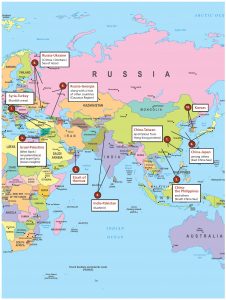

Wolfgang Depner surveyed the planet’s Top-10 most dangerous dispute zones and came up with this list.

Problems of territoriality lie at the heart of global politics, especially among those who subscribe to realist theories of international relations.

If we accept their argument that the international community consists of independent states that exist in an environment of anarchy thanks to the absence of a global authority, then any study of their relations inevitably focuses on their boundaries. As philosopher Max Weber said, a state is a “human community that claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.”

Or as Jeremy Larkin, lecturer in international relations at Goldsmiths, a college of the University of London, puts it: “All states, regardless of historical and geographical variables, are assumed to have some physical extension in space, to occupy an identifiable place on the surface of the Earth, to have borders that clearly distinguish inside from outside and self from others.”

But if ability to “distinguish inside from outside and self from others” appears as an element of statehood, it is a necessary but insufficient condition for it.

Equally necessary is Weber’s point about the exercise of exclusive authority — the concept of sovereignty — within that territory. It is one thing to claim a set of boundaries, it is another to control the space within them, as the Communist government of mainland China has discovered in Hong Kong, where protesters have challenged its authority. (Whether this authority is legitimate is another question.)

But if these points have “assumed the status of a common-sensical, self-evident truth,” as Larkin writes, it has not always been this way.

As he writes, the concept of territoriality in modern international relations is a social construct that only fully emerged in the period after the end of the 30 Years’ War (1618-1648). When married with the ideas of national self-determination (late 18th and early 19th Centuries) and social Darwinism (late 19th, early 20th Century), it subsequently contributed to the catastrophes that defined the first half of the 20th Century.

They, in turn, have inspired international institutions and instruments that attempt to ameliorate territorial conflicts, in line with the liberal school of international theory.

This said, powerful actors with nationalistic agendas in North America, Asia, Europe and the Middle East have since regained the upper hand in this conflict between realism and liberalism by either emphasizing their own territorial integrity, or worse, revising the borders of others.

This list of the 10 most important unresolved territorial disputes draws attention to this dynamic.

To be clear: Territorial disputes have always been, and will be, features of international systems, and every dispute described in this list has had a long history dating back decades, if not centuries, as in the case of the ethnic-religious conflicts that continue to rile the ”near abroad“ of Russia.

But their saliency has risen in what Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group, and Nouriel Roubini, professor at New York University, have described as a G-Zero World, in which no nation is either willing or capable of guiding the international system, be it through the punishment of pariahs or the provision of public goods. In this world, deprived of global leadership and defined by increasingly dysfunctional global institutions and instruments, states will increasingly find themselves on their own, a condition some actors actually encourage.

As cacophony replaces co-operation, conflict will become more likely, and many observers have already argued that we currently find ourselves in the middle of a new Cold War between the declining United States and emerging China, with neither side concerned about any collateral damage that they might be causing to the larger international system.

So what stands out about the list? As already mentioned, many of these conflicts have had a long history, often involving key historical events themselves. Second, they unfold within larger conflicts. For example, the conflict between China and Taiwan is not just about the status of Taiwan. It is also about the conflict between China and the United States. Third, these territorial conflicts serve domestic purposes. For example, when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu promised to annex the West Bank — the very core of a future Palestinian state — earlier this year, he did so for electoral purposes and greater security. He tried the same gambit when Israelis went to the polls again in September.

Domestic politics also explain the recent move by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to strip the Indian part of Kashmir of its previously enjoyed autonomy rights in playing to his nationalistic base. Another example concerns Russia. It finds itself in the middle of multiple territorial disputes with its neighbours, but has shown little interest in solving them, partly because Russian President Vladimir Putin uses them to stoke nationalist sentiments against the West, thereby distracting the Russian public from domestic problems. This is partly because Putin continues to see Russia as a genuine global power. This said, it is also important to acknowledge that these territorial claims reflect — at least in the minds of those who pursue them — attempts to resolve genuine security problems. Finally, none of these conflicts is “local.” Any prolonged tensions in the South China Sea would not just reverberate through the immediate region, but also impact other parts of the world, be it through global stock markets, or, less abstractly, by disrupting global supply lines.

1. China-Taiwan (and fallout from Hong Kong protests)

It’s a global drama by any measure: the fate of the sometimes violent anti-mainland China protests in Hong Kong that have sometimes sent more than a million defiant citizens into the streets. And it resonates with special significance among the 24 million or so residents of Taiwan.

It’s a global drama by any measure: the fate of the sometimes violent anti-mainland China protests in Hong Kong that have sometimes sent more than a million defiant citizens into the streets. And it resonates with special significance among the 24 million or so residents of Taiwan.

When the former British Crown colony returned to mainland China in 1997 under the formula of “one country, two systems,” Hong Kong also became a possible model for the future of Taiwan, which Beijing considers a breakaway province. Chinese President Xi Jinping himself raised it in January 2019, when he called on Taipei to start unification talks on that basis. Taiwanese leaders, starting with President Tsai Ing-wen, rejected his demand and questioned Beijing’s commitment to the “one country, two systems” approach. Months later, events in Hong Kong have confirmed these fears, and Chinese actions in Hong Kong have confirmed the worst suspicions of those who also read Xi’s speech as a veiled threat of invasion should Taiwan ever declare independence.

First, the good news. According to a report to the U.S. Congress — the latest China Military Power Report — China currently lacks the means to invade Taiwan. While mainland China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) continues to “improve training and acquire new capabilities for a Taiwan contingency,” the report finds “no indication that China is significantly expanding its landing ship force necessary for an amphibious assault on Taiwan.”

Now, the bad news. Cross-strait relations between China and Taiwan have become increasingly prickly because of recent developments, starting in January 2019, when Ing-wen challenged the 1992 Consensus, an agreement that acknowledges the existence of one China. But it also allows for their varying interpretation on China’s legitimate government. This ongoing historical conflict followed the Chinese civil war from 1945 to 1949 in which the Communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the Nationalists’ Kuomintang Party under Chiang Kai-shek, whose government, assets, partial military and followers moved to Taiwan (then called Formosa). According to the interpretation by the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations, the core of the 1992 Consensus consists of the “tacit agreement” that Taiwan will not seek independence.

By questioning the 1992 Consensus, Ing-wen leaves open the possibility that Taiwan could declare independence, one of the scenarios that the PLA had previously identified as a reason for the use of force. While presidential elections in 2020 will test the popularity of Ing-wen and her diplomatic ideas, China has already signalled its displeasure by accusing Taiwan of “pursuing a path of separatism” while refusing to rule out China’s use of force.

All of this has happened after Taiwan purchased military equipment worth more than $2.2 billion from the United States, and began a diplomatic charm offensive during which Ing-wen met with the United Nations ambassadors of the countries that recognize Taiwan, despite pressure from China.

While not a member of the United Nations, Taiwan maintains an unofficial consular office not far from the UN and formal diplomatic ties with 16 UN members, mainly from Latin America, the Caribbean and the Holy See. Taiwan also maintains unofficial ties with 50-plus other UN members. This said, the number of countries that recognize Taiwan as the sole representative of China has been dropping. (Taiwan, for its part, recognizes every UN member except for China and North Korea.)

Taiwan can continue to count on U.S. support, which intensified when then-U.S.-president-elect Donald Trump accepted a congratulatory call from Ing-wen in December 2016. The 10-minute phone call upended almost four decades of American policy, because no American president had spoken with a Taiwanese leader since 1979, when the United States withdrew diplomatic recognition of Taiwan under the “One China” policy that accepts mainland China (the People’s Republic of China) as the sole government of China. Trump, being Trump, then bragged about the phone call on Twitter and further raised doubts when he said that the United States did not have to follow the policy.

Interpretations of this move varied, from deliberate provocation of Beijing to rookie mistake to clever negotiating ploy. Beijing downplayed the incident, arguing that Trump had fallen for a “little trick” played by Taiwan, but it now appears it was part of a larger strategy aimed against China that has relied, for the most part, on economic tools.

But Taiwan remains the one place where U.S. and Chinese military forces are the most likely to clash. U.S. Navy ships routinely transit the Strait of Taiwan on the premise that they are international waters, but they’re also signalling to China that the United States won’t accept efforts to push it out of the region. China routinely conducts live-fire exercises in the area, and while China has committed itself to peaceful unification, it has never ruled out the use of force.

2. Strait of Hormuz Region

As the only route to the open ocean for one-sixth of global oil production and one-third of the world’s liquefied natural gas (LNG), the 39-kilometre-long Strait of Hormuz, lying between Iran and Oman, is the world’s single most important oil passageway.

As events during the summer of 2019 have shown, conflicts along this global chokepoint can rattle markets and raise the spectre of war throughout the Middle East.

Perhaps lost in this tableau of tension is the disputed status of three local islands near the Strait. While Abu Musa, Greater Tunbs and Lesser Tunbs add up to fewer than 26 square kilometres of sand and scrub, they screen the entrance into the strait.

Iran has, on several occasions, threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz if the United States or Israel launch a military attack against its nuclear installations, and the islands would likely play a significant role in any Iranian counterstrike against shipping.

The origin of this dispute dates to the late 19th Century, and for decades, Iran and United Arab Emirates claimed sovereignty over the islands, with Iran seizing them in 1971, just before the UAE formally declared itself an independent state.

Since then, Iran has militarized them with small boat harbours, airstrips and, as reported by Forbes, “presumably, a full suite of missiles, radars and other surveillance gear.”

These islands, themselves part of a broader network of forward maritime outposts, have allowed Iran to “advance a strategy of bravura and bluster” that extends its influence.

“Ultimately, Iran has been too successful in demonstrating that small maritime holdings,” Forbes notes, “when combined with continuous bellicose provocation, are force multipliers.”

Regional and international efforts to resolve this territorial conflict have been ongoing and actually resumed in late July 2019, when a UAE delegation travelled to Iran. The development marked an easing of tensions between the countries, which have also found themselves on opposite sides of the civil war in Yemen, with Iran backing Houthi rebels in Yemen, while the UAE has joined Saudi Arabia in sending money and men in support of Yemen’s official government. These talks have coincided with a scale-back of UAE’s involvement in Yemen, suggesting that the recent run of tensions in the region marked a peak, if only for the present.

3. Israel-Palestine territories (West Bank/Jerusalem/Gaza) and Israel-Syria (Golan Heights)

To sample the current opinions of some Israeli historians about the future of their country is to drink deeply from a well of despair.

In commemorating the late liberal Israeli author Amos Oz, Israeli author-historian Tom Segev argues in The New Yorker that the prospects for a viable peace between Israelis and Palestinians have been fading since 1993, when the Oslo Accords inspired Arab terrorism and the assassination of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995 by an ultranationalist opposed to a Palestinian state existing next to Israel. Within months of “one of history’s most effective political murders,” Benjamin Netanyahu started to steer Israel towards its current settlement policies in the West Bank. Almost 25 years later, Israeli settlers in the Occupied Territories now number nearly half a million, “in effect foreclosing on the idea of a two-state solution,” Segev writes.

Israeli historian Ilan Pappé agrees with the futility of pursuing a two-state solution in arguing for a pacifistic and humanistic alternative to Israel in the form of a binational state with a socialist economic system and equal rights for all its citizens, contrary to the current apartheid-like state, as he describes Israel.

If Pappé is pro-Palestinian, fellow historian Benny Morris predicts a future in which demographic developments will render Jews a persecuted minority in their own state, with the lucky ones able to escape to the United States.

For all their differences, these perspectives are pessimistic about the current viability of the land-for-peace formula behind the Oslo Accords, the idea that Israel would eventually withdraw to the borders of 1967 in exchange for formal recognition by a future Palestinian state.

While the two-state solution enjoys broad formal support in the United Nations General Assembly and among key powers in Asia and Europe, developments, namely the expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, the very location of a future Palestinian state, and divisions among Palestinians themselves, have steadily worked against it.

As Canadian Michael Lynk, the special rapporteur appointed by the UN Human Rights Council recently said, the UN considers Israeli settlements illegal. But factionalism between Fatah — the more moderate Palestinian authority in the West Bank — and Hamas — the radical Palestinian authority in the Gaza Strip with a long history of deadly attacks against Israelis — has played into the hands of those who see the Palestinians as obstacles to peace and progress.

So what is to be done? The latest efforts, as proposed by Jared Kushner, the son-in-law and senior adviser of Donald Trump, focus on peace through prosperity as part of a larger, yet-to-be-released Middle East peace plan described as the ”deal of the century.”

Critics, including The Wall Street Journal, hardly a liberal outlet, argue that this idea ignores the facts on the ground. They question the impartiality of the United States after its 2017 decision to formally recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, a major diplomatic affront to the Palestinians who also claim it.

Ordinary Palestinians in the West Bank, for their part, face difficult choices. Violent resistance appears ineffective in the face of superior Israeli forces, yet few see other alternatives. The prospect of peace through prosperity as promised by current negotiations might be appealing, but many are not buying the hype for any number of reasons. They include infrastructure deficiencies, barriers to the movement of goods and people and the absence of predictable rules. Ultimately, many Palestinians see current efforts as a cynical bribe to buy off a long-cherished dream.

As for the Golan Heights, Israel continues to occupy it for security reasons, and like the West Bank and Gaza, it remains a flashpoint of tensions, as Syria recently reiterated its right to recover the Heights.

4. India-Pakistan (Kashmir)

“We want revenge, not condemnation. It is time for blood, the enemy’s blood.” So spoke Arnab Goswami, one of India’s most prominent television journalists after a male suicide bomber had killed more than 40 Indian paramilitary soldiers on Feb. 14, 2019 in Pulwama, a city in the Kashmir region.

The suicide bomber was a member of Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), a Pakistan-based group that aims to unite the Indian portion of Kashmir with Pakistan through attacks on symbols of the Indian state.

Goswami and other bellicose moderators baying for blood received their wish days later when India, having accused Pakistan of harbouring the group, launched airstrikes on Feb. 26 against what it says was a JeM training facility beyond the de-facto border that divides India-administered Kashmir from Pakistan-administered Kashmir following a war between the two countries in 1971.

Developments escalated quickly from there. A Pakistani counterstrike on Feb. 27 sparked an aerial battle that led to the downing of two Indian jets and the capture of an Indian pilot by Pakistani forces. Video footage showing the pilot bloodied and bruised only heightened tensions and fear of a full-out war between two nuclear powers prompted calls for restraint from leaders around the world.

Both sides eventually de-escalated their rhetoric by sending signals of restraint. Pakistan, for example, quickly released a new video of the captured pilot showing him cleaned and sipping tea before eventually releasing him. But the episode was nonetheless a terrifying reminder of the incendiary potential that the Kashmir conflict bears.

The split itself dates back to the hasty and poorly planned partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Once a princely state, Kashmir found itself free to choose between India and Pakistan following partition. Both governments soon pressured Kashmir, which eventually sought military help from India, after rebels sponsored by Pakistan seized control of western Kashmir. India agreed to the aid, but only after Kashmir had formally become India’s.

Two years of war followed, ending with a ceasefire sponsored by the United Nations.

Kashmir was also the primary cause of conflict between the two countries in 1965 and 1999. The 1971 war that led to the independence of Bangladesh also flared up in Kashmir.

So Kashmir has been a fault-line, if not the fault-line, of Indo-Pakistani rivalries since 1947, with both claiming full control of the region for apparent reasons.

For India, Kashmir is the place to showcase the rights of Muslims within Indian society, as its 45-per-cent share of Kashmir is the only Indian region where Muslims constitute a majority, at 60 per cent of the local population. This is also the reason Kashmir is so important to Pakistan and its self-image as the Muslim homeland on the subcontinent.

The respective regions of Kashmir under Indian and Pakistani control are also far from homogeneous, with groups on either side of the border chafing under their respective governments. Finally, China also plays a small but important part through its own claims to the region.

While these political complications are familiar, the complexity of their interactions has changed. Modern information technologies can quickly condense and convert news of local tensions in the region into national grievances with global consequences. Fed by nationalistic furor, decision-makers on both sides might soon find themselves prisoners of cascading events that they might have started, but can no longer stop.

5. China, the Philippines and others (South China Sea)

Thucydides’ Trap refers to the theory that war is the likely outcome whenever a rising power rivals a ruling power, and the South China Sea, along with the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea, are the most likely places where it could snap into place.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the South China Sea to global commerce. In 2016, goods worth US$3.37 trillion passed through the area, including large amounts of oil and liquefied natural gas. More than 80 per cent of Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese oil imports travel through the South China Sea. Overall, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimates that one-third of all global shipping passes through the area, with China holding the lion’s share. (By way of background, China exported goods worth $874 billion through the area in 2016, while importing goods worth $598 billion).

In short, the South China Sea is an essential maritime crossroads for trade for many of the world’s largest economies, starting with China, but also the already-mentioned Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, as well as Vietnam, among others.

But the region is not just a “vital artery” of global trade, as the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies writes. It is also an untapped depository of strategic resources, with an estimated 11 billion barrels of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Disputes over who owns which share of this would-be bounty date back to the 1970s, but have significantly intensifiedd in recent years, during China’s economic and — therefore — political rise.

China, for example, claims sovereignty over the Spratly and Paracel island groups and other land features within its self-proclaimed “nine-dash line,” which runs as far as 2,000 kilometres from the Chinese mainland, claiming 90 per cent of the contested waters. Citing unclear “historical maritime rights,” China claims that it owns any land or features contained within the line, which comes within a few hundred kilometres of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. China has also claimed sovereignty over the waters in the area, as well as its “seabed and subsoil thereof.”

The Economist reports that these “absurdly aggrandizing territorial claims” have sparked tensions with neighbours both near and far, including the Philippines, which found itself on the winning side of a 2016 tribunal ruling that found that Chinese claims justified by the “nine-dash line” could not exceed its maritime rights under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention, which states that nations have sovereignty over waters extending 12 nautical miles from their land and exclusive control over economic activities 200 nautical miles out. Yet China has shown little interest in fulfilling the binding ruling. It has actually gone out of its way to create facts on the ground by transforming reefs in the Spratly Islands group, claimed by the Philippines, into island fortresses.

Chinese strategic bombers have conducted takeoff and landing drills on Woody Island in the Paracel Islands, where Chinese interests clash with those of Vietnam and Taiwan.

The United States, meanwhile, has challenged Chinese claims through Freedom of Navigation Operations, sending ships and airplanes through the area in defiance of the Chinese argument that foreign militaries cannot conduct intelligence-gathering activities, such as reconnaissance flights, in its exclusive economic zone. According to the United States, they can under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

This is where Thucydides’ Trap comes into play. While China may feel it acts in self-defence by expanding its military capabilities in the region — an area of genuine strategic importance for economic reasons — others interpret China’s actions as aggressive, if not hostile. Escalation begets escalation and eventually the trap springs.

6. China and Japan, among others (East China Sea)

Nearly 75 years after its conclusion, the Second World War continues to cast a shadow around the world, and many will inevitably interpret contemporary developments through its lens. The Second World War remains an especially divisive subject in the relations between Japan and China. China’s suffering at the hands of Imperial Japan can be compared to that of the Soviet Union at the hands of Nazi Germany, with one of the differences being that Japanese aggressions and atrocities against China — known as the Rape of Nanking (1937) — predate the agreed-upon starting point of the Second World War (1939) and the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. (1941) by years. Modern-day Japan, like modern-day Germany, bears no resemblance to the country that waged war on its neighbours.

Yet controversies continue to simmer just below the surface, despite the existence of a friendship treaty signed 40 years ago. Whitewashing descriptions of the war found in Japanese textbooks and visits by Japanese politicians to religious shrines honouring war criminals have caused tensions in the past. Japan’s neighbours also continue to monitor efforts aimed at changing Japan’s post-war pacifistic constitution. Though those attempts have so far proven unsuccessful, any successful changes in the future could thicken this tableau of grievances by stoking anti-Japanese sentiments in the region.

As for Japan, it sees China as an economic rival whose economy has surpassed its own, and a country eager to match its global economic clout with commensurate military might. China also impacts Japanese security through its regional ally, North Korea, whose nuclear and ballistic capabilities remain the source of grave, if not existentialist, concern. Yet Japan finds itself increasingly marginalized from diplomatic discussions, a situation made worse by fraying ties with what should be a natural ally, South Korea.

As if all these circumstances are not complicated enough, Japan and China have also made overlapping claims to five uninhabited islands and three rocks in the East China Sea — the Senkaku Islands as the Japanese call them, or the Diaoyu Islands, as the Chinese call them.

Japan currently administers the islands, but China and Taiwan have made claims to them.

The land itself is not valuable, but the sea around it — or better, what lies underneath the seabed — could be, as the East China Sea contains oil and natural gas, with the actual amount subject to speculation.

The islands themselves also lie within the Acheson Line, a U.S. defensive perimeter running from the Aleutian Islands of Alaska through Japan’s Ryukyu Islands to the Philippines, bearing the name of Dean Acheson, secretary of state under Harry S. Truman. As such, they are part of a larger security infrastructure, a sort of maritime trip wire.

To ease tensions along it, China and Japan have recently agreed to a series of measures, including a hotline, for the purpose of defusing the type of maritime confrontations that have roiled relations in the past.

7. Syria-Turkey (Kurdish areas)

When Russian President Vladimir Putin hosted Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at the Russian resort of Sochi in February 2019 to discuss the future of Syria, it was not hard to draw comparisons with the Yalta Conference of 1945, when the then-allied United States, Britain and former Soviet Union discussed the post-war future of soon-to-be defeated Nazi Germany and the rest of Europe.

While the analogy only goes so far, Putin, Erdoğan and Rouhani can be confident in the knowledge that they can count themselves among the winners of the Syrian civil war — at least for now. Their respective contributions to the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad have earned them a compliant client of diminished status.

It is telling that al-Assad has been conspicuous by his near-absence from diplomatic gatherings, which his patrons have organized, ostensibly for his benefit. This was the case in February 2019, when the three self-appointed “guarantor countries” pledged to preserve the territorial integrity of Syria.

This promise, however, is not just a warning to other foreign actors (the United States and Israel), and internal opponents of the al-Assad regime, including the Kurds and remaining rebels, but also an implicit acknowledgement that Turkey and Syria have their own mutual history of territorial disputes that could easily flare up again.

An historical source of conflict between both countries has been the status of Hatay province. France — Syria’s former colonial master — transferred the region to Turkey in the late 1930s as part of deepening diplomatic ties, much to the chagrin of Syria, which officially considers this “lost province” still part of its own sovereign territory following Turkey’s official annexation in 1939.

A more immediate concern for both sides is the continued existence of Rojava, the name of the Kurdish-controlled area that juts out like a triangle into the northeastern corner of Syria with the Euphrates River as its base. Syria, which stands to lose one-third of its territory, and Turkey are among the enemies of this embryonic Kurdish state, yet they appear at odds over their next steps.

While al-Assad’s regime has focused its attention on the last rebel stronghold of Idlib in the northwestern corner of Syria, Turkey has been toying with the idea of a more forceful intervention into Syria that would go beyond efforts in early 2018 when it sponsored and supported an invasion and occupation of the Kurdish enclave of Afrin.

Such a move would not only further sour relations between Turkey and the United States, which broadly backs the Kurds, but also unleash an unpredictable dynamic in the region.

This fear of an unco-ordinated Turkish intervention rings loud and clear through the final declaration of the Erdoğan-Rouhani-Putin summit, which commits its signatories to “co-ordinate their activities” in northeastern Syria to “ensure security, safety and stability in this area, including through existing agreements, while respecting sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the country.”

While internal strife defines the Kurdish area of northwestern Syria, the continued and growing presence of something resembling a Kurdish state might well convince Erdoğan to break that deal.

8. Russia-Ukraine (Crimea/Donbass/Sea of Azov)

The election of former comedian Volodymyr Zelensky as the new president of Ukraine in April 2019 could have marked a turning point in its relations with Russia.

Zelensky — unlike his predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, whom he defeated by a wide margin — had campaigned on a conciliatory approach towards Russia following its illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and its continuous support for pro-Russian separatists in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine.

Several factors accounted for this shift. They include public opinion (75 per cent of Ukrainians said in a survey that they would support direct talks with Moscow to restore peace to the Donbass) and the realization that Russia holds — at least for now — the better cards in this conflict, which has so far killed 13,000, driven at least 1.6 million from their homes, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and transformed one of the most productive regions in Europe into a muddle of physical devastation and death.

Yet Russian President Vladimir Putin has chosen to respond with confrontation. Hours after Zelensky’s election, Moscow sped up the issuance of Russian passports to residents living in the disputed regions.

While Putin defended the move on humanitarian grounds, it sparked sharp protest from Western voices, who denounced it as a provocation straight out of the Russian playbook for so-called frozen conflicts, “nasty small wars,” according to The Economist, that deliberately remain unresolved with the larger purpose of undermining the development of neighbouring countries by way of challenging their territorial integrity. As The New York Times wrote, by populating the disputed area with Russian citizens, Moscow creates the very excuse to intervene on their behalf in the future, should the need ever be invented or emerge.

The Donbass is, of course, not the only region where Russia can and has tested the mettle of Ukraine. By building a bridge over the Strait of Kerch, Russia has not only physically connected Crimea to the rest of its realm; it is also slowly choking parts of the Ukrainian economy. The bridge has limited the size of ships that can now enter the Sea of Azov from ports outside of it, and worse, works like a maritime rampart from which Russia can control shipping traffic.

This new reality has hurt business in the Ukrainian port cities of Berdyansk and Mariupol, with the latter being a key industrial and logistical centre in the Donbass region, not far from areas that Russian separatists control.

It is against this background that Ukrainian and Russian naval forces clashed in November 2018, with Russia capturing 24 Ukrainian sailors when their ships tried to pass through the Strait of Kerch to reach Mariupol. Their return in September as part of a larger exchange between Russia and Ukraine has eased current tensions, but hardly changed the larger dynamic.

9. Russia, Georgia, along with a host of other countries (Caucasus Region)

Poorly chosen words can easily cause an eruption in the Caucasus, a simmering cauldron of ethnic, religious and political conflicts created over centuries, if not millenniums.

Consider what happened in July 2019 when a Georgian television journalist called Putin a “filthy invader” live on air. The Russian response to this insult was almost immediate, in the form of a flight ban that hit Georgia’s tourism industry, a major source of foreign revenue. (Georgian officials estimated the absence of about one million Russian tourists — about 70 per cent of the annual total — will cost their economy $710 million in lost revenue).

The insult-riddled rant triggering the Russian response came after a visiting Russian legislator had spoken Russian from the speaker’s chair of the Georgian parliament in Tbilisi days earlier. The short speech sparked protests inside and outside of the building, with many protesters accusing the government of collaborating with Russia over the status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two regions officially part of Georgia, but effectively under Russian control, after they had refused to recognize Georgian rule following the break-up of the Soviet Union.

Russia (along with, by latest tally, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru and Syria) recognizes the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia following a short war between Georgia and Russia in 2008.

With a combined population of 290,000 people and an area of 12,560 square-kilometres, both regions account for 6 per cent of Georgia’s population and 20 per cent of its territory.

For Russia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia represent the means to a larger end, namely denying Georgia deeper relations with the West, including membership in NATO.

Another hot spot in the Caucasus is the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, two former Soviet republics locked in a decades-long dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh, a majoritarian ethnic Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan’s international borders.

Armenians and Azerbaijanis have contested the area before, during and after the Soviet period, with ethnic violence during the final days of the Soviet Union escalating into a war that lasted six years (1988-1994), claimed a combined 20,000 lives and displaced hundreds of thousands. The area itself remains under the control of ethnic Armenians, who have declared its independence, though that move was recognized by none.

While the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has been trying to convert the 1994 ceasefire into a permanent resolution, armed flare-ups continue to threaten the fragile truce in the area.

Russia’s role in this conflict is more complex. It has counselled restraint whenever full-blown war between Armenia and Azerbaijan looms on the horizon and has hosted negotiations, as recently as April 2019, following another flareup, as co-chair of the OSCE’s Minsk Group, along with France and the United States.

But Armenia and Azerbaijan are suspicious of Russia’s motives. Armenia’s status as Russia’s lone remaining ally in the region has raised questions about Russia’s impartiality. Armenians, meanwhile, might ask themselves how much actual influence they enjoy in Moscow, since Russia also sells weapons to Azerbaijan. In fact, it has been the main supplier of arms to both sides. Russia, in other words, profits from instability.

10. Koreas

The list of issues dividing the Koreas — which technically remain at war — is a long one, starting with North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic capabilities, the existence of which pose a global security threat. It also includes a dispute about maritime borders, specifically the status of what the literature describes as the The Northern Limit Line, the inter-Korean maritime border claimed by South Korea, but challenged by North Korea. Both sides have exchanged fire at that location in the past and it looms large in the public consciousness of both Koreas. A brief 2002 naval battle inspired one of South Korea’s highest grossing films and security lapses along the line have recently led to the sacking of a South Korean general after a wooden fishing boat carrying four North Korean defectors managed to cross the intensely monitored sea between the two countries and dock undetected. Notably, two returned.

10 long-simmering and newer conflict zones

1. Kosovo-Serbia (northern Kosovo)

A century ago, following the First World War, diplomats stitched strands of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire into the state that was Yugoslavia during the Paris Peace Conference.

Multiple wars with some of the worst human rights abuses in recent memory have since shredded their work into a pastiche of states whose mutual bonds consist of shared suspicions that border on open hostility. Relations between Kosovo and Serbia offer the best view of this topography of tension.

More than one decade after Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008, the boundaries of both remain in doubt, with consequences for regional, even global, stability.

Neither recognizes the other, and each can count on a powerful cast of supporters on the international stage. Exactly 100 members of the United Nations, including the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany, recognize the independence of Kosovo. Meanwhile, Russia, India, China and a handful of European Union members (including Spain) support Serbian claims to Kosovo.

These opposing international coalitions have accorded this regional conflict on the southeastern fringes of Europe global salience that far exceeds the respective significance of the principal actors. Home to fewer than two million people, Kosovo is barely larger than Cape Breton Island, while Serbia, with its seven million, is hardly larger than New Brunswick.

Yet the obstacles between them remain immense and inspired a simple remedy: a swap of contested territories with an accompanying exchange of populations.

Under the proposal, Kosovo would receive the Presevo Valley with its mostly ethnic Albanian population in southern Serbia, while Serbia would regain full control of a region in northern Kosovo mainly populated by Serbs.

The appeal of this idea is apparent: Muslim Kosovars would live in Kosovo, while Orthodox Christian Serbs would live in Serbia. In exchange for this territorial trade, both countries would recognize each other, thereby paving the path for Kosovo to become a member of the UN and for both to join the European Union.

Yet this tempting idea bears many dangers, key among them the precedent it would set: If both parties agreed to change now, what would stop competing ethnic groups elsewhere in the region from making comparable demands?

The whole idea also echoes a past period of international relations, when the drawing of political borders was the domain of large powers, done above the heads of smaller parties.

2. Arctic

If the Antarctica treaty aims to avoid “international discord” (see entry below) in the South Pole region, the North Pole is becoming increasingly rife with rivalries. While territorial disputes in the region predate the Second World War and the Cold War, changes in the global climate continue to whet the commercial ambitions of Arctic countries. This dynamic accounts for Donald Trump’s offer on behalf of the United States to purchase Greenland.

In June, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo identified the Arctic’s rapidly shrinking ice levels as a business opportunity in downplaying the existentialist threat that climate change poses. “The Arctic is at the forefront of opportunity and abundance,” Pompeo said during a recent meeting of the Arctic Council in Finland. “It houses 13 per cent of the world’s undiscovered oil, 30 per cent of its undiscovered gas, an abundance of uranium, rare earth minerals, gold, diamonds and millions of square miles of untapped resources, fisheries galore.” During that same occasion though, Pompeo’s rhetoric also previewed the tensions that lie ahead when he rattled off a series of warnings aimed at Russia, China and Canada over “illegitimate” claims in the region concerning issues such as the Northwest Passage and the Beaufort Sea.

3. Antarctica

In 1960, The New York Times called The Antarctica Treaty “a bright spot in an otherwise gloomy landscape of international relations.” Sixty years after its signing in 1959, the sentiment remains true. Developed after clashes between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1948 and during the early days of the Cold War, the treaty reserves the continent exclusively for “peaceful purposes” in elevating collective goals such as scientific inquiry and environmental protection above resource exploitation and territorial ambitions. Specifically, Article IV states that no “acts or activities taking place while the present treaty is in force shall constitute a basis for asserting, supporting or denying a claim to territorial sovereignty in Antarctica or create any rights of sovereignty in Antarctica. No new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim, to territorial sovereignty in Antarctica shall be asserted while the present [treaty] is in force.” This said, the treaty’s language also recognizes sometimes overlapping territorial claims by Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom, as well as the rejection of those claims by others. The United States and Russia also maintain a “basis to claim” territory without having made a claim themselves. In short, the treaty tries to preserve the status quo, perhaps a futile effort in light of technological and climatic developments that would improve access to Antarctica’s long-term prize — oil, natural gas and ores. The current ban on mining could come up for review in 2048 and by that time, the region and the world could look very different.

4. Cyprus (Turkish Republic of North Cyprus Turkey / Cyprus)

Niayazi Kizilyurek became an historic figure in May 2019 when he joined the European Parliament as the first Turkish Cypriot, while running for a Greek Cypriot party. Kizilyurek, in other words, personifies what many on and off the Mediterranean island envision: a future beyond the divisions that have separated the island into a Greek-speaking south and Turkish-speaking north since July and August of 1974, when the Turkish army invaded northern Cyprus to first forestall Greek annexation of the entire island, then expanded its initial gains following failed peace talks. These events led to the current split of the island into the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which only Turkey recognizes.

While the list of failed proposals to unite the island appears long, many considered Kizilyurek’s election a catalyst that could reignite reunification efforts. Months later, this optimism has been lost as territorial tensions flare up again.

The irritant has been Turkey’s decision to drill for gas off Cyprus’s coast following its discovery this year. Cyprus considers the Turkish drilling sites part of its own exclusive economic zone. Ankara argues that Cyprus cannot unilaterally make agreements about exclusive economic zones and energy explorations with surrounding countries. Turkey also claims the area as part of its continental shelf.

Turkey’s decision to drill appears to pursue a larger goal: to force deeper economic ties between the northern and southern parts of the island, and thereby expand Turkey’s influence on the island beyond its existing domain.

The European Union, which has not taken kindly to these moves, imposed sanctions on Turkey for what it calls “illegal drilling” in the territorial waters of a member state. Yet Turkish officials appear unimpressed for reasons that speak to the tense and ultimately unbalanced relations between the European Union and Turkey. Thanks to the cash-for-refugee program signed in 2016, Turkey has practically served as Europe’s bouncer in stopping migratory streams from the Middle East and elsewhere, with millions of refugees already in the country remaining in limbo.

Their presence has become increasingly unpopular for multiple, but mainly economic, reasons and Turkey has already shown its willingness to use them as leverage by threatening to “open the gates,” as it did in 2016.

A comparable move could force the EU to choose between two unappetizing options: tolerate Turkish incursions into Cyprus’s territory, with the accompanying loss of credibility, or respond with tougher measures that would only worsen relations with Turkey, an important regional actor in an already volatile region.

5. Southern Kuril Islands

Following the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union occupied all of the Kuril Islands, with Japan challenging Russian control of the four most southern ones. Their disputed status has delayed a formal peace treaty between the two sides, and remains an ongoing irritant in Russo-Japanese relations. When Tokyo circulated a map during the recent G20 meeting in Osaka that showed them as part of Japan, Russia filed an official diplomatic protest. Japan then did the same after Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev visited one of the islands, dashing hopes of a resolution — at least for now.

6. Abyei, Sudan/South Sudan

Decades of civil war have led to the split of Sudan into a scaled-down version of Sudan and South Sudan. Yet nearly a decade after this division, the demarcation line remains an area of deadly violence. Consider the region of Abyei, an oil-rich area claimed by both Sudans, where the presence of a United Nations peacekeeping mission has failed to curb the violence. In fact, the mission has come under fire itself. (While the region voted to join South Sudan, the legitimacy of this outcome is questionable, after members of the Misseriya tribe refused to participate in the referendum, thereby leaving the local Dinka to determine the eventual outcome). This said, tensions along the Sudan-South Sudan border merely appear representative of the internal strife that has gripped both Sudans.

7. Tibet

The preservation of Tibet’s cultural, religious and linguistic identity — not the restoration of its independence — now drives the Dalai Lama. “It’s no longer a struggle for political independence,” he said in a recent interview. China, however, continues to speak of “external separatist forces” in relation to Tibet as per China’s white paper titled, China’s National Defense in the New Era, released in July. It accuses the Tibet leadership of posing “threats to China’s national security and social stability.”

While such claims stretch credulity, China remains extremely sensitive to any pro-Tibetan sentiments 60 years after Chinese forces throttled an uprising.

8. Transnistria

The self-proclaimed Pridnestrovian Moldovian Republic officially belongs to the Republic of Moldova, but has nonetheless managed to survive as a de-facto relic of the Cold War by the graces of Moscow. Snaking along the Dniester River for the most part, it exists in the same category as South Ossetia and Abkhazia: small embers of land with which Russia can easily stoke broader conflicts.

9. Beaufort Sea

Environmentalists have denounced the immediate exploration of portions of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska as an unnecessary destruction of one of the most pristine and precious pieces of nature, with one New York Times columnist comparing this decision to junkies who “stoop low enough to steal their mothers’ jewels” to satisfy their habits. “Part of the tragedy of the Arctic Refuge is that its integrity is to be sacrificed, not to meet a national emergency or vital economic needs, but out of spite,” writes William deBuys, a conservationist. American ambitions in the refuge, believed to sit atop one of the last great onshore oil reserves in North America, also concerns Canada. Detrimental environmental effects will inevitably impact Canada, and the current run-up to drilling on the American side draws attention to the U.S.-Canada dispute over the exact location of the maritime border in the Beaufort Sea. Both claim a pie-slice-shaped piece of the Beaufort Sea, whose icy waters also cover large oil and gas reserves.

10. The moon

As various state and non-state actors rush to return to the moon with their eyes towards a permanent presence, it is worth remembering that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty governing the activities of states on celestial bodies prohibits any national government from claiming any territory in space as their own. Follow-up agreements have since confirmed this approach. But critics wonder whether it will stand up to challenges by pointing to the absence of international institutions capable of enforcing it. The world’s three leading space powers — the United States, Russia, and China — along with some member states of the European Space Agency and Japan have also refused to sign the 1979 Moon Treaty, a follow-up to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

As various state and non-state actors rush to return to the moon with their eyes towards a permanent presence, it is worth remembering that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty governing the activities of states on celestial bodies prohibits any national government from claiming any territory in space as their own. Follow-up agreements have since confirmed this approach. But critics wonder whether it will stand up to challenges by pointing to the absence of international institutions capable of enforcing it. The world’s three leading space powers — the United States, Russia, and China — along with some member states of the European Space Agency and Japan have also refused to sign the 1979 Moon Treaty, a follow-up to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

The most recent successful moon venture was China’s January 2019 landing on the ‘dark side of the moon’ — the side not visible from Earth. The Chang’e 4 – a combined space lander and rover will probe soil composition and carry on astronomical studies. It is partial fulfilment of President Xi Jinping’s 2013 promise upon becoming president: “The space dream is part of the dream to make China stronger.”

Unless agreed upon by an international regulatory body, the Moon Treaty prohibits states from exploiting the moon for commercial gains, including mining. It discusses the principle that the moon is to be regarded as belonging to all humanity, including the idea of sharing resources obtained there. The three major refusniks consider it too restrictive.