Should politics be civil in the age of Trump and Twitter? Many Canadians think so. Canadians applauded when Conservative leadership candidate Peter MacKay walked back a tweet that had been issued by his leadership team poking fun at Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s yoga habit with a caption saying that “while running for leader of the Liberal Party, Trudeau’s campaign expensed $876.95 in yoga sessions and spa bills for Justin Trudeau. Liberals can’t be trusted.”

Admittedly, this was pretty mild stuff compared to what normally gets posted online. Name calling and ad hominem insults have become the norm in many Western democracies. For example, the online British journal, Conversation, criticized British parliamentarians for having “gloated, jeered, heckled and booed…[and] indulged in gleeful laughter, smug condescension and personal attacks” in the Brexit campaign. Conversation went on to point out that “while providing enormous entertainment value to those not directly affected by Brexit, to most of the British public, the events [were] a tragedy.” Or, consider the unfortunate case of former Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar, who was blasted by a deluge of abusive messages over his planned commemoration of the controversial Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) — messages that branded him a “fascist” and a “dirty traitor.”

When the sexting of Benjamin Griveaux, an associate of French President Emmanuel Macron and candidate for mayor of Paris, was leaked online, forcing him to pull out of the race, France’s political establishment cried foul. The actions of a Russian performance artist who had posted in flagrante delicto images of Griveaux were considered inappropriate and uncivil in a country where the private lives of politicians and public officials are generally considered off limits to the prying eyes of the media.

Lest Canadians think they are generally kind, polite and tolerant when it comes to their own political discourse, they might want to think again. As the CBC reported, in her ill-fated bid to secure re-election in 2017, Premier Kathleen Wynne was subjected to a torrent of sexist and homophobic remarks on social media. “The replies to Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne on Twitter are not for the faint of heart,” the CBC warned its readers. As the CBC further noted, Wynne is not the only female politician to be subjected to such abuse. Former NDP premier Rachel Notley, Conservative MP Michelle Rempel and Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwarth, have all been targets of highly offensive sexual abuse on social media.

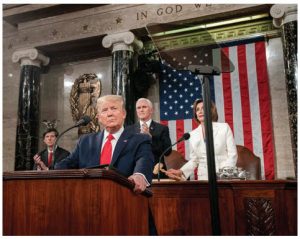

The uncivil State of the Union

The degeneration of political civility in the world’s leading democracy was on full display when Donald Trump, the 45th president of the United States, stepped up to the speaker’s rostrum in the House of Representatives to deliver his 4th State of the Union speech to the 116th Congress of the United States. He refused to follow customary protocol by shaking hands with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi before he delivered his address. It was a clear snub by a president who was deeply angered that Pelosi had allowed his impeachment trial to go forward.

Pelosi retaliated by refusing to introduce the president with the traditional words, “Members of Congress, I have the high privilege and distinct honour of presenting to you the president of the United States.” Instead, with barely concealed contempt, she snarled, “Members of Congress, the president of the United States.” And, at the conclusion of the president’s 78-minute speech — of which almost a third was consumed by repeated applause from the president’s Republican supporters — Pelosi, with a flair for the dramatic, shredded her copy of the president’s text in three bold strokes, throwing the remains onto her desk with feigned disgust.

It was a moment few would forget as it ricocheted on screens around the world.

What explains the loss of decorum and political civility in Western democracies? Some blame the rise of conservative populism while pointing a finger at Trump’s relentless reality TV theatrics on social media. But Republican and Democratic officeholders have played their own supporting roles in the loss of civility and decorum. President Richard Nixon used colourful language, not to mention “dirty tricks,” to vilify and attack his opponents, which led to his ultimate downfall in the Watergate scandal. President Lyndon Johnson was just as colourful and graphic in private conversation, but in public, like Nixon, he kept it clean. President Bill Clinton’s personal indiscretions with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, however, may have immunized the American public to the loss of decorum by subsequent presidential office holders, including Trump, but his successors George W. Bush and Barack Obama comported themselves with dignity and respect for the office of the president.

Political polarization propelled by fundamental perceptions of social and political “identity” in Western democracies is arguably a major factor in the decline in the quality and tone of political discourse aided, of course, by social media and the internet. As the then Washington Post’s Chris Cillizza, now at CNN, explained, American politics is now characterized by a political culture in which people view their adversaries as “idiots” or “even more malignant to our political dialogue, purposely ignorant with evil intent.” Cillizza cites a 2014 Pew Research Centre study, which showed that a sizable percentage of self-identified Republicans and Democrats (more than a quarter in each case) think the other party’s policies are so misguided “they aren’t just wrong, they endanger the nation’s well-being.” (The numbers are likely much higher today.)

He attributes this growing animus in the electorate to the growth of an increasingly partisan media on the left and right side of the spectrum. In addition, he observes, “ideological silos” have also formed, reinforced by the advent of social media and filter bubbles, where people see and hear what they want to see and hear.

Such polarizing trends are evident in other democracies as the debate over Brexit — now a done deal — in the United Kingdom attests. As British scholar Jonathan Wheatley explains, “The political divide over the issue of Brexit is now far more fundamental than the long-standing divide between political parties. A recent British Social Attitudes survey showed that 40 per cent of voters claimed to be either a “very strong remainer” or a “very strong leaver,” while just 8 per cent said they were a “very strong” supporter of a political party.” Wheatley’s research shows that “the Brexit divide should not be seen merely as a conflict over one particular issue, but instead reflects a broader ‘values divide’ that encompasses a range of identity issues about Britain’s relationship with the outside world and ‘outsiders’ more generally. These issues include immigration, multiculturalism, the role of Islam, gay rights and even climate change.”

Is a return to civility likely?

Is there any prospect that this roaring tide of incivility will be reversed?

Former British prime minister Tony Blair has founded an Institute for Global Change in a bid to bridge the divide between left- and right-wing populism. Pope Francis has offered his own pleas for moderation while issuing a series of papal warnings about the dangers of populism as an “evil” that “ends badly.”

The anti-populists who urge moderation and civility in political discourse clearly have their work cut out for them.

When Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, who presided over Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate, appealed for civility when he reminded the House managers and those defending the president that they were “addressing the world’s greatest deliberative body” and that the Senate had “earned that title because its members avoid speaking in a manner and using language that is not conducive to civil discourse,” he was criticized by some for ignoring the real and present danger vitriolic partisan politics poses to American democratic institutions.

“Roberts’ words,” journalist Steven Beschloss argues, “failed to take into account the backdrop [of the trial]: a deeply partisan and increasingly authoritarian political dynamic that has catapulted the country into a moment of crisis.”

If political insult is parried with political insult and fire is fought with fire, where will this all end? Fiery political revolutions have a nasty habit of consuming their own as the ultimate fate of Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre in the French Revolution reminds us.

But there is also a deeper, hidden danger. The Anglo-Irish statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke once argued that civility is essential to the functioning of a stable society and democratic political institutions. That is what Burke meant when he wrote about the importance of “chivalry” and “politesse” in politics, which he believed were threatened by the forces of revolution and mob rule that had swept through France with the overthrow of the monarchy. Burke believed the choice of words to address political opponents, and those with whom we strongly disagree, matters a great deal to a healthy and functioning democratic polity. Burke wrote, “Language is the eye of society, without it we could very ill signify our wants for our own relief, and by no means communicate our knowledge, for the amusement or amendment of our fellow creatures; and therefore without it the comforts and delights of life could not be enjoyed, no conveyance of learning, of chastisement, of praise, or solace, scarce virtue be practised, friendship subsist, nor religion taught and defended.” We must therefore always choose our words carefully.

Justice Roberts was right to urge civility and a careful, measured choice of words in the trial of an uncivil president. He may be a lonely voice, but his admonition should serve as a wider injunction to citizens in every democracy and not just the U.S. Basic decency and respect for others are the hallmarks of a civilized, democratic society. Demonization of political opponents is but a short step away from mob rule and demagoguery.

The COVID-19 global health crisis emergency, which exploded around the world in March, destroying lives, livelihood and economies, ironically may be injecting greater civility — at least temporarily — into political discourse as citizens and their leaders rally together to contain and defeat this scourge. When Ontario Premier Doug Ford was roundly criticized early in the crisis for urging Ontarians to go ahead with their spring break travel plans, he found an unlikely defender in Kathleen Wynne who said that Ford was simply trying to reassure a rattled public out of the “goodness of his heart.” Similarly, when Trump welcomed the new bipartisan spirit in the U.S. Congress to address the growing hardship of Americans in the unfolding COVID-19 crisis, it showed that the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government were willing to put paleolithic emotions aside for the greater national interest. As Canada’s distinguished columnist Rex Murphy wrote, “in times of anxiety, kindness is essential.” Justice Roberts was right to urge civility and a careful, measured choice of words in the trial of an uncivil president. But his admonition should serve as a wider injunction to citizens in every democracy at both the worst and the best of times.

Fen Osler Hampson is Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University. His newest book is Braver Canada: Shaping Our Destiny in a Precarious World (with Derek H. Burney.)