea. In fact, there have been hostile engagements between the North and the South in the area. In March 2010, South Korea’s ROKS Cheonan corvette was torpedoed under disputed circumstances. South Korea claimed that it had been sunk by a North Korean midget submarine, while the North denied the charge. Then, in November the same year, the North Korean People’s Army launched an artillery bombardment of the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong near the maritime border. Currently, even with increased North Korean nuclear tests and ballistic missile launches, the North-South hotlines on the Korean Peninsula are not working, having been disconnected by North Korean authorities since February 2016.

Confidence building in East Asia

What are known in the media as “hotlines” or communications mechanisms, are called Direct Communications Links (DCLs) by foreign governments. Usually encrypted, these diplomatic or military hotlines permit high-level direct communications between different national authorities at times of tension or crisis. They are supposed to be a confidence-building measure for tension reduction. While states often maintain diplomatic presences, the ability to directly address national authorities and senior decision-makers can head off crisis situations.

In recent years, more hotlines have been established in the East Asian region, with others under discussion. Currently, the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump is reviewing its policy with Asia and is moving away from former president Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia. In this emerging situation, with Trump’s unpredictability being a key factor, such high-level hotlines may prove essential to containing and dampening down rising tensions and emerging crises in East Asia.

At the June 2017 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, the Asian region’s premier security forum, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in his keynote address that “we [as neighbouring countries] have to take responsibility for our own security and prosperity, while recognizing we are stronger when sharing the burden of collective leadership with trusted partners and friends.” Within this regional perspective, more countries, especially China, are creating diplomatic and military hotlines to encourage trust, and to reduce political and security tensions.

According to a January 2017 white paper on China’s policies on Asia-Pacific security co-operation, the Beijing government is seeking a more expansive security role in the region. The paper states that “China will shoulder greater responsibilities for regional and global security and provide more public security services to the Asia-Pacific region and the world at large.”

This language is similar to the declared role of the United States in supporting regional and international security and stability — at least until the end of Trump’s presidency.

In an August 2017 speech marking the 90th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, Chinese President Xi Jinping issued a tough line on national sovereignty. Faced with a number of territorial disputes with his country’s neighbours — over the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the island of Taiwan and the borderlines in the Himalayas — he declared China would never permit the loss of “any piece” of its land to outsiders and added that “no one should expect us to swallow the bitter fruit of damage to our sovereignty, security and development interests.”

A China-Japan hotline

Mainland China currently has disputed claims over a group of small islets — referred to as the Diaoyutai Islands by China and the Senkaku Islands by Japan and controlled by Japan — in the East China Sea. While the islets are uninhabited, they do enable Japan’s access to an exclusive economic zone for valuable fisheries and potential sub-ocean gas and oil deposits. Surprisingly, while China and Japan have reached a working accord on the joint development of the sub-ocean deposits, China antagonizes Japan with continuous tension-producing naval operations and aerial flights near and over these islets.

China has regularly dispatched People’s Liberation Army aircraft formations to fly through the international air strip over the Miyako Strait between the Japanese southwestern islands of Okinawa and Miyako to conduct training operations across the “First Island Chain” defence line of islands in the Western Pacific. China has also flown operations around the island of Taiwan, though outside its ADIZ, and passing through the Bashi Channel, which lies between southern Taiwan and the Philippines. All of these training flights necessitate an aerial interception response by the Japanese or Taiwanese air forces respectively.

Over the past five years, Chinese and Japanese officials have held on-again-off-again consultations on maritime affairs between their two countries. The main focus of these discussions is the implementation of a “maritime and aerial communication mechanism,” namely a hotline between their senior defence officials to prevent possible accidental clashes in the East China Sea where Chinese forces are testing the sovereignty of three small Japanese-controlled uninhabited islets. Though the two countries have yet to agree on an operational defence hotline, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper reported in early December that “an agreeement in principle” at been reached.

China-Taiwan hotline unused

In December 2015, China’s government, under Xi, and then-Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou established an operational, encrypted telephone hotline between the two countries as a tension-reducing measure across the Taiwan Strait. This direct hotline connected China’s Taiwan Affairs Office with Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council — both state cabinet-level ministers — though previously there were existing “hotlines” connecting cross-strait agencies’ deputy directors and the semi-official organizations that negotiated cross-strait agreements due to the absence of formal relations.

During Ma’s term of office, Taipei and Beijing signed 23 agreements to promote smoother commercial, civil, criminal and transport relations across the strait. But cross-strait ties have cooled since President Tsai Ing-wen took office in May 2016, mainly due to her refusal to heed China’s demands to accept the “1992 consensus” as the sole political foundation for political and societal interactions between Taiwan and China. The “1992 consensus” refers to a tacit understanding reached between the mainland Communist government and Taiwan, under the then-Kuomintang government, that there is only one China with both sides free to interpret what that means.

Since Tsai assumed office in May, meetings between mid-level mainland and Taiwanese government officials have been repeatedly delayed or cancelled — and the much-publicized ministerial hotline has gone “dead,” with the Chinese Communist side not answering.

While lower-level commercial, health and policing officials still meet to discuss priority issues and exchange necessary information, high-ranking Taiwanese officials are restricted by the Chinese government from attending meetings on the mainland. There are work-around opportunities through which discussions could be held on the sidelines of international gatherings, when Chinese officials have permitted such interactions. Nevertheless, it is still possible for a senior Taiwanese official to pickup the confidential telephone or use the secure fax to contact his or her counterpart across the Taiwan Strait. Where the problem arises is if the counterpart chooses not to answer the call.

A China-Philippines hotline

In January 2013, the Philippines began formal arbitration proceedings against China’s “nine dash” line claim regarding the Spratly Islands, also known as the Nansha Islands, in the South China Sea. In its July 2016 ruling, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague decided that China’s “nine dash” line map was not historical proof of sovereignty and that its claim on South China Sea islands did not give China sovereign authority and therefore no claim to a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). But the Chinese government has refused to recognize the tribunal’s authority under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea or its 2016 ruling.

Nevertheless, since taking office in June 2016, current Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has sought to mend relations with China — as, according to his foreign minister Alan Peter Cayetano, “no mechanism exists to legally enforce any deal” under the tribunal’s judgment.

The Chinese government, for its part, prefers quiet diplomacy — as long as it does not lose face in the region — and has negotiated a number of sizable economic investment deals with the Philippines.

In addition, Filipino fishermen have been allowed back onto their traditional fishing grounds, where earlier they had been harassed by larger Chinese coast guard vessels. And, in February 2017, a hotline mechanism between the Philippine coast guard and the Chinese coast guard was established to provide a direct communication link and “point of contact” on enforcement issues and unlawful acts at sea. It has greatly assisted “open sea” working relations.

China-ASEAN hotlines

The South China Sea is one of the primary international maritime routes as the main waterway between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. An estimated $5 trillion US in trade moves through this waterway each year. In addition, the waters are a major fishing ground and food source for the coastal countries, as well as a prime area for drilling for oil and gas reserves.

But the sovereignty over the islands, reefs and shoals in the South China Sea — particularly the Spratly archipelago and the Paracels archipelago — are disputed by China and various Southeast Asian nations, including Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. Notwithstanding the tribunal judgment against its ownership of the majority of the South China Sea, China has conducted expansive land reclamation by dredging sand up from the sea bottom onto seven of these islands or islets, enlarging their area, creating new harbours, installing military facilities including airstrips, anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile sites and other support units.

In September 2016, China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed to establish a hotline mechanism to contact the ministries of foreign affairs of China and the 10 ASEAN countries. It was tested in March of this year and it was deemed successfully operational to defuse tensions between these countries in the South China Sea.

And in October 2017, the ASEAN countries launched the ASEAN direct communications infrastructure — a direct hotline between the defence ministers of all the ASEAN countries. These top-level ministerial hotlines could prove essential for security and stability in the region, as the Southeast Asian countries appear to be moving into a balancing position between the orbits of Trump’s United States and Xi’s China in 2018.

Hotlines and Asian security into 2018

Over the past few years, the number of top-level confidential hotlines has increased, with a goal of dealing with inter-state issues and defusing possible emerging crises in East Asia. And it seems likely there will be even greater reliance placed upon such communications to boost confidence in the Trump era.

Despite his November state visit to five Asian countries, including Japan, South Korea, China, Vietnam and the Philippines, Trump’s ongoing “combative rhetoric” continues to alarm many American allies in the region — and possibly even China and North Korea, as well. This worrying view could encourage greater use of regional hotlines in the Asian region.

At the same time, it could strengthen security interlinks and exercises and trade relations with an expansive China. It is expected that the Chinese Communist government in Beijing will continue to project outward sovereignty assertiveness. This will be justified as being designed to protect against self-declared threats to its national “core interests” in the East China Sea, the South China Sea as well as in the Western Pacific in general and the Indian Ocean.

Nevertheless, China’s inclusion — perhaps even at the centre of the growing regional hotline web — can help ensure that regional air and naval security can be maintained, and could even prevent potential armed confrontations.

Before retiring, Robert D’A. Henderson taught international relations at several universities. He currently does international assessments and international elections monitoring.