The sword and the word: These terms respectively describe the power of the state to make and enforce laws and the power of religion to shape millions of believers. What separates the West from the rest of the world is the (theoretically) strict separation between state and religion. It’s a spirit that also infuses other Western institutions and ideas, including the diffusion of political power across separate but equal sources of authority with the rule of law governing them all, and the supremacy of empiricism over dogmatism.

As Heinrich August Winkler, author of the monumental four-volumed A History of the West, and others have argued, these characteristics have their roots — many ironically — in Christianity, itself combining the monotheism of Judaism with “pagan ideas” from antiquity.

Early Christians embraced an enduring universalism in opening their faith to all groups regardless of social status and previous religious beliefs and sharply distinguished between a worldly and heavenly sphere, to “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s,” to quote the Gospel of Mark, a perspective that earned them violent persecution by the Roman Empire.

Christianity, of course, eventually became the religion of the empire and its successors. And yet the tension between the sword and the word never ceased. Certainly it continued in Western Europe, the geographic centre of Christianity after the spread of Islam through Asia and North Africa between the middle of the 7th and the middle of the 15th centuries, but before the European colonization of the Americas and beyond.

This tension (exacerbated by sectarianism within Christianity) sparked the religious wars that roiled Europe following the Protestant Reformation, climaxing in the continental catastrophe of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48), which depopulated parts of continental Europe through war, famine and disease. But, as cynical as it might sound, this conflict also had positive consequences. It not only sparked the emergence of the modern nation-state, but also set the fuse on the slow but inevitable divorce of the political from the religious.

Prussia’s King Frederick the Great summarized this sentiment in the 18th Century when he told his subjects that they could prepare themselves for the afterlife in any way they pleased.

True, the European Enlightenment (with its anti-clerical spirit) also led to the anti-religious excess of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic period and ultimately the forced secularization of Eastern Europe during its Soviet period.

On the other hand, the 19th Century witnessed the ongoing perversion of Christianity in Western Europe in the form of colonialism abroad and stifling social policies at home, including the state-sanctioned oppression of religious minorities such as Europe’s Jewish population. Mixed with Social Darwinism, it set the stage for the Holocaust.

On the other hand, the 19th Century witnessed the ongoing perversion of Christianity in Western Europe in the form of colonialism abroad and stifling social policies at home, including the state-sanctioned oppression of religious minorities such as Europe’s Jewish population. Mixed with Social Darwinism, it set the stage for the Holocaust.

Seven decades later, most Europeans can and do save themselves as they please, with many increasingly refusing the very premise of their supposed salvation. This said, a small but loud (and growing) share of European Muslims place their word above the sword of the state and it is hard to ignore current tensions between the increasingly secular societies of Europe and their respective Muslim minorities. But European affairs are increasingly devoid of relevance and the real tensions between the sword and the word exist in Asia and its sub-regions.

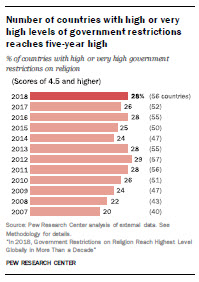

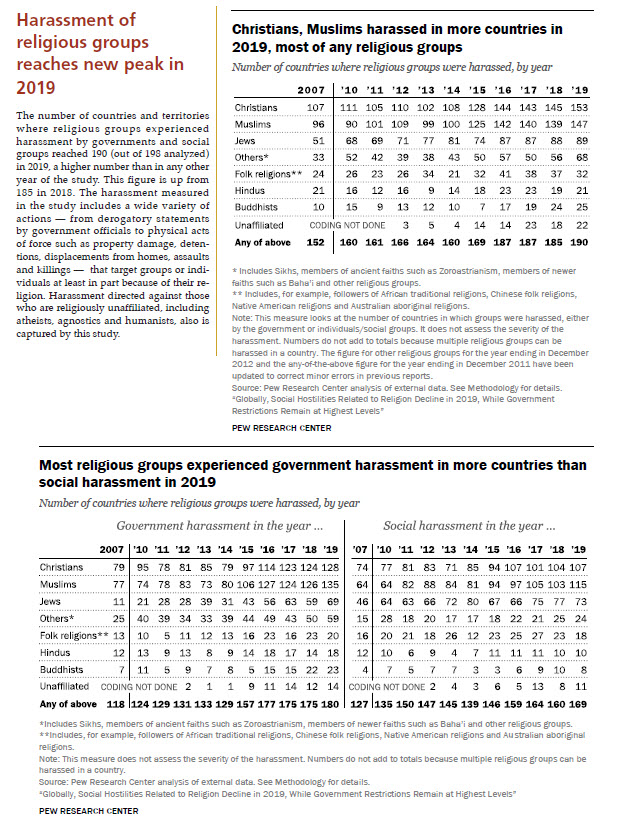

As the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Centre has shown, the suppression of religious minorities — or more broadly, religious belief — has been escalating (https://www.pewforum.org/2021/09/30/harassment-of-religious-groups-reaches-new-peak-in-2019/).

Drawing on the work of the Pew Research Centre, various governmental and non-governmental groups and international agencies, this list draws attention to states that openly oppress and even commit genocide against religious minorities. It is not a quantitative ranking, but rather a qualitative representation of the worst offenders against religious minorities specifically and the right to worship generally. As such, it aims for a measure of balance, in so far as it does not want to downplay the sufferings of some while exaggerating those of others. This said, three things stand out. First, religious persecution is part and parcel of authoritarian rule, whether it be secular, as in the case of China, or theocratic in the case of Shia Iran and its Sunni rival Saudi Arabia. Second, Asia is becoming increasingly hostile for religious minorities, Christian and otherwise. (As such, the region continues a historic tradition. While the Ottomans’ genocide of Armenian Christians during and after the First World War had causes, religion was one of them). Third, the number of Christians clinging to their homes in the Middle East continues to shrink as they are effectively driven out, and it is uncertain whether they will have a future in the region from where their religion spread into every corner of the world. Fourth, the sword and the word remain firmly wed in the Islamic world, as recently demonstrated by the behaviour of the Sunni-sect Taliban following their return to power in Afghanistan. Amnesty International has already received accounts of Taliban fighters massacring members of Afghanistan’s Shia minority for being out of line with the Taliban’s interpretation of Islam. Reports of a woman killed for not wearing a burqa (on the very day Taliban leaders pledged to protect the rights of women within the norms of Islamic law) won’t likely dispel the perception that much of the Islamic world remains a realm of religious intolerance.

China

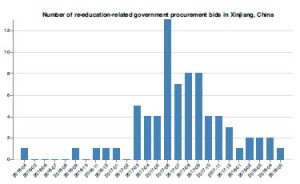

The message sent by the British House of Commons in April 2021 was symbolic, but sharp. China, so read the non-binding motion passed by parliamentarians, is committing genocide against the Uyghur people, the historic Muslim minority of Xinjiang province.

Subject to forced labour, torture and sterilization in internment camps euphemistically named “re-education” camps, one million people are currently suffering the personal consequences of living under the rule of a Communist Party that subscribes to official atheism and suspects believers of challenging its authority.

But the status of the Uyghur has not just soured already strained relations between several Western countries and China in drawing attention to the difference between religious toleration and persecution; it has also raised the provocative but legitimate question (as posed by Forbes) of whether Christians would undergo comparable treatment in the future as a growing number of Chinese turn toward, rather than away, from religion.

The Chinese state officially recognizes five religions (Buddhism, Catholicism, Daoism, Islam and Protestantism) and citizens “enjoy freedom of religion” under the Chinese constitution. But Human Rights Watch has questioned the reliability of this promise.

State officials routinely supervise registered and unregistered religious groups with the stated purpose of preventing public disorder, an agenda authorities interpret broadly and with growing animosity toward Christians, according to Christian and non-Christian groups.

While Christianity has ebbed and flowed with China’s changing political tides — Washington’s Freedom House, which conducts research on democracy, political freedom and human rights, speaks of “periodic cycles of growth and suppression” — the religion has been finding new followers across all segments of the society since the early 1980s, when the Communist Party relaxed religious rules.

Current estimates peg the total number of Protestants and Catholics at anywhere between 103 million and 127 million, with Protestants outnumbering Catholics by a large margin. Other organizations say the number is higher and that the number of Christians could reach as many as 160 million by 2025 and 247 million by 2030, according to projections from the Pew Research Centre cited by the New York-headquartered Council on Foreign Relations.

This development has not gone unnoticed among Communist authorities, who have long considered Christianity a Trojan Horse through which the West introduces unwanted ideas.

None other than President Xi Jinping is a strong subscriber to this theory. His government has declared that it will not tolerate any other source of “moral and social authority” and the campaign to “Sinicize” religion has been under way since 2015 continues.

This forced alignment of Christian faith with communist ideology has led to the closing of churches existing outside those sanctioned by the state, the arrest of preachers and parishioners who preached and prayed in them and the rewriting of Christian scriptures with pictures of Xi and Mao replacing Christian icons. An historic, albeit provisional agreement, signed in 2018 between China and the Holy See (the Vatican state and the religious entity that is the Catholic Church) governing the appointment of bishops continues into 2022. But Beijing shows indifference, even contempt toward the letter — never mind the spirit — of the agreement.

This does not bode well for relations between the world’s most populous country and the church that speaks for its largest denomination.

Ultimately, Freedom House points to a linkage between international events and state-sanctioned repression of Christianity. It spiked in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. As tensions between China and its Western rivals rise, Christians may prepare for another round of repressions if they are not already

experiencing them.

Myanmar (Burma)

As this country of 57 million and multiple ethnic groups continues its descent into civil war following yet another military coup in early 2021, attention has faded from the fate of the Rohingya, the increasingly smaller Muslim minority in the largely Buddhist country. Since August 2017, more than 742,000 have officially fled Myanmar for neighbouring Bangladesh, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). There, they live in unbearable conditions, uncertain about their future, as authorities do not recognize them as a “national race,” having stripped them of citizenship in 1982.

More than one millon Rohingya have fled the country since the early 1990s. Another 130,000 of 600,000 remaining Rohingya live in government-run detention camps.

“The squalid and oppressive conditions imposed on the Rohingya amount to the crimes against humanity of persecution, apartheid and severe deprivation of liberty,” Human Rights Watch concludes.

Yet Myanmar is neither close to a restoration of civilian rule nor the legal punishment of those responsible for the actions in 2017 that amounted to a genocide, as defined by the United Nations, even as a case before the International Court of Justice unfolds.

The plight of the Rohingya briefly grabbed the world’s attention again in March 2021, when a deadly fire killing at least 15 people and displacing tens of thousands swept through Cox’s Bazar Refugee Camp, which is sheltering the world’s largest number — 600,000 in total — of refugees, according to UNHCR.

But such temporary flickers of concern compete against decades of indifference for the Rohingya, whose faith and supposed foreignness have made them easy targets for persecution for decades.

As the CIA notes in its World Fact Book assessment, the Rohingya, “arguably the most persecuted population in the country,” form a “patchwork” of more than 130 religious and ethnic groups.

“The Burmese government and the Buddhist majority see the Rohingya as a threat to identity, competitors for jobs and resources, terrorists,” says the CIA, “and some still resent them for their alliance with Burma’s British colonizers during the 19th Century.”

This points to one of the peculiarities of Myanmar. As Foreign Policy notes, Buddhist movements in Asia have often shown “few qualms” about the use of force against perceived enemies of the faith and about stoking nationalism.

Radical Buddhist monks helped to spark the recent wave of persecution in August 2017 and such prominent monks as Sitagu Sayadaw have collaborated with the generals during the recent uprising. This said, others have broken with the generals.

The fate of the Rohingya points to a larger problem in Myanmar: the lack of tolerance for non-Buddhist faiths and the willingness of authorities to do the bidding of religious zealots. Even Aung San Suu Kyi, the once-revered patron saint of democracy in Myanmar, now back under house arrest, could not risk alienating them, as evidenced by her refusal to denounce the violence against the Rohingya, never mind stop it.

Myanmar’s Christians (6.2 per cent of the population) have also started to experience what the Rohingya people have felt for decades. As The Wall Street Journal and other sources have reported, the country’s military has also systematically targeted Christians, who, by virtue of the religion’s popularity among the Kachin, Karen and Shan ethnic minorities, find themselves greatly outnumbered by the ethnic Burmese who account for 68 per cent of the population.

The Maldives

After Mohamed Rusthum Mujuthaba had received death threats for his social media posts, he did what any reasonable person might do: he asked for police protection. But instead of protecting Rusthum, police arrested him on charges of blasphemy against Islam, that country’s state religion. Nearly two years after his arrest in September 2019, Rusthum remains in pre-trial detention, where he has suffered torture and solitary confinement, according to his family, as the International Humanist and Ethical Union reported in testimony during the 46th session of the UN Human Rights Council.

Rusthum’s case is hardly unique, as he is among six Maldivians accused of blasphemy since the current government of Ibrahim Mohamed Solih assumed power in November 2018, according to the International Humanist and Ethical Union, founded in the Netherlands and headquartered in London. Solih is representative of the larger threats facing those calling for more freedom of religion and speech in Maldivian society.

Prominent blogger Yameen Rasheed was found dead of stab wounds in the stairway of his apartment complex in the early morning hours of April 23, 2017. Like Rusthum, Rasheed had also asked for police protection, but authorities ignored his plea. They later arrested and tried six individuals linked to a radical mosque. But more than four years later, the trial has dragged on, with Rasheed’s family and Amnesty International complaining of delays in the administration of justice.

Rasheed’s death (with its eerie similarities to the murder of Russian activist Anna Politkovskaya, who was also found dead outside of her apartment after exposing corruption) made international headlines. It drew attention to a long list of other individuals — be they journalists such as Ahmed Rilwan or lawmakers such as Afrasheem Ali — who have died at the hands of Islamic radicals, who find themselves tolerated, if not encouraged, by a state-sanctioned climate of religious intimidation and intolerance.

The constitution of the Maldives declares Islam to be the state religion and denies citizenship to non-Muslims. All candidates for elected offices must be followers of Sunni Islam, explicitly excluding adherents of minority religions, according to Freedom House. The latter laments the growing influence of Islamists on the education system and other spheres of society, an influence that leaves no room for public expressions of non-Islamic faith. The constitution guarantees freedom of expression, but only if exercised in a manner that is “not contrary to any tenet of Islam,” which Freedom House describes as a vague condition that encourages self-censorship in the media. The media stand accused by the International Humanist and Ethical Union of spotlighting individuals with allegations of apostasy, atheism, secularism, homosexuality or support for homosexuality.

International observers have praised the current government for launching the Commission on Investigation of Murders and Enforced Disappearances, which is designed to investigate cases such as Rasheed’s. But its slow progress contrasts with years of growing religious extremism, stoked in part by the previous administration, and confirms the unholy confluence of political corruption and religious fervour in a place best known for pristine beaches.

Iran

Lost in the current climate of geopolitical tension and clandestine warfare between Iran and Israel is the historic role that Iran played in saving thousands of Polish Jews fleeing the German-orchestrated Holocaust during the Second World War. A total of 116,000 Polish refugees, including 5,000 to 6,000 Jews, many of them orphaned children, used Iran, itself struggling with famine and political impotency, as a temporary refuge, then a transit point between 1942 and 1945, mainly to British overseas colonies and protectorates.

This history, recently told in personal detail by Mikhal Dekel in Tehran Children, draws attention to the deep, biblical ties that connect Judaism to Iran and its historic predecessors, with Jews having lived on the current territory of Iran for 2,700 years.

Even today, as leading Iranian officials continue to threaten Israel with another Holocaust while denying the first one, 8,300 Jews (as of 2019) continue to live in Iran, which holds the distinction of being home to the largest Jewish population in the Middle East outside Israel.

But their numbers are dwindling. At least 80,000 Jews lived in Iran before the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Tens of thousands have, since then, left Iran in the face of state-sponsored persecution. Those who remain have faced spurious charges of being spies for Israel as well as violent forms of harassment and intimidation, as catalogued by governmental and non-governmental observers. Within this context, the Iranian state frequently riles up the masses with anti-Semitic rhetoric.

The current Iranian constitution recognizes Jews along with Zoroastrians and certain Christian communities as non-Muslim religious minorities. These small groups are relatively free to worship, according to Freedom House, a perspective also heard from religious leaders in Iran itself. The Iranian parliament also reserves five seats for the recognized non-Muslim minority groups: Jews, Armenian Christians, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians and Zoroastrians.

But such forms of institutional recognition in a legislature denied any genuine authority should not distract from the fact that religious minorities such as Jews find themselves living in a constant state of anxiety, never sure how or when the mullahs might limit religious freedom.

Sadly, Jews in Iran can count themselves among the more privileged religious minorities.

Consider the members of the Baha’i faith, whose followers are, in the words of Freedom House, systematically persecuted, sentenced to prison and banned from access to higher education.

The hostility of the mullahs toward religious minorities does not stop even at fellow Muslims, as Sunni Muslims also find themselves excluded from positions and denied opportunities to worship. In a way, this treatment of Sunni Muslims at home reflects the sectarian crack running through the Muslim world at large.

Syria

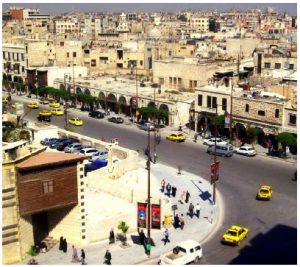

While some believe that Islamic State has been vanquished, many think it is still an entity that will regroup. Nevertheless, in the short-term, at least, defeat and destruction of the Islamic State may have freed the religious minorities of Syria from an existentialist threat, but their long-term future looks perilous, because the country — once a relative beacon of religious pluralism — has become more sectarian.

Ten years after the start of the civil war in Syria, hundreds of thousands lie buried in its soil, killed by the weapons of their own government or those of foreign powers supporting the various factions.

Millions more have fled their homes. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the war has chased more than half of the overall population (about 13.5 million) from their homes, displacing them to other parts of Syria or abroad. At total of 6.7 million Syrian refugees have sought refuge in 128 countries, with Turkey hosting 3.6 million, which is more than half of Syria’s refugees. As the years pass, it is less and less likely many will return, depriving the country of human potential and resources. Those who have remained live among the ruins of destroyed cities and devastated institutions of every kind. And yet this state of sorrow and suffering has served Syrian President Bashar al-Assad well.

When it became increasingly clear that none of the rebel groups opposing al-Assad could push him from power, thanks to support from Russia and Iran, he started to spell out his vision for a “healthier and more homogenous society in the true sense,” code for a country less diverse and presumably easier to control, a vision increasingly appearing before the eyes of the world.

As in the rest of the Middle East (minus Iran and Iraq) and the Islamic world at large, Muslims of the Sunni sect have historically dominated the religious demography of Syria, with 74 per cent. But their numbers are smaller relative to other parts of the region, having to co-exist with smaller groups like the Druze, Yazidis, Christians and Alawites, a Shia Muslim sect.

This last group, from which the al-Assad family hails, has historically sought to maintain its ruling status in Syrian society by stressing secular pan-Arabic nationalism and stifling, sometimes by brutal force, any signs of sectarianism by the Sunni majority. Yet it was al-Assad who stoked sectarian violence by reframing the political rebellion against him as a sectarian conflict.

Freedom House notes that this choice saw the regime discredit the rebellion during its early stages through the release of jihadists. This move, reported widely by Western media such as the Atlantic, gave the regime licence to suppress Sunnis, who bore the brunt of repression, according to Freedom House.

Even the temporary occupation of Syrian territory by Islamic State, borne out of weakness by al-Assad’s regime, served his sectarian agenda because he could present himself to the Western world, including the United States, as the defender of religious minorities, including Christians, in the face of ISIS’s undeniable barbarism against them and other religious minorities.

True, al-Assad’s coalition included Christians with sympathies for him, but this alliance has always appeared fraught with ambivalences, if not illusionary.

Ultimately, Syrian Christians have done exactly what the smaller minority of Yazidis have done — fled, if possible, the chaos that al-Assad has unleashed.

Before the outbreak of the war, Christians accounted for 10 per cent (about one million) of the Syrian population. A decade later, they account for 5 per cent, many of them having fled the country to avoid service in al-Assad’s military or to escape radical Sunni Islamists opposed to the regime.

Those who remain now find themselves in a double-bind. They remain objects of suspicion by a murderous regime, cynical and capable of committing atrocities against its own people. At the same time, they live in a ruined state that is poisoned by sectarianism with severe consequences for all.

Iraq

When Pope Francis visited Mosul in March, he prayed for the war victims of the Middle East. During this historic trip as the first pope to ever visit Iraq, he was walking the Earth mere kilometres away from what many believe to be the Tomb of Jonah, the Bible’s uneasy prophet, whom God had sent to the Assyrian city of Nineveh to prophesy its doom unless its residents repented their wickedness.

Nineveh’s modern-day successor, Mosul, was — to use the words of Jonah himself — a place where “the wickedness of men rose up to heaven” after forces of the Islamic State had captured it in June 2014 as they spread across parts of Iraq and Syria.

Their seizure of Iraq’s second-largest city sparked a modern-day exodus of Christians from Mosul and the nearby cities of the Nineveh Plain, such as Qaraqosh, the largest city of Iraq’s Christian heartland.

What followed was the desecration and destruction of ancient Christian churches and religious symbols, theft and extortion and forced conversion on pain of death.

For the first time in nearly two millenniums, church bells fell silent for years in one of the oldest regions of Christendom, sparking the question of whether the world was witnessing the end of Christianity in the Middle East.

Christians, of course, did not share this fate alone, as Islamic State forces also persecuted Yazidis and other Muslims who did not conform to its radical interpretation of Islam.

Deeply moved by the physical and spiritual damage that Islamic State had caused during its three-year-long occupation of Mosul before Kurdish and Iraqi government forces expelled it, Pope Francis referenced this shared suffering.

“How cruel it is that this country, the cradle of civilization, should have been afflicted by so barbarous a blow, with ancient places of worship destroyed,” the Pope told The New York Times. Thousands of Muslims, Christians and Yazidis, he said, “were cruelly annihilated by terrorism, and others forcibly displaced or killed.”

With these words, the Pope drew

attention to the religious diversity in the region, a diversity that ultimately depends on the steadfastness of religious minorities such as Christians and a broader commitment to religious pluralism by a state with barely existing institutions and rife with sectarianism.

Accordingly, the Pope called on Christians to forgive their trespassers and rebuild, while praising their perseverance. But the Pope’s appeal to persist is falling on fewer and fewer ears.

When he toured the historic ruin of Ur, believed to be the birthplace of Abraham, the personified root of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, he visited a region nearly emptied of Christians, with only one Christian family said to be left in the nearby provincial capital of Nasiriya, according to The New York Times.

While Christians had experienced decades of discrimination before the 2003 invasion of Iraq by U.S.-led forces, their fate worsened after it as the country descended into violence and civil war, eventually getting caught in the maelstrom of the Syrian civil war. Within this context, Sunni and Shia extremists treated local Christians (their roots in the region dating back to late Antiquity) as fifth columnists for Western forces with predictable results. They include the destruction of churches and the threat of death unless they convert, pay a tax or leave the area.

As in neighbouring Syria and Iran, all part of the Shia Crescent, the number of Christians in Iraq has declined precipitously. According to U.S. estimates, Iraq’s overall Christian population has decreased at least 50 per cent and perhaps as much as 90 per cent since 2003, with many fleeing to Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and beyond.

Only time will tell whether the Pope’s visit will reverse current trajectories. But his sermon in Mosul included a promising reminder when he noted that the inhabitants of Nineveh eventually heeded the words of Jonah.

Malaysia

A self-described born-again Muslim, Mustafa Akyol sees Islam going through a crisis that threatens the very future of Islamic societies, even Islam itself, unless the religion undergoes an Enlightenment that divorces the sword from the word.

A self-described born-again Muslim, Mustafa Akyol sees Islam going through a crisis that threatens the very future of Islamic societies, even Islam itself, unless the religion undergoes an Enlightenment that divorces the sword from the word.

Islam, writes the author of Reopening Muslim Minds: A Return to Reason, Freedom, and Tolerance, must save itself from its contemporary marriage with coercive power.

Akyol, a Cato Institute fellow, experienced this marriage firsthand when he visited Malaysia in late September 2017 to make his long-running case, through a series of lectures, for a reformed Islam, the second of which called on Muslims to uphold freedom of conscience in line with the Qur’anic dictum against compulsion in religion.

“I said that apostasy should not be punished by death, as it is in Saudi Arabia, or with ‘rehabilitation,’ as it is in Malaysia,” he wrote. This appeal earned him a visit from authorities at the end of his lecture, an overnight stay in prison and an appearance before a Sharia court, where authorities interrogated him for hours before releasing him.

“This incident,” he wrote in The New York Times, “showed me once again that there is a major problem in Islam today: a passion to impose religion, rather than merely proposing it, a mindset that most Christians left behind at the time of the Inquisition.”

Unfortunately, this attitude appears to be flourishing in Malaysia (along with neighbouring Indonesia).

As the Council on Foreign Relations notes, the two countries have “witnessed an upswing in harder-line Islamist sentiment,” which further enforces an artificial form of religious apartheid that denies personal agency and obscures the country’s religious diversity. By way of background, Muslims account for 61.3 of the population; Buddhists, 19.8 per cent; Christians, 9.2 per cent; Hindus, 6.3 per cent; while followers of Confucianism, Taoism and other traditional Chinese religions account for 1.3 per cent.

Of interest and influence, Freedom House notes, is the role of the powerful Malaysian Islamic Development Department (JAKIM) in shaping and enforcing the practice of Islam in Malaysia. Local state officials also have considerable influence.

While the constitution enshrines freedom of worship, it declares Islam as the country’s official religion and automatically defines all ethnic Malays as Muslims. In other words, the government sees faith as a product of biology (rather than social conditioning), a logic designed to discourage conversion.

While conversion to a non-Muslim religion is possible, would-be converts face immense hurdles. Specifically, they have to make their case to a religious court and cases of conversion are incredibly rare. Those who signal their desire to convert face the possibility of being placed in rehabilitation centres, a prospect that forces many to live double lives, ripping apart families along the way. Other cases have seen parents secretly convert their children to Islam to gain the upper hand in custody battles.

As Freedom House says, Muslim children (along with civil servants) are required to receive religious education using government-approved curriculums and instructors.

Muslims are subject to Sharia (Islamic law) and the constitution stipulates that all matters related to Islam should be heard in Sharia courts. This means Muslims and non-Muslims receive different treatment in “moral” and family law cases, with non-Muslims subject to English common law.

Freedom House also notes that the state prohibits the practice of Islam other than the Sunni version. Shiites and other sects face discrimination. Further, it notes, non-Muslims are not able to build houses of worship as easily as Muslims, and the state retains the right to demolish unregistered religious statues and houses of worship.

These restrictions have economic consequences. Ethnic Chinese, who account for just under 21 per cent of the population, are increasingly leaving the country, taking with them their money and education.

Akyol’s prediction is slowly, but steadily coming true.

Algeria

Like so many places in the Middle East, Algeria breathes the spirit of ancient Christendom.

Within the borders of the modern-day Annaba, near the border with Tunisia, lie the ruins of Hippo, where St. Augustine served as bishop during the final phase of the Roman Empire. Having converted from paganism, St. Augustine’s influence on Christendom has remained inexorable. His views on sin, grace, freedom and sexuality have shaped Catholicism specifically and Western culture generally, deep into the 19th Century and beyond, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says, if only as a foil for contemporary liberals, feminists and secularists.

If St. Augustine’s philosophy has survived into the present, history has reduced his work and that of other early Christians living and praying in North Africa to little more than archeological attractions.

Like its neighbours, Africa’s largest country by area is an overwhelmingly Islamic country, as Muslims account for 98 to 99 per cent of the population.

And yet in what can only be read as a sign of weakness, the Algerian government treats the few religious minorities (Jews, Christians, as well as Ahmadiyya and Shia Muslims) as threats that must not be allowed to “shake the faith of Muslims,” to use the language of the ban on proselytizing by non-Muslims.

Violators (as deemed by authorities) face a significant fine and a prison sentence of up five years for printing, storing or distributing materials intended to convert Muslims.

Authorities, for example, recently arrested Christians for violating said ban, as reported by Pew Research.

Such actions confirm Algeria’s history of repressing and persecuting religious minorities and contradict previous constitutional commitments to conscience and worship as found in the 2016 constitution.

Algerian authorities have since dropped such pretence by eliminating the language from the 2020 constitution that protects “freedom of conscience” following a constitutional reform of questionable legitimacy, based on low turnout and the absence of genuine consultation with all groups, including the 130,000 to 200,000 Christians in a country of 43 million.

Religious minorities are already fearful that authorities will use the constitution to further erode their numbers, even if, as Human Rights Watch suggests, the new constitution promises the right to “practise a religion,” a promise devoid of credibility.

Central to Algeria’s apparatus of religious control is the ministry of religious affairs, an Orwellian phrase if one ever existed. Groups must register with it before conducting any activities, and a commission under the ministry’s supervision approves worship locations. There is only one catch. The commission rarely approves locations — some sources claim it has never met — leaving non-Muslim worshippers in violation of the law. Claiming merely to enforce the law, authorities can close places of worship used by Christians or the non-Sunni Muslims such as the 2,000-member-strong Ahmadi community, a Muslim sect long the object of government persecution.

Saudi Arabia

The diplomatic quarter of Riyadh or Neom is a futuristic mega-city 33 times the size of New York City that is currently under construction in the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia bordering the Red Sea.

It is the potential, highly speculative location of what would be that country’s first church, should authorities ever permit such a place of Christian worship in the country that sees itself as the self-described defender of Muslims around the world. Some (like an unnamed royal adviser quoted in The Economist) say it is not a question of if, but when the country, home to the two holiest cities in Islam — Mecca and Medina, the respective birth and burial place of the Prophet Muhammad — would sanction such a step.

This prediction has its premise in the past actions of Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS), the de-facto ruler of Saudi Arabia.

Since coming to power in 2017, MBS has met with Maronite Patriarch Bechara Boutros al-Rai, who represents Christians in Lebanon, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby and Coptic Pope Tawadros II. MBS himself has spoken of religious tolerance, acknowledged the historic presence of Christians on the Arabian Peninsula and held several meetings with evangelical Christians from the United States who are eager to open the first church. King Salman has met French Catholic Cardinal Jean-Louis Pierre (since deceased) and Pope Francis himself visited the neighbouring United Arab Emirates (a Saudi ally) in early February 2019 as the first pontiff to travel to the Arabian Peninsula.

These Saudi overtures to the Christian world and its various emissaries have unfolded against the backdrop of larger reforms designed to make Saudi Arabia more attractive to foreign investors as the country designs a post-oil future.

But Western ears have heard such promises before, only to see them go unfulfilled.

True, MBS has cut the influence of Saudi Arabia’s religious police — the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice — and radical clerics at large.

But their current weariness and suspicion about MBS could easily turn into something more threatening if he were to allow a church.

Christians living in Saudi Arabia, some 1.2 million in a country of 34 million, most of them working migrants from Asia and Africa, may no longer suffer the worst effects of the Saudi state, but their religion remains underground. Open displays of faith are to be avoided lest believers want to invite danger. Even Evangelical Christians from the United States, who enjoy the support of former U.S. president Donald Trump, an ally of MBS, had to heed this lesson. Ultimately, MBS has skilfully exploited low expectations of himself and any assessment of his regime boils down to the following: Is he pursuing genuine reform or is he guilty of window dressing? MBS’s proven involvement in the brutal murder of regime critics, such as journalist Jamal Khashoggi, is one of a long litany of human rights abuses against critics at home.

Russia

Harassment, video surveillance, arrest threats, torture and long prison terms: According to The Guardian and other observers such as Human Rights Watch, these are the realities facing the 175,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses living in Russia.

Relative to the overall population of 142.3 million, this Christian sect makes up only a fraction, yet the state of Vladimir Putin places them in the same category as neo-Nazis and members of al-Qaeda.

Jehovah’s Witnesses earned the unjustified wrath of the state after an April 2017 ruling by the Russian Supreme Court, which declared the church’s head office an extremist organization and banned 395 branches across Russia.

As of mid-June 2021, Russian officials had investigated 418 members of the church, with 53 Witnesses in pre-trial detention or sentenced to prison, another 36 under house arrest and 224 not allowed to leave their hometown, according to JW.org.

UN observers have found these detentions to be arbitrary, lacking legal basis and in violation of the right to freedom of religion, while other groups such as Human Rights Watch have called on the Russian government to reverse course.

In typical manner, Putin first treated the accusations with feigned ignorance, even concern for the Jehovah’s Witnesses before signalling his tacit approval of them in December 2018. Since then, persecution of this Christian minority has only intensified, likely to the satisfaction of the Russian Orthodox Church. It supports the ban, saying it would combat the “spread of cultist ideas, which have nothing in common with Christian religion,” as cited by Pew Research. This language echoes the words of Putin himself, who has described Jehovah’s Witnesses as people who practise faiths that are not “traditional” in Russia.

This overlap points to a larger pattern: the alignment of the Russian state with the agenda of the Russian Orthodox Church, currently headed by Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, now in office for more than a decade.

As Russian historian Michael Khodarkovsky has noted in The New York Times, this relationship is as old as Russia itself, with the church playing the role of subservient proponent of a political theology that presents Moscow as the Second Jerusalem and the Third Rome (after Rome and Constantinople).

True, seven decades of state-enforced atheism during the Soviet period have shown their effects on Russia’s religious sociology. Russian society is thoroughly secular as Russian Orthodox Christians — the largest sectarian group — account for somewhere between 15 and 20 per cent of the population, not far ahead of Muslims, who account for 10 to 15 per cent, followed by other Christians at 2 per cent.

Yet the Russian Orthodox Church enjoys a privileged position in Russia, “working closely with the government on foreign and domestic policy priorities,” as Freedom House notes. Kirill himself said that even during the Russian Empire, “the church did not have an equal partner in the face of government.”

More broadly, the vague, increasingly harsher extremist legislation sweeping up Jehovah’s Witnesses has in the past also netted other believers and non-believers appearing as threats to the state-church alliance propping up Putin’s regime, its most recent catch being Alexei Navalny’s nationwide political organization.

It, like Jehovah’s Witnesses, has since suspended operations to avoid a similar fate. That will likely not help.

(https://www.pewforum.org/2021/09/30/harassment-of-religious-groups-reaches-new-peak-in-2019/)

Wolfgang Depner is a writer who lives in Greater Victoria in British Columbia, where he teaches at Royal Roads University. He has previously taught international politics and political philosophy at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus.