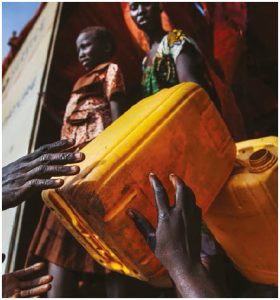

Last November, Allan Rock visited northern Uganda in the areas adjacent to the South Sudanese border, where refugees fleeing the brutal conflict in South Sudan have settled. What he learned during his discussions with refugees, UN officials and local representatives of international humanitarian and relief agencies is truly remarkable. It is, to be sure, a story of tragedy and untold human suffering arising from South Sudan’s brutal and destructive civil war. But it is also one of hope, compassion and the exercise of real political leadership.

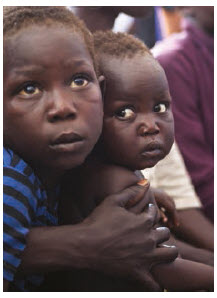

Today, Uganda hosts the highest number of refugees in its history — more than any other country in Africa and the third-largest number globally. Among the 1.3 million refugees in Uganda, 82 per cent are women or girls and 61 per cent are children.

While the vast majority of refugees (more than a million as of Oct. 31, 2017) arrived from South Sudan, Uganda also hosts refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (236,572), Burundi (39,041) and Somalia (35,373).

What has made the influx of South Sudanese refugees especially challenging has been the suddenness of their arrival. More than 330,000 arrived from South Sudan in 2017 alone.

Although the flow of refugees from South Sudan has slowed recently (to about 450 per day, down from an average of 2,000 per day in July and August 2017), the situation remains dynamic and unpredictable. Shifts in the location or intensity of the fighting in South Sudan can cause sudden spikes in arrivals.

Uganda proudly describes its refugee policy as “an open door.” It places no limit on the number of refugees it will receive. Refugees have full rights of mobility within Uganda. They can work without restriction. They reside in “settlements,” not “camps.” Refugees have access to education, health care and other social services on the same terms as Ugandans. Each refugee family is given a plot of land 30 metres by 30 metres to live on and, where possible, to cultivate.

Uganda’s enlightened approach to hosting refugees results in large part from its people’s own experience. There have been occasions in the past when Ugandans were forced to flee to neighbouring countries. Many described the current situation as being “our turn” to provide a haven in their neighbours’ time of need. One official from Uganda’s office of the prime minister poignantly recalled that he spent 10 years as a refugee in what is now South Sudan before returning to Uganda with his family in 1988, once order had been restored.

However, some of these very positive features of Ugandan policy remain more theoretical than real. For example, despite the freedom of mobility, the vast majority of refugees remain in settlements, with only about 100,000 having found their way to urban centres — primarily the city of Kampala. And while the gift of land is generous, that land is not always arable. Much of the territory north of the Nile is rocky and unsuitable for planting. Finally, the right to attend school means little for adolescents when there are few, if any, secondary schools available.

In fact, the benign environment created by the Ugandan refugee policy is betrayed by the significant shortfall in resources needed to make that welcome a reality.

By the end of 2016, the operations of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Uganda received only 37 per cent of the funding required for that year. It seems that 2017 saw a similar shortfall. Close to year’s end, UNHCR’s Ugandan operations were only 38 per cent funded ($215 million US out of $568 million US requested).

Uganda’s problem is but a microcosm of the larger problem the global community now confronts.

The world has the greatest number of refugees since the Second World War. There are now 22.5 million refugees worldwide — half of them under the age of 18. Frontline states, those on the borders of countries from which refugees are coming, are usually poor states themselves, yet they receive 84 per cent of the total number of refugees worldwide.

Unlike Uganda, many countries, including several in the developed world, are not honouring their commitments to assist refugees under the international refugee convention of 1951. Some countries won’t take refugees, nor are they prepared to step up to the plate to help those countries that do. Calls for more money to help UNHCR and refugee-hosting countries have gone unanswered, while existing pledges of financial support often go unfulfilled.

“We finance refugee assistance as if it were a charity ball,” says Lloyd Axworthy, chairman of the World Refugee Council, which was established by the Centre for International Governance Innovation with financial support from the government of Canada to examine what kinds of structural reforms are needed to make the global refugee system function better:

Some countries also want to send refugees home before it is safe for them to do so. In others, terrorist groups are exploiting refugees for their own partisan ends. In Lebanon, for example, Hezbollah has taken over the return of Syrians, sending them to areas where they are recruited as human shields and to establish territorial eminent domain.

Since the refugee crisis in Syria and North Africa first erupted five years ago, the European Union has struggled to manage its impact. Some countries, such as Germany, Italy, Greece and Turkey were initially welcoming and opened their borders to the refugee influx, while others, such as Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, turned them away. But the welcome mat is now being rolled up as Europe’s leaders confront a growing backlash from their own citizens, even in countries such as Germany, because of the fear that governments have lost control over their countries’ respective borders.

Refugees have become part of the anti-globalization, nationalist populist narrative that has arisen in Europe and elsewhere. Even a Western democracy such as Australia, once a champion of refugee rights and legal due process, is denying refugees asylum, putting them in camps on remote islands in the South Pacific where living conditions, according to many informed observers, are deplorable and sub-human.

Refugees also now spend longer in exile than ever before. In the early 1990s, it took an average of nine years to resolve the displacement of refugees. Today, that average is almost 20 years.

However daunting the refugee challenge may seem, it is one that is manageable. Even at their current record number, refugees comprise a tiny percentage of a global population that now numbers an estimated 7.5 billion people.

Structural reform of the global refugee system is essential, though not easily achieved. The most urgent features of that reform are long overdue: new funding mechanisms that are not dependent on voluntary contributions; each country paying its fair share; and a level of resources for refugees and host countries that is stable and predictable. The global refugee system also needs new oversight and accountability mechanisms that strengthen state obligations and ensure better state compliance with existing convention commitments.

Political accountability is not simply a downstream problem, however. It also runs upstream to those states that are responsible for the crises that create refugees in the first place. Such crises do not simply “happen.” Refugees too often result from violence, political persecution and other human rights abuses by dictators and despots whose own citizens flee in search of safety and survival.

The United Nations Security Council clearly has a key role to play in holding bad leaders accountable for these crises. In a digital world, new internet-based technologies can also be used in creative ways to support the delivery of services to refugees and enable them to find employment. For example, in the Middle East, the United Nations World Food Programme successfully deployed one of the largest-ever uses of the Ethereum blockchain (an open-source computing program.) Thousands of Syrian refugees and internally displaced persons were given, via their cellphones, cryptocurrency-based vouchers that could be redeemed in participating markets.

Innovations such as Ushahidi, an app that uses crowd-mapping to identify in real time areas where displacement is occurring and assistance is needed, could also be more widely deployed. Platforms such as WhatsApp have revolutionized the sharing of information and communication for people travelling in search of refuge. Other Internet-based technologies can support educational programs and create entrepreneurship opportunities for refugees where either broadband or mobile services are available.

In all of this, we must also work to change the toxic political narrative around refugees. They are too often the easy scapegoats for racist populist parties whose leaders exploit the widespread erosion of confidence in globalization, free trade and the multilateral system to argue for closing borders, building walls and diminishing the role of international institutions and regional organizations.

Refugees are a remarkable asset, not only to societies such as Canada, with aging populations, but also to many developing countries where their skills and talents are much in need. Being stateless through no fault of one’s own is not a cardinal sin. Any kind of effective, global response begins with that basic understanding.

Allan Rock is the former president of the University of Ottawa and was minister of justice and health in Jean Chrétien’s government. He is a senior adviser to World Refugee Council. Fen Osler Hampson is the director of the World Refugee Council. He is also chancellor’s professor at Carleton University and distinguished fellow and director of global security & politics at the Centre for International Governance Innovation.