Kleptocracy destroys countries from within. Kleptocrats turn sometime democracies into criminal states that plunder national resources and national patrimonies, depriving citizens of their rights, their tax revenues and their ability to determine policy priorities. A cacophony of African states — Angola, the Comoros, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gabon, South Africa, South Sudan, Uganda and Zimbabwe — along with major places such as Russia, are or were recently captured by kleptocratic conspiracies of criminal intent.

A proposed new international anti-corruption court, conceivably located in Canada, could, by its very existence, deter the proliferation of the many kinds of corrupt practices that grow into kleptocracy and only very rarely can be curbed by the actions of domestic judicial systems. In most of the African countries listed, except South Africa, kleptocrats ruled or rule; appointed, promoted and paid the judges; and easily punished or dismissed the jurists who were disloyal. Even South Africa, with honest and independent courts, is still finding it hard to fully bring before the bar of justice ex-president Jacob Zuma and the cabal that helped him “capture” the advanced South African state fully.

Kleptocracy is a heightened version of corruption. The accepted definition of corruption is “the abuse of public office for private gain.” Or, some expand and simplify the definition to “the abuse of public trust.” Kleptocracy is the “shifting of a state’s riches into private hands.” Kleptocrats thus transfer into their own pockets wealth, for example, from copper in the DRC; oil in Angola, the other Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria; and diamonds and ferrochrome in Zimbabwe — all of which rightly belong to the citizens of those nations.

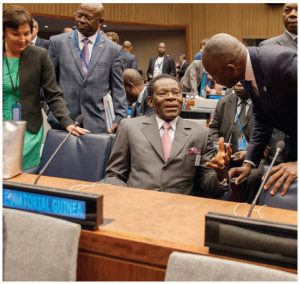

Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue is vice-president of Equatorial Guinea and son of Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, the wildly corrupt 40-year dictator of that country and the world’s longest-in-power president. When Mangue flew into Rio de Janeiro in 2018 on a private jet, supposedly to seek medical treatment, the Brazilian authorities quickly confiscated more than $1.5 million in cash he was carrying and a trove of monogrammed watches worth $15 million. Earlier, United States’ authorities, after court proceedings, had relieved Mangue of a $30-million house in Malibu, California, and a horde of Michael Jackson memorabilia, plus three expensive cars — all with wealth presumably looted from the people of his tiny West African principality. French authorities, not to be outdone, stripped Mangue of a townhouse in Paris, filled with art and housing Lamborghinis and Ferraris — all worth more than $100 million. Mangue is a kleptocrat who can hardly be tried for wholesale theft in a country that his father dominates and that they both use for personal enrichment. Additionally, in 2019, Swiss officials confiscated and auctioned off US$27 million worth of large “super” cars confiscated from Mangue. The millions were earmarked for social programs in Equatorial Guinea even though Mangue’s father runs the country and might be able to appropriate the US$27 million for his own purposes.

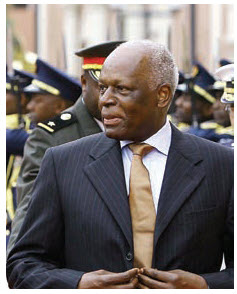

Another kleptocrat is Isobel dos Santos, favoured daughter of Eduardo dos Santos, ruler of Angola from 1979 to 2017. She is Africa’s wealthiest woman, worth an estimated $2 billion. Her father made her head of Sonangol, the state petroleum company, and gave her a controlling interest in the state diamond mining and selling concern. With that double boost to access to riches, Isobel dos Santos set up fake consulting companies in Malta and Dubai, shifted the millions of dollars that she amassed from questionable contracts and massive kickbacks into 450 fake offshore companies and European banks and demonstrated relatively effortlessly how successful kleptocrats operate. When a cache of 700,000 internal Angolan communiqués concerning the dos Santos scams were divulged to the press at the beginning of 2020, it was clear that Isobel dos Santos had operated above and beyond the law. Even Angolan courts, now loyal to a new national president, will have a hard time pursuing her (though her brother has been caught and is being tried for corruption) despite indicting her in late January for massive embezzlement and money-laundering offences.

Sudan’s former president Omar al-Bashir, another long-time African kleptocrat, was caught with US$113,000 in cash when soldiers once under his command raided his house and arrested him in 2019. He confessed that about US$90 million had been received from Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Sudanese officials have refused since 2004 to hand Bashir over to the ICC. Instead, a Sudanese court convicted him of corruption and sentenced him to jail for two years rather than turning him over to the International Criminal Court for trial on war crimes such as ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Now that he has been delegitimized by civil protests and military agreement, there have been public discussions about turning Bashir over to the ICC. But it was not yet clear at press time that Sudan’s military leaders will agree to do so.

Corruption is alive and well in Africa (and elsewhere in the world). The latest rankings of corruption prevalence in Africa and across the globe by Transparency International’s well-regarded Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) show that a dozen or so nations are judged a little corrupt, another dozen or so are less corrupt than their peers, but the majority of 180 countries rated in 2019 are abysmally corrupt. Most of the latter — the nations that fill the lowest ranks on the CPI — are African (along with Afghanistan, Haiti, North Korea, Syria, Turkmenistan and Yemen).

Indeed, as the accompanying map shows (see pages 56 and 57), African states occupy a preponderance of the places on the CPI list, downward from 70 (South Africa) to 179 (South Sudan) and 180 (Somalia). Kleptocrats control or were recently in control of most of these lower-rated states. Just recall president Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (1980 to 2017), president Mobuto Sese Seko of Zaire (now the DRC, 1965 to 1997), Eduardo dos Santos (father of Isobel), Omar al-Bashir of Sudan (leader from 1989 to 1993 and president from 1993 to 2019), the Obiangs, President Azali Assoumani of Comoros (1999 to present), the Bongo family in Gabon (president Omar Bongo 1967 to 2009, president Ali Bongo Ondimba, 2009 to present), and President Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of Congo (1979 to 1992, and 1997 to present, whose family paid cash recently for a luxury flat in Manhattan). The list goes on and on.

According to the latest CPI, the world’s least-corrupt countries in rank order are (and have nearly always been for decades) New Zealand and Denmark (tied for 1st place); Finland; Switzerland, Singapore, Sweden and Norway (the last four tied for 4th place); the Netherlands; Luxembourg; Germany; Iceland and (tied for 12th place) Canada, the U.K., Australia and Austria. The U.S. dropped from its mid-teens place in previous years to 23rd, just behind Uruguay. The least-corrupt African countries are the Seychelles and Botswana, at places 27 and 34 respectively. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the least-corrupt nations after Uruguay are Chile, St. Vincent and Costa Rica, in that order.

There are two kinds of corruption — grand (or venal) and petty (or lubricating). The latter is more easily seen and experienced. For example, I was in a car driven by a Zimbabwean when a police officer stopped us at a road block for driving without a compulsory reflective triangle. The triangle was in the car, in plain sight. No matter, the driver’s licence was confiscated and we were delayed until I ambled over to the constable, who was smirking at the other side of the road, and exchanged a crisp US$20 bill for the returned driver’s licence and permission to leave. Extortion is widespread when citizens confront bureaucrats in countries lacking rule of law.

Grand corruption is much more serious for citizens writ large, and for the fate of whole countries, even when individuals are less aware of their pockets being picked by officials of the state. Mugabe gave a contract for the construction of a new international airport to his nephew. Isobel dos Santos used her family position to purloin massively from the coffers of state companies. Zuma took kickbacks from foreign corporations to amass a small fortune. In the infamous Lava Jato case in Brazil, dozens of politicians profited from over-invoicing deals with Petrobras, the state petroleum monopoly. Multiple kickbacks brought politicians billions of dollars, much of which soon migrated illegally to Switzerland.

If and when an international anti-corruption court is created by treaty or UN General Assembly action (Colombia and Peru are trying to put the concept on the UN agenda in 2021), the court would be able to investigate corruption and money-laundering within states and across states. It would focus on pursuing those kleptocrats who could not be dealt with in domestic courts. Given talented forensic investigators and prosecutorial teams, it could do for corruption and kleptocracy what the effective special court for the former Yugoslavia did for Balkan war crimes when Justice Richard Goldstone of South Africa, followed by Justice Louise Arbour of Canada, were the chief prosecutors.

If a country that signs the covenant establishing the new court subsequently goes sour, then the legal agents of the court could (on petition from civil society in that nation) assume jurisdiction. If a kleptocrat’s country has not signed, jurisdiction could theoretically be assigned there by the Security Council (as it did for the ICC when Sudan’s Bashir was accused of ethnic cleansing and war crimes). The court could self-fund by confiscating billions of dollars from convicted kleptocrats.

Even absent uncontested jurisdiction, the mere existence of an international anti-corruption court would establish world order’s interest in reducing kleptocracy and corruption. Even if a convention establishing the court is adhered to at first only by a minority of the globe’s nations, the existence of the court would emphasize the world’s interest in limiting corruption and money laundering, and in pursuing major offenders aggressively. Even the remote possibility of being hauled in front of a global anti-corruption tribunal could deter and shame.

Mark L. Wolf, a distinguished Boston federal judge, the governments of Colombia and Peru and an organized group of two dozen international jurists and advocates (such as Justice Goldstone and Farid Rohani, a Vancouver entrepreneur) are promoting the idea of the court and attempting to mobilize broad-based support across continents. If the court comes into existence, with expert investigators and responsible judges, kleptocrats and political criminals in many of the world’s most poorly governed nations will find themselves at risk. At the same time — which is the point — Africa’s workers and farmers will reap greater prosperity, honest dealings and elevated standards of living.

Robert I. Rotberg is the founding director of Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Intrastate Conflict and he was Fulbright Distinguished Professor at Carleton and Waterloo universities. He authored The Corruption Cure (Princeton University Press, 2017) and will publish Anticorruption (MIT Press) this year. He is a member of the board of directors of Integrity Initiatives International, which advocates for an international anti-corruption court. Email rirotberg@gmail.com to reach him.