Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index keeps track of the issue worldwide. We offer excerpts from the report:

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 reveals a staggering number of countries are showing little to no improvement in tackling corruption. Our analysis also suggests that reducing big money in politics and promoting inclusive political decision-making are essential to curb corruption.

In the last year, anti-corruption movements across the globe gained momentum as millions of people joined together to speak out against corruption in their governments.

Protests from Latin America, North Africa and Eastern Europe to the Middle East and Central Asia made headlines as citizens marched in Santiago, Prague, Beirut, and a host of other cities to voice their frustrations in the streets. From fraud that occurs at the highest levels of government to petty bribery that blocks access to basic public services such as health care and education, citizens are fed up with corrupt leaders and institutions. This frustration fuels a growing lack of trust in government and further erodes public confidence in political leaders, elected officials and democracy.

The current state of corruption speaks to a need for greater political integrity in many countries. To have any chance of curbing corruption, governments must strengthen checks and balances, limit the influence of big money in politics and ensure broad input in political decision-making. Public policies and resources should not be determined by economic power or political influence, but by fair consultation and impartial budget allocation.

Recommendations

To end corruption and restore trust in politics, it is imperative to prevent opportunities for political corruption and to foster the integrity of political systems. Transparency International recommends the following.

Reinforce checks and balances: Governments must promote the separation of powers, strengthen judicial independence and preserve checks and balances.

Strengthen electoral integrity: For democracy to be effective against corruption, governments must ensure that elections are free and fair. Preventing and sanctioning vote-buying and misinformation campaigns are essential to rebuilding trust in government and ensuring that citizens can use their vote to punish corrupt politicians.

Empower citizens: Governments should protect civil liberties and political rights, including freedom of speech, expression and association. Governments should engage civil society and protect citizens, activists, whistleblowers and journalists in monitoring and exposing corruption.Control political financing: In order to prevent excessive money and influence in politics, governments should improve and properly enforce campaign finance regulations. Political parties should also disclose their sources of income, assets and loans, and governments should empower oversight agencies with stronger mandates and appropriate resources.

Regulate lobbying activities: Governments should promote open and meaningful access to decision-making and consult a wider range of groups, beyond well-resourced lobbyists and a few private interests. Lobbying activities should be public and easily accessible.

Manage conflicts of interest: Governments should reduce the risk of undue influence in policy-making by tightening controls over financial and other interests of government officials. Governments should also address “revolving doors,” establish cooling-off periods for former officials and ensure rules are properly enforced and sanctioned.

Tackle preferential treatment: Governments should create mechanisms to ensure that service-delivery and public-resource allocation are not driven by personal connections or are biased towards special interest groups at the expense of the overall public good.

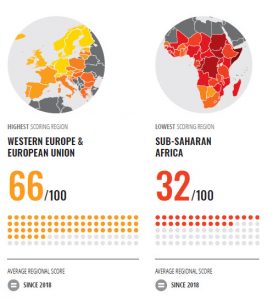

GLOBAL HIGHLIGHTS

This year’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) shows corruption is more pervasive in countries where big money can flow freely into electoral campaigns and where governments listen only to the voices of wealthy or well-connected individuals.

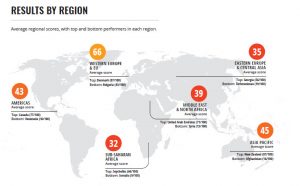

The index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, according to experts and business people. It uses a scale of zero to 100, where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean. More than two-thirds of countries score below 50 on this year’s CPI, with an average score of just 43. Similar to previous years, the data show that despite some progress, a majority of countries are still failing to tackle public-sector corruption effectively.

The top countries are New Zealand and Denmark, with scores of 87 each, followed by Finland (86), Singapore (85), Sweden (85) and Switzerland (85). The bottom countries are Somalia, South Sudan and Syria with scores of 9, 12 and 13, respectively. These countries are closely followed by Yemen (15), Venezuela (16), Sudan (16), Equatorial Guinea (16) and Afghanistan (16).

In the last eight years, only 22 countries significantly improved their CPI scores, including Greece, Guyana and Estonia. In the same period, 21 countries significantly decreased their scores, including Canada, Australia and Nicaragua. In the remaining 137 countries, the levels of corruption show little to no change.

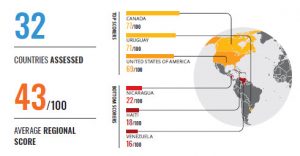

AMERICAS

With an average score of 43 for the fourth consecutive year, the Americas region fails to make significant progress in the fight against corruption.

While Canada is consistently a top performer, with a score of 77 out of 100, the country dropped four points since last year and seven points since 2012. At the bottom of the index, Venezuela scores 16, which is also one of the bottom five scores globally.

The region faces significant challenges from political leaders acting in their own self-interest at the expense of the citizens they serve. Specifically, political party financing and electoral integrity are big challenges.

For example, the Lava Jato investigation, or “Operation Car Wash,” which exposed corruption spanning at least 10 countries in Latin America, points to a surge in illegal political contributions or donations as part of one of the biggest corruption scandals in history.

Odebrecht, the Brazilian construction giant at the heart of the case, was convicted for paying US$1 billion in bribes over the past 15 years, including to political leaders in Brazil, Peru and Argentina during elections.

With scores of 22 and 29 respectively, Nicaragua and Mexico are significant decliners on the CPI since 2012. Although the recent Global Corruption Barometer — Latin America and the Caribbean13 highlights vote-buying and other corruption issues in Mexico, a recent anti-corruption reform, along with a new, legally autonomous attorney general’s office are positive changes.

In Nicaragua, social unrest and human rights violations are on the rise. Public services and consultative decision-making are sorely lacking in the country. With a score of 40, Guyana is a significant improver on the CPI since 2012. While there is still much work to do, the government is demonstrating political will to hold former politicians accountable for the misuse of state resources.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

United States

With a score of 69, the United States drops two points since last year to earn its lowest score on the CPI in eight years. This comes at a time when Americans’ trust in government is at an historic low of 17 per cent, according to the Pew Research Center.

The U.S. faces a wide range of challenges, from threats to its system of checks and balances and the ever-increasing influence of special interests in government, to the use of anonymous shell companies by criminals, corrupt individuals and even terrorists, to hide illicit activities.

While President [Donald] Trump campaigned on a promise of “draining the swamp” and making government work for more than just Washington insiders and political elites, a series of scandals, resignations and allegations of unethical behaviour suggest that the “pay-to-play” culture has only become more entrenched. In December 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives formally impeached Trump for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

Brazil

Corruption remains one of the biggest impediments to economic and social development in Brazil. With a score of 35, Brazil remains stagnated, with its lowest CPI score since 2012.

After the 2018 national elections, which were strongly influenced by an anti-corruption agenda, Brazil experienced a series of setbacks to its legal and institutional anti-corruption frameworks. The country also faced difficulties in advancing wide-ranging reforms to its political system.

Setbacks included a Supreme Court injunction that virtually paralyzed Brazil’s anti-money laundering system and an illegal inquiry that secretly targeted law- enforcement agents.

Ongoing challenges include growing political interference with anti-corruption institutions by President Jair Bolsonaro, and congressional approval of legislation that threatens the independence of law enforcement agents and the accountability of political parties

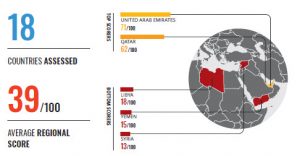

MIDDLE EAST AND

NORTH AFRICA

With the same average score of 39 as last year, there is little progress in improving control of corruption in the Middle East and North Africa region.

With a score of 71, the United Arab Emirates is the best regional performer, followed by Qatar (62). At the bottom of the region, Syria scores 13, followed by Yemen with a score of 15. Both countries are significant decliners on the CPI, with Yemen dropping eight points since 2012 and Syria dropping 13 points during the same period.

The region faces significant corruption challenges that highlight a lack of political integrity. According to our recent report, Global Corruption Barometer — Middle East and North Africa, nearly one in two people in Lebanon is offered bribes in exchange for their votes, while more than one in four receives threats if they don’t vote a certain way.

In a region where fair and democratic elections are the exception, state capture is commonplace. Powerful individuals routinely divert public funds to their own pockets at the expense of ordinary citizens. Separation of powers is another challenge: independent judiciaries with the potential to act as a check on the executive branch are rare or non-existent.

To improve citizens’ trust in government, countries must build transparent and accountable institutions and prosecute wrongdoing. They should also hold free and fair elections and allow for citizen engagement and participation in decision-making.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

Tunisia

With a score of 43, Tunisia remains at a standstill on the CPI despite advances in anti-corruption legislation over the past five years. Recent laws to protect whistleblowers and improve access to information, combined with stronger social accountability and space for civil society, are important steps, but they are not enough.

For anti-corruption laws to be effective, decrees and implementing orders from the executive branch are needed. In addition, financial and human resources are vital to strengthen the country’s anti-corruption commission and increase its independence.

To date, few political leaders have been prosecuted for corruption, and recovery of stolen assets is slow. An independent judiciary is another major challenge. While the recent establishment of a judiciary council is encouraging, the council is not yet fully operational and still lacks total independence from the legislative branch.

Saudi Arabia

With a score of 53, Saudi Arabia improved by four points since last year. However, its score does not reflect the myriad problems in the country, including a dismal human rights record and severe restrictions on journalists, political activists and other citizens.

In 2017, the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman carried out an ”anti-corruption” purge as part of his reform of the country.

Despite government claims of recovering approximately US$106 billion of stolen assets, there was no due process, transparent investigation or fair and free trial for suspects.

This year, Saudi Arabia takes on the presidency of the G20. As it assumes this leadership role, the country must end its crackdown on civil liberties and strengthen further checks on the executive branch to foster transparency and accountability.

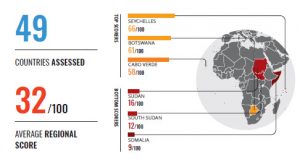

SUB-SAHARAN

AFRICA

As the lowest-scoring region on the CPI, with an average of 32, Sub-Saharan Africa’s performance paints a bleak picture of inaction against corruption.

With a score of 66, the Seychelles earns the highest mark in the region, followed by Botswana (61), Cabo Verde (58), Rwanda (53) and Mauritius (52). At the bottom of the index are Somalia (9), South Sudan (12), Sudan (16) and Equatorial Guinea (16).

Significant improvers since 2012, Cote d’Ivoire (35) and Senegal (45) still have much work to do. The political will demonstrated by the leaders of both countries, which saw a number of key legal, policy and institutional reforms implemented in their early days in office, has been on a backslide since 2016.

Since 2012, several countries, including Congo (19), Liberia (28), Madagascar (24) and Malawi (31) have significantly declined on the CPI. Congo has been the subject of repeated reports of money laundering and embezzlement of public funds by the country’s political elite with no action taken by national authorities.

In Madagascar, despite a 2018 constitutional court ruling against electoral amendments favouring the incumbent president and cited as unconstitutional, judicial independence remains a concern. More recently, the national anti-corruption agency began legal action against more than half of the country’s parliamentarians, who stand accused of taking bribes.

Money is used to win elections, consolidate power and further personal interests. Although the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combatting Corruption has provisions to prevent corruption and encourage transparency in campaign financing, implementation is weak.

SIGNIFICANT DECLINERS

Since 2012, several countries, including Congo (19), Liberia (28), Madagascar (24) and Malawi (31) have significantly declined on the CPI. Congo has been the subject of repeated reports of money laundering and embezzlement of public funds by the country’s political elite with no action taken by national authorities.

In Madagascar, despite a 2018 constitutional court ruling against electoral amendments favouring the incumbent president and cited as unconstitutional, judicial independence remains a concern. More recently, the national anti-corruption agency began legal action against more than half of the country’s parliamentarians, who stand accused of taking bribes.

LOW SCORERS

Towards the bottom of the index, with a score of 18, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) faces several corruption challenges. According to our recent report, Global Corruption Barometer — Africa, political integrity among government officials is extremely low, with 79 per cent of DRC citizens believing that all or most parliamentarians are involved in corruption.

With the lowest score on the CPI, Somalia is not only one of the world’s most corrupt countries, but it is also, “one of the world’s most protracted cases of statelessness” according to the 2016 Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index. State fragility and poor rule of law have left gaping holes for graft to flourish from petty bribery to high-level political corruption.

Tackling corruption in the context of fragile states presents unique challenges, as fragility is both a cause and an effect of any downward trends in development. With plans under way in Somalia to hold the first “one person-one vote” election in 50 years, it is critical that political accountability structures to facilitate anti-corruption mechanisms are put in place.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

Angola

Following four decades of authoritarian rule, Angola (26) jumped seven points in this year’s CPI, making it a significant improver. However, given its overall low score, the country is still well below the global average of 43. Isabel Dos Santos, the former president’s daughter, who is also known as “Africa’s richest woman,” was fired from her job as head of the state oil and gas firm, Sonangol, months after President João Lourenço’s election. In December 2019, as investigations into corruption allegations progressed, an Angolan court ordered a freeze of Dos Santos’s assets.

Although the country has recovered US$5 billion in stolen assets, more needs to be done to strengthen integrity and promote transparency in accounting for oil revenue.

Ghana

Known as a beacon of democracy in West Africa, Ghana dropped seven points on the CPI since 2014, moving from 48 in 2014 to 41 in 2019. Revelations of bribery in Ghana’s high court in 2015 and the murder of investigative journalist Ahmed Hussein-Suale in early 2019 cast serious doubts on the country’s anti-corruption efforts. Despite these developments, there is hope for change. In 2017, the office of special prosecutor was established, which has the power to investigate and prosecute cases of corruption. In 2019, a right to information bill was also passed. These efforts, combined with the enhanced performance of the auditor general’s office, offer hope for improvement.

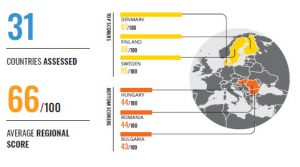

WESTERN EUROPE

AND THE EUROPEAN UNION

Fourteen of the top 20 countries in this year’s CPI are from Western Europe and the European Union (EU), including nine countries from the EU alone.

Despite being the best performing region, with an average score of 66 out of 100, Western Europe and the EU are not immune to corruption. With 87 points, Denmark is the highest-scoring country in the region, followed by Finland (86), Sweden (85) and Switzerland (85).

At the bottom of the region are Bulgaria (43), Romania (44) and Hungary (44). With a score of 53, Italy increased by 11 points since 2012 while Greece (48) increased by 12 points during the same period. Both countries experienced concrete improvements, including legislative progress in Italy with the passage of anti-corruption laws and the creation of an anti-corruption agency in both countries.

Most post-communist EU member states are struggling to address corruption effectively. Several countries, including Hungary, Poland and Romania, have taken steps to undermine judicial independence, which weakens their ability to prosecute cases of high-level corruption. In the Czech Republic (56), recent scandals involving the prime minister and his efforts to obtain public money through EU subsidies for his company highlight a startling lack of political integrity. The scandals also point to an insufficient level of transparency in political campaign financing. Issues of conflict of interest, abuse of state resources for electoral purposes, insufficient disclosure of political party and campaign financing, and a lack of media independence are prevalent and should take priority for national governments and the EU.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

Malta

With a score of 54, Malta is a significant decliner on the CPI, dropping six points since 2015. Given the “pair of political machines [that] have [for decades] operated with impunity on the island” it’s no wonder that two years after the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed while reporting on corruption, the country is still mired in corruption. Despite calls from Maltese citizens, Caruana Galizia’s family and the international community to solve the case, the government dragged its feet in the judicial procedures. Several scandals involving the Panama Papers, the collapse of a Maltese bank and the “golden visa” scheme that sells Maltese citizenship to wealthy overseas investors may also contribute to Malta’s decline on the CPI.

Estonia

For the past decade, Estonia (74) has seen a stable rise on the CPI. A significant improver, the country increased its score by 10 points since 2012. A comprehensive legislative framework, independent institutions and effective online tools make it possible to reduce petty corruption and make political party financing open and transparent. There is a need, however, to legally define and regulate lobbying to prevent and detect undue influence on policy-making.

Although private sector corruption is not captured on the CPI, recent money laundering scandals involving the Estonian branch of Danske Bank demonstrate a greater need for integrity and accountability in the banking and business sectors. The scandal also highlights a need for better and stronger EU-wide anti-money laundering supervision.

ASIA PACIFIC

A regional average of 45, after many consecutive years of an average score of 44, illustrates general stagnation across the Asia Pacific.

Despite the presence of high performers like New Zealand (87), Singapore (85), Australia (77), Hong Kong (76) and Japan (73), the region hasn’t witnessed substantial progress in anti-corruption efforts or results. In addition, low performers like Afghanistan (16), North Korea (17) and Cambodia (20) continue to highlight serious challenges in the region.

While often seen as an engine of the global economy, in terms of political integrity and governance, the region performs only marginally better than the global average. Many countries see economic openness as a way forward, however governments across the region, from China to Cambodia to Vietnam, continue to restrict participation in public affairs, silence dissenting voices and keep decision-making out of public scrutiny.

Given these issues, it comes as no surprise that vibrant economic powers such as China (41), Indonesia (40), Vietnam (37), the Philippines (34) and others continue to struggle to tackle corruption.

Even in democracies such as Australia and India, unfair and opaque political financing and undue influence in decision-making and lobbying by powerful corporate interest groups result in stagnation or decline in control of corruption.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

Indonesia

With a score of 40, Indonesia improves by two points on the CPI. A promising emerging economy is coupled with repression of civil society and weak oversight institutions. The independence and effectiveness of Indonesia’s anti-corruption commission, the KPK, is currently being thwarted by the government.

The Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK), is seen as a symbol of progress and modernization, but is undergoing a loss of autonomy and power. Paradoxically, this contradicts the government’s aspirations and President Joko Widodo’s own agenda, which prioritizes foreign investment and a booming economy. With corruption issues in the limelight, Indonesia risks scaring off investors and slowing economic progress.

Papua New Guinea

With a score of 28, Papua New Guinea remains stagnant on the CPI. However, despite low performance on the CPI for years, recent anti-corruption developments are encouraging.

Following the removal of former prime minister Peter O’Neill, currently being investigated for alleged corruption, the government instituted structural changes and introduced new legislation to establish an Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC). Together, these small improvements give citizens a reason for optimism.

Under the current leadership of Prime Minister James Marape, the government should uphold its previous commitments, as well as its 20-year anti-corruption strategy established in 2012, and work to investigate and punish bribery, fraud, conflicts of interest, nepotism and other corrupt acts.

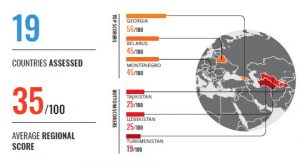

EASTERN EUROPE &

CENTRAL ASIA

Eastern Europe and Central Asia is the second-lowest performing region on the CPI, with an average score of 35.

Across the region, countries experience limited separation of powers, abuse of state resources for electoral purposes, opaque political party financing and conflicts of interest.

Only three countries score above the global average: Georgia (56), Belarus (45) and Montenegro (45).

At the bottom of the region are Turkmenistan (19), Uzbekistan (25) and Tajikistan (25).

Strong political influence over oversight institutions, insufficient judicial independence and limited press freedoms serve to create an over-concentration of power in many countries across the region. Despite aspirations to join the European Union, the scores in six Western Balkan countries and Turkey have not improved.

Turkey (39) declined significantly by 10 points since 2012, while Bosnia and Herzegovina (36) declined by six points in the same period. A lack of political will and a decline in implementation of laws and regulations are real challenges. Since 2012, Belarus (45), Kyrgyzstan (30) and Uzbekistan (25) have significantly improved on the CPI. However, these three post-Soviet states continue to experience state capture and a failure to preserve checks and balances. While Uzbekistan has loosened some media restrictions, it still remains one of the most authoritarian regimes worldwide.

State capture and the concentration of power in private hands remain a major stumbling block in the region. Corruption can only be addressed effectively if political leaders prioritize public interests and set an example for transparency.

COUNTRIES TO WATCH

Armenia

With a score of 42, Armenia improves by seven points since last year. Following the revolution in 2018 and the formation of a new parliament, the country has demonstrated promising developments in advancing anti-corruption policy reforms.

Despite these improvements, conflicts of interests and non-transparent and unaccountable public operations remain impediments to ending corruption in the country. While improving political integrity will take time and resources, increasing public trust in law enforcement and the judiciary are critical first steps in ensuring appropriate checks and balances and improving anti-corruption efforts.

Kosovo

With a score of 36, Kosovo is experiencing a shift in parliamentary power that could offer an opportunity for change. After years of criticizing the government and international community in Kosovo for their failure to address corruption, the Self-Determination (Vetevendosje) Party, which recently won a majority of parliamentary seats, has a chance to demonstrate its commitment to combating corruption. During the election campaign, the party was one of a few that responded to requests to disclose campaign costs.

However, it remains to be seen if a new government will live up to a higher standard of political integrity. It can do so by abandoning the usual practice of political appointments in state-owned enterprises and by establishing a strong legal obligation for financial disclosure by political parties.

TROUBLE AT THE TOP

Top scoring countries on the CPI like Denmark, Switzerland and Iceland are not immune to corruption. While the CPI shows these public sectors to be among the cleanest in the world, corruption still exists, particularly in cases of money laundering and other private-sector corruption.

The Nordic economies stand out as leaders on the CPI, with Denmark (87), Finland (86), Sweden (85), Norway (84) and Iceland (78) taking five of the top 11 places. However, integrity at home does not always translate into integrity abroad, and multiple scandals in 2019 demonstrated that trans-national corruption is often facilitated, enabled and perpetuated by seemingly clean Nordic countries.

Despite some high-profile fines and prosecutions, our research shows that enforcement of foreign bribery laws among OECD countries is shockingly low. The outsized roles that some companies play in their national economies give them political support that too often triumphs over real accountability. Some banks and businesses aren’t just too big to fail — they’re also too powerful to pay. Anti-money laundering supervision and sanctions for breaches are often disjointed and ineffective.

The CPI highlights where stronger anti-corruption efforts are needed across the globe. It emphasizes where businesses should show the greatest responsibility to promote integrity and accountability, and where governments must eliminate undue influence from private interests that can have a devastating impact on sustainable development.

THE FISHROT FILES

In November, the Fishrot Files investigation revealed that Samherji, one of Iceland’s largest fishing conglomerates, allegedly bribed government officials in Namibia (52) for rights to massive fishing quotas. The company established shell companies in tax havens such as the UAE (71), Mauritius (52), Cyprus (58) and the Marshall Islands, some of which were allegedly used to launder the proceeds of corrupt deals. Many of the funds ended up in accounts of a Norwegian state-owned bank, DNB.

TELECOM BRIBERY

Last year, Swedish telecoms giant, Ericsson, agreed to pay more than US$1 billion to settle a foreign bribery case over its 16-year cash-for contracts campaign in China (41), Djibouti (30), Kuwait (40), Indonesia (40) and Vietnam (37). This is the second largest fine paid to U.S. authorities.

DANSKE BANK SCANDAL

Following the money laundering scandal at Danske Bank, the largest bank in Denmark (87), major banks such as Swedbank in Sweden (85) and Deutsche Bank in Germany (80), were reportedly investigated in 2019 for their role in handling suspicious payments from high-risk non-resident clients, mostly from Russia (28), through Estonia (74).

THE SNC-LAVALIN AFFAIR

In Canada (77), which drops four points since last year, a former executive of construction company SNC-Lavalin was convicted in December over bribes the company paid in Libya (18).