Hebron, though only a deserted coastal settlement in northern Labrador, is a uniquely powerful National Historic Site of Canada.

And, it may hold double interest to its visitors in these early days of the COVID-19 virus’ spread around the world.

Members of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, representing 180,000 Inuit in Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Russia, are at much higher risk because they not only lack running water and sewage disposal, but also already have a high incidence of tuberculosis and respiratory infections. In March, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledged the deficiencies from “housing to health care” in a meeting with the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee.

An estimated 70 per cent of Hebron’s Inuit residents died during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, which is believed to have killed 30 per cent of Labrador’s 1,200 Inuit. So terrible was the toll that bodies had to be piled up inside buildings. The large graveyard behind the settlement building is testament to the many Inuit who died, and are mostly in unmarked graves.

The flu infected about one-third of the world’s population, killing between 20 million to 50 million people, or between 3 and 5 per cent of those afflicted. (The Spanish flu is a geographic misnomer. Coming as it did in the final year of the First World War, the Allies had suppressed reports of its rampaging infection rate, but neutral Spain had no such censorship. With most news emanating from that country, its name has been unfairly attached to the pandemic.)

A vivid recounting We All Expected to Die: Spanish Influenza in Labrador, 1918-1919, by journalist and documentary filmmaker Anne Budgell, describes the deadly outcome of the Hebron community’s enthusiastic visit to the Moravian supply ship, Harmony, with its single sick and highly contagious crew member aboard.

It may be the closest point of comparison to the now-feared infection rate of the China-originating and news-suppressed outbreak of the COVID-19 virus.

“Hebron” resonates powerfully and symbolically in Labrador, in the same way “relocation” and “The Scoop” of Aboriginal children resonate. It carries a sharp lesson that Indigenous peoples have learned in the face of enforced Western culture and government practices.

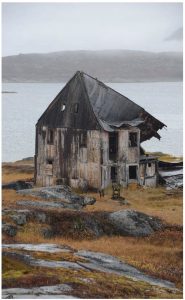

The Moravian Missionaries, who also built other settlements along the coast, operated in Hebron from 1831 to 1959, trading, providing medical and educational services and converting many Inuit to Christianity. Their main building still stands and is undergoing renovation. Others long ago collapsed.

The original German-born missionaries who came to save body and soul were a mixed blessing of improvements in the lives of the Inuit. Along with their lifesaving medical work, the Moravians exerted cultural control. Inuit were to speak English, laughter was unwelcome and the ancient use of facial tattoos depicting a woman’s marital status was forbidden.

Here, the Moravians crossed paths with a British missionary physician, Harry Locke Paddon, who sailed to Labrador in 1912, married Mina Gilchrist, a nurse from New Brunswick, and, for years, they treated Labrador residents. A member of the International Grenfell Association, he travelled, sometimes for weeks, by dogsled to care for the residents of Labrador’s many small communities.

And, noting the high childbirth mortality rate, he even cultivated a garden and advocated the consumption of vegetables, berries, cod liver oil and brown flour to combat scurvy, rickets and malnutrition.

Women were often unable to deliver babies through hips weakened and deformed by rickets caused by lack of Vitamin D.

Labrador-born William Anthony “Tony” Paddon (1914–1995) followed in his father’s footsteps as a Canadian surgeon who married nurse Sheila Fortescue. He later became the only Labradorian lieutenant-governor of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Eventually, after years of dedicated work, the Moravian Mission, the Newfoundland government and the International Grenfell Association made a decision. Among other hardships that they noted, the trio agreed it would be impossible to serve the spread-out Inuit communities with adequate medical care and housing available to the modern state that Newfoundland and Labrador was becoming.

They ultimately set on a course of action that tore apart the lives and cultures built over thousands of years — a compound fracture that continues into today’s second and third generations.

The Inuit (not consulted and living their traditional hunting, fishing and trapping lives) were to receive education, housing and medical services. It included treatment for high rates of tuberculosis and other Western diseases that overpowered the immune systems of Indigenous people, such as influenza, scarlet fever, smallpox and measles, and decimated their populations.

The drive to consolidate Labrador’s isolated coastal communities for convenience and to ensure their survival in the march of Western civilization and, in some minds, to “civilize” the Inuit, came down to two words: Forced relocation.

According to one report, from 1953 to 1965, 7,500 people were relocated from 115 communities. The pull-out by the Moravian Church and the closing of the store and withdrawal of the Grenfell nurse hastened relocation from Hebron, and, further south, Nutak in 1956 and 1959, respectively.

Some residents had to shoot their own sled dogs — a particularly bitter and painful memory.

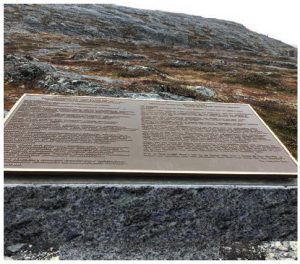

Newfoundland premier Danny Williams apologized in 2005 and each still-living person who was forced to move received a cheque for $63,000. In 2009, he commemorated three bronze plaques, one listing the names of all the exiled residents and the second recording the formal apology by the government. The third was the Labrador Inuits’ response, which read, in part:

“We accept your apology — for ourselves, our ancestors and our descendants. We have waited over 45 painful years for this apology, and we accept it because we want the pain and the hurting to stop. Hearing your apology helps us to move on.… We forgive you.”

A parallel memorial event was held in Nutak in 2012.

The relocation was traumatic — it separated family members and friends who met further disappointments. Lacking promised housing, they were also dropped into unfamiliar territory whose residents had their own hunting and fishing territories. Poverty and despair overtook many.

— Donna Jacobs