Avid travellers may be longing for the return of footloose times, but the pandemic hasn’t nixed every opportunity to get out and about, even if some of our sojourns are now virtual. We’ve uncovered a clutch of COVID-safe travel ideas to keep you going until the spring. Some get you outside enjoying our Canadian winter, others prefer the appeal of a comfy chair with a favourite beverage at hand. Bon voyage!

Down by the water: Opened in 2016, the Sir John A. Macdonald Winter Trail runs west along the Ottawa River from the Canadian War Museum to Westboro Beach. Two groomed, 16-kilometre trails give cross-country skiers, snowshoers, hikers and snow bikers access to spaces normally little used in the winter, offer sometimes-breathtaking river vistas and include a chance to visit John Ceprano’s rock sculptures at Remic Rapids. Bring a snack and something to drink because there aren’t any facilities along the way. The trail is free, but donations help keep the grooming equipment going. Bonus: Along with parking at Westboro Beach, Champlain Park and the Canadian War Museum, three transit stations — Pimisi, Bayview/O-train and Dominion — border the trail. wintertrail.ca

Woodland gliding: You can head to the Rideau Canal or your local rink, but gliding through meadows, an orchard and a forest takes skating to a whole new level. RiverOak, a rural spot 30 minutes south of downtown Ottawa, has three kilometres of skating trails, designated hockey and ringette rinks as well as snowshoeing and hiking. You can use your hockey sticks on the trail, borrow from RiverOak’s modest supply of sticks and pucks if you forget your own and rent skates and a helmet for $12, although the rental stock is limited. The family operation includes an historic log barn lodge with a wood-burning stove (pandemic protocols are in place), its skating trails are partially lit at night (skaters should bring a headlamp) and dogs are welcome (but they need to be polite). Admission starts at $9, with youngsters under five getting in free. Open Wednesday-Sunday, depending on the weather. riveroak.ca

Virtual snooping: Financial pressures forced American humourist Mark Twain to abandon his 25-room dream home in Hartford, Conn., in 1891, but he always said it was where he had been happiest and most productive. With travel now in abeyance, we won’t be visiting the home anytime soon, but it is open virtually at marktwainhouse.org. The same goes for various other intriguing spots in the U.S., including Rowan Oak, the modified Greek Revival home of Nobel-winning novelist William Faulkner in Oxford, Miss., (www.rowanoak.com) and the house-studio of abstract expressionist painters Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner near East Hampton, N.Y. (savingplaces.org).

More virtual touring: For something completely different, have a peek inside Handel & Hendrix in London, England, where — albeit not contemporaneously — the classical and classic rock musicians once lived in side-by-side homes with just a wall between the two residences. The virtual tour of the Jimi Hendrix side, where the American-born guitar star lived from 1968 to 1969, is really just a mini-museum visit, but the George Frideric Handel home, where the German-born composer lived and worked for 36 years, is rewarding. Bonus: These virtual visits are generally free, although a donation is sometimes suggested. handelhendrix.org

Cordelia and company: Live theatres everywhere have been pretty much shut down for close to a year. But stages live on digitally, including the Stratford Festival. Stratfest@home (stratfordfestival.ca) gives you access to recorded versions of productions for $15 a month. The library includes The Tempest, with Christopher Plummer in an acclaimed performance as Prospero; an uproarious rock ‘n’ roll take on Twelfth Night, with the late Brian Dennehy as Sir Toby Belch; and King Lear, with Colm Feore as the fond and foolish old king in a production that’s at once tragic and tender, absurd and as richly rewarding as life itself.

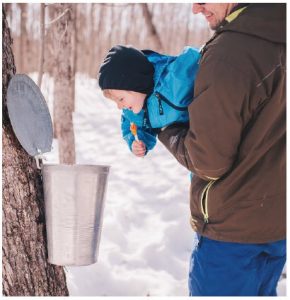

Sweet stuff: Other than Margaret Atwood and federal-provincial bickering, it’s hard to think of anything more Canadian — or at least central Canadian — than maple syrup. And there’s no shortage of the sweet, sticky stuff right here in Eastern Ontario. By late February, sap is usually running and producers are welcoming one and all to their sugar bushes to experience an age-old tradition. You’ll find sugar bushes (or “camps”) everywhere — from Proulx Maple & Berry Farm in east-end Ottawa (proulxfarm.com) to the old-timey Log Farm (thelogfarm.com) in Nepean, where sap is still collected in pails. Sugar bushes are especially abundant across Lanark County in the west (lanarkcountytourism.com). Unfortunately, the urban gem that was the sugar shack at Vanier Museopark was destroyed by fire last year and likely won’t reopen until 2022. Maple syrup is good for more than just pancakes, and, come springtime, you’ll find everything from maple butter to maple bacon doughnuts popping up around the Ottawa Valley. If you make the short trek to east-end Proulx Maple & Berry Farm, swing by Orleans Brewery (orleansbrewing.com) on the way home; its Maple Ale is made with Ottawa-area maple syrup.

Southward bound with a ghost: At a time when cross-border travel is largely off-limits, Tony Horwitz’s 2019 book. Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide is a dandy armchair equivalent. Horwitz, a Pulitzer-winning journalist with unbridled curiosity, journeyed through the southern U.S. before the 2016 presidential primaries, discovering an often-strange, economically hollowed-out place where fiction trumps fact, but humour and flickering hope live on. He modelled his journey on similar travels taken by Frederick Law Olmsted 160 years earlier. Olmsted, who eventually became a renowned landscape architect (New York City’s Central Park, Montreal’s Mount Royal Park), had taken a gig as an undercover correspondent in the Antebellum South for the emerging New York Times, and, like Horwitz, found the place fascinating. What Olmsted, whose presence accompanies Horwitz like a literary ghost, would have made of the south’s convulsed populace in the early 21st Century is anyone’s guess.

Changed — forever: Will Kyle, Winnie Burwash, Michiko Ishii — not exactly household names, but their stories are now a bit more widely known thanks to Forever Changed, a new exhibit at the Canadian War Museum. Like so many others during the Second World War, the lives of the three were permanently altered, whether by being brutally incarcerated as a prisoner of war, by sacrificing self and family to support the Canadian war effort, or, as a Japanese-Canadian teenager, by being forced to move 600 miles from home. Developed by the museum to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the war, the exhibit explores the personal wartime experiences of Canadians through stories and artifacts. Forever Changed runs until Sept. 6, with pandemic safety measures in place. warmuseum.ca 819-776-7000.

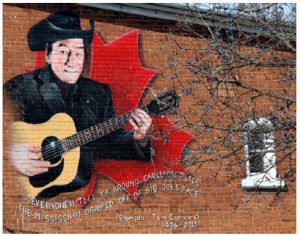

Marvellous murals: Stompin’ Tom Connors and First World War flying ace Roy Brown, who’s credited with shooting down the notorious Red Baron, may be dead, but they’re not entirely gone from Carleton Place. The town, about 35 minutes southwest of downtown Ottawa, is home to better than two dozen lively public murals of folks and events connected to Carleton Place. The Maritimes’ native son, Stompin’ Tom, for instance, loved to play at the 19th-Century Mississippi Hotel, now The Grand Hotel, and was instrumental in saving it from demolition. Some of the murals are “ghost” images — painted advertisements from long ago — such as the one for Chewing Plug Tobacco at 136 Bridge St. Other, newer ones commemorate historic events such as the Ballygiblin Riots of 1824, when Protestant settlers and Irish Catholic immigrants battled it out. You’ll find information on the murals, walking tours of the heritage downtown and more at

carletonplace.ca. And don’t forget to check out the tiny, perfect Carleton Place and Beckwith Heritage Museum (cpbheritagemuseum.com). While you’re there, try dinner at Black Tartan Kitchen, but book ahead as it’s a set menu during COVID.

Patrick Langston is an Ottawa writer who refuses to let COVID-19 limit his wandering ways.