By Khaled Bahah

Ambassador of Yemen

Yemen, an Arab country and one of the oldest centres of civilization, presides over one of the busiest and most crucial shipping routes in the world. Bordered by Saudi Arabia, the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Gulf of Aden and Oman, it comprises more than 555,000 square kilometres with some 2,000 kilometres of coast and in excess of 200 islands (including the famous natural paradise of Socotra). Yemen’s population is approximately 24 million, with a growth rate of 3.4 percent and a GDP per capita of US$1,118.

Prior to 1990, there were two Yemens — the northern Yemen Arab Republic, having attained Independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1918, and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, which had been under British rule from 1839-1967. On May 22, 1990, a united Yemen was formed and northern President Ali Abdullah Saleh became president of the new Republic of Yemen. However, the fusion of two countries with incompatible systems led to a bitter civil war in 1994. The South was defeated on July 7 of that year – a resentment that still lingers.

Sadly, true democracy eluded the people of Yemen under Saleh. A cunning political survivor, he structured an impenetrable power base of nepotism, placing his sons, brothers and nephews, along with members of his inner circle, in control of the main military and security forces. His outer circle encompassed the tribal and religious elite, with influence extending to key political and commercial stakeholders. His oppressive regime exploited Yemen’s resources and people for a staggering 33 years.

In recent years, rumblings of discontent mounted against Saleh, with a strengthening of opposition parties, primarily the Joint Meeting Parties — a coalition which includes the southern Socialist Party and the powerful but fragmented northern Islah Party.

Tribal unrest is led by the Al Ahmar family of the powerful Hashid tribe, from which Saleh hails. Though they were allies of Saleh under the late Abdullah Al Ahmar, his son Hamid opposes the president and has been joined by several brothers who resigned from the Saleh regime.

Since 2004, the northern Houthis have led a rebellion against the government. Their grievances include religious and economic marginalization concerns; while in the south, an independence movement has intensified since 2007 due to the regime’s northern bias and discrimination.

Yemen has also been a victim of terrorism since the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole in Aden Harbour. While the U.S. considers Saleh an ally in the fight against terrorism, many Yemenis argue that he collaborates with al-Qaeda when it is advantageous to him. The chaos of 2011 has served to strengthen al-Qaeda’s presence in isolated southern pockets.

Saleh, a former military man with negligible education, is the most Machiavellian of Arab autocrats. Throughout his rule, he has been a capricious man of broken promises — justifying his erratic behaviour by likening the ruling of Yemen to “dancing on the heads of snakes.” However, a Tunisian fruit-seller’s suicide began the chain of events that brought Saleh’s dancing to an end.

Given such disenchantment with the regime, Yemen has been a vigorous participant in the contagious revolution known as the Arab Spring, which has mesmerized the world, altering the destiny of millions.

Rioting broke out in mid-January, 2011, signifying the start of Yemen’s revolution. Demonstrators were critical of the president and demanded change. Violent crackdowns by security forces ensued. However, unlike former insurgencies, Yemenis refused to be silenced, and their numbers grew. The revolution was initiated by the determined courage of youth to fight for a better life, using the information highway as a pivotal tool to organize protest and create real-time witnesses all over the world. But ultimate change evolved through the heroic struggles of all Yemenis — standing united, demanding liberation.

Prior to January, Saleh had proposed constitutional amendments, relinquishing both his right to be president in perpetuity and the inferred inheritance of the title by his son. Once rioting broke out, he chose to withdraw these proposals. When this had no effect to bring calm, the regime manufactured pro-Saleh demonstrations outside the presidential palace. However, the demand for Saleh’s resignation continued, joined by many tribal people.

Tragedy struck March 18, as troops massacred more than 56 civilians in Change Square, Sana’a. A state of emergency was declared, and the following day, nine Yemeni ambassadors, including myself in Ottawa, wrote to the president condemning the massacres. International outrage was sparked, and by March 23, Brigadier Ali Mohsen al Ahmar declared support for the revolution, representing a serious high-level military rupture, while several Yemeni governorates split from government control.

In response to increasing violence, Yemen’s Foreign Minister Abubakr Al-Qirbi was dispatched to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), to hint that Saleh would sign an initiative outlining a roadmap to peaceful resolution, including power transfer, conditional upon immunity from prosecution. The GCC acted accordingly but, despite four promises to endorse the initiative, he reneged on his own proposal. The document remained unsigned and Yemen deteriorated.

On May 23, AQAP (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula) members supporting Sharia law occupied the southern coastal town of Zinjibar, killing several people. Additional fighting occurred between the regime and defectors from military troops. Conflict broke out between Republican Guard Troops, under Saleh’s son, and the Hashid tribe led by Sadiq Al-Ahmar, as military forces massacred peaceful demonstrators elsewhere.

The conflict motivated an assassination attempt at the presidential palace June 3. Several of Saleh’s entourage were killed and the president himself, despite denials, sustained serious wounds including a collapsed lung and burns to his entire body. The following day, he flew to Saudi Arabia for emergency treatment. Vice President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi became acting president by default. On July 7, the anniversary of the Black Day of Southern Defeat in the 1994 Civil War, a frail and bandaged Saleh gave a confrontational speech from Saudi Arabia, vowing revenge and threatening to “confront challenge with challenge.”

By mid-August, a National Transition Council was declared, consisting of 143 opposition members. However, roughly 20 from the south withdrew, citing unfair representation and lack of emphasis on southern issues. The massacres continued in September by the Republican Guard, led by Saleh’s son and by the central forces of his nephew, Yahya.

Abruptly, on Sept. 23, Saleh returned to Yemen. The violence escalated and UN Security Council Resolution 2014 was issued in October, expressing grave concern over the bloodshed and calling for an immediate adoption of the GCC Initiative to end the crisis. Amid the chaos, the winners of the Nobel Peace Prize were announced on Oct. 7. Among them was Yemeni female activist Tawakkul Karman, whose non-violent protest garnered her international acclaim. In accepting this honour, she dedicated it to the people of Yemen.

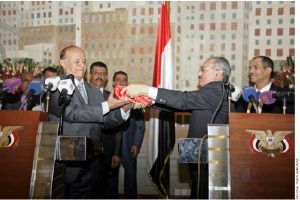

Following an absurd number of promises and subsequent refusals, Saleh finally signed the GCC Initiative Nov. 23. Much credit is due to the herculean persistence and patience of Jamal Benomar, UN envoy to Yemen, and Secretary General Al Ziani of the GCC, in implementing the initiative and putting the Operational Mechanism in place. Accordingly, on Dec. 7, a coalition of current and opposition parties, known as the National Reconciliation Government, was established and interim elections were confirmed for February 2012.

January 2012 signified the end of unrestrained revolution and the beginning of inner transformation — the objective was to establish an environment of security, unity and reform prior to multi-party elections in 2014. This process began Feb. 21 with the people formally electing to remove Saleh and appoint acting vice-president Hadi as transitional president for two years. Saleh’s agreement to relinquish power was attained upon the condition of his full immunity from prosecution. While immunity continues to be a sore point for Yemenis, it was the only means to an end. In Northern Yemen, voter turnout was significant and the election was peaceful. The south called for rejection of the election and, as a result, voter turnout was low, consisting almost entirely of northern troops stationed there. Although this underscores the massive efforts required to create future cooperation and trust, it’s important to note that only a few months ago, it would have been inconceivable that on Feb. 25, 2012, a new president would be sworn in after 33 years, seven months and four days of oppression. Equally remarkable, on Feb. 27, the first presidential ceremony in Yemen’s history was held, attended by the new leader and the former president, whose presence, strategically orchestrated by loyalists, was fiercely unappreciated by the prime minister, opposition parties and youth.

As the Operational Mechanism stipulates, President Hadi and the new coalition government will create a military committee to restore legitimate security forces. They will also form a dialogue committee, comprised of members of political parties, civil society, southern movements, tribal members, Al Houthi and youth, among others. Based on their discussions, a constitutional committee will draft a new constitution and prepare the country for authentic democratic parliamentary and presidential elections in 2013 and 2014.

Yemen’s problems are largely systemic, emanating from a leader who played the rifts within the country as a political chess game. However, though Saleh may be gone, his ghost remains through the continued presence of military control by his family and former allies such as General Ali Mosen al Ahmar and the backward tribal contingent still loyal to the late Abdulla al Ahmar. It is essential that these individuals relinquish their power immediately or they will find themselves the new target of the revolution. They must step aside in order to show the people that they are part of the cure rather than symptoms of the disease.

Yemen is a work in progress, but its victory over oppression has inspired a spirit of optimism not felt for more than three decades. While much remains to be done, genuine hope springs that on the horizon, a brilliant new sunrise is about to shine over Yemen.

Khaled Bahah is Yemen’s ambassador to Canada.