Africa no longer feeds itself. Forty years ago, sub-Saharan Africa’s then 500 million people could grow enough staples — maize, wheat, rice, yams, cassava, sorghum, millet and the ancient grain known as teff — to keep most inhabitants free from hunger. But now there are about 1 billion sub-Saharan Africans and soon there will be 2 billion and, by 2021, predictions suggest more than 3 billion.

This Malthusian moment is exacerbated by the intensification and unpredictability of climate change. As the world grows warmer, it becomes prone to extreme weather events and radical changes in what once were steady and recurrent seasonal rotations. The intertropical convergence system, which once reliably brought rain to inner Africa at predictable times, now no longer does so. Further, the annual monsoon rains arriving across the Indian Ocean may or may not recur as they once did.

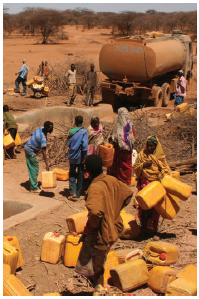

Drought is an ever-present danger, as well. The Sahel and northeastern Africa has suffered from recurring shortages of rainfall, and consequent starvation, several times since the 1970s. Even southern Africa, the sometime breadbasket of the continent, now is prone to excessive periods of drought. Or sometimes there is too much rain at once, which the nutrient-poor soils of sub-Saharan Africa cannot absorb.

The African continent has 65 per cent of the globe’s arable land that is available for cultivation, but currently lies fallow. If cultivated even marginally, that much land could help feed the millions of Africans who depend, as they must, on food imports, usually from the Americas or Asia. Overall, Africans spend at least $35 billion US a year on imported food while exporting almost no agricultural produce. When there are many more Africans, by 2025, the African food import bill is anticipated to rise to at least $110 billion US.

Since traditional agricultural pursuits in sub-Saharan Africa are rain-fed, climate anomalies obviously make production much more difficult than in earlier decades. Very little — about 3.6 per cent — of African agriculture is irrigated with Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, boasting only 1 per cent irrigation cover for its array of vastly different soils and farming practices. Even in wealthy South Africa, irrigated lands (usually controlled by conglomerates) account for only 1 per cent of all farmland.

Fertilizer use has greatly declined throughout sub-Saharan Africa since the 1970s, largely because of cost, but also because its distribution has depended on poorly managed state-controlled networks. As a result, African farmers use 9 kilograms of fertilizer per hectare compared to 100 per hectare globally. Just as an individual farmer trying to feed himself and his family, and sell a surplus to supply national needs — all on an average 1.8 hectares — struggles to import his seeds and fertilizer, so he (most are men) also struggles to export his produce. The markets are distant and middlemen (sometimes state-controlled) who come to purchase his produce are unreliable and their prices erratic. Furthermore, fewer than 40 per cent of Africa’s farmers live within 2 kilometres of an all-season road — the lowest accessibility percentage in the world.

Land tenure is an additional critical variable. As Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto long ago explained, one of the biggest obstacles to farming productivity everywhere is the absence of anything better than usufruct rights (agreement for use and enjoyment of property by a non-owner). Very few Africans own their farms. Allocated their land by traditional chiefs, but lacking legal tenure, they cannot borrow to invest in better seeds, tools, irrigation, and other modernizations. They are caught in a low-level cash trap that largely limits productivity increases.

The percentages of African adults who are primarily agricultural producers has, for many of the same reasons, markedly declined as sub-Saharan Africa has largely grown richer per capita. Farmers are older and less well educated than other citizens; younger Africans are rejecting farming as a viable pursuit. Additionally, many African state-managed economies, such as Zambia from 1972 to 1992, subsidized urban consumers as a conscious policy. They thus deflated the prices at which state marketing boards would purchase maize (in Zambia’s case) or other commodities. So the farmers in Zambia fled to the cities, denuding the countryside of agricultural production. When the copper price on which Zambia depended for foreign exchange was high, and copper production increased, Zambia could purchase foreign-grown food and feed its citizens. But it, like Nigeria, because of oil, and other countries because of their own natural resource-dependent export regimes, lost the capacity to feed itself.

Without Chinese purchases of vast quantities of African petroleum, iron ore, chrome, cobalt, copper, coal and diamonds, many African countries would have been unable to find the foreign exchange with which to purchase food grown overseas. The actual recent costs of food imports are staggering: $3 billion to $5 billion annually for Nigeria ($2 billion of which is for rice from the United States, the rest for wheat, fish and fruit), $1.1 billion US for Kenya in 2016 to buy cooking oil from the United States, plus some chicken, wheat and sugar. If China falters and world commodity prices again slump or collapse, one after another sub-Saharan nation will be unable to feed its now-burgeoning, even exploding, population.

The natural causes of this impending crisis are obvious, and hard to defend against. But mismanagement by many African governments has also contributed to the continent’s current food crisis. The “resource curse” has led many governments to devalue agriculture and agriculturalists, to fail to meet farming needs and to enact policies that have made it extremely difficult for farmers to use their hoes well. Tanzania, for example, has failed over many decades to invest in its farming sector, instead spending preciously sparse funds on unsuccessful attempts to industrialize. Consequently, only 25 per cent of Tanzania’s 44 million arable hectares is cultivated. Food crops produced on the cultivated land contribute 25 per cent of the nation’s GDP. But less than 1 per cent of the government’s budget is spent on farmers. Zimbabwe trashed its farming sector, dominated by white Zimbabweans, for political reasons. South Africa may do the same if the existing “willing seller, willing buyer” policy is removed and confiscation of white-owned farmland becomes the norm.

Fortunately, albeit belatedly, some governments have begun to pay more attention to agriculture by increasing budgetary support, by setting aside new funds for irrigational expansion, and by investing in methods to add value to products from the soil by processing them for overseas markets. Ghana has a large new program to create jobs for young people on farms so there will be expert youthful producers to replace the generation that is now easing away from the land. They will educate young people and provide training for budding agriculturalists.

In Ghana and many other sub-Saharan African jurisdictions, various official and private schemes have brought the internet, with its pricing and forecasting capabilities, to farming pursuits. Market prices are now known and monitored, and available to farmers — no matter their remoteness. A few countries are also resuscitating extension services. Those services flourished in colonial times, helping farmers to adopt new techniques and tools, but fell into desuetude during the years of independence when most independent nations ceased funding the building of capacity among agricultural producers.

Additionally, new roads are being constructed, usually by Chinese firms, to tie farmers more closely to centres of administration and to the cities. Solar power installations are becoming more common, to help rural householders and others modernize their working and living arrangements and to give farmers a greater sense of belonging to a nation rather than to an ethnicity.

As sub-Saharan Africa continues to become more urban, so farming will become a minority livelihood. That marginalized cadre must be assisted to realize its full potential if Africa is going to attempt, once again, to feed itself. But with most parliamentarians drawn from the ranks of educated and relatively prosperous urban dwellers, it is hard to envisage an African legislature that will invest sizable funds on farmers and farming. Only when leaders appear who fully appreciate sub-Saharan Africa’s critical challenges — including overcoming obstacles to growing more of its own food — will appropriate attention be paid to food insufficiency issues and the necessary remedies introduced.

Robert I. Rotberg is the founding director of Harvard Kennedy School’s program in intrastate conflict, president emeritus of the World Peace Foundation and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts And Sciences. His latest book is The Corruption Cure. (Princeton, 2017)