Food security is the state when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations

Food security is about more than subsistence, more than what people put in their mouths — it relates to the quality of food and its ability to nourish body and soul. Food insecurity — the lack of secure access to food — is caused by interrelated conditions, mainly conflict and poverty, which are exacerbated by politics and corruption, adverse weather, crop disease, land degradation, diversion of land from food production, unstable economies and population growth.

Delivering food to the hungry is not new; it has happened since at least 330 BC when Alexander the Great’s armies gave food to conquered people. Modern resupply began around the Second World War, with airlifts to bring supplies to the Dutch (1945) and to Berlin (1948–49) when Russia blockaded the city. After the war, once the United Nations was established, international efforts delivered money for roads and railways to countries lagging technologically. Foreign aid did not address hunger.

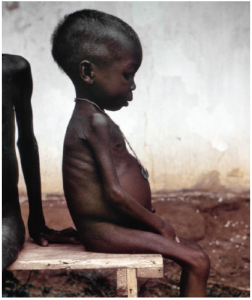

The West was horrified in 1968 by images of starving Biafran children in the news. Biafra, a secessionist state in eastern Nigeria, existed from 1967 to 1970. Its attempts to secede led to a civil war that displaced millions and killed two million civilians. When the UN failed to provide aid, convinced by Nigeria that it would be illegal, an improvised coalition of church groups and non-governmental organizations planned the Biafran airlift. It was a pivotal event in the awareness of, and response to, hunger in that it imprinted famine onto the global conciousness.

In 1974, the FAO hosted the first Rome World Food Conference. Its biggest concerns were the International Fund for Agricultural Development, world food security and an international framework for implementing the conference’s recommendations. The conference declared “the rights of every human being to be free from hunger and malnutrition.” Henry Kissinger, U.S. secretary of state, opened the conference saying famine was once considered part of the normal cycle of existence, but with our new global consciousness, we “must proclaim a bold objective — that within a decade, no child will go to bed hungry.”

Today, the international hopes to achieve global food security and improve nutrition by 2030. The FAO notes that reaching this target “will be challenging.”

Causes: conflict and poverty

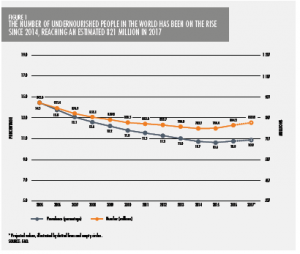

Although enough food is produced to feed the world’s population, 821 million people go hungry around the world, down from 900 million in 2000, but up from 777 million in 2015, putting the goal to eradicate hunger at risk. The increase is due to the greater number of conflicts in the world, compounded by increasing climate events. The majority of hungry people live in developing countries, where 14.3 per cent of the population is undernourished, mostly the result of poverty, which is largely caused by conflict. The UN lists the least-developed countries as Afghanistan, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Liberia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen — the countries also most affected by conflict. The countries the UN currently identifies as most at risk of food insecurity becoming famine are Nigeria, Somalia and Yemen.

Conflict creates poverty; its biggest victims are the smallest. The effects of poverty can devastate childhood development and the effects are permanent. Studies of children under five across four continents by the World Health Organization, Emory University and the International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research have shown that insufficient nutrition causes stunted physical development and diarrheal diseases and contributes to intellectual deficits and mortality. The UN reports that more than 150 million children are stunted, with 39 per cent in Africa and 55 per cent in Asia.

In Yemen, approximately 17 million people — 60 per cent of the population — face severe food insecurity. Chronic undernutrition and chronic acute undernutrition in children are significant. The health-care system has collapsed; 60 per cent of medical facilities are not fully functional, unable to provide even basic services. Additionally, a cholera outbreak began in September 2016 and countries affected by food insecurity also face Ebola, influenza, meningitis, Rift Valley fever and yellow fever.

The effects of poverty and food insecurity do not stop at the individual. Increasing and volatile food prices have led to political instability and civil unrest from the Middle East to the Caribbean. From 2007 to 2011, unstable global food prices caused widespread food insecurity. In 2010-11, they played a role in the Arab Spring, with protests in countries around the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz, through which passes more than 20 per cent of the world’s crude and petroleum exports. Oppressive government responses turned peaceful protests violent, leading to volatility in energy markets. The resulting instability strained relations between Egypt and Israel and required NATO intervention in Libya.

In South America, Colombia’s five decades of conflict left 6 million people — 14 per cent of the population — internally displaced by armed groups seizing rural territories and controlling natural resources and land. Much of this activity has been connected to drug trafficking, with land use diverted from staple food crops and with transport routes controlled by cartels.

Clearly, stability in agriculture sectors and food sources matters to national security. In developing countries, 50 to 90 per cent of the population is engaged in agriculture as the main source of income and employment and up to 95 per cent of the farming population comprises small farmers. In conflict-affected countries, 56 per cent of the population, on average, lives in rural areas with subsistence agriculture the main source of food.

Agriculture is at the heart of food security; conflict affects it profoundly in every aspect from field to consumer. In pre-conflict Iraq, roughly 30 per cent of the country’s wheat and 40 per cent of its barley, crops now also affected by climate change, were produced in the districts of Salah al-Dinh and Ninewa. In February 2016, the FAO determined that conflict damaged or destroyed 70–80 per cent of wheat and barley crops in Salah al-Dinh. In Ninewa, 32-68 per cent of wheat fields and 43-57 per cent of barley fields were compromised or destroyed.

Afghanistan, with a fragmented and polarized population, has a long history of conflict reaching back to the 4th Century BC. Besides civil war, it has been the battleground for external powers and has warred with Britain, Russia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and Canada, spawning the Taliban and al-Qaeda. The current conflict started in 1999.

Four of five Afghans rely on agriculture for food and income but, per capita, land ownership by farmers is inadequate to feed their families. Agriculture and food distribution have been impacted by opium cultivation, extortion, corruption, drought and national and local power brokers manipulating operations. Drought affects two-thirds of the country, with the potential for extreme food shortages in 2018 to affect up to 2 million people, adding to the nearly 2 million who have already fled their homes because of decades of war.

Climate change and nature

Natural conditions compound the consequences of conflict on agriculture. While the UN urges co-ordinated global action to address climate change and thereby mitigate its effects on agricultural success, offsetting it is a long-term proposition that will only be hampered by conflict. Climate change compounds conflict when arable land is lost to drought or floods, resulting in fighting over land and water. The FAO reports that up to 40 per cent of civil wars over the past 60 years have been associated with natural resources and 48 per cent since 2000 have been in Africa where rural land access is essential to livelihoods and where 27 of 30 conflicts have involved land issues.

Solutions: Give peace a chance

Ensuring food security is a moral imperative and humanitarian obligation. But delivering food will not achieve zero hunger; it is temporary support but, over decades, may create dependence on aid.

Because food insecurity is prevalent in developing countries, addressing it has followed the approaches of development projects. Many show lasting results that stimulate local economies and reduce aid dependency. Some projects fail because they are based on creating a version of a country with no relation to its actuality. Charged with spending their budgets, agencies create a picture of what they know how to solve. Ultimately, development expands state power, but not always access to food and resources.

For example, in Lesotho in the 1970s, attempts to mitigate poverty through employment in South African mines were largely unsuccessful because development agencies did not understand the male social system. Miners purchased cattle with their wages, boosting their prestige in their communities, instead of food and goods their families needed. The livestock could not be sold or slaughtered, but became a retirement fund, available for the future when the man could no longer work. While the men attained some wealth, their efforts did not immediately improve their families’ food security. Attempts to modernize the “livestock sector” by monetizing grazing lands and improving livestock failed when the people resisted Western-style practices. In the end, when aid workers left, their budgets expended, the families continued marginal farming and waiting for mine wages. The only change was the expanded presence of the government that had used the project for political promotion.

A recommendation for increasing income to improve food security for smallholder farmers is cash cropping — producing specific crops for sale, not household consumption. A farm family that had once raised several food crops and livestock to feed its members and sell any surplus would switch its production to a single crop, such as coffee, with no food grown for consumption, but an income for purchasing commodities. However, if that income is insufficient to feed the family, particularly in a volatile market, they must seek employment, sometimes at a distance or where they earn only a meagre living.

A study in rural Ghana found “limited evidence documenting relationships between [cash] crops and the food security of households cultivating them” (Food Security, August 2014). The study measured food availability (months when households reported adequate food), access to food, and food utilization (diversity of household diet and evidence of children’s nutrition.) The study found the relationship between food security and a household’s effort to produce the cash crop was significantly negative, suggesting we cannot assume positive relationships in cash cropping. The underlying causes of Ghana’s cash crop failure included increases in food prices and competition for land use.

Alternatively, a 2014 study by Wageningen University in the Netherlands indicated cash crops are an important strategy for food security of farm households in developing countries because such households can sell their surplus to generate income to improve access to food. Cash crops, such as cocoa or coffee, provide income and employment within the rural economy and generate capital for innovation and improvements. However, as the study notes, mono-cropping requires managing soil degradation and price volatility, risks that may be addressed by farming co-operatives, commodity exchanges or crop rotation to cope with crop failure, price drops and lost market access.

On the plantation scale, well-managed cash cropping can be very successful, although it may not support as many individual farmers on the same amount of land. However, mono-cropping is associated with limited production of other crops, including food, and increased prevalence of harmful insects and pathogens. Irrigation and over-pumping water to support mono-cropping have resulted in falling water reserves in many countries, including China, the U.S. and India. Reliance on a single crop created Ireland’s famine of 1845-1849 when successive crops were devastated by blight. The rural poor in particular depended on the potato and approximately 1 million people died of starvation or famine-related diseases and nearly 2 million emigrated.

Between 2014 and 2016, the failure of cash crops in Karnataka, an Indian state, was responsible for nearly 1,500 farmers committing suicide. They had been growing tobacco, cotton or sugarcane; the crops had a high return in successful years, but they required large investment. Crop failures can mean bankruptcy for farmers without other crops or occupations.

Although food scarcity is not due to overpopulation, reducing population growth will help, especially women and children in developing countries. Even though fertility rates have declined worldwide, at the current rate of growth, the world’s population will be 9.7 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100. Nigeria has the most rapidly growing population; it is projected to exceed the population of the U.S. by 2050. Some organizations suggest the solution is increasing global production of food crop calories by 60 per cent, but note that the lack of arable land means the increase will have to come from higher yields. This means using more water and fertilizer or developing innovative farming methods. But with so much conflict in areas where food is required, as well as extreme climate events in the same areas, it also raises questions of exactly where extra food can be grown and if grown afar, how to provide it without creating aid dependency.

With population growth concentrated in the poorest countries, combatting poverty, hunger and malnutrition and expanding education and health systems can begin by promoting family planning and birth control, but it requires changing the thinking in such countries.

In an agrarian society, children are a source of labour; with the decline of householder farms, that situation has changed, at least in the interim. The hope that at least one child in the family will get an education and then a city job to support the family will hardly be realized if children starve or are undernourished. Having fewer children, besides fewer mouths to feed, means less maternal mortality and better health for all.

The UN has long noted that improving women’s condition benefits socio-economic development. Providing education about sexual and reproductive health is crucial in developing countries, particularly given the statistic from the WHO that “214 million women of reproductive age in developing regions who want to avoid pregnancy are not using a modern contraceptive method.” In Malawi, the government’s 2009 commitment to stop population growth has led to greater use of modern contraceptives, fewer unsafe abortions and more health providers.

Overall, the biggest obstacle to food security is conflict. In May 2018, in a historic vote, the UN Security Council, for the first time, recognized that armed conflict and violence directly impact food security and condemned starving civilians as a method of warfare, calling on all engaged in armed conflict to comply with international laws to protect civilians. The FAO went on to develop a new framework aimed at keeping farms out of conflict, noting that conflict-caused agricultural losses outstrip development assistance and roughly 87 per cent of “people living in extreme poverty also live in environmentally vulnerable and fragile countries.” As the World Food Program says, “We can’t end hunger if we don’t end conflict.”

War between nations has declined since the Second World War. Mainly it is internal conflict that’s killing and starving people. Civil wars begin at the same rate today as they have for 60 years, starting each year in up to two per cent of countries. Involvement of outside countries is high, with four countries becoming most involved, supporting either government or rebel groups. Since 1989, Britain and France have sent troops to five conflicts, the U.S. to three and Russia to two.

Civil wars are messy and they end that way. In a civil war, each side feels it must continue fighting or be killed. In general, military victories provide more stable outcomes than settlements, but military victories destroy state institutions required for long-term stability. Negotiated compromises can seem unbearable to those who want victory and sometimes the only solution is state break-up. Ultimately, ending civil war requires will and leadership.

Looking at the history of conflict in the world, one would think that fighting is part of the human condition, that governments engaged in long conflicts simply cannot reconcile themselves to peace. If that is the case, achieving zero hunger on a global scale is impossible.

In June 2018, Ethiopia announced its plans to implement a peace agreement with Eritrea that had lain dormant since 2000. Eritrea had gained independence from Ethiopia in 1991 after three decades of war, but a territorial dispute broke out in 1998. Acknowledging that both sides have suffered horribly, Ethiopia’s reformist government announced that change must occur for the common good and handed disputed areas to Eritrea.

Whether this peace restores stability and brings people food security remains to be seen, and there is much to be worked out, but it is, even temporarily, a ray of hope for hungry people.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky is an Alberta writer and researcher and the former associate editor of The Canadian Encyclopedia.