Autocrats, even democrats, always find it hard to give up office — especially in Africa. Likewise, no matter how often the African Union condemns military coups and sanctifies elected heads of state, soldiers oust politicians and refuse to stay in their barracks. Equally, there are authoritarians who abuse and assassinate their opponents, squelch those who favour widespread political participation and brutalize their citizens. Fortunately, these are not the only African stories: Across the 49 states of sub-Saharan Africa there are at least several whose leaders are widening the political arena to maximize inputs from constituents and are moderating the grip of dominant political party machines.

To have and to hold

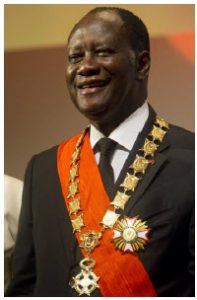

Alpha Condé of Guinea and Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivoire are the most recent heads of state to succumb to the incubus of third-term-itis. Despite constitutional provisions that limit presidents to two terms, Condé, 82, and Ouattara, 78, decided recently that their countries needed their continued leadership too urgently to leave office after just two terms of five years each.

In a referendum sponsored earlier this year by Condé, the people of Guinea voted overwhelmingly to permit him to run for a third term. After all, Condé regards himself as indispensable. His ability to rule Guinea well is little questioned by the strongman president nor by his ruling party or those who are provided with jobs and food by him and his party. But Condé has also run roughshod over his cowed opponents, locking up dozens of political prisoners in the last five years, and curtailing freedom of speech and the press. Massive protests erupted earlier this year over his ambitions to be a third-term president. They were beaten back by soldiers, with many fatalities. Condé’s anointment came after a fake election in October. Despite iron ore and bauxite deposits, Guinea’s per capita GDP in 2018 was only US $878. Corruption is rife. Condé has so far done little to improve the economic prospects of his 12 million citizens.

Ouattara is much more of a tolerant democrat. A northerner excluded from electoral politics by Laurent Gbagbo, his predecessor, Ouattara emerged from a bitter south-north civil war as president of the francophone republic, peacemaker and an organizer of successful economic development. His country grows cocoa in abundance, and coffee. Its GDP per capita is a healthy US $1,715. Cote d’Ivoire, with a population of 25 million, is much better placed in the 2020s than ever before, largely due to Ouattara’s sensitive leadership.

There are good arguments why someone of Ouattara’s demonstrated talents should continue to exercise those gifts in his country. But, in the manner of U.S. president George Washington, Ouattara decided earlier this year to stand down after two terms and make way for prime minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly. That plan was proceeding well until Coulibaly suddenly died in March. Rather than seek a replacement candidate, Ouattara and his ruling party opted to declare force majeure and put Ouattara forward as the presidential candidate in elections scheduled for late October. The party’s lame and specious argument is that since Ouattara’s first term as president began before the new constitution with its two-term limit was enacted in 2016, he has really only served one term, not two. There are two strong opposing candidates; Ivoirians will decide whether to stick with the president they know or choose an even earlier president or a disciple of Gbagbo’s. At least in this case, unlike in Guinea, there is choice.

When earlier democratically chosen presidents of Malawi, Senegal and Zambia tried to hang on beyond their allotted two terms they were rudely rebuked by their constituents. But Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, Idriss Deby in Chad and Isaias Afwerki in Eritrea have established themselves as presidents for life (in a manner pioneered decades ago by Kamuzu Banda in Malawi, Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia and Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe). They cripple potential dissidents and opposing political movements by any and all forceful means, shutting down dissenters and rounding up all manner of opponents.

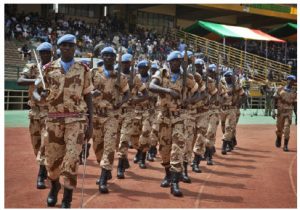

The coup in Mali

In August, after weeks of citizen protest in the urban centres of southwestern Mali, a military junta moved President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, 75, out of the presidential palace and sequestered him and other elected officials in its cantonment outside of Bamako. Protesters had clamoured for Keïta’s fall because of his administration’s perceived corruption and its inability to combat Islamist jihadi movements in the country’s northern desert and Sahel regions. The power of the Islamists, particularly those allied with the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), has grown in recent years despite the countervailing efforts of 5,000 French troops, a smaller contingent of Americans, French and American air cover and satellite intelligence, and the (mostly weak) efforts of the Malian army.

The African Union and the Economic Commission of West African States (ECOWAS) excoriated the coup-makers and demanded that electoral legitimacy be restored to Mali. In early September, the soldiers were saying, instead, that they will govern the country for two years, down from three, and then restore an electoral democracy. How they run it in the interim, and whether and when they give control back to civilians, will depend on how forceful ECOWAS can be, and how the soldiers initially administer a country still largely split between restive agriculturally minded southerners and northern pastoralists plagued by raids by Islamists.

Mali could indeed fall apart, or split in two. Today, and throughout the Keïta regime from 2013, only foreign legions kept it together. Moreover, within the last year, the Islamist rebels of ISIS and AQIM have gained strength, raiding much of Mali and sections of northern Burkina Faso and western Niger with unexpected impunity. Even experienced and well-led French forces, who know the terrain and have been curtailing the Islamists since 2013, cannot seem to extirpate either of the insurgent movements.

The modern autocrats

When President Paul Kagame of Rwanda kidnapped or lured (stories differ) Paul Rusesabagina, the celebrated hero of Hotel Rwanda, to Kigali in September, he was perpetuating a long-practised despotic pursuit of former colleagues or potential rivals who oppose his paramount chiefship of Rwanda; Kagame orchestrated an abandonment of presidential term limits and can (legally) serve as president (he began in 2005) until 2034. Kagame says Rusesabagina will get a fair trial for treason in Rwanda, a country where judges jump to Kagame’s wishes.

This is hardly the first time that Kagame, who tightly controls an otherwise well-administered country that is growing well economically and has a low incidence of COVID-19, has taken a vociferous opponent out of circulation. He had his people strangle Patrick Karegeya, a former Rwandan spy chief, in a Johannesburg hotel room in 2013. He sponsored the assassination of Seth Sendashonga, sometime minister of interior, in Nairobi in 1998. They were both former colleagues who had fled Rwanda to escape Kagame’s iron fist. Earlier this year, a prominent singer who opposed Kagame was found dead in his prison cell, supposedly by suicide. There is no free press or free expression of dissenting ideas in Rwanda.

Another democratically elected leader, President John Magufuli of Tanzania, turned from ruling on behalf of his 75 million people to ruling largely for himself. Magufuli is up for re-election in October, and potential opponents and others who criticize his rule have been locked up or eliminated. Magufuli has also managed arbitrarily to take over the operating mechanisms of the long dominant Chama Cha Mapinduzi (Revolution) party and to neuter opponents within the party as well as the nation. Magufuli has denied the existence of the coronavirus in Tanzania, and refused since April to divulge numbers of deaths.

One more example of despotism is President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s regime in hapless Zimbabwe. Taking over from dictator Robert Mugabe in 2017, Mnangagwa, a former intelligence chief with military support, promised a return to democracy and sensible economic policies. Instead, in September, inflation was running at 800 per cent per annum, the supposed Zimbabwe dollar was worth a fraction of a real U.S. dollar, supermarket shelves were bare and famine was spreading rapidly over large swathes of Zimbabwe (and Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia). A leading journalist who uncovered corruption by the health ministry in the distribution of coronavirus supplies was promptly jailed without a hearing for six weeks, being finally released on bail in September, pending trial. Another 20 or so prominent members of opposition parties still languish in detention.

The good news

In contrast to these backslidings among some of the key leaders in sub-Saharan Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa (whom we profiled in Diplomat in Summer 2018) has increased his popular appeal by deftly taking an appropriately strict line regarding the coronavirus and by winning a major struggle within his own African National Congress (ANC) over corruption. In July and August, Ramaphosa managed to oust several figures blocking the ascendancy of his pro-democratic faction within the ANC, which rules South Africa through its parliamentary majority. Many of those who lost their positions within the party were accused of corruption, as well as impeding Ramaphosa’s attempts to make the ANC more accountable and transparent. In September, as well, former president Jacob Zuma went on trial for massive corruption after long delays.

South Africa has suffered from the coronavirus more than most other sub-Saharan nations. Nearly 709,000 people have tested positive and, by mid-October, 18,492 had died in the pandemic. South Africa, under Ramaphosa, locked down earlier than any other African country and kept its people largely in quarantine, with masks, until July, thus limiting the spread of the deadly virus. Admittedly, South Africa has the best testing regime in Africa, and its numbers are partially a result of more tests and better reporting than elsewhere on the continent. In any event, Ramaphosa is widely credited with saving South Africans from even more fatalities and for producing a better result overall.

It is too early to know whether Lazarus Chakwera, president of Malawi, will have the same influence on COVID-19 results in his exceedingly poor country. Only elected president in June, he immediately imposed mask-wearing, physical distancing and many other sensible restrictions on his 19 million citizens. He took responsibility for curtailing the disease much more seriously than did his predecessor and most of his peers across Africa. He also made a series of appealing statements about the restoration of democratic practices in a nation that has suffered bouts of authoritarianism and corruption since the ouster of dictator Kamuzu Banda in 1994. He promised to declare his personal assets annually — a first for Malawi and most African nations — and to establish an independent anti-corruption bureau to investigate those who steal from the public. He even said he would introduce legislation to reduce the powers of the executive presidency.

In his forthright inaugural address in July, Chakwera said: “It is no secret that we have had one administration after another shifting its post to the next election, promising prosperity, but delivering poverty; promising nationalism, but delivering division; promising political tolerance, but delivering human rights abuses; promising good governance, but delivering corruption; promising institutional autonomy, but delivering state capture.” The nation had been left in “ruins,” so Chakwera pledged to get rid of the rubble of corruption and to replace lazy officials with energetic, conscientious ones. Government, he said, is service.

Other African presidents have entered office with equally positive messages and perhaps even the intention of being effective and accountable heads of state. If Chakwera can turn his promises into reality, Malawi will be the better for them, and Africa will have a rare victory for representative democracy.

Mixed messages

Ramaphosa and Chakwera, and the democratic series of presidents of Botswana and Ghana, may be exceptional outliers in sub-Saharan Africa, just as autocrats such as those in Equatorial Guinea, Niger, Gabon and the other countries discussed in this article, may be extreme examples of sub-Saharan Africa’s oscillation between high-handed denials of human rights and civil liberties and polities in which political participation and good governance are the norms. As, across the sub-continent, the middle class grows, as educational opportunity advances, and as mobile connections to the rest of the globe grow stronger, so the practices of the outliers should become more common everywhere. As Africa slowly emerges from the coronavirus pandemic, the middle class will want such improvements more and more.

Robert I. Rotberg is the founding director of Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Intrastate Conflict and was Fulbright Distinguished Professor at Carleton and Waterloo universities. He wrote The Corruption Cure (Princeton University Press, 2017) and published Anticorruption (MIT Press) and Things Come Together: Africans Achieving Greatness in the Twenty-first Century (Oxford University Press) in August.

rirotberg@gmail.com