Debt is a powerful force, with total global government debt exceeding US$65 trillion, up from $37 trillion a decade earlier. Wolfgang Depner examines global debt and gives shout-outs to the world’s best financial bosses.

It was a small but symbolic occasion. For the first time in 20 years, Germany’s debt counter reversed direction in January 2018. With every passing second, Germany’s total public debt of US$2.37 trillion shrinks by $572. At this rate, it will take Germany 800 years to pay back its current debt. Whether Germany or any other country still exists in the early 29th Century is another question.

This debt reversal invites several points. First and foremost, it draws attention to the massive mountain of debt that confronts governments around the world. At the end of 2018, total government debt exceeded $65 trillion (all numbers expressed in U.S. dollars) — up from $37 trillion a decade earlier. The U.S. government alone owed US$21.9 trillion in early 2019, and the current trendline of U.S. debt has known only one direction — up.

Historical and contemporary reasons for this reality are many, but include tax cuts, social entitlements, stimulus spending, military spending and the debt itself.

As the The New York Times reports, the U.S. could soon pay more in interest on its debt than it spends on military and social programs combined. This point speaks to one of the fundamental dangers of debt. It starves socially productive causes of scarce resources that benefit the public.

Money that goes towards paying off debt won’t go towards building roads, schools, hospitals and scientific research, and limits the financial flexibilities of government when faced with genuine emergencies, such as a war or an economic depression, which require counter-cyclical stimulus.

Debts also raise interest rates, causing inflation that discourages private investment and weakens consumer purchasing power.

Finally, debt is also a question of inter-generational equality. Rising debt levels in the present will leave future generations with unappetizing choices: They can either raise taxes, cut spending, or both, to deal with the burdens created by past generations.

Finally, debt is also a question of inter-generational equality. Rising debt levels in the present will leave future generations with unappetizing choices: They can either raise taxes, cut spending, or both, to deal with the burdens created by past generations.

Canadians of a certain age will likely remember the difficult choices that Canada faced in the 1990s when the federal Liberals, under prime minister Jean Chrétien and finance minister Paul Martin, cut social programs across the board to undo the damage caused by previous Liberal and Tory governments.

Or more drastically, consider the effects that the sovereign debt crisis of 2011 had on societies across Europe, especially Greece, but including Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Cyprus. Briefly, these countries were unable to service their public debts, forcing them to accept financial help from the international community in exchange for policy reforms, whose social legacies will remain for generations.

By that measure, German officials have reasons to crow about their financial management skills. But smugness would be misguided.

Debt is not just an economic variable, but also a political object. No small number of economists, including French economist Thomas Piketty, have argued that an excessive focus on debt is detrimental to the quality of governance.

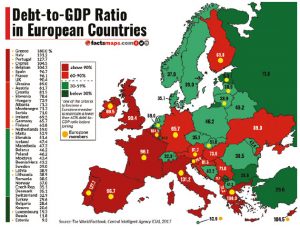

Within this context, Piketty has been especially critical of Germany in its role as an advocate for austerity throughout the European Union generally and the Eurozone specifically. (Under the Maastricht Treaty, signatories must limit their debt-to-gross-domestic-product (GDP) ratio to 60 per cent and their annual deficit must be no greater than 3 per cent of GDP).

This critique reached a crescendo in the mid-2010s when Germany insisted on — some say, imposed — harsh austerity measures as Greece and other Eurozone members struggled with their debts in the aftermath of the great financial crisis — a crisis initially caused by private banks rather than governments.

Germany, in this reading, was causing unnecessary harm to millions, while undermining solidarity in the European Union, ultimately to its own detriment. Critics also pointed out that Germany itself had been the benefactor of significant debt relief in the respective aftermaths of both world wars in the first half of the 20th Century. Germans themselves might also concede that their government’s eagerness to cut debt has left behind a crumbling social and physical infrastructure.

(On the other hand, Germany’s experience with hyperinflation in the early 1920s, caused by debt related to the First World War and reparation payments, continues to scare contemporary generations.)

Finally, debt is also a moral category with religious overtones. The German word for debt — schuld — can also translate as guilt or transgression. Accruing debt thus appears as a sinful act. Readers of Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and Capitalism will also be familiar with the argument that frugality is close to godliness in some corners of the world.

Others may disagree, but debt has been an undeniable part of human history, as David Graeber shows in Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

To paraphrase Karl Marx, Graeber’s tour-de-force leaves the impression that the “history of all hitherto existing society is the history of debt.”

Or as François Rabelais says through his character, Panurge, debt “is the whole Cement whereby the Race of Mankind is kept together; yea, of such Virtue and Efficiency that, I say, the whole progeny of Adam would very suddenly perish without it.”

Or, put in a less stilted manner, civilization itself might collapse without it.

No G7 countries made Top 10

In light of these complexities, we have decided to highlight the 10 countries that have shown the greatest skills in managing their public finances as measured by their debt-to-GDP ratio.

Specifically, we have chosen to highlight developed countries as identified by their membership in the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with debt-to-GDP ratios below 60 per cent, the prudent debt limit for developed countries that appears in the literature and is used by the European Union. (All figures are from 2017, as recorded by the OECD, to ensure comparability at a definitive point of time.)

So what does this list reveal? It suggests that the most frugal nations fall into two broad categories: small, technologically advanced countries with specialized economies and efficient institutions, and up-and-comers with emerging social systems. Notably, none of the world’s leading economies, as represented by the G7, made the list, although Germany currently hovers just above the 60 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio as of this writing.

1. Estonia: 12.6 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio

Estonians, 30 years ago, joined Latvians and Lithuanians in a human chain that connected their respective capitals of Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius. The occasion of their protest was the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, whose secret protocol consigned the Baltics to the Soviet Union.

This “Baltic way“ contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and catapulted Estonia onto an exceptional path of economic growth during which it has not only defied expectations, but also defined standards. One such standard is the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio among OECD countries, the outcome of several decisions.

Successive governments, starting with the radical reform administration of Mart Laar, have made the Estonian government less corrupt and more efficient.

Estonia has risen to 21st spot in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (2017) over the years, approaching the standards of the Scandinavian neighbours from which it draws inspiration. Businesses can set up shop with speed and bureaucrats always look for efficiencies.

Estonians can already file their taxes, order various public documents and even vote online, through a system that allows citizens and residents to identify themselves online and supply legally binding digital signatures.

The Estonian cabinet — already working paperless for years — has since announced additional measures to completely digitize government in all but a few areas. According to The New Yorker, digitization reportedly saves the Estonian state two per cent of its GDP per year in salaries and expense — about the same amount that it pays for its military. This has led to the joke that the country gets its national security for free.

Its status as “most advanced digital society in the world,” according to WIRED magazine, not only saves Estonia money, but also stokes a digital economy that fills public coffers by drawing global talent and money. Tallinn has emerged as a hub for high-tech industries, which account for 15 per cent of GDP, and if you have ever used Skype to connect with business partners and family members around the world, you can thank, among others, a group of Estonian programmers.

An e-residency program has also attracted investors who want to take advantage of Estonia’s flat-tax system, efficient administration and membership in the European Union (EU) and Eurozone — clubs Estonia increasingly shapes through the New Hanseatic League, a Dutch-led coalition of northern EU members calling for more frugal, effective governance.

E-residents of Estonia include not only several venture capitalists, but also His Holiness Pope Francis and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose government has been studying Estonia as a model for digital governance.

Estonian President Kersti Kaljulaid told The New York Times that Estonia is the first digital society in the world to have its own state. Her assessment is not far off; in many ways, Estonia is the ultimate startup.

When Estonia regained independence after decades of foreign domination, its backwardness offered a blessing in disguise. The country could start with the latest technology, which it married with an entrepreneurial spirit and public investments in the educational system, which is among the best in the world.

What has emerged is a trim but free and efficient society, largely unencumbered by the expensive legacies that burden other countries. Whether others can copy Estonia — a country of 1.3 million people — remains unclear. But it shows that countries can overtake without first catching up.

2. Luxembourg: 27.74 per cent

This founding member of the European Union (1957) and the Eurozone (1999) is Europe’s version of Singapore. Despite its small population (605,000), area (it’s a little smaller than half of Prince Edward Island, or 2,586 square kilometres,) and absence of natural resources, Luxembourg ranks as the fifth-wealthiest place on the planet, with a per capita income of $105,100, according to the CIA World Factbook. Luxembourg, like Singapore, has leveraged a strategic location with efficient institutions to become a global hub for financial services, logistics — and increasingly — technology. Its multilingual, multinational workforce lends it an international flair.

Measures of this success include not only Luxembourg’s high per capita GDP, but also its positive trade balance and low level of public debt, at 27.74 per cent of GDP in 2016, the lowest rate in the region. Compare: The OECD shows Germany, Belgium and France with respective rates of 71.5, 121.9 and 124.2 in 2017. While not a direct neighbour, the nearby Netherlands records a rate of 70 per cent. So some, if not the most important members of the EU and the Eurozone, do not come across as models of fiscal discipline.

It is difficult to draw like-to-like comparisons in light of Luxembourg’s size. But its broader influence on fiscal policy should not be underestimated. Luxembourg hosts the European stability mechanism, responsible for the euro’s permanent rescue fund and the height of the Greek debt crisis during the summer of 2015 coincided with the country’s presidency of the Council of the European Union.

This episode thrust two politicians from Luxembourg into the maelstrom — Jean Asselborn, Luxembourg’s minister of foreign and European affairs, and Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, the cabinet-like executive of the European Union.

Juncker, especially, found himself torn. Critics from the left, such as Piketty, accused him of being too harsh towards Greece, while fellow conservative Wolfgang Schäuble, then Germany’s finance minister, accused Juncker of not being harsh enough.

Juncker’s agenda of financial support in exchange for reforms eventually prevailed, but history’s judgment of his role in the Greek debt crisis remains to be seen.

As European affairs correspondent Caroline de Gruyter argues, Luxembourg is the bellwether of Europe, whose policies reflect larger European tensions.

Luxembourg fully supports European integration, but has also shown a lack of solidarity by exploiting — even encouraging — questionable business practices at the expense of its tax-deprived neighbours and allies, as the 2014 LuxLeaks scandal exemplifies.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists revealed in 2014 how the government of Luxembourg was sheltering taxes for 340 companies, with IKEA, Amazon, Deutsche Bank and Canada’s Yamana Gold, Fairfax Financial Holdings and Brookfield Asset Management among them. One of the central figures in this scandal was none other than Juncker himself, whose time as Luxembourg’s prime minister (1995-2013) and finance minister (1989-2009) coincided with the worst practices. Having survived a vote of censure from the European Parliament, he was also, strangely, put in charge of overseeing reform of Luxembourg’s tax-dodge policies. Subsequent leaks have since revealed that Juncker’s commitment to tax fairness before and after becoming president of the European Commission has been shaky at best.

Like the rest of Europe, Luxembourg faces what de Gruyter calls “enormous” future pension liabilities because of its aging yet well-paid civil servants, whose salaries are on par with the private sector.

This ticking time bomb, coupled with competition from other niche countries, and the populist threat of European disintegration, could well rob Luxembourg of its exemplary status.

3. Chile: 29.65 per cent

As the first Latin American country to join the OECD (2010), Chile is often held up as a model, showing the benefits of trade, deregulation and private-market solutions during its ascension into the club of developed countries, ahead of Latin American powerhouses Argentina and Brazil. This case rests on the growth that Chile experienced after the end of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship in 1988.

Between 2003 and 2013, real growth averaged almost 5 per cent. Others may point to the commodity boom of the early 2000s, during which the price of copper surged. (Chile is the world’s largest producer of copper. It accounts for 43 per cent of its exports and 20 per cent of government revenue).

Chile also pursued broader social reforms that fought corruption, reduced tax evasion and protected consumers during the two decades that followed Pinochet’s departure.

“The tiger of Latin America,” as The Economist called it, is now looking to regain its bounce after a period of stagnation that exposed Chile’s dependence on copper, but also deeper social tensions over the right economic approach. Perhaps the most obvious was the Chilean Winter, during which university students demanded relief from crippling debts caused by expensive for-profit universities.

These protests — which started in 2011 and lasted for two years — also appeared as a critique of the neo-liberal policies promoted by Sebastián Piñera, the country’s first right-wing president since Pinochet.

Piñera’s socialist predecessor and eventual successor, Michele Bachelet, seized on this sentiment to regain office in 2014. But her turn towards the left scared business, and Piñera now finds himself back in office, having to navigate a divided society at home and an uncertain economic climate abroad, with copper prices now pointing downwards.

Chile’s debt-to-GDP curve neatly captures these general trendlines. In 2003, its rate was 23.9. By 2007, it had fallen to 11.3 per cent. It rose as Bachelet’s government pumped money into the economy to counter the effects of the Great Recession.

It has been rising ever since — through Piñera’s first term and Bachelet’s second term, with the trendline pointing up during the early phases of Piñera’s second term, reaching 29.65 per cent in 2017.

Chile’s debt remains low compared to its neighbours, but economists fear it might find itself in a middle-income trap, unable to expand economic growth after reaching a certain level, while faced with growing expectations from its expanding middle class.

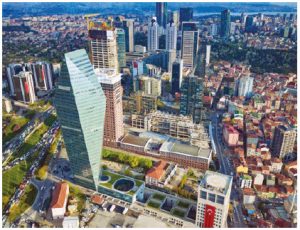

4. Turkey: 35.17 per cent

Future historians of Turkey who are studying the era of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his AKP will likely distinguish between two broad periods: the period before the failed coup of July 15, 2016 and the period after.

The start of the first period in 2003 — when he took office as prime minister — may well go down as the start of a golden era in Turkey’s economic history. During this prosperous period, the country recovered from a banking crisis at the start of the decade that had required an intervention from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The country experienced sustained economic growth, with GDP growing more than 6 per cent annually until 2008.

Exports, especially into the neighbouring European Union, rose, inflation fell and the public debt melted away. Consider the numbers: In 2001, the IMF recorded Turkey’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 77.94. By 2008, it had fallen to 39.98 per cent. In short, it nearly halved in six years.

While GDP plunged and debt rose in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession (2009), growth soon recovered. Debt levels once again dropped. In 2010, Turkey recorded a debt-to-GDP ratio of 49.2 per cent, according to the OECD. By 2015, it had to fallen to 32.8 per cent, in line with the IMF, which pegged the debt-to-GDP ratio at 32.93 per cent in 2015.

Accordingly, Turkey’s status rose, especially among its Arab neighbours, who considered its mixture of democratic governance, capitalism and mildly Islamic policies a model worthy of emulation during the Arab Spring.

Turkey under Erdogan has since become a synonym for political instability and authoritarianism, with an economy that is reeling. Galloping inflation, rising trade deficits and a slumping raised global fears about the stability of Turkey, a geo-strategic hinge between the Western world, Russia and the Middle East.

The problems besieging Turkey’s economic model of consumption and

construction did not start with the amateurish military putsch against Erdogan, but his response to it deepened them.

Erdogan’s refurbishing of Turkey into a presidential system tailored to his needs has delayed economic reforms, the need for which predate the coup. Mass arrests of political opponents and property confiscations have scared off investors, who are leery of losing their investments at the hands of an unpredictable political system with a waning commitment towards the rule of law and democratic rule.

Tourists — an important source of foreign revenue — have stayed away on general fears of further instability and reports that the regime has arrested foreigners for making anti-Erdogan comments.

This institutional paranoia is personal. Erdogan sees enemies plotting against him everywhere, and his obsession with defeating them has not only caused diplomatic rows with allies, but also blinded him to the causes of Turkey’s problems. Contrary to his claims, Turkey’s economic problems were not some Western plot. But the institutions that could have told him to act otherwise refused to resist the Bully of the Bosporus, whose grasp of economics revealed itself to be questionable during the crisis. True, it could have been worse, but it has been bad enough, as Turkey officially experienced a recession last year.

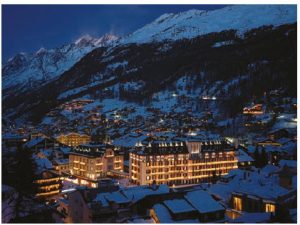

5. Switzerland: 42.46 per cent

Leave it to the supposedly staid Swiss to have started a revolution in public financial management.

Between 1990 and 1998, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 31 per cent to 54 per cent. As Stephan Danninger wrote for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2002, this ratio was “not excessive” by international comparison, but nonetheless remarkable, because several European countries, including the Netherlands and Denmark, had taken steps to reduce their respective ratios.

The reasons Danninger cites for Switzerland’s rising debt included economic stagnation because of low productivity growth and high unemployment (by Swiss standards). Perhaps the central piece of Swiss reforms during this period was the introduction of a debt brake through a constitutional amendment approved by 85 per cent of voters in a national referendum in 2001 and effective since 2003.

Switzerland’s Schuldenbremse [debt brake] links expenditures with revenues over the course of an economic cycle to ensure that expenditures do not exceed revenues. Its rules allow the federal government to run deficits during recessions, while generating surpluses during booms. It also contains an escape hatch to deal with extraordinary circumstances.

So has the debt brake worked? On the surface, yes. While other countries have seen their debt levels rise, Switzerland has reduced its outstanding obligations, granting itself more fiscal room and lower interest payments.

Consider the following: In 2003, Switzerland’s debt-to-GDP ratio hovered around 59 per cent. Between 2007 and 2016, it ranged between 45.6 and 42.46 per cent. By comparison, the average debt-to-GDP ratio within the OECD exceeded 80 per cent in 2015. More fundamentally, the debt brake has changed the budgetary process. It discourages ministers from spending surpluses during good times, forcing them to prioritize, because the expenditure ceiling drops during booms.

This Swiss self-restraint not only reflects the general loathing of debt in German-speaking countries, it has also become a source of Helvetic pride as Swiss officials tout their debt brake as a model for others to follow.

It certainly inspired Germany, Europe’s largest economy, to introduce its own debt brake in 2009. Germany has since touted this attitude to the rest of Europe as an apostle for austerity, much to the chagrin of other EU members and notable economists such as Piketty.

But if the statistics tell one story about the Swiss debt brake, it is also important to acknowledge that it exists in a specific context. Switzerland, one of the world’s most advanced economies, already possessed relatively low debt levels by international standards before introducing its debt brake, and some economists have argued that the Swiss federal government is actually not spending enough.

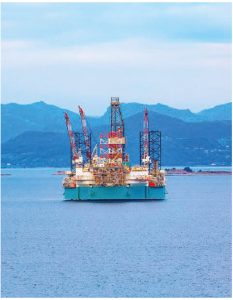

6. Norway: 42.8 per cent

What if Venezuela had acted like Norway? Would the country with the fifth-largest oil reserves in the world have avoided its current economic catastrophe if it had placed portions of its oil earnings in a sovereign wealth fund?

While hypothetical questions are of no assistance in the current situation, they draw attention to the dangers of managing newfound wealth — dangers Norway has been able to circumnavigate with careful planning and growing confidence.

Norwegians are not just among the happiest and healthiest people on the planet. They are also among the wealthiest thanks to their government’s decision in 1996 to place revenues from the country’s petroleum sector, which accounts for about 9 per cent of all jobs, 12 per cent of GDP, 13 per cent of revenues and 37 per cent of exports, in a sovereign wealth fund.

Norwegians could have easily chosen to indulge themselves. But as many countries can confirm, oil wealth is not only fleeting, but also distorting. It encourages expensive imports, diminishes long-term productivity by raising local wages, and much of it often ends up in the hands of a few, corrupting politics along the way.

Norway, however, chose a different path. It showed, in the words of current NATO general-secretary Jens Stoltenberg, the “political courage” to save most of its oil money. The Government Pension Fund of Norway has since become, in the words of Forbes, “the world’s biggest state piggy bank,” whose asset value surpassed $1 trillion in September 2017.

To appreciate the size of the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, consider the following. Valued at around $1.1 trillion, it is worth more than twice the Norwegian economy, and would net every Norwegian man, woman and child around $200,000.

By virtue of the fund, 5.3 million Norwegians hold about 1.5 per cent of all global stocks, an amazing figure considering that the world’s second-largest fund is in the possession of China, with a population of about 1.4 billion people.

This reality gives Norwegians considerable sway on global economics. If they do not like the investment decisions of their government for various ethical or environmental reasons, industries and companies around the world will feel their influence.

So what accounts for the success of the fund? First, the Norwegian petroleum industry is heavily regulated and taxed, with private oil companies paying a tax rate of 78 per cent. Second, the fund is transparent and subject to parliamentary control. Third, the Norwegian state continues to show restraint in the face of political pressure to spend more, leaving Norway with perhaps the best of all worlds: relatively low debt, a functioning social system and a healthy financial cushion for the future, once its current oil supplies have dried up.

7. Czech Republic: 44 per cent

7. Czech Republic: 44 per cent

Three decades after the end of the Cold War and 15 years after the expansion of the European Union into Eastern Europe, post-Communist countries continue to catch up to their Western neighbours and former political rivals.

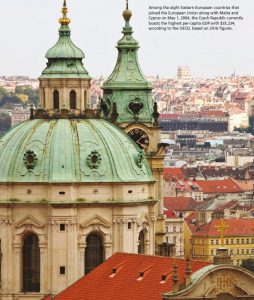

Consider the Czech Republic. Among the eight Eastern European countries that joined the European Union along with Malta and Cyprus on May 1, 2004, the Czech Republic currently boasts the highest per-capita GDP with $35,234, according to the OECD, based on 2016 figures. Only Malta tops all members who joined the EU in 2004 with a per-capita GDP of $38,308. While still behind the EU’s average per capita GDP of $40,210, the Czech Republic has undeniably benefited from the end of the Cold War and European integration as an important location for the European automobile industry.

One measure of the country’s success is its relatively low debt-to-GDP ratio, which currently sits at 44 per cent, down from 58 per cent in 2013. This said, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 18.2 per cent in 1996, and 32.9 per cent in 2004, when the Czech Republic joined the EU.

In short, the Czech Republic has been improving its public finances, but only after seeing debt levels rise, with the proviso that rates have remained manageable when compared to the rest of the OECD. (Reasons for the rise in debt during the late 1990s, early 2000s included, among others, currency depreciation, sluggish growth and new accounting measures that identified previously hidden debt).

However, Czech officials are eager to note that international credit agencies show confidence in the country as an investment location with some investors calling the Czech Republic the Switzerland of Eastern Europe. But, as with the rest of Europe, the Czech Republic faces a demographic time bomb. As economists Nicholas Eberstadt and Hans Groth note, “inexorable demographic forces” are transforming OECD countries into a “grey zone” where fewer young people will have to support more older people.

“Demographic projections today depict a radically different Western world 20 years hence,” they say, “one with stagnating populations, shrinking workforces, steadily increasing pension-age populations and ballooning implicit social spending commitments.”

The economic effects of these “impending demographic changes” include slower economic growth and higher public debt burdens.

While the Czech Republic is not aging as quickly as Western neighbours, such as Germany, it (like other Eastern European countries) is facing the same trend lines.

8. Latvia: 47.3 per cent

Why would anyone adopt the euro? That was the question facing Latvia when it applied for membership in the Eurozone in spring 2013. Two years after the start of the sovereign debt crisis, the financial state of several Eurozone members was destroying global confidence in the common currency as the crisis hurtled towards its climax in 2015, when Greece nearly left the common currency. Why would anyone jump onboard a sinking ship, many wondered.

Latvians, too, had their doubts. Almost 60 per cent of them questioned why their country would exchange its currency — the lat — for the euro, some two decades after having restored it as a symbol of Latvia’s regained independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

This reluctance reflected Latvia’s recent economic history. Between 2007 and 2009, it suffered the worst recession in Europe, as GDP dropped 24 per cent. The Latvian government responded by combining financial support from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) worth $10.1 billion with drastic austerity measures. Fully 30 per cent of civil servants lost their jobs and those who kept theirs earned 40 per cent less. New taxes appeared and old ones rose. These measures not only rapidly increased poverty among Latvians, but also encouraged tens of thousands of them to leave, no small figure for a country of a little more than two million.

But this shock therapy worked insofar that GDP recovered. By 2012, the Latvian economy grew 5.6 per cent, the fastest in Europe. But it also made Latvians who, like their Baltic neighbours, see themselves as austere northern Europeans, weary of committing their financial futures to outsiders, especially spendthrift politicians in southern Europe.

Joining the Eurozone was not a question of fulfilling its technical criteria. While Latvian debt rose to 53.2 per cent of GDP in 2010 from 12.8 per cent in 2007 because of the Great Recession, the debt-to-GDP ratio has remained well below the 60-per- cent criterion.

It was rather a question of whether Latvians were ready to wear a financial straitjacket with all its perks, but also responsibilities. In the end, arguments in favour of the euro rested on Latvia’s pre-existing financial ties with euro countries, and geo-strategic concerns in the face of the Russian threat. As one Latvian

entrepreneur summed it up at the time, “better the euro than the ruble.”

Five years after officially joining, the government has used Latvia’s Eurozone membership to raise the country’s international influence, and Latvians, while still stashing away lats, have come around, with 83 per cent of those surveyed supporting the euro.

9. Lithuania: 47.8 per cent

The last of the three Baltic countries to adopt the euro in 2015 after Estonia (2011) and Latvia (2014), Lithuania is also the last country to have joined the OECD (2018).

But it would be a mistake to think of Lithuania as a laggard. Between 2006 and 2017, it recorded the highest economic growth in the OECD with an average annual GDP increase of just less than 4 per cent. Not surprisingly, it has received praise for its economic growth generally and financial management specifically. “The financial system is resilient, and fiscal positions stabilized after a long period of deficits and rising debt,” the OECD wrote in its June 2018 survey of Lithuania.

Mixed with this praise is the acknowledgement that Lithuania has seen its debt levels rise, from 17.1 per cent of GDP in 2008 to a recent height of 54 per cent in 2015.

It is now trending downward, but other more pressing issues loom.They include the need to raise productivity and address demographic challenges.

In terms of productivity, Lithuania remains 30 per cent below the OECD average. Lithuania — like Latvia — is also losing population. In 1990, its population numbered 3.69 million. In early 2019, it numbered 2.86 million because of declining births and out-migration, mostly of the young. The OECD calls this trend “disquieting” because it deprives the country of its most dynamic people, while causing skill shortages.

Ultimately, developments such as those likely pose more significant threats to the long-term sustainability of any society than any specific debt number.

10. Denmark: 50 per cent

The Nordic model remains an object of uncritical admiration and misleading vilification. Its supporters on the left downplay its transferability to larger jurisdictions. Promises of Scandinavian social policies by progressive politicians in the United States may be idealistic, but ultimately illusory. They would not only meet significant institutional barriers, but also cultural opposition. Conservative voices have also made the point that mimicking the Nordic model in the United States might not only mean higher taxes for the very rich, but also parts of the middle class.

Critics of the Nordic model, meanwhile, overstate its tax burden and detrimental effects on public finances. Yes, taxes in Scandinavian countries such as Denmark are higher than the OECD average, but they get something in return. By way of comparison, single workers in Denmark faced an average net tax rate of 35.8 per cent, while the OECD average was 25.5 per cent. The rate for married workers with two children was 25.3 per cent in Denmark, 14 per cent for the OECD. Danish workers, in other words, get to keep less of their earnings.

They also pay higher taxes on everything from cars to coffee. But they get more in return — be it through specific social policies or the general peace of mind that they are living in a society where income redistribution creates social cohesion and a more level playing field, not unlike what American political philosopher John Rawls had envisioned.

They also pay higher taxes on everything from cars to coffee. But they get more in return — be it through specific social policies or the general peace of mind that they are living in a society where income redistribution creates social cohesion and a more level playing field, not unlike what American political philosopher John Rawls had envisioned.

More important, the presence of Norway and Denmark on this list undermines the theory that Scandinavian countries are spendthrifts. (Sweden’s debt-to-GDP ratio also falls below the 60 per cent threshold at 57.9 while Finland exceeds it at 73.2. This said, neither fits the stereotype of an unresponsive, lethargic welfare state.)

What ultimately distinguishes Denmark and the other Scandinavian countries is their commitment to best practices that deliver better services at lower costs, regardless of political concerns and institutions that increase transparency and decrease corruption.

Wolfgang Depner has a PhD from the University of British Columbia. He teaches philosophy and Canadian history at Royal Roads University.