Luring Paul Rusesabagina, the hero of Hotel Rwanda, to Kigali to be tried for “treason” for opposing the regime of President Paul Kagame is hardly the first “clever” Lukashenko-like entrapment of Rwandans who dare to criticize the tight-fisted manner in which Kagame has run his otherwise oft-praised African government. Much earlier, thugs sent by Kagame to South Africa enticed Patrick Karegeya, the autocrat’s one-time close friend and intelligence chief, into a Johannesburg hotel room, where he was brutally strangled. A journalistic critic was gunned down in 2011 in Uganda and Gen. Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, the former head of Rwanda’s armed forces, was wounded in 2010 during a botched murder attempt, also in Johannesburg. Attacks on dissidents roiled Stockholm, too, and Rwandan exiles were menaced in London, Russian style.

All of this “off the books” Mafia-reminiscent activity reflects murderously on the positive aspects of Kagame’s governmental enterprise in Rwanda, where, deep in the troubled heart of Africa, a strict autocracy masquerades successfully as a benevolent democracy. Rwanda is widely regarded as one of the best-run and best-governed countries of Africa in terms of service delivery. Yet Rwandans may not freely speak or assemble, or criticize their ruler. There is no free press or media. And it ranks close to the bottom on the global happiness index. Rwandans have traded (or been compelled to trade) basic freedoms in a Faustian way for compulsory conformity, low crime, low corruption and improved standards of living. In 1994, Rwanda’s GDP per capita was $205. It rose to $698 in 2014, to $765 in 2017 and to $819 in 2019. Possibly questionable statistical reporting aside, Rwanda’s GDP per capita has been growing at eight per cent in recent years, but those improvements may depend on fraudulent statistics.

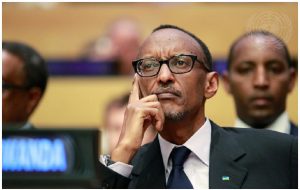

The man behind this compromised political arrangement is Kagame, a tall, stern, bullying, tight-lipped, heavy-lidded former American-trained intelligence officer and general who rescued Rwanda from the Hutu-led genocide of Tutsis in 1994 and has run Rwanda ever since. He also scrapped term limits, which means that he can legitimately remain Rwanda’s chief until at least 2034. Kagame, 64, tolerates dissent as little as he tolerates incompetence. Disloyalty, or opposition of the mildest kind, is often punished with death.

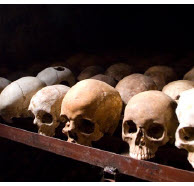

For all of these reasons, Kagame’s leadership in tiny Rwanda — a poor, congested African country half the size of Nova Scotia, with a swelling population of 13 million — provides a remarkable model that merits examination. Can a Platonic case be made for excellent results achieved by mostly dreadful means? Most of the world — as indicated by French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit of apology and reconciliation to Kagame and Rwanda for the 1994 Tutsi genocide — appropriately acclaims all that Rwanda has achieved under Kagame’s rule.

Much of the rest of Africa is less effective than Rwanda in reducing corruption, improving educational opportunities, upgrading public health facilities, gradually boosting GDP per capita, despite few natural resources, and providing the key political goods of safety and security.

Botswana, Mauritius, Namibia, Cape Verde and the Seychelles are all democratic nations that offer excellent outcomes to their citizens — what we term good governance. But three of those countries are island states and all are thinly populated, with fewer than three million inhabitants.

Three of the medium-sized African countries like Rwanda — Ghana, Malawi, and Senegal — are democratic, with high levels of governance performance. But according to the Corruption Perceptions Index, those places are more corrupt than Rwanda, and, Ghana excepted, their educational and health systems are no more advanced. South Africa rates better than Rwanda on the Index of African Governance (which I created.) But South Africa is wildly corrupt, whereas Rwanda has mostly eliminated corruption — a major burden lifted off the backs of Rwandans.

Unlike Botswanan presidents Seretse Khama, Ketumile Masire, Festus Mogae, and Mokgweetsi Masisi, Kagame can hardly claim to be a democrat, or even a consensus-building quasi-democrat. He is a naked authoritarian, but with substantial legitimacy as a genuine modernizer. What truly distinguishes him and his long reign as the head man of Rwanda is his close attention to improving the public good and the daily lives and outcomes of his densely-packed constituents.

Kagame responded to the horrific 1994 genocide in Rwanda by invading Rwanda at the head of a Tutsi army, in order to save as many remaining Tutsi lives as possible and to restore order in his country. Initially that meant imprisoning Hutu perpetrators of genocide or pursuing them and their ethnic compatriots into the nearby forests of the Congo. Subsequently, after Kagame had become vice-president, under a titular but powerless president, he focused on rebuilding, stabilizing and pacifying the desperate land that had lost at least 800,000 Tutsis and had seen 200,000 Hutus flee into the Congo, Burundi, Tanzania, and Uganda, and overseas. It also meant invading Zaire/the Congo twice, with great losses of life.

Kagame was no mere military leader with rudimentary ideas about organizing a reborn state and a responsible government. By 2000, when Kagame acceded to his nation’s presidency, he had articulated a vision for the emergence of war-damaged Rwanda as the Singapore of Africa. Rwanda lacks most of Singapore’s advantages: its perfectly positioned harbour, its geographical location at the crossroads of a good third of the globe’s commerce, its well-educated and advanced-skilled population and its greatly appreciated wealth per capita. Kagame nevertheless became determined — at least by 2005, if not before — to transform a very poor state with natural resources no more promising than shade-grown coffee (subject as it is to fluctuating world prices) into a well-functioning, promising, potentially middle-income jurisdiction in the heart of Equatorial Africa. Kagame has been favourably termed a “developmental patrimonialist, with considerable wealth derived from the mineral resources of the Congo.”

What Kagame presumably admired most about Singapore, the city-state that had been willed into modern existence by prime minister Lee Kuan Yew from 1965, was the careful and disciplined manner in which Lee had transformed a pirate-infested, gang-influenced, wildly corrupt, unruly port city into a thriving metropolis obedient to and willing to be compelled into conformity by the vision of Lee and the centralized way in which he and his government made decisions. They took those policy initiatives in the public interest, as defined by Lee, but were punctilious about not stealing from the people. Most of all, in Singapore, innovations such as shifting the Malay- and Chinese-speaking populace to English as a common language, the compulsory mixing of ethnic groups in highrise housing estates (to prohibit ghettos and ensure comity) and the introduction of air conditioning throughout the city, had a modernizing purpose. Lee’s government delivered progress, as enunciated from above, but also gave the city-state the stability, the rule of law, an emphasis on education, attention to medical services and the prosperity that attracted international investment and soon increased the per capita GDP of its citizens many times over. In 1965, that number was US $250 per capita and it has grown to $85,000 per capita today (numbers not adjusted for inflation.)

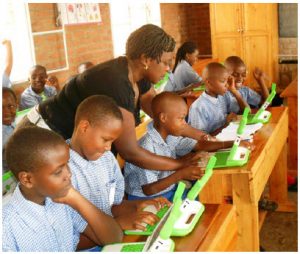

Kagame’s goal, since about 2005, has been to bring first-world educational opportunities to Rwanda, along with major improvements in life expectancies and other medical outcomes. Following a Brazilian model, Kagame pioneered cash transfers to the poorest in the country. He also promoted major infrastructural improvements. Non-Rwandans have been assisted in their efforts to upgrade health care in rural areas. Pioneering technological initiatives include drone deliveries of blood plasma to rural clinics. From 2005 to 2017, Rwanda experienced falling rates of maternal and infant mortality. Educationally, primary school persistence or completion rates have climbed from low levels to 57 percent in 2017. Life expectancy rose remarkably, from 48 in 2000 to 69 in 2020.

Kagame has thus performed as a strong leader across several dimensions. He has also echoed Lee, and Botswana’s presidents, by greatly lowering crime rates in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city of 921,000. Newly professionalized police even pursue litterers, making Kigali a compulsorily pristine locale by the standards of African cities. Kagame and his city officials outlawed street vending and imprisoned persistent offenders, a unique curtailing of the informal sector that is otherwise unknown in Africa. Pascal Nyamulinda, the former mayor of Kigali and a Kagame appointee, asserts that Kagame’s laws “must be respected.” Moreover, a decision to stamp out informal “hawking” could stand as a central motif for Kagame’s regime: “If you have to choose between a mess and discipline,” the obedient mayor once said, “I will choose discipline.”

Kagame reduced what had been a casual epidemic of corruption throughout the country by preaching against its evils — there were billboards throughout Kigali forbidding such behaviour: “He Who Practises Corruption Destroys His Country” — mercilessly prosecuting alleged offenders; removing from office any corrupt elected or appointed public officials, even associates of the president; and — most of all — remaining untainted himself by accusations of improper enrichment. Even so, Rwanda is still perceived as more corrupt in Africa than Botswana, the Seychelles, and Cape Verde (and less corrupt than Namibia, Mauritius, South Africa and all of the other sub-Saharan African states.) Its rating by the Corruption Perceptions Index rose from 83rd place in 2005 to 49th place in 2020 — a remarkable jump in perceived probity and one unprecedented in Africa.

When Kagame’s great reform program had begun to accelerate after 2005, he copied former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili and significantly downsized the civil service, finding ghost workers and existing bureaucrats who were inefficient or deemed superfluous. Competitive tests were introduced for the first time to improve competency and make merit appointments. Rwanda has also raised civil service salaries consistently.

In order to improve Rwanda’s ratings by the World Bank’s Doing Business reports, Kagame reduced bureaucratic controls and the number of permits required to open commercial concerns. His government minimized regulatory burdens and red tape. His aim was to produce a more investor-friendly and Singapore-like corporate environment, but also to make it at least conceivable that isolated and remote Rwanda could boast some of the advantages that accrued to Singapore.

As a result of all of these and many other innovations and initiatives, not least the careful subordination of Rwanda’s peoples to the clear-minded edicts of its president, the country’s governance ratings have risen, its civil service is better motivated than others in its African neighbourhood, its peoples are relatively prosperous compared to past decades, and Kagame can assert that he has brought stability and improved living standards to his disciplined polity.

But Kagame’s version of good government comes with high doses of coercion. The instincts of his people are held very much in check by fear of the state, fear of informers and fear of breaking rules. Rwandans, enjoying their positive quality of government, nevertheless do so knowing that they have paid a price. Instead of freedom of expression, one kind of positive political good, they benefit from physical deliveries of medicine and blood plasma to remote regions of the country by drone aircraft. They have better schools, even if schoolchildren know that complaining about governmental edicts would be unwise. Nor would competing for political office without permission, or arguing policy too loudly with the president or his colleagues.

There is no question about who is the boss. As Stalin eliminated Trotsky in distant Mexico City, so Kagame pursues those who are either deemed disloyal, such as Karegeya and Kayumba, or persons such as Rusesabagina, whose prominence shades Kagame’s lustre. In late 2018, the government banned “humiliating” cartoons of politicians and officials.

Rwanda is tightly regimented, but Kagame would argue that his leadership abilities have produced more and better personal and national outcomes for his people than those supposed deficiencies would imply. Kagame also says his decision to rewrite constitutional prohibitions against becoming a virtual president for life was essential if Rwanda were to keep moving ahead on its developmental trajectory, and continue to provide good returns to its citizens. These are high-flown rationalizations, of course, but Kagame has nevertheless remained popular among his people. Like Lee, he has produced the returns he said he would produce.

As an uncompromising, if profoundly paranoid leader, Kagame’s tenure demonstrates the importance of an ambitious vision, the virtue of mobilizing behind such a vision, the importance of self-mastery in pursuing visionary objectives, the relevance of legitimacy and the personal integrity that supports legitimacy, and the attributes that flow from the construction of a national edifice and a nation of which its citizens can be proud.

All of these conquests, including Kagame’s esteem among opinion-makers across the globe, makes his avid, spiteful pursuit of opponents in distant hotel rooms, and the entrapment of someone such as Rusesabagina, who poses no real threat, hard to understand or accept except as a matter of personal venom.

Benevolent autocrats occasionally have their uses. But the cases of Botswana, Cape Verde, Mauritius, today’s Ghana and the new dispensations in South Africa and Malawi demonstrate that excellent qualities of government can be achieved in developing countries by fully democratic means, employing the usual political stratagems of consensus-building, compromise, accommodation, and — where necessary — healthy competition. They benefit less from fear, oppression, intimidation and killings.

Human and national development can best be realized in an environment of freedom and open dialogue.

Robert I. Rotberg is the founding director of Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Intrastate Conflict and was Fulbright Distinguished Professor at Carleton and Waterloo universities. He wrote The Corruption Cure (Princeton University Press, 2017) and published Anticorruption (MIT Press) and Things Come Together: Africans Achieving Greatness in the Twenty-first Century (Oxford University Press) in August.

rirotberg@gmail.com