In the global race to increase trade with China, Canada is still far behind many other industrialized nations. It has been a long, winding and often rocky path to get to a much more substantial exchange of goods, services and intellectual property.

Simply put, enhanced trade between the two countries remains a major work in progress, decades after talks began to open new commercial channels.

The initial signs of inroads — limited as they were in the earlier stages of commercial engagement with China — first appeared with Canada’s wheat exports in the 1960s and were later expanded after Canada recognized mainland China’s government in 1970. Since then, and despite many positive advances, commerce between the two countries has ebbed and flowed to the point where Canada is now losing out to other developed countries. Australia, which bears many similarities to Canada, has benefited, not just from its close proximity to China, but also from its efforts to break down other barriers to trade in Asia.

By 2015, Australia had completed free-trade agreements with its three biggest export markets — China, Japan and South Korea. At the same time, Canada has struggled to ink many major trade pacts within the Asian region.

This remains a huge disappointment and reflects a critical failure in policy. Given our history of engagement, Canada should be uniquely positioned to forge new partnerships with China. Instead, we find ourselves playing catch-up with other major economies, or — even worse — not being in the game at all.

We need to show that we are serious. We need to play to our strengths in critical areas of energy and other resources,

investment, value-added services and agri-food. These sectors are crucial to China’s future economic development and they present a wide range of opportunities, if we are wise enough to capitalize on them.

The most recent trade tally shows a five-fold increase in Canada’s bilateral trade with China over the past 15 years. That figure is substantial, but certainly not as substantial as it could be. By 2030, a free-trade pact between the two countries could add as much as $7.8 billion to our gross domestic product and create as many as 25,000 jobs over the same period.

Still, there is an imbalance. Chinese exports to Canada in 2015 grew by nearly 12 per cent to $65.6 billion, while products originating from this country and destined for China amounted to slightly more than four per cent of our total shipments for a value of $20.2 billion.

China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner, but China is far from being among Canada’s largest customers.

A recent study by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce titled Canada’s Business Checklist for Trade Negotiations with China illustrates how Canada earned a privileged relationship with China in past decades by engaging the developing giant, while many others chose to isolate and exclude the country of 1.4 billion people. In recent years, however, the rest of the world has made a priority of building a closer relationship with China, while Canada projected ambivalence, allowing our earlier advantages to be lost.

The uncertainty overshadowing Canada’s other key trade relationships means we can no longer afford ambivalence when it comes to our economic relationship with China. The cloudy future of NAFTA and the still-to-be determined impact of Brexit on the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the EU forces Canada to rethink our global trade policy.

While the revamped Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) will provide Canadian businesses with market access to more than 500 million people in the Asia-Pacific region, Canadian companies cannot turn away from the region’s biggest economic player — China. Now, more than ever, it is critical that Canada redouble its efforts to expand two-way commerce with the world’s No. 2 economy.

That will not be an easy task, as history has shown.

According to the Institute for Research on Public Policy, despite a steady stream of ministers and provincial premiers visiting China each year, Canada is not taken seriously. The criticism is that Canada’s relationship is narrowly focused on commercial interests, the IRPP said in a November 2015 study, which argues that a bilateral relationship cannot be effective without regular high-level political engagement.

As well, we need to focus clearly on the positive economic impact of nation-to-nation co-operation, not simply on the possible differences in their cultures and political systems. There is plenty of room for us to engage China on a wide variety of issues, ranging from the environment to human rights, but we need to understand that a country of almost 1.4 billion people is unlikely to change its domestic policies to gain access to our market of 36 million. Ultimately, we will have to make our decision on whether a trade agreement between our two countries is in Canada’s interests or not.

To quote the IRPP study: Canada should be looking closer at the Australian model “to see what a deeper approach might look like.” That country “has developed an influential role in the region far out of proportion to its economic size — its economy is one-third smaller than Canada’s.”

“Almost 30 years ago,” the report continues, “the Australian government initiated a major economic and political study of northeast Asia’s prospects. The resulting report to the prime minister in 1989 painted a clear picture of the region’s potential and recommended far-reaching policy changes that were followed through at the highest political levels and by successive governments regardless of party.”

However, even for Australia, this relationship-building has not happened without woes. It seems inevitable that, when dealing with such a behemoth economy where government still controls a substantial portion of business investments, there would be growing pains. Last year, Australians banned foreign political donations and strengthened anti-espionage laws, decisions aimed at curbing Chinese influence in their country. Without necessarily requiring the same level of legislation, Canada has to be ready to face the same challenges if it plans to go down the same route.

That said, the importance of China’s economy and its impact on global trade — and on Canada, in particular — is without question.

In fact, China’s growth trends have been a concern for several years — not because of declining levels in gross domestic product, but due to worries over a possible overheating of the economy.

Beijing officials have yet to clarify whether they will lower GDP growth targets in the coming year, and by how much. What we do know, at this stage, is that the country’s long-held goal is to double its 2010 level of GDP by 2020.

However, Art Woo, a senior economist at BMO Capital Markets, recently noted that China’s projections point to an annual growth rate of about 6.3 per cent over the next three years — between 2018 and 2020. Even so, there are concerns that the country’s hot credit growth will still manage to outpace economic growth in the coming years.

Nevertheless, there is reason for hope that progress toward improved economic ties and sustainable growth will eventually pay off with significantly increased trade between Canada and China.

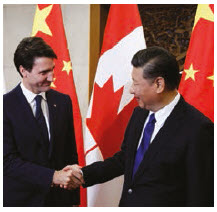

Steps are now being taken to redress our relationship with China. In the past two years, there have been considerable advances in the Canada-China relationship. In particular, we have seen reciprocal visits and negotiations at the highest levels of both governments that hold out the promise of a more productive relationship

In particular, both governments have expressed the desire to double bilateral trade between Canada and China over the next 10 years. Such a result would be well worth the decades of negotiations focused on solidifying co-operation between both countries.

Perrin Beatty is president and CEO of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.