It’s a dramatic number — 258 million. It comes from the United Nations’ International Migration Report 2017 and represents the estimated number of “international migrants,” which the organization defines as individuals who live in a state other than their state of birth or citizenship.

They account for what the report calls a “relatively small share of the total population, compromising about 3.4 per cent of the world’s population in 2017, compared to 2.9 per cent in 1990.” But the technocratic spirit of this description threatens to deny the substance of what it describes. It essentially condenses 258 million people into a necessary, but faceless category that fails to capture the personal and political complexities of their individual journeys and their collective impact on our world.

While no account can give these individuals adequate voice, their stories speak to the diverse circumstances and conditions that have compelled them to risk everything, including sometimes life itself, in search of something better elsewhere, regardless of how elusive or illusory this possibility might be. They collectively continue to transform our world as part of larger processes that also include globalization and digitalization.

As the World Migration Report 2018 states, migration is a “complex phenomenon that touches on a multiplicity of economic, social and security aspects affecting our daily lives in an increasingly interconnected world.”

Migration, the report notes, has improved lives in host and receiving societies, affording “opportunities for millions of people worldwide to forge safe and meaningful lives abroad,” a point that could not resonate more given that global displacement is at a “record high.” Immigrants, meanwhile, enrich host countries through their labour, skills, talents, and entrepreneurship. Along the way, they deepen cultural diversity and global ties. Yet migration and migrants often encounter suspicion and social exclusion.

The story of humanity is the story of migration since the first humans left Africa, and the story of migration is a sequence of encounters between host and newcomer, between new and familiar, between hospitality and hostility, between integration and exclusion.

Migration can take many forms. It can be legal or illegal. It can be forced or voluntary. It can be the outcome of war or political repression. It can respond to economic conditions. It can generate feelings of sympathy and acts of generosity. It can generate rejection and hatred.

Perhaps nowhere has this dialectic, with its unpredictable dynamic, appeared more clearly in recent years than in Germany during the height of the refugee crisis of 2015.

That year, net migration to Germany topped 1.14 million — a 49-per-cent increase over the previous year, and the highest since the founding of the Federal German Republic in 1949.

Most of these arrivals came from the Middle East and were accordingly

unfamiliar with the German language, not to mention the norms and traditions of a Western society.

Their seemingly sudden arrival inspired a spontaneous Willkommenskultur (welcoming culture) that earned Germany accolades from around the world and eased — at least for a while — the ghosts of Germany’s past into the background.

But this helles Deutschland (light Germany) of self-sacrificing volunteers soon co-existed with a dunkles Deutschland (dark Germany) of anti-Islamic protesters whose radical fringes torched asylum homes. Well-documented events in 2016, such as the mass sexual assaults in Cologne on New Year’s Eve (officials investigated more than 500 sexual offences committed mainly by men from the Maghreb countries) and the death of 12 people attending a Christmas market in Berlin at the hands of an Islamist migrant who had slipped past authorities on numerous occasions despite his long rap-sheet, have since revised public opinion and political mood, which had already begun to shift following the November 2015 terror attacks in Paris that killed 130 people and wounded hundreds.

The days when German politicians would snap smiling selfies with Syrian refugees have long faded following the emergence of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), under the leadership of Alexander Gauland, as a credible political force. In fact, Germany, like much of Western Europe, is suffering a crisis of identity, amid reports of changing demographics.

It would therefore be a mistake to dismiss the conflicts that large and sudden migrations have triggered in many countries around the world.

They are the animating forces of Brexit, U.S. President Donald Trump’s election and a range of populist parties across Europe. But migration also has defenders, and this article will examine these various forces as part of a larger survey of migration across the globe. Specifically, it will look at migration patterns and issues on a continental basis.

This article tries to capture the challenges and opportunities of migration as comprehensively as possible by drawing on a wide range of resources, key among them the International Migration Report 2017 as well as the recently released World Migration Report 2018.

The International Migration Report finds that between 1990 and 2007, the number of international migrants rose by more than 105 million — or 69 per cent — with most of this increase taking place between 2005 and 2017.

Second, growing populations in the world’s developing regions — we’ll call it the South — have led to more migrants arriving in the world’s developed regions — we’ll call them the North — where migration has become an increasingly important component of population growth. But the pace of migration within the South now outstrips migration between the North and South. As the report says, 60 per cent of the increase in migrants reflects migration between countries in the South.

Third, migration is a generally positive phenomenon that promotes economic growth and international trade and the transfer of skills. In this context, the report notes that Northern America (a region that includes Canada, the U.S., Greenland and Saint-Pierre and Miquelon), Europe and Oceania (which includes Australia) would see their working populations shrink without migration.

This said, it is clear that the current climate favours critics of migration. Whether their arguments carry the day, however, remains uncertain. What follows is a regional breakdown of the global situation.

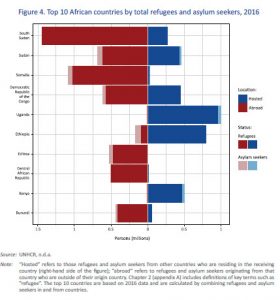

Africa

In 1990, a BBC drama eerily predicted the contemporary politics of African migration. The March tells the story of thousands, then millions of African migrants who trek across sub-Saharan Africa towards Europe to escape poverty compounded by climate change and corruption. Under the charismatic leadership of a Muslim cleric, the refugees eventually sail across the Strait of Gibraltar in boats, where they confront soldiers defending the ramparts of Fortress Europe.

Only a negotiated compromise that allows some migrants to enter, and the promise of a Marshall Plan for Africa prevents a military response. What makes the piece so profound is its nuanced treatment of the historical and contemporary factors that have pushed and pulled African migrants to Europe.

“We are poor because you are rich,” says the cleric in condemning European colonialism.

“The situation isn’t as simple,” responds a high-ranking official from the European Union. “We spend a lot of money on aid to Africa, but most of it never reaches the people who need it. We are not the only problem.”

Almost three decades later, images of African migrants storming the gates of Spanish enclaves in Morocco, or sailing across the Mediterranean in sagging ships, make it impossible to separate fact from fiction and current developments might offer more than a preview of far larger movements.

According to a 2011 Gallup poll, 33 per cent of sub-Saharan Africans said they wanted to migrate.

While the desire to depart does not automatically mean they will do so, it does not take much imagination to grasp the implications of this figure, if we consider Africa’s demographic profile.

The continent currently ranks as the fastest growing region in the world and scholars estimate its population will exceed 2.25 billion by 2050. So unless African states manage to mitigate local conditions, such as poverty, climate change and corruption, millions more will be on the move, following those who have already left.

“When people lose hope, they risk crossing the Sahara and the Mediterranean because it is worse to stay at home, where they run enormous risks,” warned Antonio Tajani, president of the European Parliament in July 2017. “If we don’t confront this soon, we will find ourselves with millions of people on our doorstop within five years.”

This said, the flow of African migrants into Europe has actually slowed down in recent years. According to the International Organization for Migration, 171,635 people arrived in Europe by boat in 2017, down by almost half compared to 363,504 in 2016. Looking at individual countries, Italy recorded the lowest number of arrivals from Africa in the last four years with slightly fewer than 120,000 people in 2017. Figures from Greece, Spain and other EU member states paint a similar picture.

Various measures account for this development. Those include programs designed to curb human smuggling, repatriation, economic development and, controversially, a deal between Italy and Libya, one of the major transit countries for migrants from major source states like Sudan, Somalia, Mali and Nigeria. Under the agreement, Italy, backed by the European Union, assists Libyan authorities to intercept and detain migrants. The deal has drawn considerable criticism from human rights advocates, including none other than the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein.

Hussein, like others, has lamented the deplorable state of the facilities that house detainees, an almost predictable outcome if we consider that Libya has found itself in the midst of a civil war since the violent overthrow of long-time ruler Moammar Gadhafi in 2011.

If Libya can barely govern its own people, how can it look after others?

According to various estimates, somewhere between 400,000 and one million migrants remained stranded in Libya as of December 2017. The absence of governing authority has accordingly allowed criminals to exploit these individuals. A viral video shows stranded migrants being sold as slaves. Libya, in the words of the International Organization of Migration, has become a “torture archipelago.”

This discovery generated some action by European and African officials, but little sympathy among Europeans, who have become increasingly indifferent towards nearly daily reports of drowning migrants. In fact, non-governmental groups such as Jugend Rettet (Youth Saves) have faced charges from anti-immigration voices of aiding and abetting human smuggling operations by rescuing migrants.

These NGOs, in turn, have refused to follow Italy’s code of conduct, which they consider uncaring and cynical. In fact, they have accused the Italian government of criminalizing life-saving measures.

While laudable on humanitarian as well as economic grounds — migrants send back remittances to their home countries and fill labour needs — proposals to legalize migration from Africa face tough political opposition from European populists, who would like to see less, not more, migration of any kind.

Others, meanwhile, are wondering whether it is ethical for Europe to recruit the best and brightest from Africa, where they would make a bigger difference if they remained.

These concerns leave decision-makers with few appealing choices.

They could quasi-militarize more than 3,000 kilometres of Mediterranean shoreline, following the Australian approach. This solution, while drastic, could deter illegal migrants, but would also produce ugly images that would rapidly undermine the self-image of Europe as a community of humanistic values. History also suggests that barriers — regardless of their size and strength — will ultimately succumb.

Or Europeans could increase their contributions towards Africa to deal with the root causes of migration with the understood risk of seeing their funds disappear into the dark accounts of corrupt African strongmen. This solution, while fraught if not executed properly, would be more sustainable, but also requires a longer commitment that would extend far beyond the immediate political horizons of European leaders.

Success also depends on the willing co-operation of African elites, who have become increasingly less inclined to accept European tutelage as China continues to pump significant resources into Africa without making pesky moral demands.

In short, migration will shape relations between Africa and the rest of the world — specifically Europe — for the foreseeable future. Both sides will likely have to confront some harsh truths about each other, not unlike the characters in The March.

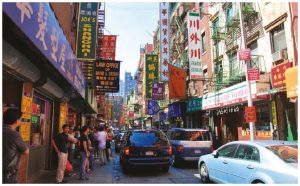

Americas

As the International Migration Report 2017 says, the geography of migration is highly uneven. In 2017, 51 per cent of all international migrants in the world were living in only 10 countries, with the U.S. taking the highest number.

The U.S. hosted 49.8 million migrants in 2017 or 19 per cent of the world’s total. For the record, Saudi Arabia and Germany hosted the second and third largest number of migrants with 12.2 million each, followed by the Russian Federation (11.7 million), the United Kingdom (nearly 8.8 million) and the United Arab Emirates (8.3 million.) The United States’ share of global migrants reflects its perceived status and self-image as the land of opportunity.

Unless they can claim 100 per cent Native American ancestry, the roots of all contemporary residents of the United States lie elsewhere, and the United States continues to draw migrants to its shores.

This human geography reflects the pull of the United States, where five out of the 10 largest bilateral migration corridors in the world terminated between 1990 and 2000.

The largest of those was the route between Mexico and the United States, which more than 500,000 people travelled annually between 1990 and 2000.The respective migration routes between the United States and India, China, Vietnam and the Philippines also cracked the Top 10 between 1990 and 2000.

While much has changed since then, three of the 10 largest bilateral migration streams still terminate in the United States. Between 2010 and 2017, about 80,000 people migrated annually from India, Mexico and China respectively to the United States, according to the 2017 International Migration Report. While the report does not identify their status, Mexicans have historically constituted the largest group of illegal immigrants to the United States.

The Pew Research Center estimated the number of illegal immigrants in the United States at 11 million in 2015, of which Mexicans accounted for 51 per cent. (This said, their numbers have shown a downward trend).

Yet it would be a mistake to single out one group. After Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, the largest group of illegal immigrants (268,000) comes from China, followed by India (267,000).

All of these arrivals — legal or otherwise — have contributed to what demographers call the “browning” of the U.S.

A Pew paper published in 2008 predicts that the population of the United States will rise to 438 million in 2050, from 296 million in 2005, and 82 per cent of this increase will be due to immigrants arriving between 2005 and 2050 as well as their U.S.-born descendants. Immigration, in other words, will account for 117 million new people by 2050. Of these, 67 million will be immigrants themselves and 50 million will be their U.S.-born children and grandchildren.

In fact, nearly one in five Americans will be an immigrant in 2050. As for the non-Hispanic white population, it will increase more slowly than other racial and ethnic groups. Under this scenario, the white population will become a minority by 2050, according to the predictions of the Pew Research Centre.

This demographic trend towards a “plurality” nation in which no single group will constitute a majority has caused considerable unease among sections of American society who fear migrants will hurt their economic prospects, introduce crime or undermine American culture — fears largely unjustified.

Consider crime. Yes, illegal immigrants to the United States have and continue to commit crimes of various kinds, including rape and murder, but at rates lower than the general population. The Department of Homeland Security estimates 1.9 million non-citizens living in the United States — whether legally or illegally — have committed crimes. The Migration Policy Institute has estimated that 820,000 of those people were in the country illegally, including 300,000 with felony convictions. This figure means about three per cent of the total undocumented population in the United States has committed felonies. But the share of felons in the overall population is twice as high, at six per cent, according to the Population Association of the United States.

Facts such as these have, of course, not stopped Trump from railing against immigrants. But if we accept the theory that Trump’s election represents a reaction to the “browning” of the United States, it clearly confuses noise with signal.

Canada, like the United States, has undergone a comparable transformation. According to the 2016 census, 21.9 per cent of the Canadian people (about 7.54 million) described themselves as landed immigrants or permanent residents, the second-highest share of all time after the census of 1921, when 22.3 per cent of the population qualified as foreign-born.

The source of migrants has fundamentally changed. In Canada’s first census in 1871, almost 84 per cent of its foreign-born population came from the British Isles. A hundred years later, people born on the British Isles still accounted for the largest share with 29 per cent, but dropped as the share of arrivals from other parts of the world increased. In 2016, people from the British Isles accounted for seven per cent. What happened? Changes in policy coupled with increased mobility have fundamentally changed the sociological profile of migration patterns in Canada.

In 2016, almost half (48 per cent) of the total foreign-born population was born in Asia (including the Middle East), while a lower proportion (27.7 per cent) was born in Europe. Looking at the number of newcomers between 2011 and 2016, 61.8 per cent were born in Asia.

Current trends point to the Philippines, China and India as the main sources of future immigrants, with Iran and Pakistan rounding out the top five immigrant source countries between 2010 and 2015.

Regions of the world that barely registered on census forms in the late 1960s and early 1970s (such as North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South America) are also growing, and growing fast, while the share of immigrants from the United States and various parts of Europe have first risen, then fallen between 1871 and the present.

Canadian society, unlike sizable sections of U.S. society, appears comfortable with this development. But some attitudes might be hardening, according to a recent poll that shows an increase in the number of Canadians (27 per cent), who have questioned rising admission levels as Canada prepares to accept 340,000 new arrivals by 2020. Another poll by Angus Reid also found that 57 per cent of Canadians agreed with the statement: “Canada should accept fewer immigrants and refugees.”

Looking beyond Canada and the United States, Latin America and the Caribbean remain source rather than destination regions. According to the International Migration Report, the corridor from Latin America and the Caribbean to North America was the third largest in 2017, with more than 26 million international migrants. However, this stream has been trickling off. Reasons include increased border enforcement, shrinking income gaps between Northern and Latin America, and demographic changes. Societies in Latin America are aging, thereby producing fewer younger people willing to travel across great distances. This said, the numbers are still substantial.

As the World Migration Report 2018 says, North America remains a migration destination. During the last 25 years, the number of migrants in North America has almost doubled thanks to population growth in Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia, as well as economic growth and political stability in North America.

Asia

Arguably no other continent has experienced the problems and causes of migration more fiercely than Asia. According to the International Migration Report, Asia recorded the highest number of international migrants between 1990 and 2017 — 31 million. Of these, 28 million (or 89 per cent) were born elsewhere in Asia. This high degree of movement within the Asian continent differs from Europe and Northern America. Of the 29 million migrants that Europe gained during this period, 46 per cent were born in Europe, 24 per cent in Asia, nearly 17 per cent in Africa and 12 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean. Of the 30 million migrants that Northern America gained, 55 per cent came from Latin America and the Caribbean, while 37 per cent came from Asia, and slightly more than seven per cent from Africa.

In short, Asia experiences external and internal forms of migration and the Asia-to-Asia route was the world’s largest migration corridor in 2017.

Looking at specific bilateral routes, six out of the 10 largest bilateral migration routes between countries move through Asia.

Familiar push and pull factors have contributed to this phenomenon.

First, high-income regions in Asia draw migrants from low-income regions.

That explains the stream of migrants from Southern Asia (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Bhutan among other places) to the oil-rich Gulf countries, where immense wealth and ambition coincide with a need for labour of every kind.

Between 2000 and 2010, three of the world’s largest bilateral streams of migrants ran from a country in Southern Asia to an oil-producing country in Western Asia: Bangladesh to United Arab Emirates (UAE), India to Saudi Arabia, and India to UAE. A similar pattern appears in the period between 2010 and 2017 (India to Oman, India to Saudi Arabia and India to Kuwait).

Migration streams of this sort have led to a regional transfer of wealth by way of remittances.

Total global remittances from migrants to their home countries in 2017 topped $450 billion — up by 4.8 per cent. India leads the list of recipient countries with $65 million and a closer look reveals that four of the five top source countries for remittances to India lie in the Gulf Region. In fact, remittances from Indians working in Saudi Arabia were almost on par with remittances from Indians working in the United States. Indian remittances from the United Arab Emirates led the way.

Migrants from Southern Asia working in Western Asia therefore represent an important economic lifeline back home. Consider Bangladesh, one of the poorest countries in the world, with a 2016 per-person GDP of $3,900. In 2015, Bangladesh received remittances of $15.8 billion.

But migrants from Southern Asia, specifically women, have also been victims of serious human rights abuses at the hands of their employers, often with little or no recourse.

Perhaps the most infamous example from the Gulf region is the deadly exploitation of migrant workers building the stadiums for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. In 2012, the Qatari government revealed 520 workers from Bangladesh, India and Nepal had died during construction work, including work on stadiums. Despite promises of serious reforms, unbearable heat coupled with regulatory indifference have continued to cause deaths on construction sites across the Gulf region. The World Cup construction site itself saw 10 related deaths between July 2015 and September 2017.

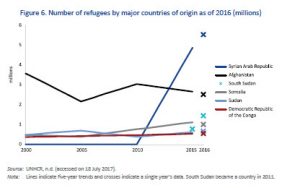

If parts of the Middle East attract migrants, others create them. More than 5.4 million Syrians have left their country since the start of its civil war in 2011, joining the millions of Iraqis, Afghans and others in the region, who had already left their respective homes to escape the ethnic and sectarian conflicts that have roiled it for decades, dating back to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan through to the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

While the migratory effects of the Syrian civil war on Europe have received considerable coverage, its regional effects have received less. About 3.3 million Syrians currently await their fate in Turkey, another million in Lebanon and another 650,000 in Jordan.

The vast majority of Syrian refugees in these neighbouring countries do not live in camps, but they nonetheless face various difficulties, including poverty, limited job opportunities, inadequate housing and discrimination by their host societies.

Perhaps worse, they face uncertainty. They live in places not far from their original homes, but the option of returning to a country shattered by war with few immediate prospects for recovery and stability will likely strike many as unappealing.

At the same time, they confront rapidly closing borders and growing hostility towards migrants, especially if they hail from the Muslim-Arab world.

In some ways, this experience previews what might happen to almost 700,000 Rohingyas, who fled Myanmar for Bangladesh in the fall of the 2017 during a “textbook example” of ethnic cleansing as Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights, described it.

As The Economist wrote in late 2017, their flight “was one of the most rapid international movements of people in modern history, eclipsing in intensity, for example, Syrians’ flight from civil war over the past six years.”

While a deal for their return is in place, confusing signals from Myanmar and warnings from UN officials have raised the possibility that their presence in Bangladesh might last longer than many would like.

Australia

“Our Adam and Eve had not been chosen by God, but by judges.”

That is how Thomas Keneally, author of A Commonwealth of Thieves, described the genesis of modern-day Australia as a British penal colony. Its story begins on Jan. 18, 1788, when a fleet of 11 ships carrying 734 convicted criminals and their 210 guards sailed into Botany Bay. But these “Founding Rogues,” as The New York Times called them, quickly deemed this site unsuitable for settlement and instead chose to settle at Sydney Cove on Jan. 26, 1788.

Generations of Australians have since celebrated that date as Australia Day, but not everybody has always joined in. Official celebrations have increasingly recognized Indigenous Australians, but many of the continent’s original inhabitants remain ambivalent, if not hostile, towards the date, because for them, it marks the official start of European colonialism.

The celebration has been a continuous source of controversy, one likely fed by former Australian PM prime minister Tony Abbott, who remarked in a January 2018 radio interview days before Australia Day that British settlement was a “very good thing” although “not immediately good for everyone.” Abbott also used the occasion to tell the government of his successor, Malcolm Turnbull, to spend fewer resources on fighting climate change while also scaling back immigration to ease the pressure on housing prices.

Abbott’s comments are consistent within a stream of Australian society that has been trying to curtail immigration. “The prime reason for the decline in living standards for many Australian workers is our staggering population growth,” said Dick Smith, an entrepreneur and philanthropist who wants to drastically reduce immigration to Australia under his Fair Go Campaign. Immigration has certainly fuelled Australia’s population growth. A total of 28 per cent of the population has roots outside of Australia and net overseas migration, which measures immigrants minus departing Australians, has nearly doubled since 2000.

Concerns about the economic effects of migration in Australia are also not unfounded. A government commission concluded in 2006 that immigration could lead to higher unemployment or slower wage growth, or both, for specific groups, especially those working in sectors with higher concentrations of immigrant workers. “Increased risk of displacement is more likely at the lower end of the skill spectrum and in the youth labour market,” states a 2016 government report titled Migrant Intake into Australia.

But overall migration has had neutral, if not positive, effects, that same report notes. While acknowledging “scant evidence,” it found that at an “aggregate level, recent immigrants had a negligible impact on wages, employment and participation of the existing labour force.” The report notes that local workers fear immigrants can reduce the wages of locals or displace them, a concept partially based on the fallacy that the number of jobs in any economy remains fixed. While migrants may displace locals into jobs with lower wages, that is not inevitable.

“Offsetting this effect is the increase in demand for local goods and services from new immigrants,” the report states. “Immigrants may also complement rather than displace local workers, improving productivity, particularly when filling skill shortages that are restricting the expansion of firms.” Young, well-educated migrants have especially benefited the Australian economy, whose workforce would shrink without them.

Looking beyond Australia’s current unemployment rate of 5.5 per cent as of January 2018, census data found recent migrants (especially if they lack English skills) struggle to find work. But on the whole, unemployment rates among foreign-born workers are only slightly higher than unemployment rates for those who were born in Australia and the share of foreign-born workers with jobs matches the share of native-born workers with jobs, according to OECD data, as interpreted by Australia’s Lowy Institute.

Australian society, for its part, has largely welcomed immigrants, who, according to the government commission, appear to be “well accepted” despite some fluctuations, thanks to Australia’s commitment to multiculturalism.

But the report also reveals contradictions. Recent surveys of temporary and permanent residents found that two thirds of those surveyed would like to limit Australia’s population to below 30 million — a figure Australia would reach by 2030 if current immigration rates remained steady. But only one third of the same survey respondents said immigration levels are too high.

Generally positive attitudes of Australians towards new arrivals have also become increasingly theoretical. Australians have found it difficult to purchase their own homes in desirable locations such as Sydney and Melbourne, with many would-be buyers grumbling about the influx of foreign investors, many of them of Chinese descent.

Research from Credit Suisse released in October 2017 found that foreign buyers accounted for 26 per cent of all new homes purchased between September 2016 and June 2017 in New South Wales, the Australian state that includes Sydney. Of those buyers, citizens of China and Taiwan accounted for 87 per cent. Overall, foreign buyers poured about $10 billion into three Australian states, a very small portion of the total real estate industry in Australia, which is valued at $6.7 trillion,

While these investors can only buy new homes, they have contributed to rising housing costs, compounding the effects of migration on housing.

Despite its continental size, Australians (both old and new) cluster along a few coastal cities and immigration has stoked housing prices. Sydney is one of the most unaffordable cities in the world, relative to income. At the same time, Australia’s real estate industry depends on foreign investors, and despite efforts by the government to discourage foreign investments, Australia remains one of the most desirable investment locations.

All of these aspects run the risk of being lost among a public increasingly fearful of foreign investors and amidst a debate about whether stated concerns about foreign investment from China amount to racism, a distant echo of the debate that unfolded during the late 19th Century, when the Australian government responded to an influx of Asian migrants with its 1901 “White Australia Policy.“

This debate further complicates the image of Australia in the immigration debate. On one hand, Australia consistently ranks among the most tolerant societies, notwithstanding xenophobic firebrands such as One Nation leader Pauline Hanson, who first warned of an Asian invasion in 1996, then turned her ire against Muslim migrants without genuinely abandoning her former positions about Asian migrants. She remains a minority voice.

On the other hand, human rights groups continue to criticize Australia’s long-running policy of mandatorily detaining anyone who enters illegally. This policy included, at one stage, two notorious offshore detention centres where asylum-seekers await their fates under often brutal, dehumanizing conditions.

One of those — the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, located on the South Island Nauru — has operated, with interruptions, since 2001. The second offshore facility — the Manus Regional Processing Facility located on the Papua New Guinean Island of Los Negros Island — closed in October 2017 after being in operation on and off since 2001.

Perhaps the most restrictive of its kind, the Australian detention system virtually shut down illegal migration streams during the first decade of the 21st Century, and continues to draw praise from European populists as a solution to the stream of illegal migrants arriving from Africa and elsewhere by boat. It denies refugees arriving by boat any chance of entrance to Australia.

“If you come to Australia by boat without a visa, you won’t be settled there. No way — you will not make Australia home,” billboards in neighbouring countries bluntly warn.

Supporters of this measure, which enjoys broad political support, claim that it discourages human smuggling, thereby saving lives, while critics such as well-known refugee advocate Julian Burnside and others claim that the measure is not just inhumane, but also illegal and ultimately ineffective, since most refugees arrive in Australia by plane, not boat. Questioning the professed Christianity of Australian political leaders such as Turnbull and Abbott, Burnside says their worries about drowning refugees are nothing more than a “fig leaf to make moral mistreatment look compassionate.”

Europe

Riffing off legendary country star Johnny Cash, Sweden’s former foreign minister, Carl Bildt, said in 2015 that a “ring of fire” surrounds Europe.

It includes revisionist Russia, which is ramping up various conflicts with its regional neighbours, such as Ukraine and Georgia, as well as failed and failing states in Africa. And then there’s a swath of the Middle East, stretching from Syria to Yemen, which is itself a crescent of catastrophic conflicts not seen since the European cataclysm of the Thirty Years War during the 17th Century.

What unites this rim of hostility? Shared pathologies include uncertain borders, stagnating economies, raging corruption and murderous regimes facing various challenges to their despotic rule by both moderate and radical forces.

Save for Russia, whose population has been declining for various reasons, this region has also experienced rapid population growth without delivering the necessary economic and political growth that would adequately satisfy its young, ambitious populations. In short, more people are chasing fewer opportunities in places that create few, if any.

Some have challenged the local status quo — see the Arab Spring — while others have voted with their feet by heading towards Europe, be it by sea across the Mediterranean or by land along the Balkan Route, now closed after the European Union signed a deal with Turkey that essentially entrusts the care of several million migrants to a man — Recep Tyyip Erdogan — whose governance style is as mercurial as it is authoritarian.

This influx of individuals into Europe from beyond its borders has encouraged Brexit, strained the resources of receiving societies (especially Italy and Greece, but also elsewhere) and fundamentally re-aligned European politics.

European parties no longer align themselves along the familiar left-right axis. They instead increasingly define and differentiate themselves by where they stand on immigration issues. Do they favour closed or open borders? Do they favour more or less money for measures designed to integrate migrants? Where do they stand on Islam, the majoritarian religion of migrants from outside of Europe, against concerns that central Islamic tenets clash with the social contours of contemporary Europe, an increasingly secular continent?

Questions of this sort have stressed European societies between Narvik and Napoli to the breaking point.

Current divisions with the European Union reflect this dynamic. Leaders of EU states in Central and Eastern Europe — Poland and Hungary among others — have openly refused to accept illegal migrants despite a valid agreement among EU members that the highest European court has since confirmed.

Notwithstanding appeals to their sense of solidarity and burden-sharing from voices of Western Europe, the governing elites of these post-communist states consider illegal migrants as threats to physical security and cultural survival even as they might benefit from migration in the face of shrinking populations as in the case of Bulgaria.

A chorus of Western commentators cutting across the ideological spectrum has effectively amplified these concerns.

Far-right commentator Douglas Murray, author of The Strange Death of Europe, warns of Europe falling victim to Islamofascism, a fear that receives a literary treatment in Submission by controversial French author Michel Houellebecq, who describes a not-so-distant dystopian Europe divided along racial and religious lines.

Far-left philosopher Slavoj Zizek accuses liberals of romanticizing refugees while downplaying the less appealing aspects of mass migration, such as rising crime rates and welfare fraud.

Feminist icon Alice Schwarzer fears migrants from Islamic countries will stoke misogyny, a point made by far-right populists who denounce refugees as Rapefugees.

European Jewish leaders, meanwhile, fear a new wave of anti-Semitism by way of migrants socialized in officially anti-Israel states that deny the Israeli state the right of existence.

What unites many of these voices is the belief that the worst is yet to come.

Gunnar Heinsohn, a German demographer whose academic credentials include teaching at the NATO Defence College, has argued that Europe faces the theoretical prospect of having to absorb 800 million refugees from Africa by 2050.

Ethnic-based prejudices can tie closely into political opportunity. Case in point is Hans-Christian Strache, leader of the Freedom Party of Austria and junior partner of the new Austrian chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, who belongs to the Austrian People’s Party. Not long ago, his party stood accused of promoting anti-Semitism, a charge that earned the party and Austria political shaming in the early 2000s.

Since then, though, it has directed its rhetoric against Muslim migrants and now serves as junior partner in a combined centre-right, far-right governing coalition already the norm in Eastern Europe.

Strache is therefore only the latest incarnation of a political archetype increasingly common in Europe: The thundering populist whose nationalistic rhetoric professes to speak for what Germans call kleine Leute, or ordinary people, increasingly uncertain about their future in a world reshaped by globalization, digitization and yes, migration — legal or otherwise.

This appeal does not automatically imply a recommendation for open borders. But it is an appeal for a basket of common European policies that gives millions of migrants inside and outside of Europe some prospects for a better future, whether they have already arrived or not.

The European continent, otherwise, risks descending into an inferno of its own creation.

Wolfgang Depner is a writer who lives in Victori. He writes about politics, and teaches at Royal Roads University. He also taught political theory and international relations at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus.