In August 2014, ISIS militants ordered Yazidi villagers from Kocho — a rural farming community in northern Iraq — to march in the sweltering heat to its only school. Women waited on the upper level of the school while men were assembled outside. Those who refused to convert to Islam were shot. From inside the school, the women heard loud gun shots that continued for an hour.

ISIS killed men with armpit hair, but spared some of the boys — those without armpit hair — because they figured they could brainwash them, turn them against their own people and train them to become young soldiers for the ISIS cause.

Women were then herded onto buses and separated into groups — older women were slaughtered, their daughters ripped from their arms and forced to become ISIS sex slaves.

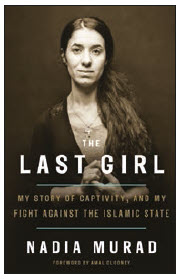

Six of Yazidi activist and author Nadia Murad’s nine brothers and her mother were executed and buried in mass graves. Murad was taken to the slave market in Mosul.

ISIS had begun its attempt to wipe out Yazidis in Iraq.

In The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State (Penguin Random House, $36), Murad shares her excruciatingly painful experience of being raped and tortured by ISIS militants. Murad’s first captor, Hajji Salman, who told her “Yazidis are infidels,” forced her into a marriage that meant he officially owned her. These “marriages,” Murad wrote, were the beginning of a slow murder of Yazidi girls.

ISIS has carried out or inspired more than 140 terrorist attacks in countries other than Iraq and Syria, according to a CNN analysis from February 2017. The attacks across the world have killed more than 2,000 people. Because of this, media attention is focused on attacks and victims in their own country, or neighbouring countries. To say there is less attention paid to the atrocities committed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria is an understatement.

ISIS has carried out or inspired more than 140 terrorist attacks in countries other than Iraq and Syria, according to a CNN analysis from February 2017. The attacks across the world have killed more than 2,000 people. Because of this, media attention is focused on attacks and victims in their own country, or neighbouring countries. To say there is less attention paid to the atrocities committed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria is an understatement.

In June 2016, two years after Murad had felt the impact of rape used as a weapon of war and after her village and other Yazidi villages in Iraq were captured by ISIS, the United Nations released a report identifying ISIS atrocities as genocide.

While ISIS closed in on the Yazidis, no one paid attention until it was too late. Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga fighters promised Yazidis they would protect them, but just before ISIS circled Murad’s village, the fighters fled. The Yazidis’ Arab and Kurdish neighbours, who largely looked down on the ethnic minority, also failed to help or protect them.

Murad clung to her faith throughout the roughly three months she spent in captivity. In The Last Girl Murad offers an education on the Yazidi faith and why it’s so loathed by ISIS.

Misconceptions about Yazidis

Yazidis pray to Tawusi Melek, an archangel who took the form of a peacock at creation, and painted an otherwise plain Earth with colours from his feathers. It’s a religion that combines Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism and Christianity.

Murad writes that Yazidis have been the target of genocide 73 times and explains that there are a lot of misconceptions about the religion and idiosyncrasies that people have a hard time understanding. Those include not showering on Wednesdays, or wearing the colour blue and avoiding eating lettuce. Their rituals and the fact that their religious stories are passed down orally — Yazidis don’t have a book as other religions do — fuelled ISIS’s hate. ISIS calls Yazidis “devil worshippers.”

After being raped and tortured for months, Murad escaped from the home of an ISIS militant who had surprisingly left her home alone. With help from a complete stranger, a young man named Nasser, whom Murad befriended after knocking wildly on a random door looking for help, she escaped Iraq and its militant-laden city of Mosul and found safety in Kurdistan. Nasser returned to Iraq after delivering her safely to the border. But her personal story of torture would soon be used against her by Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga fighters she met at a checkpoint. They forced Murad into telling her story on video, promising it would only be shared internally. They then released it to the media. The group that allowed the video to be broadcast was hoping to use it as a political tool to embarrass another group of Kurdish fighters who are their political rivals.

Murad began telling her story widely a year and three months after ISIS murdered and enslaved the residents of Kocho. She spoke at a United Nations forum on minority issues in Geneva, and less than a year later, she was named a goodwill ambassador of the UN office on drugs and crime, working for the dignity of survivors of human trafficking. Murad told the UN that she and other Yazidis want ISIS prosecuted for genocide.

“I told them that I wanted to look the men who raped me in the eye and see them brought to justice. More than anything else, I said, I want to be the last girl in the world with a story like mine.”

Having experienced the wickedly cruel acts of ISIS first-hand, Murad is best positioned to explain to the world how barbaric ISIS is to Yazidis.

Syria’s refugees and their fate

Syria’s refugees and their fate

The most disturbing story German journalist Maria von Wesler tells in her book, No Refuge for Women: The Tragic Fate of Syrian Refugees (Greystone Books, $24.95) came from a Yazidi refugee von Wesler met in Turkey.

Seve, a 42-year-old mother of eight, told von Wesler about how one year earlier, 20 people, including herself while pregnant, fled Iraq on foot heading for the Turkish border. She and her family eventually reached Diyarbakir, a city of 1.6 million, in eastern Turkey.

“The gruesome images of the beheaded neighbour, the murdered children, were fresh in her memory,” von Wesler writes of Seve’s personal experiences at the hands of ISIS fighters. She told von Wesler: “‘They cooked them’…. ‘And then they forced us to eat the soup’.”

Von Wesler writes that her translator could hardly speak those words, though she doesn’t elaborate on the cannibalism. The writer also explains how reluctant Yazidi women are to seek refuge in Turkey because they are terrified of Muslims — particularly in this region — where Muslims carried out a genocide against Yazidis a century ago. It was hard for Yazidis to reconcile the Turks’ hospitality now with their actions 100 years ago.

Von Wesler says she started writing her book after questioning why, in all of the TV images of men in dinghies crossing Turkey to the Greek islands, and of those trudging through the Balkan route, there were few women alongside. She visited refugee camps in Turkey, Jordan and Greece and informal settlements in Lebanon and documents those women’s stories in her book.

For Syrian women who have fled Bashar al-Assad’s cruel regime, the terror of ISIS and the inevitable crossfire from rebel forces, finding refuge in a neighbouring country is often the only option. But what observers fail to realize when they watch refugees flood borders in Europe and hear of thousands of refugees living in camps, is that women and children make up the majority of those in tents, caravans or small apartments. Their husbands, brothers and fathers are fighting, have been killed, or have made the trek to Europe in advance of their families.

Having visited refugee camps in Jordan and Greece, von Wesler’s experience sounds familiar — I, too, asked “What happened to your husband?” And received the same response.

The book opens with Miryam, a Syrian refugee von Wesler met in Hamburg.

“She holds her bleeding child in her arms. Akilah, 17, has been badly hurt,” the chapter titled “Syria” begins. Miryam’s story starts in the fall of 2014 when al-Assad’s forces dropped barrel bombs on her neighbourhood, Kafr Sousa, a suburb of Damascus where there is strong resistance to government. It was when Miryam rushed her 17-year-old daughter to the hospital in a wheelbarrow that she realized al-Assad was bombing his own people. For her part, von Wesler remarks that most of the Syrian refugees she meets in Germany tell her they fled al-Assad, not ISIS.

After Akilah, their eldest daughter, was injured, Miryam and her husband decided it was time she and their five girls left home. Miryam’s husband was promptly arrested and put into a military camp, which is a sad, but familiar tale for many Syrian women.

In Hamburg, Miryam tells von Wesler about her relationship with her husband. Von Wesler takes some liberties by including her own opinion about Miryam’s relationship. For instance, after Miryam tells von Wesler she was in charge of cooking and cleaning, but that if she didn’t do those chores, her husband wouldn’t complain, von Wesler wrote, “Who knows, I wonder, if that really was the case?” Perhaps some readers would be interested in von Wesler’s perspective, but including a line about how Miryam — or Syrian women — may not want to speak openly about their love life with a stranger would have been more powerful.

Over the course of her travels, meeting and interviewing Syrian refugees, von Wesler visited Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and Lesbos, an island in Greece. In addition to sharing Syrian refugees’ stories with the reader, von Wesler also includes statistical data for each country and what its contribution toward the refugee crisis has been.

The book concludes with the second part of Miryam’s story, which begins on an Italian rescue boat with 150 other refugees and ends in a container settlement where she’s now living in Hamburg.

Overall, von Wesler does a superb job sharing the stories of many Syrian refugee women across the Middle East and Europe who are raising their large families without the support of their husbands. As the Syrian civil war enters its seventh year, we’re reminded of the lives that have been lost and the women who are left behind.

Six books to read this spring

Women and the War on Boko Haram: Wives, Weapons, Witnesses (African Arguments)

By Hilary Matfess

Publisher: Zed Books

Price: $20.70

In 2014, the ISIS militant group Boko Haram captured 276 school girls, shocking the world and sparking one of the largest social media campaigns, with people all over the world tweeting the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls.

In Women and the War on Boko Haram, Matfess describes how Boko Haram’s violence against women and girls goes further than the abduction of the girls from the school in Chibok. She writes that Boko Haram has, similarly to ISIS in Iraq and Syria, enforced religiously sanctioned marriage in order to exploit and sexually assault women. Matfess describes what she learns through her fieldwork in the region in her account of Boko Haram’s impact on Nigerian women. She also focuses on the Nigerian and Western governments, which failed to prevent Boko Haram’s violence against women. Matfess also dismantles many stereotypes, writing that these women are not all victims. Indeed, many Nigerian women chose to join the group.

The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa

By Kate Baldwin

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Price: $30.47

Kate Baldwin examines how unelected traditional African chiefs can impact democracy in The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa. Baldwin writes about the interesting dichotomy between traditional chiefs and elected politicians, and argues that politicians can primarily only respond to their rural constituents through institutions maintained by local leaders who don’t have to worry about their electability.

Baldwin also writes about how chiefs hold significant influence over politicians during elections because of their status within their own communities and, most notably, their unique ability to bring development projects to their regions.

Crude Nation: How Oil Riches Ruined

Venezuela

By Raul Gallegos

Publisher: Potomac Books

Price: $24.56

While the world’s attention is largely turned toward the refugee crises in the Middle East and Myanmar — there is a massive humanitarian crisis just south of North America.

The lowest estimate of Venezuelans to have fled the country for Colombia sits at 500,000. As recently as February 2018, Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland said Venezuela is sliding “deeper into dictatorship” and Venezuelans are continuing to suffer under President Nicolás Maduro.

Raul Gallegos writes in Crude Nation: How Oil Riches Ruined Venezuela that the Venezuelan government’s use of oil money to subsidize life for its citizens, while regulating every aspect of their day-to-day life, has created a world in which citizens can fill their vehicles for less than one American dollar, but no longer have access to staples such as milk and sugar.

Gallegos, a senior analyst for a consulting firm called Control Risks, has written extensively about the topic. Gallegos is well-positioned to give readers insight into the government mismanagement that has led Venezuela into chaos, which is now seeing residents take desperate actions, such as putting their children up for adoption. He was previously an oil correspondent with Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal.

The Lost City of the Monkey God

By Douglas Preston

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Price: $22.97

American journalist and author Douglas Preston joined a team of scientists in 2012 in search of the rumoured lost city in Honduras called the White City or the Lost City of the Monkey God.

Rumours have circulated for centuries that a lost city, full of wealth, was buried beneath dense rainforest canopies in the Honduran interior. In 1940, a journalist reported that he found hundreds of artifacts in the Lost City, but he killed himself before revealing its location. Years later, Preston and a team of scientists, using highly advanced technology, mapped the terrain beneath the rainforest, which revealed an image of a lost civilization. But upon returning from their journey, Preston and others in his group learned they had contracted an awful, sometimes lethal disease.

The story of Preston’s journey is full of suspense and offers an education about an amazing discovery.

We Do Not Have Borders: Greater Somalia and the Predicaments of Belonging in Kenya

By Keren Weitzberg

Publisher: Ohio University Press

Price: $32.95

Many Somalis who have lived in Kenya for decades are abused by locals. They are seen as dangerous outsiders, despite having lived there for many years, some before the country was even established. Keren Weitzberg explores the historical factors that led to the ongoing discrimination against Somalis in Kenya. Weitzberg’s book is particularly relevant given the terror attacks carried out by the Somali-based militant group al-Shabaab in Kenya in recent years.

Rwandan Women Rising

By Swanee Hunt

Publisher: Duke University Press

Price: $39.49

Swanee Hunt, a former U.S. ambassador to Austria, documented the stories of roughly 70 women in Rwanda who overcame brutality and suffered massive losses during and after the Rwandan genocide.

Hunt, who’s also the founding director of the women and public policy program at Harvard’s Kennedy School, has worked with women around the world. She writes that Rwandan women organized around everyday issues such as housing and health care to improve Rwanda in the aftermath of the horrific genocide.

Today, 64 per cent of elected parliamentarians in Rwanda are women. Hunt argues that women played an unparalleled role in Rwanda’s recovery.

Janice Dickson is an Ottawa-based political reporter who covers foreign affairs and immigration for iPolitics.