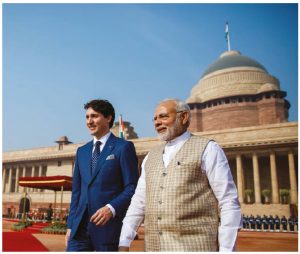

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s much-discussed state visit to India in February was seen as an opportunity for a major reset on bilateral relations with the world’s largest democracy. However, things did not go as planned.

Canada isn’t alone in its desire to improve relations with the massive country. India, with a GDP of more than $2 trillion US, is a coveted trading partner. The International Monetary Fund projects its GDP will grow by 7.4 per cent this year, making it a high-priority trading partner for many governments.

These negotiations are not new — talks on the Canada-India Foreign Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement (FIPA) date back to 2004 and the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) discussions began in 2010. In September of that year, a Canada-India joint study, titled Exploring the Feasibility of a Comprehensive Economic Partnership, forecast GDP gains of between $6 billion and $15 billion US for Canada. The CEPA agreement was expected to be completed by 2013, but instead, on the heels of what was supposed to be a relationship-mending visit, both agreements linger unsigned.

Two-way trade is not currently insignificant, but it could be much greater. Trade in goods totalled $8.3 billion in 2017, with trade in services at $2.1 billion and a still-optimistic Kasi Rao, president of the Canada-India Business Council (C-IBC), says “the modesty of the numbers reflects the past, not the promise of the future.”

Canada isn’t the only player undergoing a long negotiation process with India. Australia, New Zealand and the EU have all initiated trade talks, but none has yet concluded a treaty.

David Mulroney, a retired Canadian diplomat, recently wrote a piece in The Globe and Mail talking about Canada’s and India’s differences.

“India,” he wrote, “takes a prickly approach to global issues that is often at odds with traditional Canadian policies … While they might ultimately agree to grant Canada a concession, [it would be] a product of hard and often heated negotiations. They [would] never concede a point because they like us or because we are home to a large Indo-Canadian community.”

The February talks focused on trade, defence, civil nuclear co-operation, space, climate change and education. As well, the national security agencies of both countries decided to establish a “framework for co-operation on countering terrorism and violent extremism.”

The countries signed three memorandums of understanding, namely for co-operation in the fields of science, technology and innovation, in higher education and on intellectual property rights.

They also exchanged terms of reference to step up co-operation on energy issues and signed a joint declaration of intent in the field of information and communications technology and electronics as well as an agreement on co-operation in sports.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi later acknowledged that “India has attached a high importance to pursuing its strategic partnership with Canada. Our ties are based on democracy, pluralism, the supremacy of law and mutual interaction.”

However, actions can sometimes speak louder than words. Last November, the Canadian pulse industry was blindsided when the Indian government put a 50-per-cent import tariff on dried peas. In December, India then imposed a 30-per-cent tariff on lentil and chickpea imports — the latter later being raised to 40 per cent. These actions have seriously hurt Canadian pulse producers by virtually eliminating India as an export market.

No mention was made about the reduction or lifting of pulse import tariffs after Trudeau’s visit. However, the two leaders did agree to sort out new and predictable rules governing exports of Canadian pulse crops by releasing a joint statement for our two countries to reach a new arrangement on pest-free pulse shipments before the end of 2018.

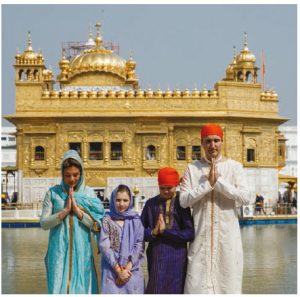

The tariffs might have been in reaction to Trudeau’s good relationship with Canadian Sikhs and the fact that all four of his Indo-Canadian cabinet ministers are of the Sikh faith. The sore point is that some Canadian Sikhs support the idea of Khalistan as a separate Sikh state.

Tensions between Canada and India aren’t new. Canadians were horrified in 1985 when violence between the Indian army and Sikh separatists spilled over into Canada through the bombing of an Air India plane, killing all 329 people aboard. The largest terrorist attack in Canadian history, it was thought to be retaliation against India’s government for its army’s seizure of Sikh militants in the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Canadians value multiculturalism and diversity, and recognize human rights, social justice and reconciliation. It is thus difficult for us to understand India-related conflicts that arise in Canada, especially those concerning the tragedy of Air India Flight 182.

Friction between successive governments of India and some Canadian Sikh organizations has persisted for some time. Past and present Canadian cabinet ministers have perhaps unfairly been tagged as sympathetic to the Khalistan independence movement, which is seeking a separate Sikh state.

Recent problems include the passage last April of a motion by Brampton-Springdale MPP Harinder Malhi in Ontario’s legislative assembly that recognized the 1984 events in India that killed more than 2,500 people as genocide; and the problem-laden trip by Canada’s defence minister, Harjit Sajjan, to his native Punjab on a mission intended to strengthen Canada’s bilateral relations.

Trudeau then offended the Modi government by appearing last May at a Toronto Sikh event that displayed separatist flags and posters depicting a Sikh leader killed in the 1984 military operation.

In addition, the election of Jagmeet Singh last October as leader of the federal New Democratic Party exacerbated tensions, particularly as Singh, a Sikh, was denied a visa by the Indian government in 2013 when he was an Ontario MPP.

The view in New Delhi seemed to be that there had been a resurgence in pro-Khalistan independence activism in Canada since Trudeau took office in late 2015. For years, Indian officials have tried to pursue initiatives designed to win Canadian Sikhs away from support for Khalistan independence.

On his inaugural trip to India in February, Trudeau, Sajjan and others met with Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh, a Sikh, trying to repair their strained relationship. Like Modi, Singh decries the actions of Sikh separatists. Prudently, Trudeau stressed throughout his visit that Canada supports a unified India.

But the trip was already mired in tension when the Canadian government hosted a reception to which it invited Jaspal Atwal, a former member of a banned Sikh terrorist group convicted in 1987 of the attempted murder of an Indian cabinet minister who was visiting Vancouver Island. In response, Mulroney writes that the debacle might “prompt a review, if not a complete rethinking of a Canadian foreign policy that [is] seriously off the rails. We have some hard lessons to learn…. [It] should encourage smart people in Ottawa to zero in on what isn’t working.”

Noting that the world is changing in ways that do not align with traditional Canadian views, interests and values, Mulroney continued: “If we’re smart, the rise of countries [such as] China and India can … contribute to our prosperity, and with hard work, we should be able to find common cause on important issues such as global warming…. But the rise of these assertive and ambitious Asian powers will almost certainly challenge global and regional governance and human rights and neither [country] will be particularly squeamish about interfering in Canadian affairs.”

A remaining and unresolved key issue is the revised Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was intended to create a unified counterbalance to China’s regional strength and to magnify the trading capacity of democratic nations having the rule of law, social market economies, fair trade and freedom of the seas values, some of which Trudeau voiced in Beijing last December.

India, Japan and the countries that are party to the new Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), including other regional democracies, are still the best major trade options for Canada and the U.S. in Asia and the Pacific Rim, even though the CPTPP has been shunned by the Trump administration. A future administration in Washington will probably reverse Trump’s decision to opt out, but, in the meantime, Canadians must vigorously advance their interests in the Asia-Pacific.

David Kilgour was secretary of state for Asia-Pacific in Jean Chretien’s government and an Alberta MP for almost 27 years. Janice Harvey is a retired secondary school teacher specializing in English as an additional language and in multicultural education.